Digestive symbioses recycle plant material.

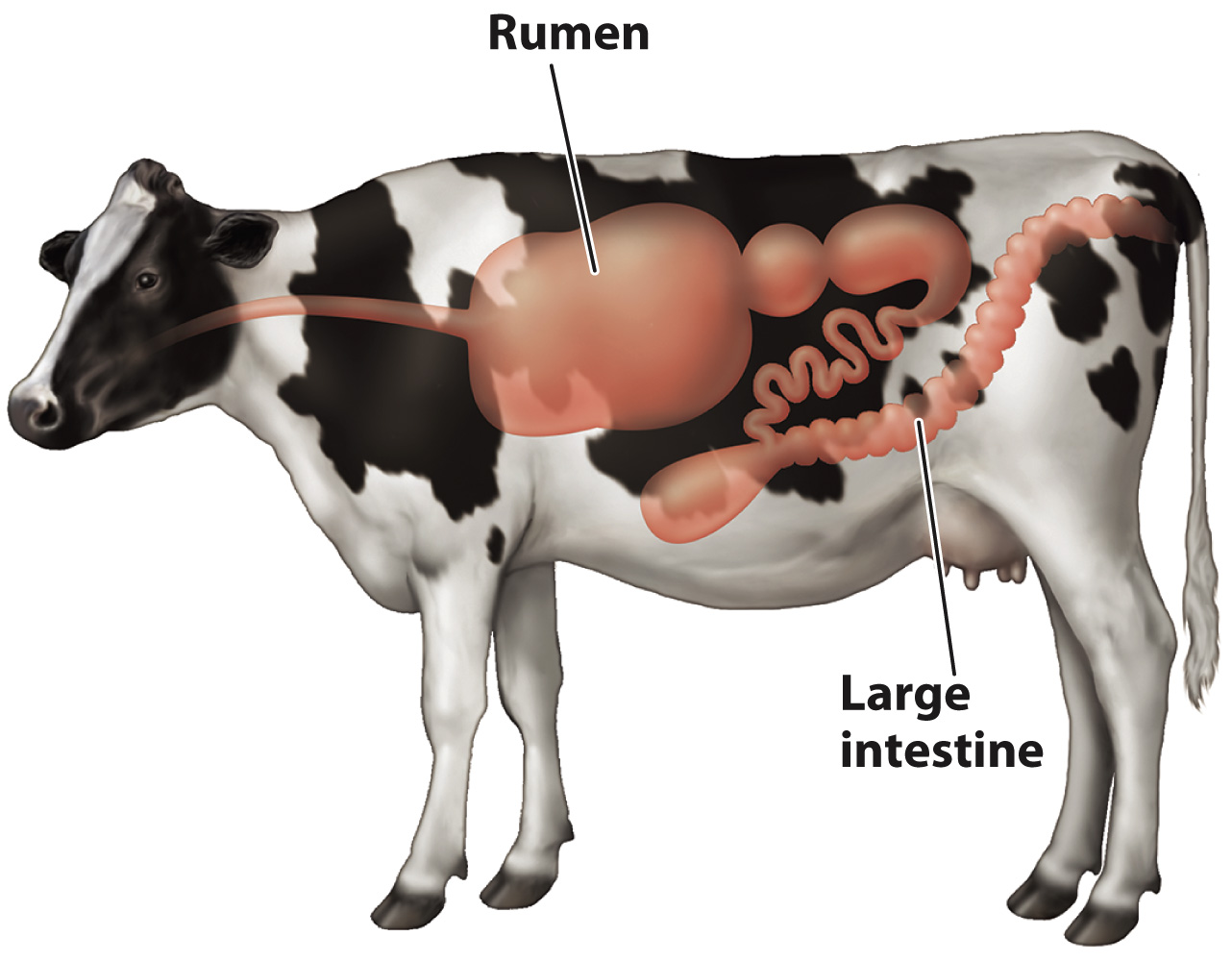

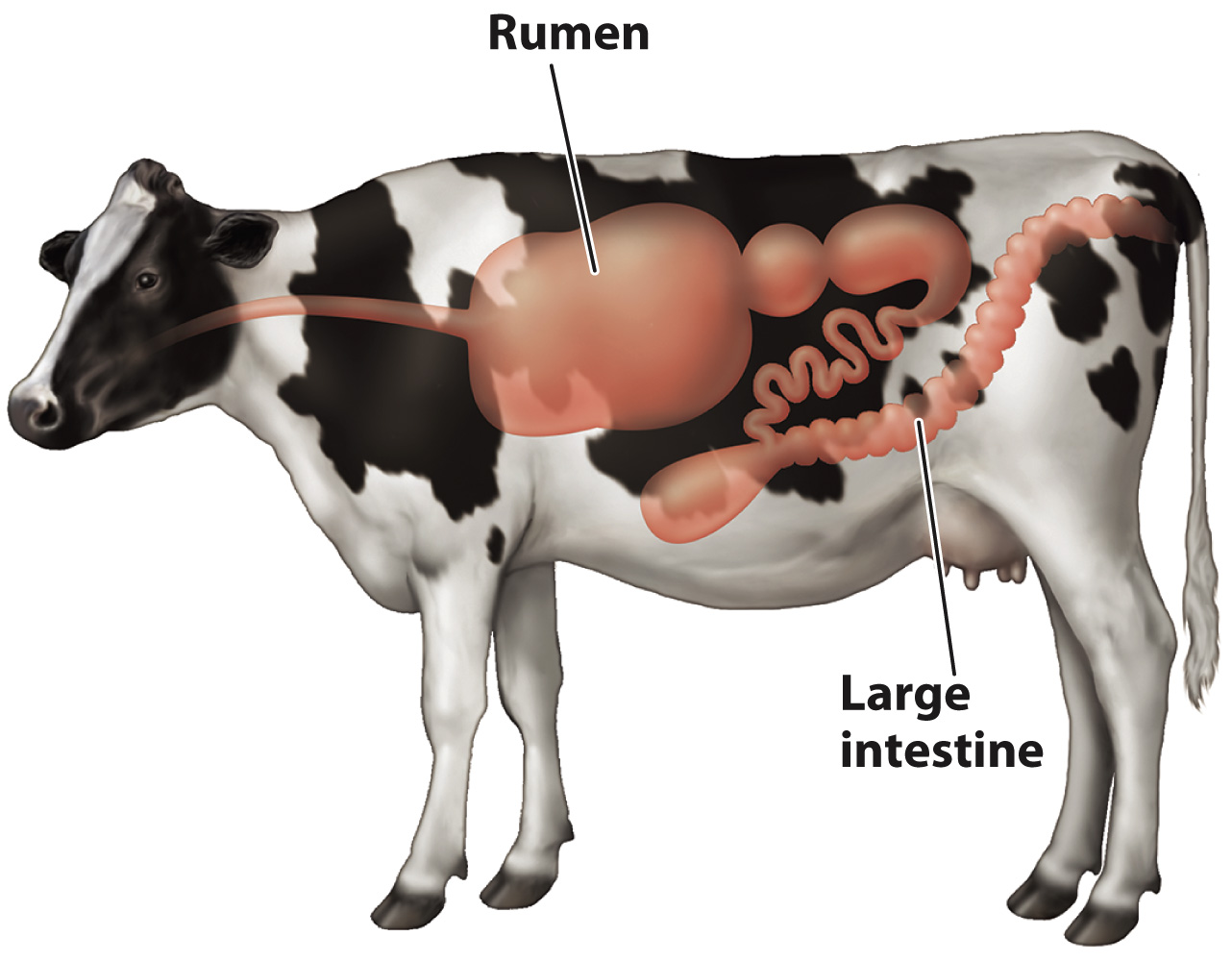

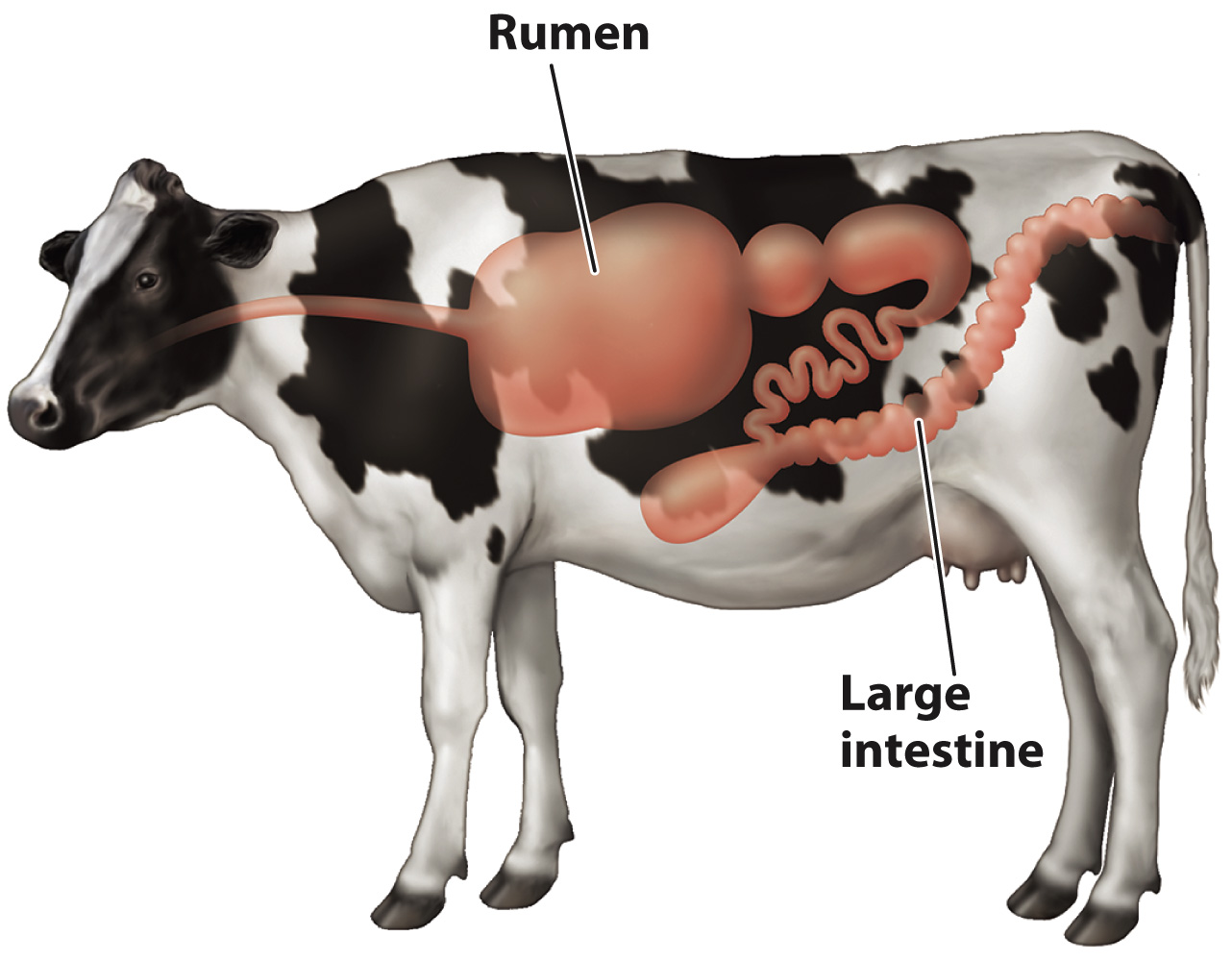

In Case 5: The Human Microbiome, we saw that diverse microorganisms in our digestive tract provide important services to our own well-being. Humans aren’t alone in hosting microbial symbionts; in fact, most animals have microbiomes. All herbivorous animals studied to date, from cows and sheep to ants, beetles, and termites, can feed on plant tissues only with the help of microbial symbionts. Much of Earth’s biomass consists of wood and other plant tissues rich in cellulose and lignin. Few organisms have the ability to digest these molecules, but some microorganisms, mainly bacteria and fungi, can. When these organisms reside in an animal gut, for example the rumen or large intestine of a cow, they enable their host to benefit from plant tissues that the animal itself cannot break down (Fig. 47.9). Both host and symbiont therefore benefit from the association.

FIG. 47.9 Microbial mutualisms. Symbiotic mutualisms between cows and the bacteria that live in their rumen and large intestine help digest cellulose, the most abundant biomolecule on Earth.

Not all of these plant-digesting symbionts live in the digestive tracts of their hosts. Consider leaf-cutting ants. Colonies of these ants in a Central American forest can consume about 14% of the leaves of nearby trees, hauling each in pieces down into their subterranean nests. In terms of kilograms of leaves consumed per hectare, a single colony of leaf-cutting ants is the functional equivalent of an herbivore the size of a sheep. The ants do not feed on the leaves directly, but rather use them to feed gardens of fungi that they tend carefully. The fungi, in turn, provide food for the ant colony. In contrast, bark beetles all over the world bring their fungi to the trees themselves, cultivating them deep inside the trunks to feed their young.

These insect–fungi symbioses can be thought of as a form of agriculture that, like human agriculture, has a large impact on the biosphere through their efficient breakdown of plant materials. Insect–fungus mutualisms are dramatic, but, like the human microbiome, they are more the rule than the exception: Nearly all eukaryotes depend on microbial symbionts with which they have coevolved (Chapters 26 and 27, Case 5).