Conservation biologists have a diverse toolkit for confronting threats to biodiversity.

1092

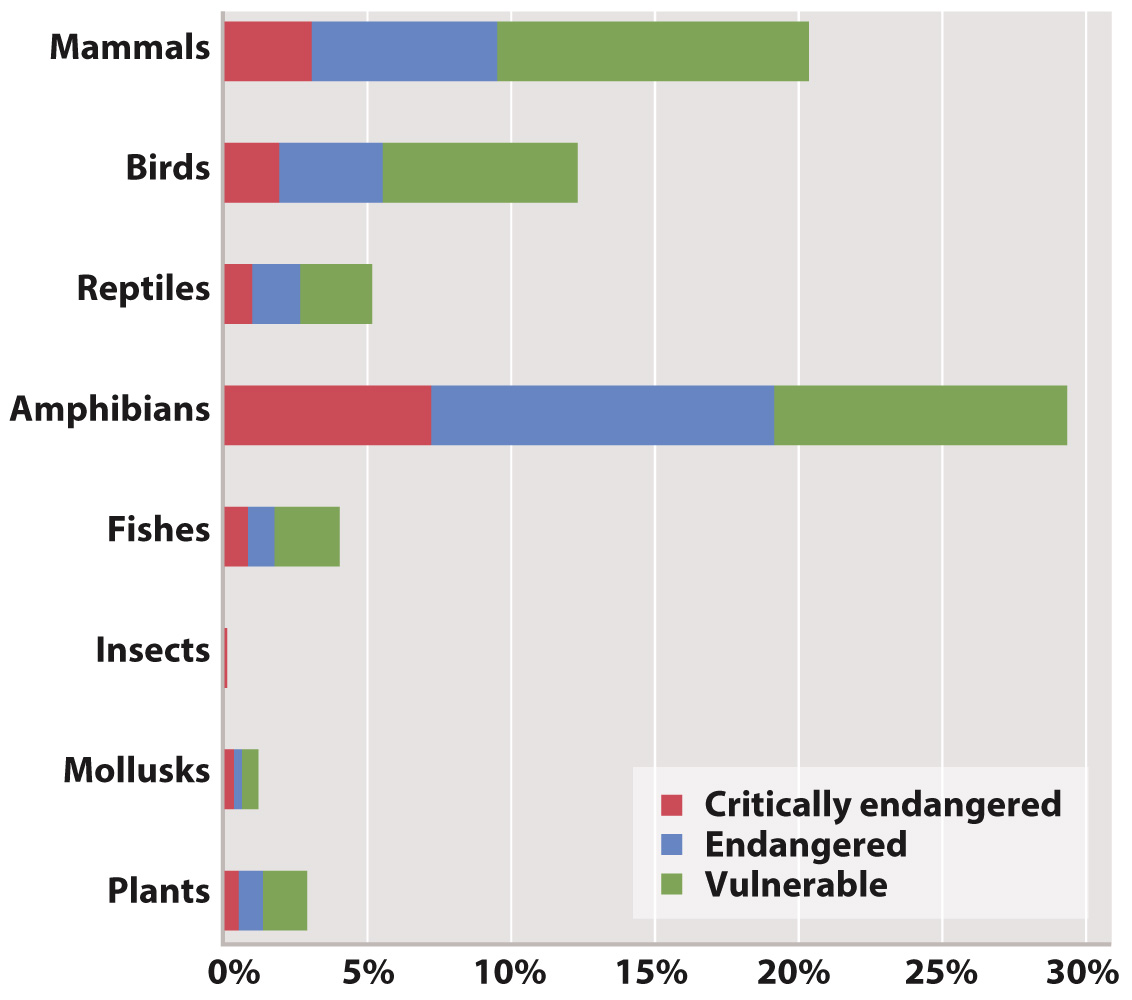

Fig. 49.25 makes it clear that the scope of the problem is large, requiring a variety of conservation strategies. Some programs focus on individual species, targeting specific threats that have reduced or could reduce populations below sustainable levels. Widely publicized efforts to protect elephants and rhinos provide illustrative examples. By protecting and restoring habitat where these animals thrive, by expanding efforts to curb poaching, and by working to shut down trade in elephant ivory and rhinoceros horn, conservationists hope to build and maintain sustainable populations. In some cases, for example that of the Arabian Oryx, long extinct in the wild but recently reintroduced to the deserts of the Arabian Peninsula, zoos and captive breeding programs have played a critical role in rebuilding populations. As the Arabian Oryx illustrates, species-

While conservation strategies focused on specific species are appropriate and necessary, they are simply not practical for the greater diversity of species at risk. Fortunately, one key component of targeted conservation efforts acts to conserve many species at once: protecting and restoring ecosystems.

In 1872, Yellowstone National Park was established as the world’s first national park. The idea was to set aside a wilderness region of outstanding beauty and preserve it for all time. Since then, national parks and other reserves have been established throughout the world, and they have played a key role in conserving biodiversity. Reserves speak to the three major threats to biodiversity introduced earlier in this chapter. They protect habitat area, and, in many cases, have provided land to restore degraded habitats. They provide managed areas within which overexploitation can be eliminated or minimized. And they provide a buffer against invasive species. Notably, although we may value reserves because they protect charismatic animals such as lions, rhinos, or bison, they actually help to conserve entire ecosystems.

A great deal of research has shown that some designs for reserves work better than others. Not surprisingly, bigger is better. Species differ in the area needed to support sustainable populations, with top carnivores requiring particularly large territories to thrive. Thus, one large reserve functions better than four smaller reserves of the same total size. Also, because conservation is commonly more challenging along the edges of reserves, round or square areas function better than elongated or fragmented areas because they minimize edge effects. Importantly, successful plans for reserves include corridors that provide routes for migration from one reserve to another.