Are amphibians ecology’s “canary in the coal mine”?

In the ninetheenth and well into the twentieth century, British, American, and Canadian coal miners sometimes took canaries with them down long mine shafts. Canaries are more sensitive than humans to carbon monoxide and other toxic gases that can accumulate in mines. When the canaries passed out, the miners knew it was time to leave. Because many amphibian species have narrow environmental tolerances and exchange gases through their skin, they can be especially sensitive to environmental disruption. For this reason, some biologists see them as “canaries” for the global environment.

If amphibians are indeed our early-warning system, we should be concerned. Fully one-third of all amphibian species are threatened with extinction, and more than 40% have undergone significant population declines over the past decade (Fig. 49.24). What accounts for this pattern? Just about all the environmental issues discussed in this chapter come into play. Amphibian habitat is being destroyed in many parts of the world, especially old-growth forests that provide damp, food-rich environments in abundance. Pesticides and other toxins of human manufacture take their toll as well. For example, the common herbicide atrazine has been shown experimentally to impair development in frogs. Studies on placental cells grown in the laboratory suggest that atrazine in our food may also affect human reproduction. When atrazine was applied to human placental cells, it caused overexpression of genes associated with abnormal fetal development. Because of concerns about public health, atrazine has been banned in several European countries.

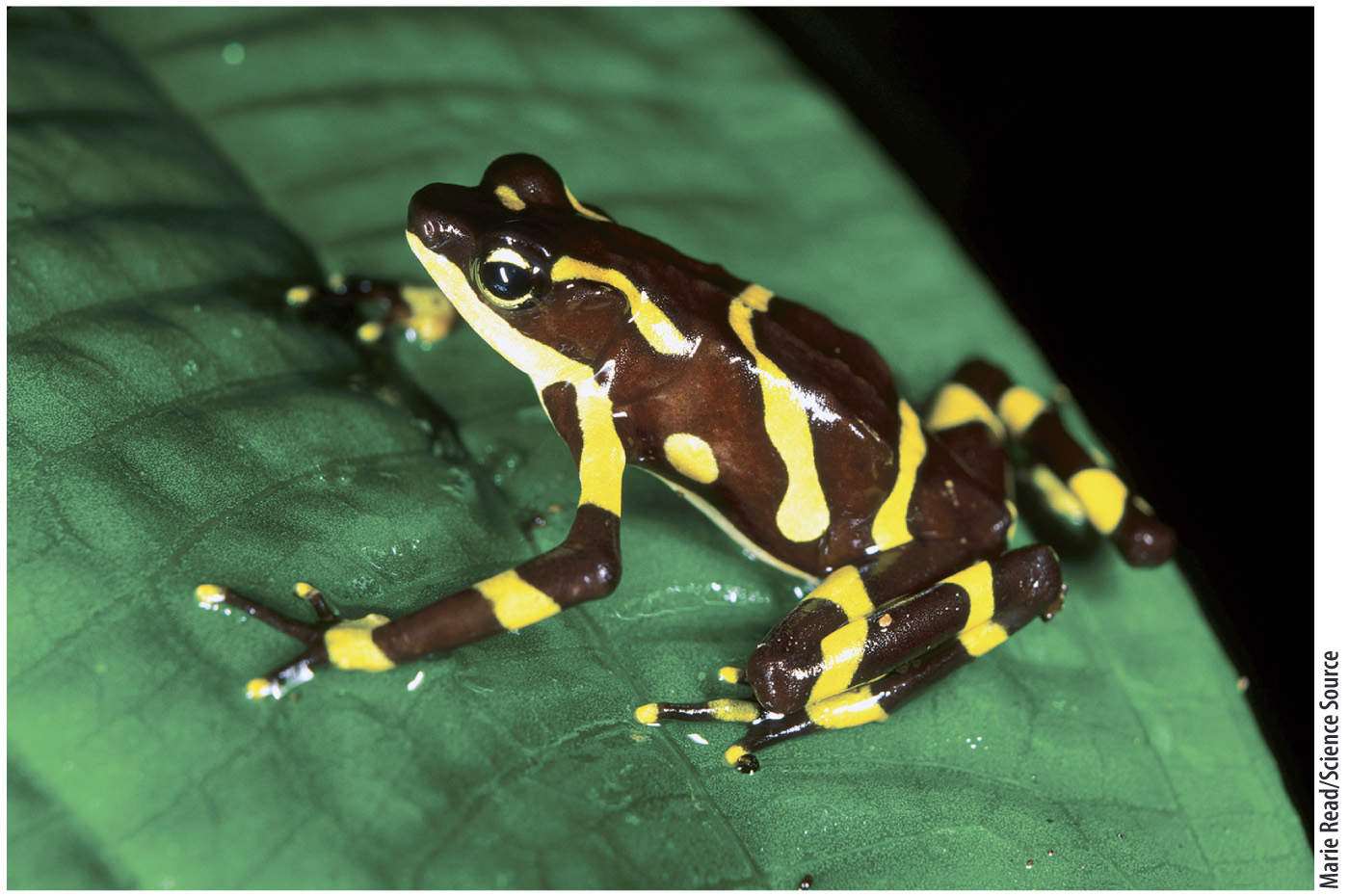

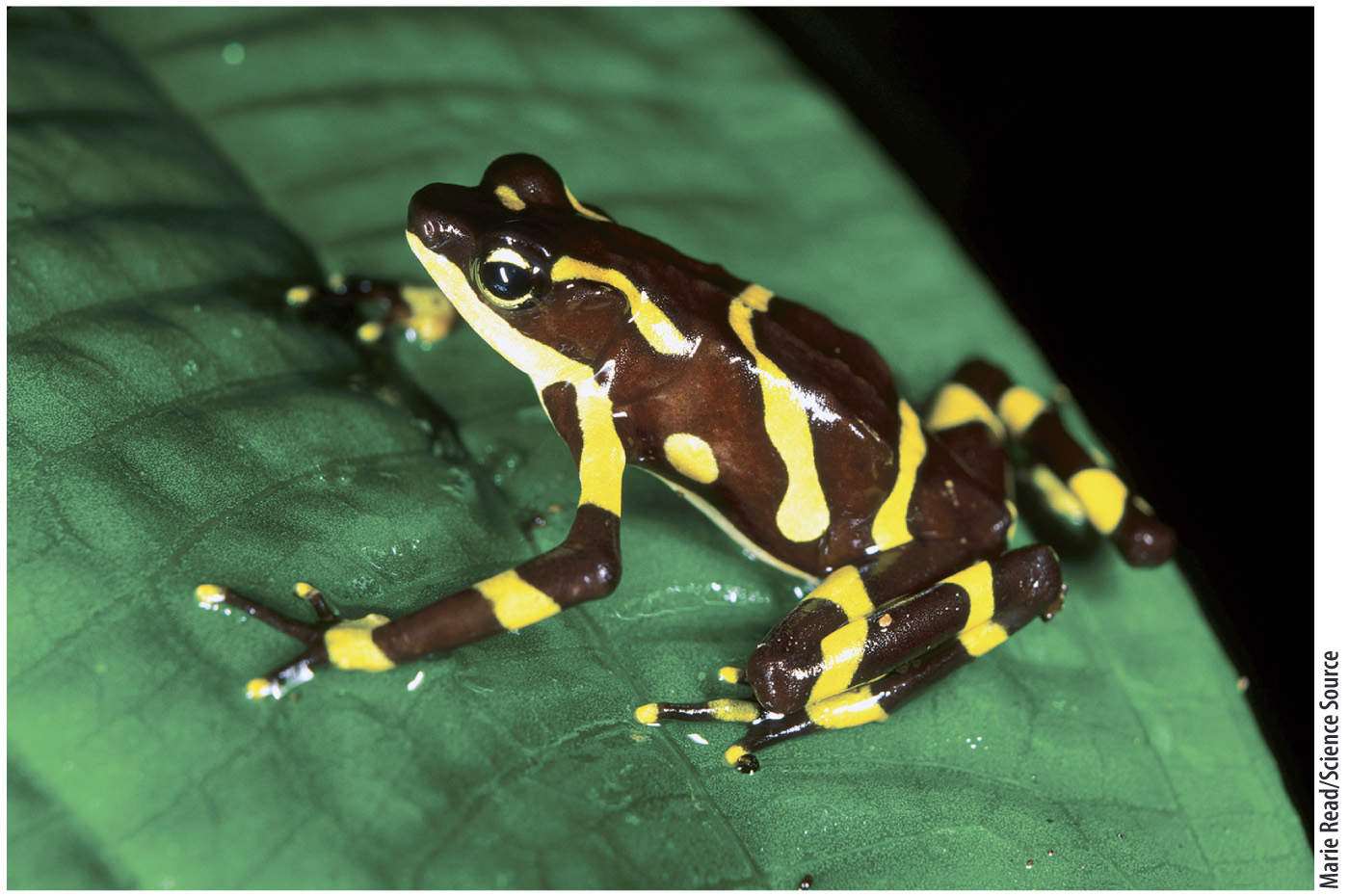

FIG. 49.24 Amphibians under threat. The Harlequin Toad (Atelopus varius), from Costa Rica and Panama, has been classified as critically endangered.

Recently, infection has also been implicated in amphibian decline. The fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or Bd, infects the skin of frogs and impairs many of the skin’s functions. Recent studies of Bd show the classic features of epidemics—rapid geographic spread and high mortality—along the expanding front of fungal populations. How Bd spreads and whether it acts with other aspects of global change remain controversial, but there can be no doubt that disease has joined habitat destruction and pollution as a major cause of amphibian decline.