48.4 Global Biodiversity

On a half-hour walk through a deciduous forest—for example, in the northeastern United States or southeastern Canada—we can expect to see maybe a dozen different kinds of tree: two or three kinds of oak perhaps, a couple of maple species, birch, beech, hornbeam, ironwood, one or two pine species, and possibly a sycamore, poplar, or spruce, depending on just where we are. Standing in front of a tree and turning around, we can almost always see several more trees of the same kind. In contrast, on a similar walk through a forest in the Amazon or in Borneo, we would pass 300 or 400 different tree species, with almost no near neighbors of the same kind. The great Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace took note of the low population density of trees in tropical forests and observed, “If the traveller … notices a particular species and wishes to find more like it, he may often turn his eyes in vain in every direction.”

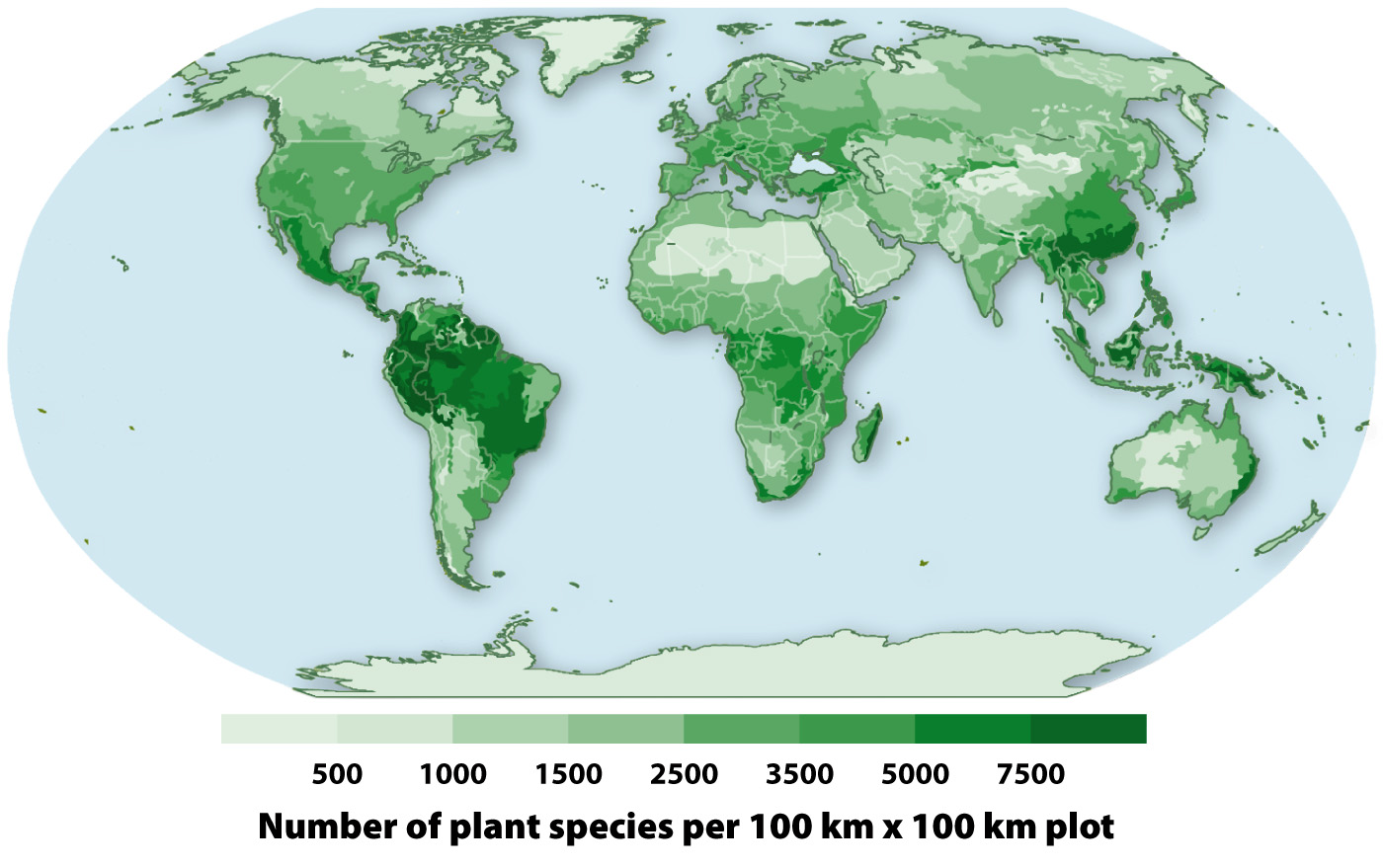

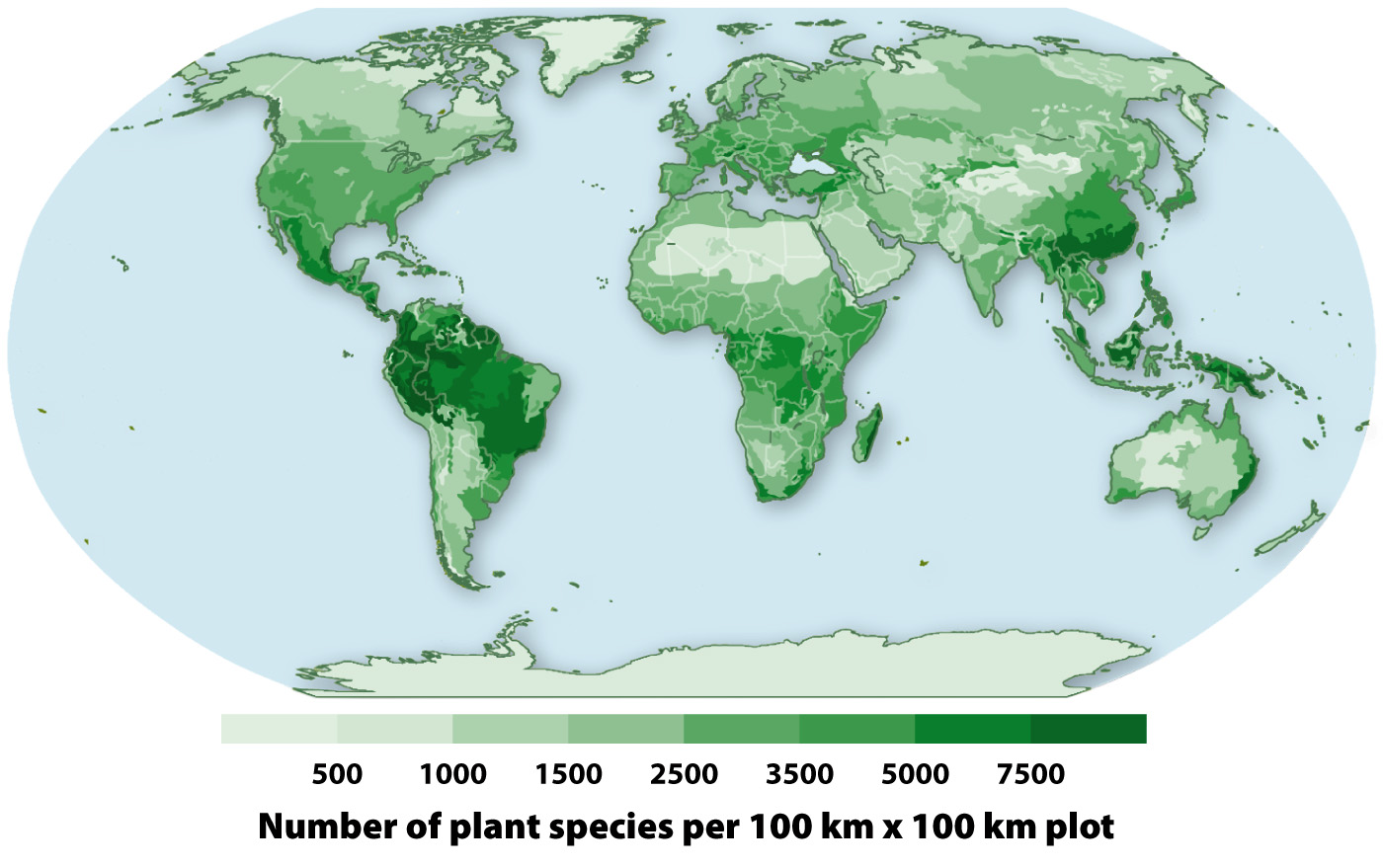

This intuitive feel for biodiversity is reflected in the global distribution of plant species richness shown in Fig. 48.21. Tropical rain forests harbor the highest number of plant species, and in general the amount of plant diversity tails off toward the poles. Deserts have particularly low plant diversity, a pattern linked to their low primary productivity. Perhaps more surprising, Mediterranean climates—temperate regions with dry summers and wet winters—can support large numbers of plant species, for example along the southern tip of Africa, southwestern Australia, and Mediterranean Europe. These regions show that additional factors only indirectly linked to climate influence regional plant diversity, including habitat diversity (in Mediterranean regions, a mixture of woodland, savannahs, and grassland) and frequent fires (disturbance, discussed in Chapter 47).

FIG. 48.21 Latitudinal diversity gradient in vascular plants. Species diversity is highest in the wet tropics and declines toward the poles. Data from Jens Mutke and Wilhelm Barthlott, 2008, “Biodiversität und ihre Veränderung im Rahmen des Globalen Umweltwandels: Biologische Aspekte” (Biodiversity and its change in the context of global environmental change: biological aspects) In Dirk Lanzerath, Jens Mutke, Wilhelm Barthlott, Stefan Baumgärtner, Christian Becker, and Tade M. Spranger, 2008, Biodiversität (Biodiversity.) (Ethik in den Biowissenschaften–Sachstandsberichte des DRZE, Bd.5). (Series: Ethics in the life sciences–DRZE expert reports, vol. 5). Freiburg i.B.: Alber: 63.

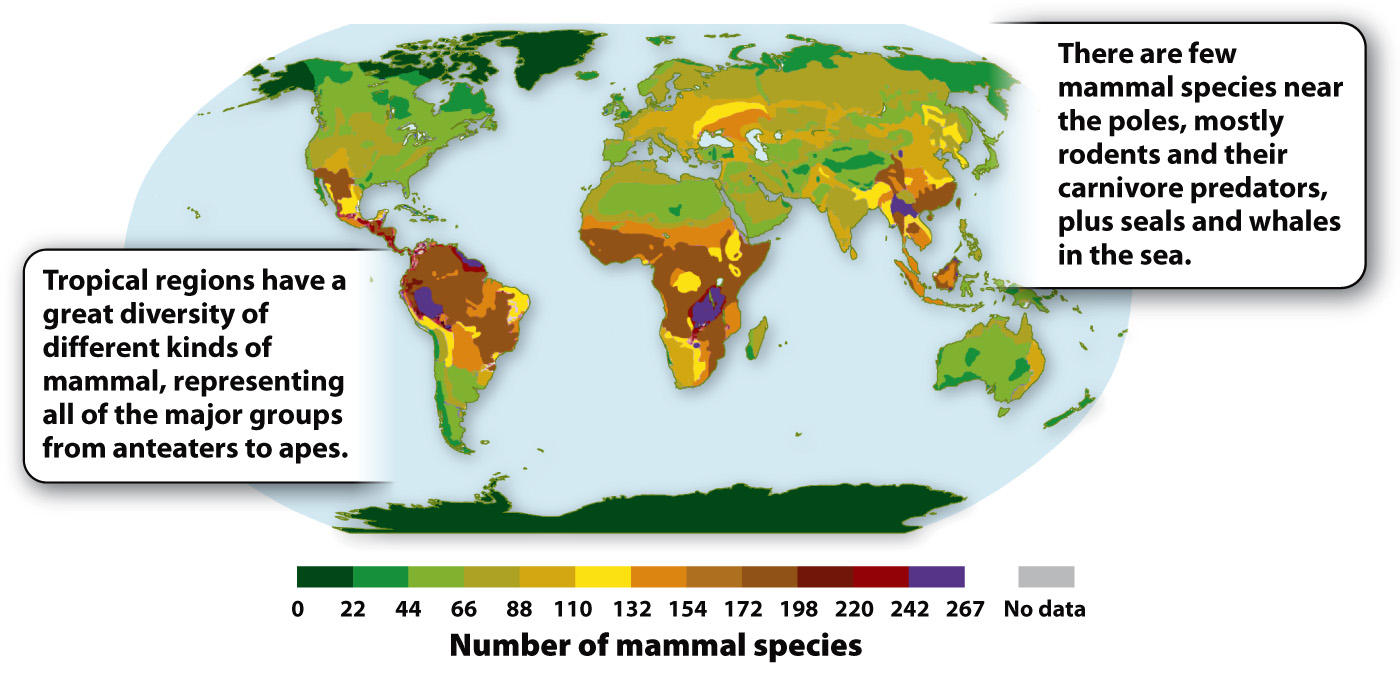

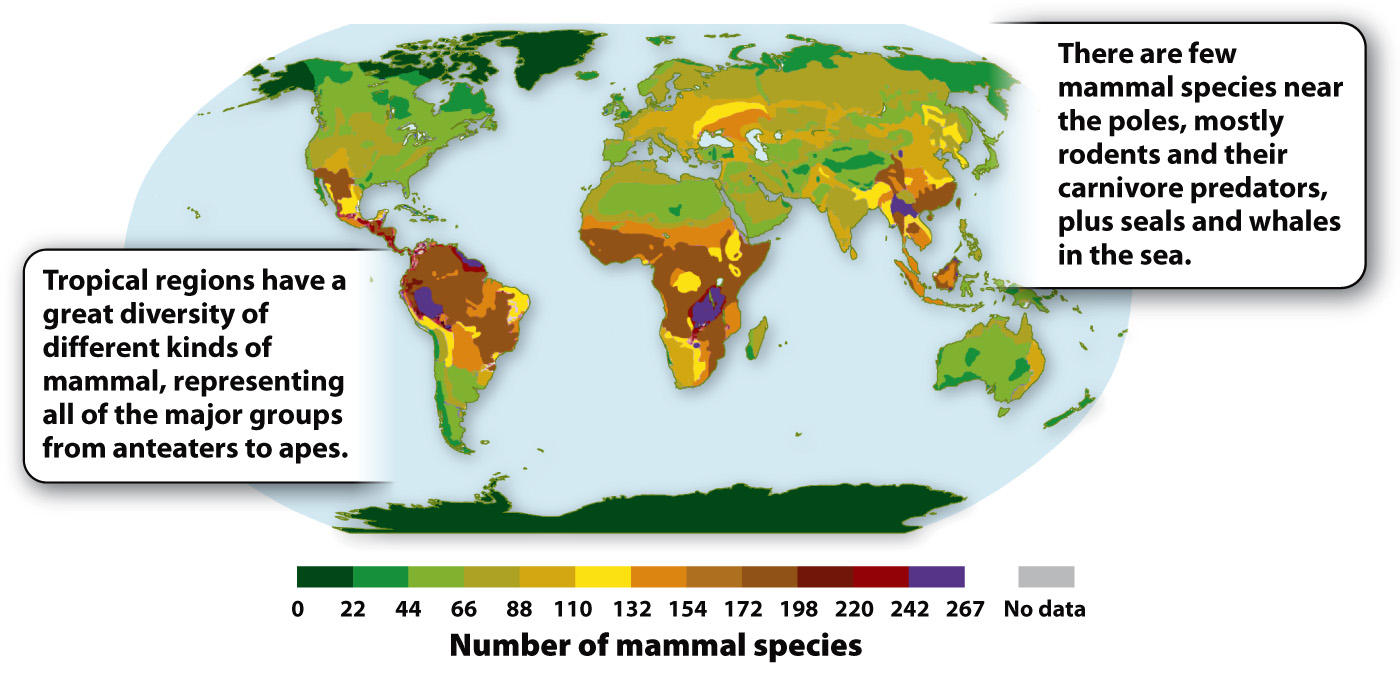

It isn’t just trees. Mammals, birds, insects, and many other kinds of animal show similar patterns of species diversity. Fig. 48.22, for example, shows the global distribution of mammal species. To get a sense of animal diversity in tropical rain forests, consider that one survey found more than 700 species of leaf beetles in a single small set of trees in the Amazon, a number equal to the total diversity of leaf beetles in all of eastern North America. A single tree in this same forest harbored 43 species of ants, exceeding the total for all of Great Britain.

FIG. 48.22 Latitudinal diversity gradient in mammals. The local number of mammal species decreases from the equator to the poles. Source: After D. M. Kaufman, 1995, “Diversity of New World Mammals: Universality of the Latitudinal Gradients of Species and Bauplans,” Journal of Mammalogy 76:322–334.