Human activities have reduced the quality and size of many habitats, decreasing the number of species they can support.

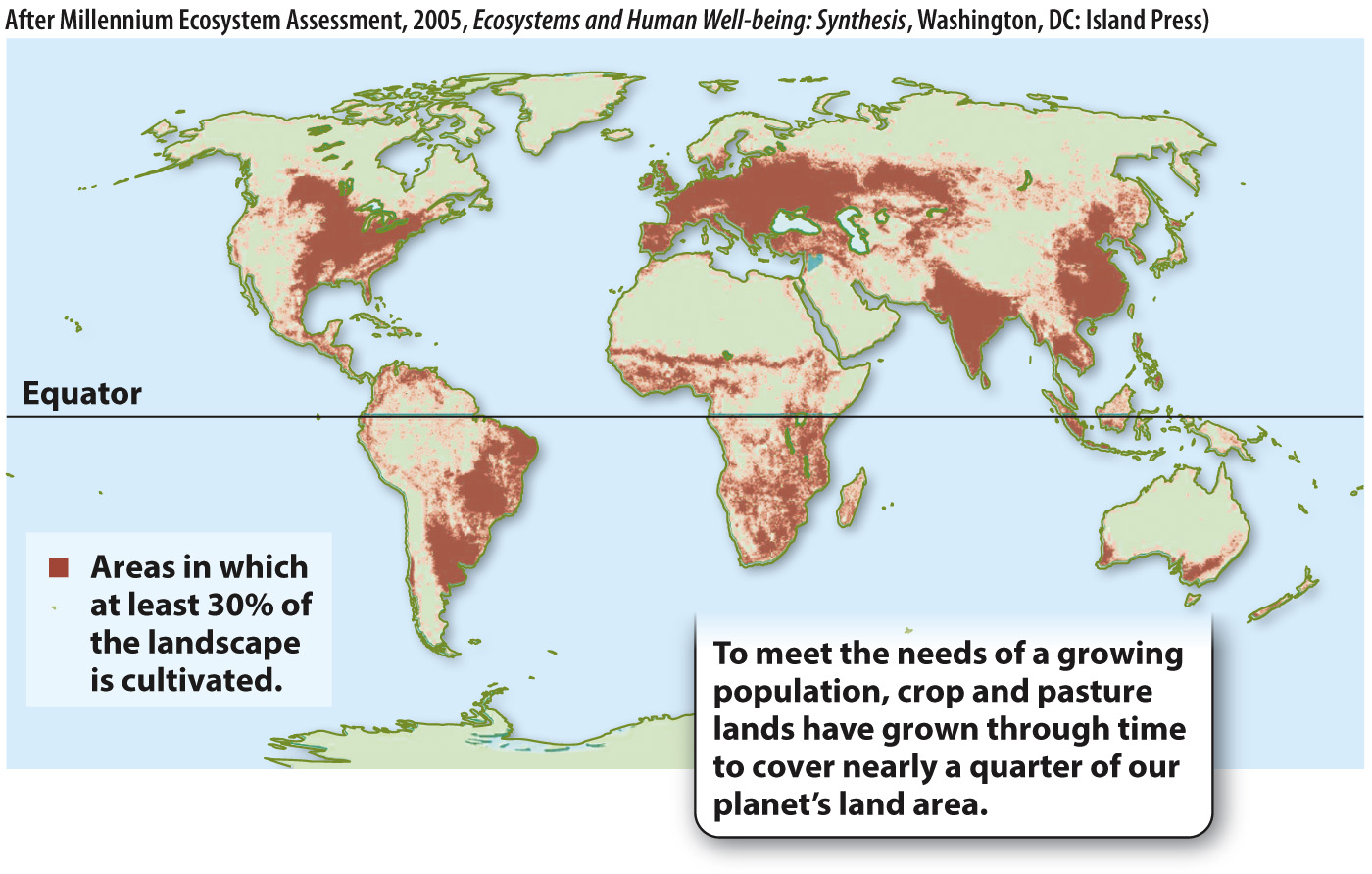

As noted in Chapter 1, it has been estimated that humans make use of nearly 25% of the entire photosynthetic output on land through the crops and livestock we harvest, the biomass we burn, and the primary production we eliminate when we clear-

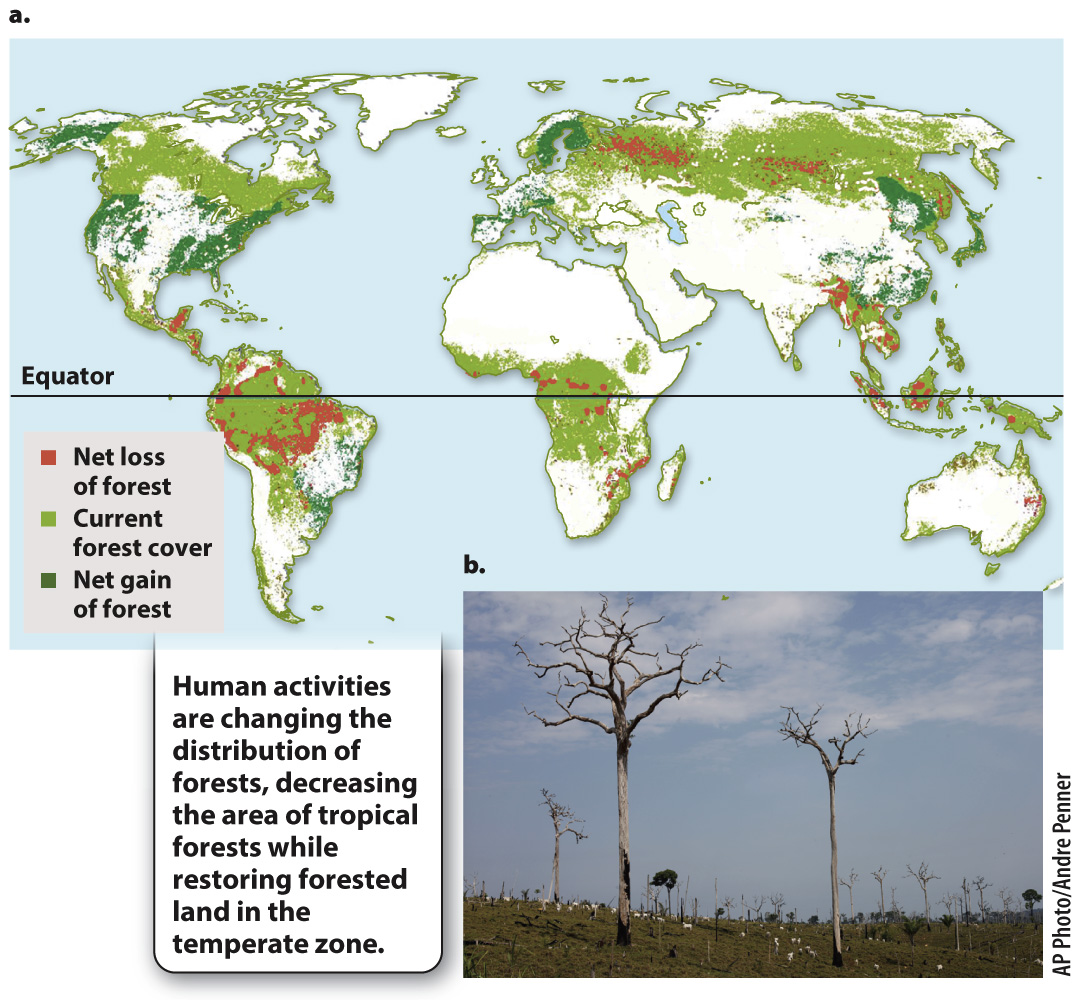

The conversion of natural ecosystems to cropland decreases the area of natural habitats, as does the expansion of cities and towns. As discussed in Chapter 46, the theory of island biogeography predicts that as habitable area decreases, species diversity within the habitat declines. Habitat loss in tropical rain forests poses a particularly important threat to biodiversity (Fig. 49.20). These forests represent the greatest concentrations of species diversity on land, but clear-

As the forest disappears, so, too, will untold numbers of insect, mite, and other animal species. The renowned biologist E. O. Wilson has estimated that Earth is losing 0.25% of its species annually—

1085

In the words of another distinguished biologist, Paul Ehrlich, “The fate of biological diversity for the next 10 million years will almost certainly be determined during the next 50–