Overexploitation threatens species and disrupts ecological relationships within communities.

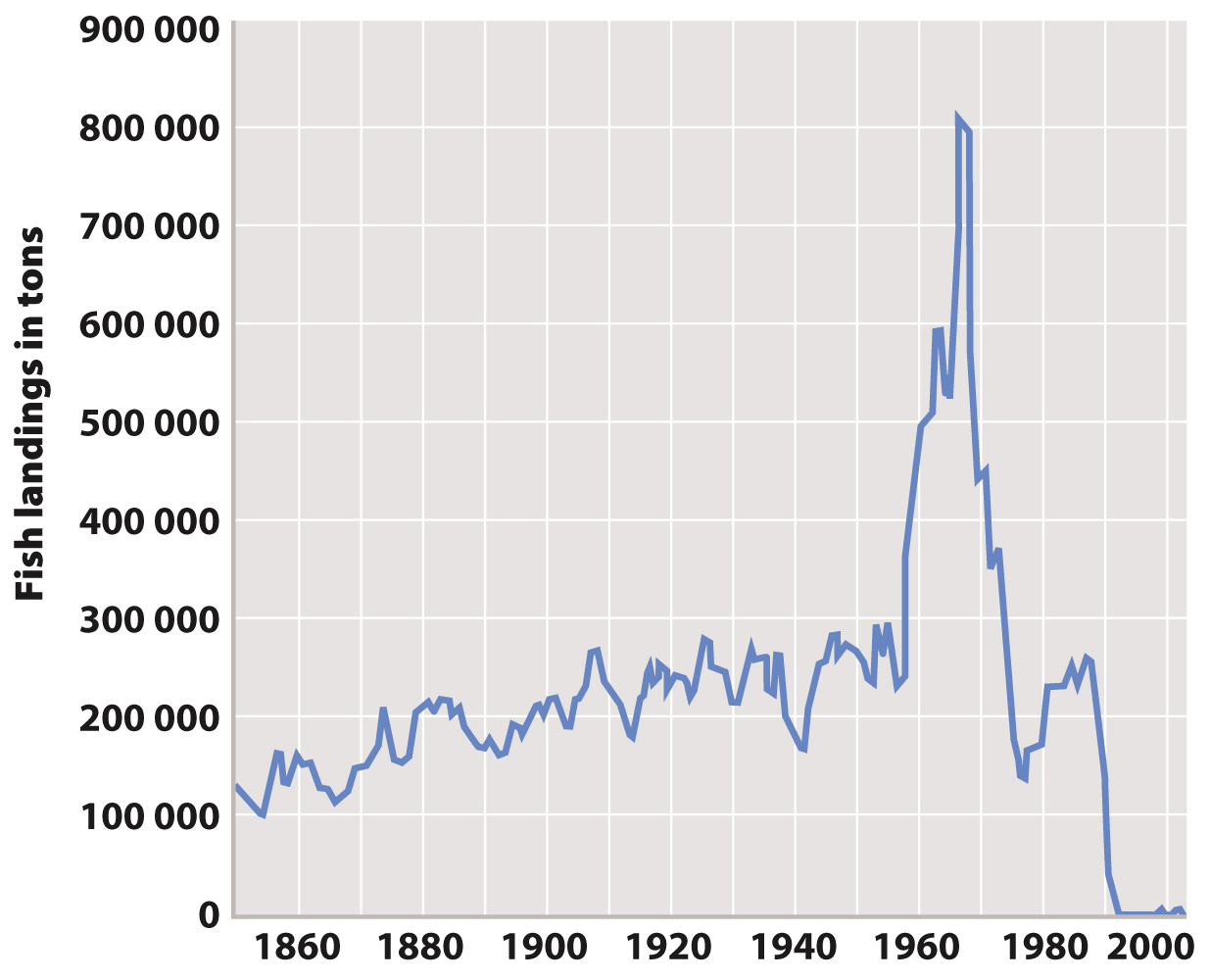

For thousands of years, humans have harvested protein from the sea, tapping a resource that long seemed both free and endless. Citizens of Newfoundland, however, know better. Journals from John Cabot’s voyage of 1498 tell of cod so abundant that a person “could walk across their backs,” and for two centuries cod supported the Newfoundland economy. The amount of cod caught each year increased markedly in the 1960s—

1086

1087

VISUAL SYNTHESIS

1088

Unfortunately, the tragedy of cod in Newfoundland is not an isolated story. By 2003, nearly 30% of open ocean fisheries had declined by 90% or more, a percentage that will continue to rise unless sustainable fishing can be achieved. With collapsing fish stocks comes a loss in food production, economic decline, and, hidden beneath the surface of the sea, a shift in community structure, as species that compete with or depend on exploited fish species respond to changed conditions of natural selection.

Overexploitation occurs on land as well, perhaps most conspicuously affecting the majestic mammal species that have graced the African savanna for millennia. A global appetite for ivory has encouraged poaching, contributing to the reduction of elephant populations from an estimated 3–