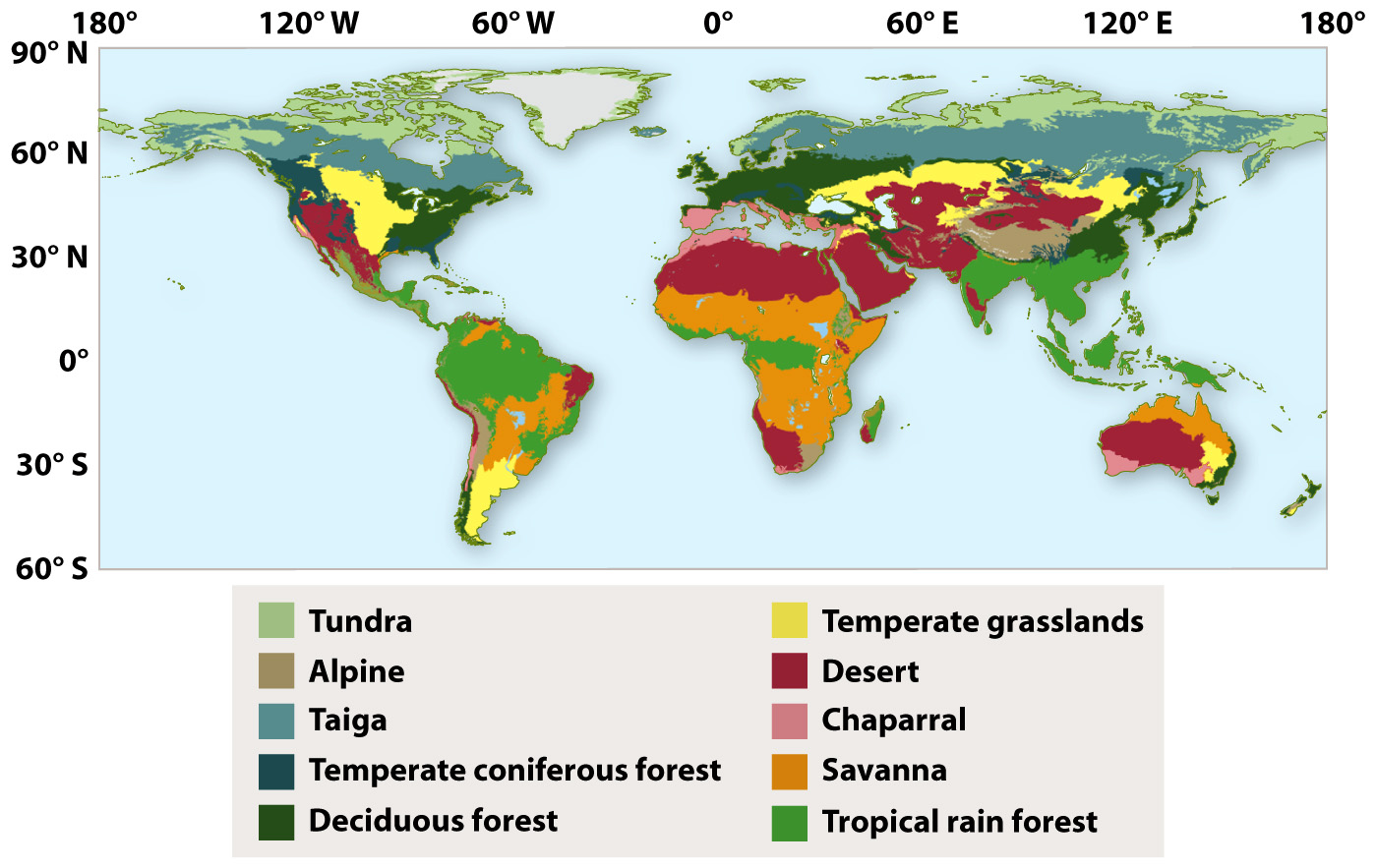

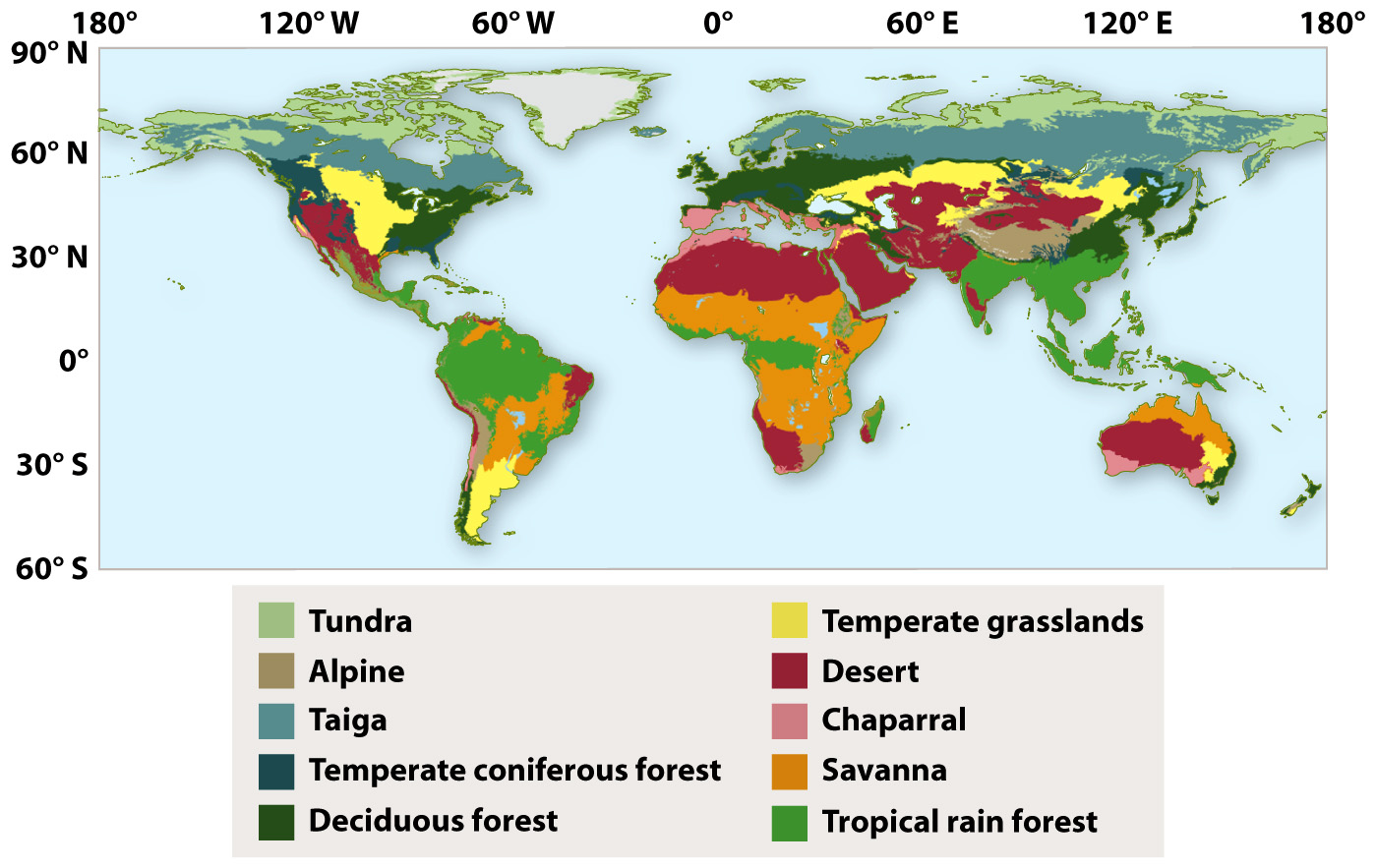

We’re all familiar with the dense canopies of tropical rain forests and the rolling grasslands of prairies and steppes. As we noted at the start of the chapter, these and other terrestrial biomes are recognized by their characteristic communities—most visibly their vegetation. The vegetation reflects the evolutionary adaptation of plant form and physiology to climate. How close is the relationship between biome and climate? In 1884, Wladimir Köppen published a climate map that, with relatively few changes, is still used today. You might wonder just how much information was available to Köppen about temperature and rainfall in, for example, the Amazon rain forest or central Asian steppes. The answer is, not much. In fact, Köppen’s diagram actually charts global vegetation; the reason it works so well as a climate map is that plant form strongly correlates with global patterns of temperature and rainfall (Fig. 48.8). In designating his major climate zones according to their characteristic vegetation, Köppen mapped out Earth’s terrestrial biomes.

FIG. 48.8 Global distribution of biomes. Distributions of biomes around the world reflect regional climates. Source: After D. M. Olson et al., 2001, “Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: New Map of Life on Earth,” Bioscience 51:933–938.