Evolutionary and ecological history underpins diversity.

Earth’s biomes are the historical outcome of natural selection and environmental change through time. For this reason, the fossil record can shed light on how current patterns of diversity came to be. In general, fossils tell us only a little about the origins of tropical forests, but, on the island of Hispaniola, there is a remarkable exception: nuggets of amber that provide an extraordinary window on life in the island’s rain forest 30 to 23 million years ago.

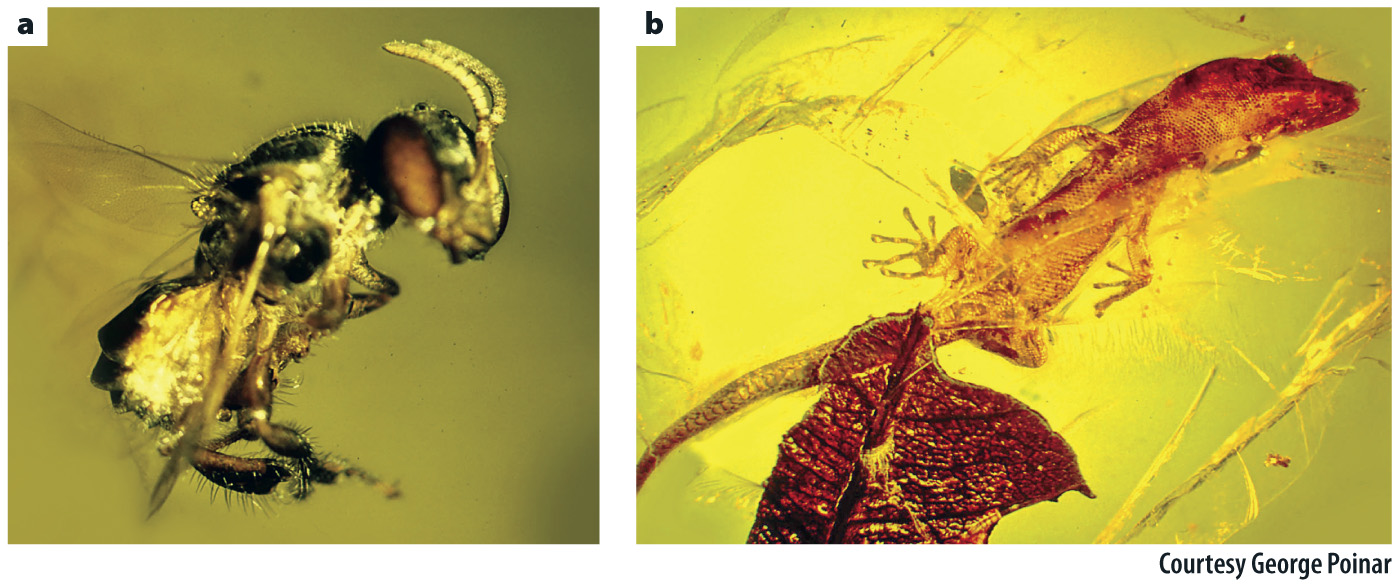

Amber is fossilized tree resin, and in Hispaniola it comes from the tree Hymenea, a member of the pea family. Hymenea trees grew in the Hispaniola rain forest 30 to 23 million years ago, much as they do today. Lizards, tree frogs, insects, plants, and fungi were all captured in their sticky sap, which hardened into amber, preserving a record of forest diversity and ecology (Fig. 48.23).

Studies of these fossils reveal ecological relationships similar to some observed on Hispaniola today. Not surprisingly, some of the most abundant animals in the amber are insects whose modern counterparts have ecological associations with Hymenea. Ants that patrolled the bark of Hymenea and other tropical trees in search of food, beetles that fed on trees that secrete resin as a defense mechanism, and stingless bees that gathered resins for their nests are all preserved intact in the amber as if they were just caught. Many of the insects seen in this amber, perhaps even the majority, are practically indistinguishable from species that continue to exist today on Hispaniola.

Dominican amber also reveals species that are no longer found on Hispaniola, for example, many of the more specialized kinds of ant found in the amber. A kind of beetle that feeds on palm trees in South America is found in amber but not on the island today, even though there are plenty of palms. And there are no longer stingless bees on Hispaniola, although the flowers they visit persist, and the bees occur on nearby Jamaica.

Vertebrate fossils are rare in Dominican amber, but they include Anolis lizards closely related to ones specialized for life in the canopies and high on the trunks of forest trees. In other words, resource partitioning began long ago in the Hispaniola rain forest. More vertebrate fossils occur in other settings, and these show that most of the birds and mammals found 25 million years ago are quite different from those in modern forests.

Such fossils allow us to add a deeper dimension of time to our understanding of how ecosystems have come to be. Whether forest, reef, or grassland, every ecosystem contains the present-