The costs and benefits of species interactions can change over time.

In addition to interactions that benefit both partners and those in which at least one partner is harmed, there are interactions in which one partner benefits with no apparent effect on the other. These interactions are called commensalisms. For example, Grey Whales in the Pacific Ocean are commonly covered with barnacles. The barnacles benefit from the association, obtaining both a substrate for growth and a free ride through waters rich in planktonic food, but the presence or absence of barnacles doesn’t seem to affect the whales one way or the other.

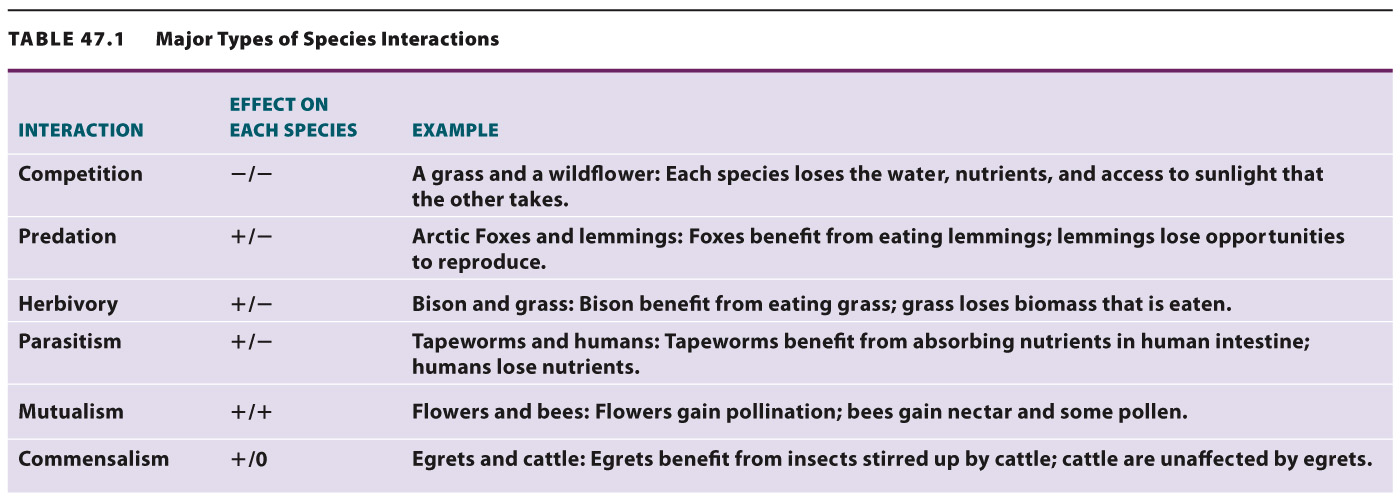

Some ecologists also recognize another class of interaction, called amensalism, in which one partner is harmed with no apparent effect on the other. A commonly cited example is the coconut palm and Brazil nut trees, tropical trees that produce heavy nuts that harm animals and plants they fall on. The spectrum of costs and benefits associated with interactions among organisms is summarized in Table 47.1.

1031

Associations are not fixed—

Some interactions begin as a benefit to one species, with no benefit or cost to the other. For example, cattle egrets follow water buffalo to pick up the insects stirred up by the buffalo passing. The egrets gain food, but the buffalo are not affected either way—

Quick Check 3 What are some of the costs and benefits to an apple tree and to the honeybee that pollinates it?

Quick Check 3 Answer

The cost to the apple tree is resources in the form of nectar, which takes energy to produce, and the benefit is pollination. The cost to the bee is the energy required to search for food and transfer pollen, and the benefit is food.