11.4 Affiliation and Achievement

Please continue to the next section.

The Need to Belong

affiliation need the need to build relationships and to feel part of a group.

11-

Separated from friends or family—

The Benefits of Belonging

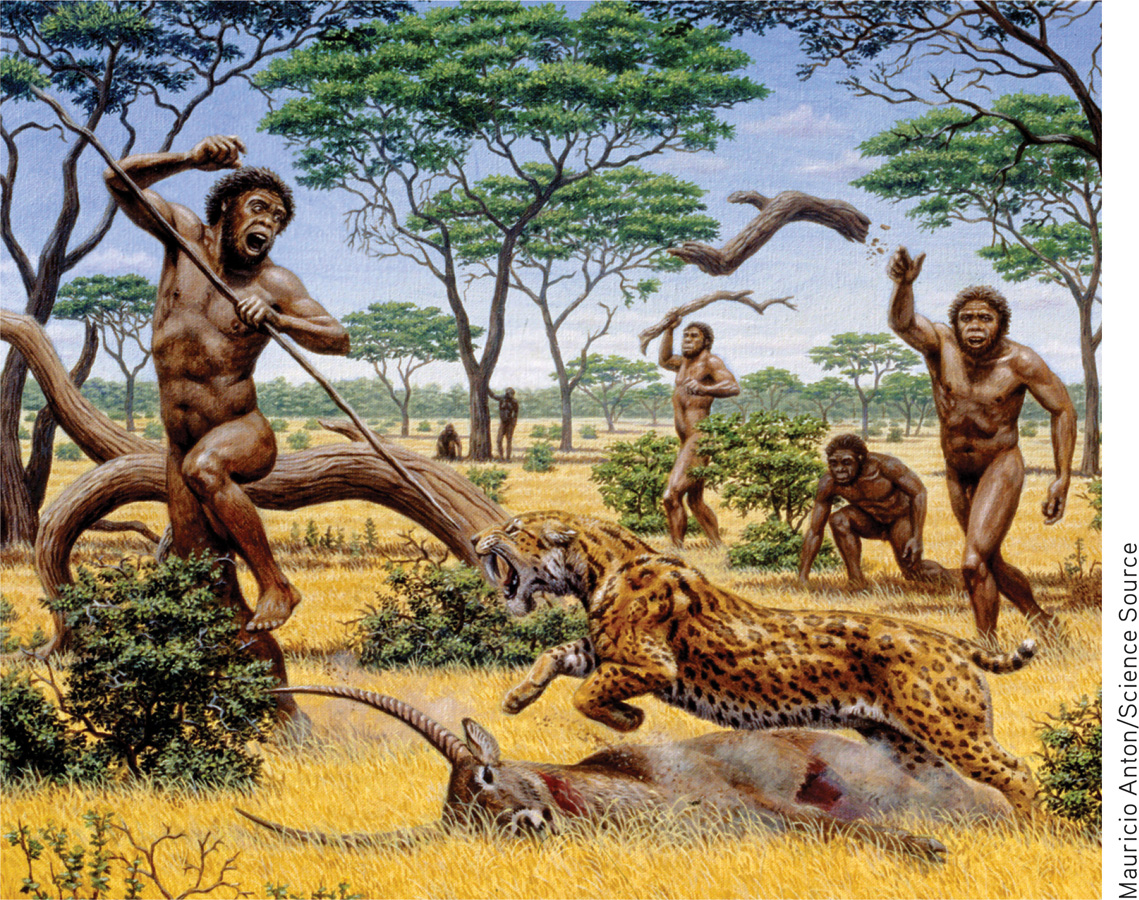

Social bonds boosted our early ancestors’ chances of survival. Adults who formed attachments were more likely to reproduce and to co-

Cooperation also enhanced survival. In solo combat, our ancestors were not the toughest predators. But as hunters, they learned that six hands were better than two. As food gatherers, they gained protection from two-

Do you have close friends—

“We must love one another or die.”

W. H. Auden, “September 1, 1939”

The need to belong colors our thoughts and emotions. We spend a great deal of time thinking about actual and hoped-

449

Consider: What was your most satisfying moment in the past week? Researchers asked that question of American and South Korean collegians, then asked them to rate how much that moment had satisfied various needs (Sheldon et al., 2001). In both countries, the peak moment had contributed most to satisfaction of self-

Is it surprising, then, that so much of our social behavior aims to increase our feelings of belonging? To gain acceptance, we generally conform to group standards. We wait in lines, obey laws, and help group members. We monitor our behavior, hoping to make a good impression. We spend billions on clothes, cosmetics, and diet and fitness aids—

By drawing a sharp circle around “us,” the need to belong feeds both deep attachments and menacing threats. Out of our need to define a “we” come loving families, faithful friendships, and team spirit, but also teen gangs, ethnic rivalries, and fanatic nationalism.

For good or for bad, we work hard to build and maintain our relationships. Familiarity breeds liking, not contempt. Thrown together in groups at school, at work, in a tornado shelter, we behave like magnets, moving closer, forming bonds. Parting, we feel distress. We promise to call, to write, to return for reunions.

This happens in part because feelings of love activate brain reward and safety systems. In one experiment involving exposure to heat, deeply-

Even when bad relationships break, people suffer. In one 16-

Children who move through a series of foster homes or through repeated family relocations know the fear of being alone. After repeated disruption of budding attachments, they may have difficulty forming deep attachments (Oishi & Schimmack, 2010). The evidence is clearest at the extremes—

No matter how secure our early years were, we all experience anxiety, loneliness, jealousy, or guilt when something threatens or dissolves our social ties. Much as life’s best moments occur when close relationships begin—

450

For immigrants and refugees moving alone to new places, the stress and loneliness can be depressing. After years of placing individual families in isolated communities, U.S. immigration policies began to encourage chain migration (Pipher, 2002). The second refugee Sudanese family settling in a town generally has an easier adjustment than the first.

Social isolation can put us at risk for mental decline and ill health (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). But if feelings of acceptance and connection increase, so will self-

The Pain of Being Shut Out

ostracism deliberate social exclusion of individuals or groups.

Can you recall feeling excluded or ignored or shunned? Perhaps you received the silent treatment. Perhaps people avoided you or averted their eyes in your presence or even mocked you behind your back. If you are like others, even being in a group speaking a different language may have left you feeling excluded, a linguistic outsider (Dotan-

All these experiences are instances of ostracism—of social exclusion (Williams, 2007, 2009). Worldwide, humans use many forms of ostracism—

Being shunned—

To experience ostracism is to experience real pain, as social psychologists Kipling Williams and his colleagues were surprised to discover in their studies of exclusion on social media (Gonsalkorale & Williams, 2006). (Perhaps you can recall the feeling of being unfriended or having few followers on a social networking site, being ignored in a chat room, or having a text message or e-

451

Note: The researchers later debriefed and reassured the participants.

“If no one turned around when we entered, answered when we spoke, or minded that we did, but if every person we met ‘cut us dead,’ and acted as if we were non-existing things, a kind of rage and impotent despair would ere long well up in us.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890/1950, pp. 293–294

Pain, whatever its source, focuses our attention and motivates corrective action. Rejected and unable to remedy the situation, people may relieve stress by seeking new friends, eating comforting but calorie-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How have students reacted in studies where they were made to feel rejected and unwanted? What helps explain these results?

These students’ basic need to belong seems to have been disrupted. They engaged in more self-

Connecting and Social Networking

11-

“There’s no question in my mind about what stands at the heart of the communication revolution—the human desire to connect.”

Skype President Josh Silverman, 2009

As social creatures, we live for connection. Researcher George Vaillant (2013) was asked what he had learned from studying 238 Harvard University men from the 1930s to the end of their lives. He replied, “Happiness is love.” A South African Zulu saying captures the idea: Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu—“a person is a person through other persons.”

Mobile Networks and Social Media Look around and see humans connecting: talking, tweeting, texting, posting, chatting, social gaming, e-

452

- At the end of 2013, the world had 7.1 billion people and 6.8 billion mobile cell-phone subscriptions (ITU, 2013). But phone talking now accounts for less than half of U.S. mobile network traffic (Wortham, 2010). In Canada and elsewhere, e-mailing is being displaced by texting, social media sites, and other messaging technology (IPSOS, 2010a). Speedy texting is not really writing, said one observer (McWhorter, 2012), but rather a new form of conversation—“fingered speech.”

- Three in four U.S. teens text. Half (mostly females) send 60 or more texts daily (Lenhart, 2012). For many, it’s as though friends, for better or worse, are always present.

- How many of us are using social networking sites, such as Facebook or Twitter? Among 2010’s entering American collegians, 94 percent were (Pryor et al., 2011). With so many of your friends on a social network, its lure becomes hard to resist. Such is our need to belong. Check in or miss out.

The Net Result: Social Effects of Social Networking By connecting like-

HAVE SOCIAL NETWORKING SITES MADE US MORE, OR LESS, SOCIALLY ISOLATED? Online communication in chat rooms and during social games used to be mostly between strangers. In that period, the adolescents and adults who spent more time online thus spent less time with friends; as a result, their offline relationships suffered (Kraut et al., 1998; Mesch, 2001; Nie, 2001). Even in more recent times, lonely people have tended to spend greater-

But the Internet has also diversified our social networks. (I [DM] am now connected to other hearing-

DOES ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION STIMULATE HEALTHY SELF-

453

Although electronic networking pays dividends, nature has designed us for face-

narcissism excessive self-love and self-absorption.

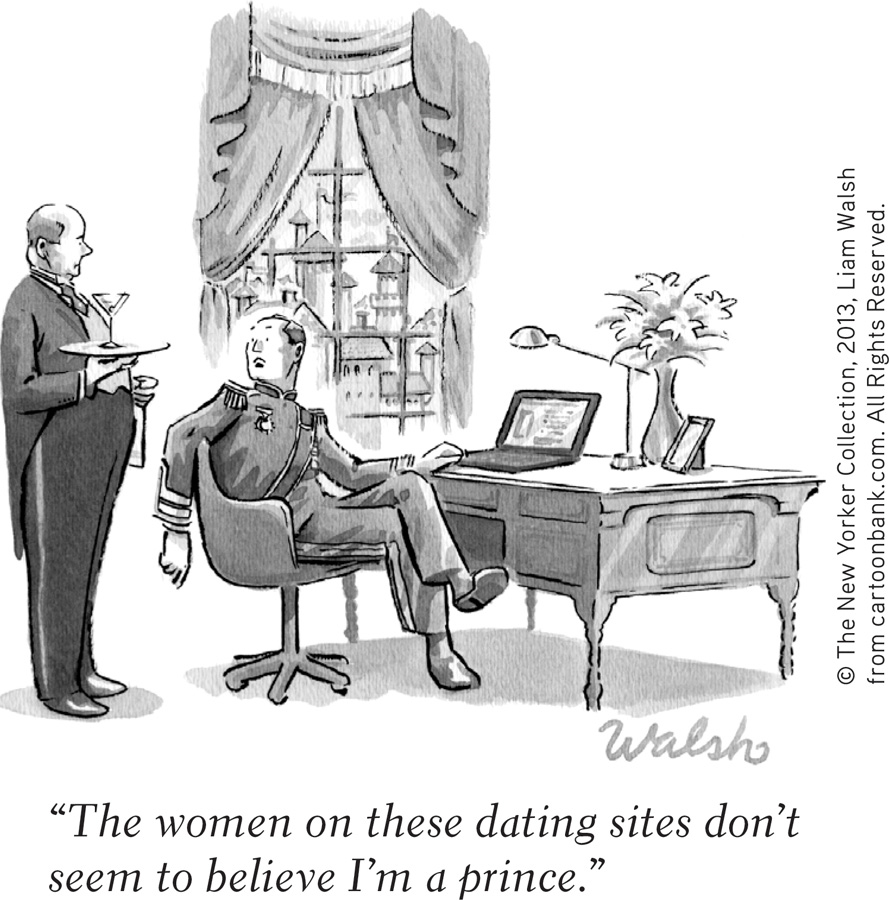

DO SOCIAL NETWORKING PROFILES AND POSTS REFLECT PEOPLE’S ACTUAL PERSONALITIES? We’ve all heard stories of online predators hiding behind false personalities, values, and motives. Generally, however, social networks reveal a person’s real personality. In one study, participants completed a personality test twice. In one test, they described their “actual personality”; in the other, they described their “ideal self.” Other volunteers then used the participants’ Facebook profiles to create an independent set of personality ratings. The Facebook-

DOES SOCIAL NETWORKING PROMOTE NARCISSISM? Narcissism is self-

For narcissists, social networking sites are more than a gathering place; they are a feeding trough. In one study, college students were randomly assigned either to edit and explain their online profiles for 15 minutes, or to use that time to study and explain a Google Maps routing (Freeman & Twenge, 2010). After completing their tasks, all were tested. Who then scored higher on a narcissism measure? Those who had spent the time focused on themselves.

Maintaining Balance and Focus In both Taiwan and the United States, excessive online socializing and gaming have been associated with lower grades (Chen & Fu, 2008; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010; Walsh et al., 2013). In one U.S. survey, 47 percent of the heaviest users of the Internet and other media were receiving mostly C grades or lower, as were just 23 percent of the lightest users (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010).

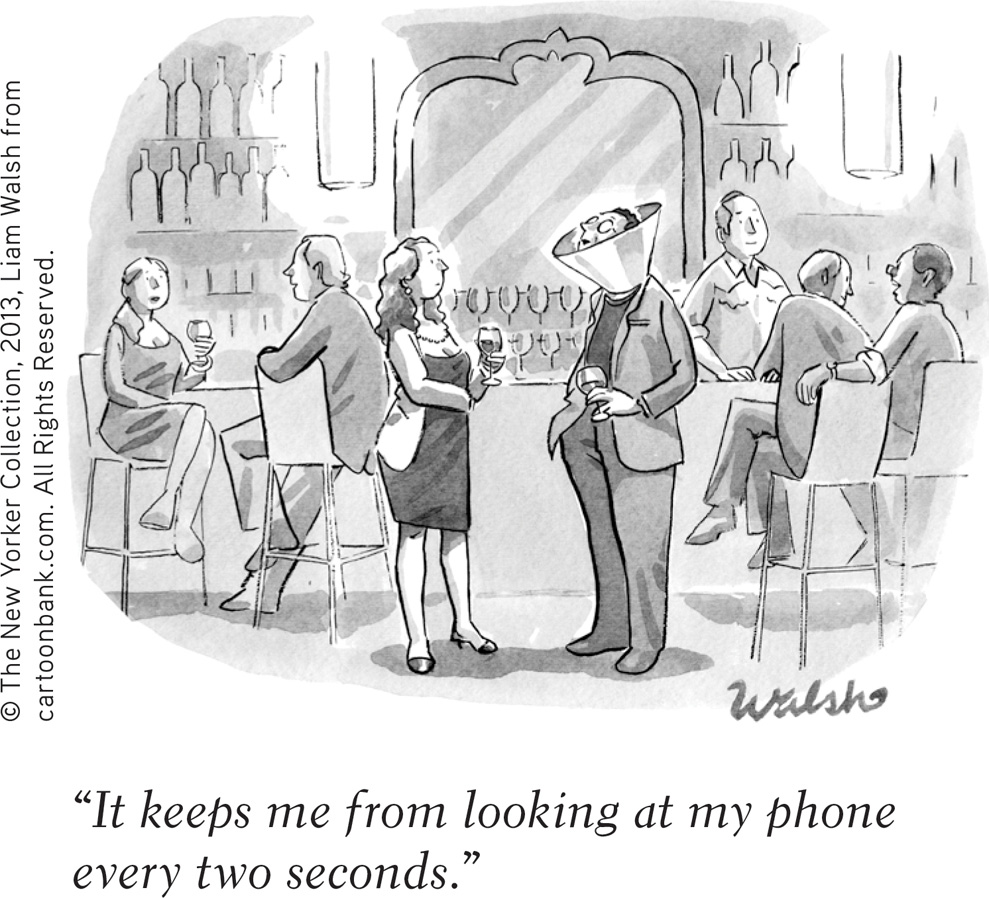

In today’s world, each of us is challenged to maintain a healthy balance between our real-

- Monitor your time. Keep a log of how you use your time. Then ask yourself, “Does my time use reflect my priorities? Am I spending more or less time online than I intended? Is my time online interfering with school or work performance? Have family or friends commented on this?”

- Monitor your feelings. Ask yourself, “Am I emotionally distracted by my online interests? When I disconnect and move to another activity, how do I feel?”

- “Hide” your more distracting online friends. And in your own postings, practice the golden rule. Before you post, ask yourself, “Is this something I’d care about reading if someone else posted it?”

- Try turning off your mobile devices or leaving them elsewhere. Selective attention—the flashlight of your mind—can be in only one place at a time. When we try to do two things at once, we don’t do either one of them very well (Willingham, 2010). If you want to study or work productively, resist the temptation to check for updates. Disable sound alerts and pop-ups, which can hijack your attention just when you’ve managed to get focused. (I [DM] am proofing and editing this chapter in a coffee shop, where I escape the distractions of the office.)

- Try a social networking fast (give it up for an hour, a day, or a week) or a time-controlled social media diet (check in only after homework is done, or only during a lunch break). Take notes on what you’re losing and gaining on your new “diet.”

- Refocus by taking a nature walk. People learn better after a peaceful walk in the woods, which—unlike a walk on a busy street—refreshes our capacity for focused attention (Berman et al., 2008). Connecting with nature boosts our spirits and sharpens our minds (Zelenski & Nisbet, 2014).

454

As psychologist Steven Pinker (2010) said, “The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Social networking tends to ______________ (strengthen/weaken) your relationships with people you already know, ______________ (increase/decrease) your self-disclosure, and ______________ (reveal/hide) your true personality.

strengthen; increase; reveal

Achievement Motivation

11-

achievement motivation a desire for significant accomplishment; for mastery of skills or ideas; for control; and for attaining a high standard.

The biological perspective on motivation—

Think of someone you know who strives to succeed by excelling at any task where evaluation is possible. Now think of someone who is less driven. Psychologist Henry Murray (1938) defined the first person’s achievement motivation as a desire for significant accomplishment, for mastering skills or ideas, for control, and for attaining a high standard.

“Genius is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.”

Thomas Edison (1847–1931)

Thanks to their persistence and eagerness for challenge, people with high achievement motivation do achieve more. One study followed the lives of 1528 California children whose intelligence test scores were in the top 1 percent. Forty years later, when researchers compared those who were most and least successful professionally, they found a motivational difference. Those most successful were more ambitious, energetic, and persistent. As children, they had more active hobbies. As adults, they participated in more groups and sports (Goleman, 1980). Gifted children are able learners. Accomplished adults are tenacious doers. Most of us are energetic doers when starting and when finishing a project. It’s easiest—

455

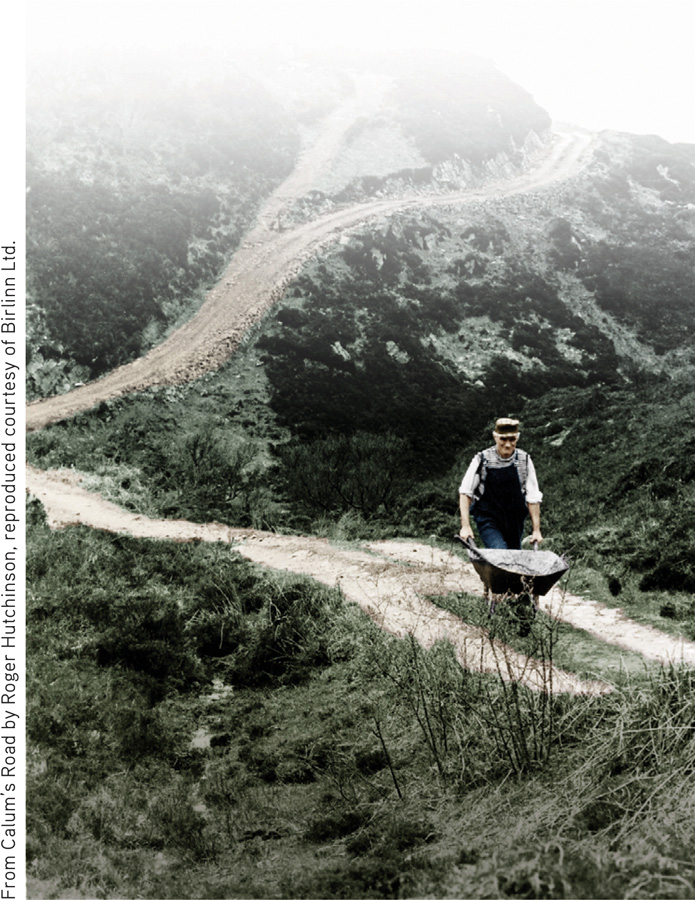

“With a road,” a former neighbor explained, “he hoped new generations of people would return to the north end of Raasay,” restoring its culture (Hutchinson, 2006). Day after day he worked through rough hillsides, along hazardous cliff faces, and over peat bogs. Finally, 10 years later, he completed his supreme achievement. The road, which the government has since surfaced, remains a visible example of what vision plus determined grit can accomplish. It bids us each to ponder: What “roads”—what achievements—

In other studies of both secondary school and university students, self-

grit in psychology, passion and perseverance in the pursuit of long-term goals.

Discipline refines talent. By their early twenties, top violinists have accumulated thousands of lifetime practice hours—

Duckworth and Seligman have a name for this passionate dedication to an ambitious, long-

Although intelligence is distributed like a bell curve, achievements are not. That tells us that achievement involves much more than raw ability. That is why organizational psychologists seek ways to engage and motivate ordinary people doing ordinary jobs (see Appendix A: Psychology at Work). And that is why training students in “hardiness”—resilience under stress—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What have researchers found an even better predictor of school performance than intelligence test scores?

self-

456

REVIEW: Affiliation and Achievement

|

REVIEW | Affiliation and Achievement |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

11-

Our need to affiliate or belong—to feel connected and identified with others—had survival value for our ancestors, which may explain why humans in every society live in groups. Because of their need to belong, people suffer when socially excluded, and they may engage in self-defeating behaviors (performing below their ability) or in antisocial behaviors. Feeling loved activates brain regions associated with reward and safety systems. Ostracism is the deliberate exclusion of individuals or groups. Social isolation can put us at risk mentally and physically.

11-

We connect with others through social networking, strengthening our relationships with those we already know. When networking, people tend toward increased self-disclosure. People with high narcissism are especially active on social networking sites. Working out strategies for self-control and disciplined usage can help people maintain a healthy balance between social connections and school and work performance.

11-

Achievement motivation is a desire for significant accomplishment, for mastery of skills or ideas, for control, and for attaining a high standard. Achievements are more closely related to grit (passionate dedication to a long-term goal) than to raw ability.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

qgYzCTbeqAwgxw7lr8Lk1EmY2AUCBZHp606e2ODGI4Hk+RKRSMh2ikf4MkVVJ/CCZ4jb18QiMFCqh8BUc1fKE+Y72Nq+xda14j09KyVq4Rgt4YbFw8y4VakCa7YNxBDxXgXqHDHC3mTHoI6x80dlMJNSJF0FYeymDaaraBg9N6PVWYqLWABqr/iT6etdroQ9Pzhwmeg7d0g+EHtQ8LjUSRIGGCzOXbAzmwXZ+8kusYhm1Lya0T6RE30AqE2BgWSzzrso+bWIQoiLGId6avNlm8GCn0wk9p05V5tvgxjidy32kl2Krj76WNanPZ3JQN5hqTD6tzqEB5qxFLkr5qwBWZjfH8o8IpsjJu7jLxDBAvDGlr7leffRsy4UVwB06gnWveOk2lOvc7RR+DH3g3xnPb/cHPQuc+4wiDYcjRJALmXKXrRQbB39igOqC8YgQuRXU5eZyHqJgudo8OvojDHPfnTqsQXhDrJUuIouL7iK35+lcz5PDXjsOkas1BE22tUdcNHzjTrJwjD68NQ8um69wDzEd+IPreYReg5GhpSrMXJIpvi9JbSIFdZUZtMYSPbYdgT1dA==Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.

TEST

YOUR-

SELF WHAT DRIVES US: HUNGER, SEX, FRIENDSHIP, AND ACHIEVEMENT

Test yourself repeatedly throughout your studies. This will not only help you figure out what you know and don’t know; the testing itself will help you learn and remember the information more effectively thanks to the testing effect.

Basic Motivational Concepts

Basic Motivational Concepts

Question

XFZcv82LdrOf+vDJGBuP6gTISyhcsKhJ4AABC9oEPhBWKcK9QSNGnbJYqmedQX6d8rC0oolFkjuhfSQkjcxPnrARBzdiucYyfAwiWFs8wfOgtfAkKLtXFpPlv/MX1jdai4qRR1Ed1aK8D9wT7eW5TmLHmgHH0zHGkAEL+MaQ9NY6B/lmaJN2uiaCm6WknAsTQJUCVUbUb+Z3e/6HVBuxX935HoL8q4tXSy1Ud4X6+37vFOxMKyvJ+pp6jDwH/xTxlHikujC/kcWZFw4RzsGkIWa9zNYMvKJK1fFJv+jMx1vOrEZmGX1aI+nvLx5IPNMktKFKatJ8Meq0bZ0cWri9DEfCXGAFr6ZxwAYwMhKXnEQYXQP6GWhycah5qiZUg0Qy7tvJ4vnm4Rvbz0LgnOsmQ2nMr2dHOtuFcoKQxzuJERyfco9+2EYOz9+moxhLtmWKCDAhRqabWMANK8pzdjoxPQcLS2k=Question

VJ30dIuWMpxpV9BXw+UtHTHQT9rOlSss/fg1q8uL8L64BSXthKYNRbiTmXt8s8iBaq8zgZlo7KlZ0EshOCQ62q0djINQudx9aHPL7u9WNZrO2QCnZDeGlwpDBzmOHbZ5+Aj+wxekVInr8Lm5oJnrn+Z2wv4CU8ZMav+IUDbK1Iu6oVlH1+3DJ/QId/uRDqqLPL8h6xDkP+tR4RnmE/Ti4TWZ4KTlaC4wra3HduGWEZV6RAiEMBzaE6894s4c1ONUVlSE7vwblTTvrc82w+zxM58OhMjAw655UPkS7gbAWIvZYjvCWPYmRPP4OdMyvAbvQ6OfId6d7tBcBxIaRl1HN9G1kOemLHvxqR0HMF7gxRpZw6pt+kJYhmJ6luVVKi0pZGtQGF9Z83FIJ2oS+g/x1hHjlrjKbKGoQuestion

3. Jan walks into a friend’s kitchen, smells bread baking, and begins to feel very hungry. The smell of baking bread is a(n) NvvipvPDwc7lOS3q9jW30Q== (incentive/drive).

Question

4. /vc0m90/eihHwGIh theory attempts to explain behaviors that do NOT reduce physiological needs.

Question

y4mtPhxpl2QsJFOvNIvkO996m5Vaz4pCzhSccNpPxWu+/U8SLau2O16S2X2q68GU4gMLW/D5Z5czQwp3r99/GvnjRjikQKKURqLg7l/olM7VWAtbSCVm+1HhSZPMJ/peMgDdcpL+fxmZluhzzHlOmV+XGIt3+gDgnMRaxQGhE1Bejrk7v0lDjiDI7oL5lVVh6w2KpCyiMAj5QVu3Eb7v2ReUtSDQm9B5EVjns8uvo4ttpx7nYBAhLdMqow/HDztxLgb0owf4fOA3t4ZIQuestion

qqPca2IHFqXMD00Onc26AXORMTYSEHe7zI9sykvB6aZH9VJkya7c/LKGVjrb5GmioTBl9VCaXGjZhFseVWxI77KwSXlqnpSMY/ePuqzqfqz2eQME4soRO24XT879uMzNOXqTv9eUZkni4I6VSMUP51LbdNhm/1WT0PC3uOOGNzraNLGQvByRoEjCmAuvoaVd8Q4tfKelwy75ef/MwYckr/BTdEb2Ky7kWPPIeLVD54zQ57DiaV7cTjgyGnUqDKgSiAGWgF9KK5N4VSzjdJ3tSmni+adU+TiDFmvBOHNo6I458+WWQL3H8Q/BkiVG1eiaW1cSt7ou8FKMIexqvTS3u01NW6hs2NpnlL0mRBbpBg8= Hunger

Hunger

Question

8CKZzhQ82azsKvwROTZVSTiNDv3SDNDO9XfzLu/Cu2TPZ6c6aKxzWWGGmKBu6iiuusRmZdU1gjFIuwBkZMntlK+SNqPzrfR9TuoBhu1EA7OCc+tWuAZJbf6CKj0HD1dsb/652HeO7e5YPz2yXLQ/OZgVmJXkCMqbUuqPfouR8Jbbu2iUwz6TP+R6els1Ib0rypX+IT/mA/TMDImTLDXjJN0iQcVQyZrGttwbSOXlXZ/U5srq4V3TWg==Maslow’s hierarchy of needs supports this statement because it addresses the primacy of some motives over others. Once our basic physiological needs are met, safety concerns are addressed next, followed by belongingness and love needs (such as the desire to kiss).

Question

8. According to the concept of set point, our body maintains itself at a particular weight level. This “weight thermostat” is an example of xprjKy4t8/6sWyvHLukkWg== .

Question

WW1XDKqrVzDMr/7dQA/cQj6DtJo7KWbRxuctzRPOtA9wBbG4i5oRSfPjeAhMuKKuIgdyOWDoTtH5QqHaUwFLOxH7dr0qC/vY9mxJ8s56BhM5/aR5s1VUOKQI38SyXFUa3a2yXl63kyDFot8ZBNbwdmT+Z/L5QCjZXhH4WiHQRcvw3CrDv8IejyA51nIg/TR7oqXAJXHyJrka0xFAYVG/rGTROhbviZTpkym0nnQr9to527vgxLlfMC7mrccw7xXNg6a4qRjyNse/eFrI6cOIADMiSj774F6dhulNNOKtQF4Urbr/T9WMQEjDSZVagAIK6GFeuUHUzRPkLFhvjBkpxZUUrhA=Question

10. The blood sugar bbGfqnX2Z5nRy7Ib provides the body with energy. When it is lg05kNDUDyk= (low/high), we feel hungry.

Question

11. The rate at which your body expends energy while at rest is referred to as the WLAezbSAomm1f3AH p/onRwUYKn0rENNaxkdM3Q== rate.

Question

X4PyXsAu5HTRWR1eokTDdLr5eW3GWzdGyIwRvEoOAxxcOt+GGG4JLCqCXADTIJFc4MellBTL6e9mswHBXOZBJQi+2FY+pXmmR7VwIdbSkEP2xBkqX4zrcES4VP6k9UBZVtPvPL8GsGvkySybIg2kt51SYnJEfZ5PpRXTAIe3yZS4ATlqD43dVUsIij0Fhw7ER0vZsia5xTyP063bgfo6OnJ6R7RXKiQ1od5tRlnDpoUiOQhiUKDdw/KCmtO4semAAAKNKz23jPSCS2jbFM1zdhjvHNBaZ/lKlFk3zbPXIsr0q8+AJ2IS07XlQPF7wJuXad8k5Hq9upe3vrrt/OkcCNIWRWosldrWfPCMcv8fFmR00BZ3DhNeSzVD0+GrF+LZvORQag4pbAEUUxai9cEYhJ/MVyMl7gWUg5Nv//Fioj/Sx5+RR1e+sugd9WANPhMRMy1DQmmWT3I=Question

ekL/MLOFsIe7yELhut1GdjjUXee/nXrTsGC5VUXg1B92gPXmT6gUDCcJGuq5H0sdWjv+3AWT+9C64EI2emn9groAQFg3w9FZnrLkUrvgkDUpOS87zJhU/dLG6MxODl/H1effrFbmWb9CyqzIz4xqbAE6rf5WNxs6pPSvM3vUiMImg6k7MTphfktPu0UlR4lZ8+XS4ggMFRw1CH77VWdD4OayGtLSiwgWa5RPrsnZEpFF0iTRAOMVMx0BEXwweOn/X3L95zp1LOr8vg2YmigmgdOBLv5xXK7tQ2KfpwLRoYNRj7MzTCJoGQWvQHR3x0DVDU1mhLyi5/31BsViSanjay’s plan is problematic. After he gains weight, the extra fat will require less energy to maintain than it did to gain in the first place. Sanjay may have a hard time getting rid of it later, when his metabolism slows down in an effort to retain his body weight.

Sexual Motivation

Sexual Motivation

Question

keGg4FDdgWgFRjB0jL4yuPGeDwINQ7pxULyY4BzCwUkiamIIm07sBUOOJDCQhyyopVQEDYcu+8rnLoKth2WkzlU4u8+83Z9E2pVV885VtOqnMbhSU0QOb8pn0WTi73FPsEPGJJkgAS82v+VCuWGvEG3b4nhO/WBrgQjNPaHxf9ZtJPNl+6fFBO61fOh1SIm5Uz0aUS9AwHOlkBXGhSpVXjeEXzx+iTxjNqbCQwiCZUErTerTdr2vAMP1AhHlMZAAIOefeqeRVm3QR8gTSvfaue/k0WGNERQzvzZcnZL2xD0Ha+ZqXI8I/tJslh7OZgweNrqc8Z5R5IUZEWSp74h9hXeTRTqcQyDVrRiYHmg7AjMDOvHFtru1tL69E1X1ZsvCuDnehm635vUWwPLpybjP7jhKkHjLlzmciR/tVIytOHMKPAokQuestion

vymT6MGcC5KLe4p4O+9dv8m2qyZT8lHUijc2YGrj0quc9oSn4dd1w8cIHkMemb5nGMg6A03uUpvq1VlAHvuYeFqcoN1Qwb6XYuykzNc76nmPhE9f+OcKZEW9BifsaLB0edJD9RWu0+aWMk5EPr1PaFpzbZXBeGHBF37TD8j1xJYBUsT9eZXqTyXAkmpXmtZLN97/72oH/JqWTiOCBw1tkeJ+q+Npg0BWkVZJzFEO5I4pFd9pl502cpDLzavfshOvRgUuaatBVQcCGFPSY2cf7/T7YMd+m//xlrqLXWJoCwKwsPXVv3hawj4Hk0t9+aUoiqomJ8j2Zq6eeEaUS1r+peatMQ50eSRnQkAWLm6USfsrJUklqVgLOzhGc3G3zapvsBcPwZmV9uuW08tV/pclyenMauqNPJM/pBVGPMVthGeqnKQSvjam4JVJguXm9GbDAbOeQYBAKJ98RXV5a64qfh66jpz98mLub8rJVg==Question

pvv0fSJl60Dx869ngWPoy7WPg8eEUSpWbv8kynOtSwVjwOnECK2N3iGwlTlmVUr+YYp4O1Fokc5GcxWCx5pNGA6f/eTRF8NZBzbZqKcU4ln3huxuaJcl3PD4O5o=Sexual dysfunctions are problems that men and women may have related to sexual arousal and sexual function. Paraphilias are conditions, which may be classified as psychological disorders, in which sexual arousal is associated with nonhuman objects, the suffering of self or others, and/or nonconsenting persons.

Question

17. The use of condoms during sex UuyvZf3kfOxHV9FQ

(does/doesn’t) reduce the risk of getting HIV and wfuE7iNURTJ/Smlg

(does/doesn’t) fully protect against skin-

Question

ziA/4MeCS0rpFEuHXJAgTjZSKlGDjrtTN+0r/mRym71iUOupTJv5h0u/Wl4dwQ7inbNRy1GzZtXcbItekg2+GFDLxHFp1LyAe5sO35A2B/67c/dZGYb+2xCXiwOEBnO9aj6EeGDNeTDmwWio2sD2psTOnv70eimBPmwyhl7+Odo+OGSjG/I8mXbulcIWG6zxcMK3Fkg5mhRL4ynYZxYJ21sCruBhbzFafpUDU+SPuwzH0ETMCM5cqEHKwwYOM88Q+OGDEByNLexxEddH9eGSVXf2qrwZi2VNjIat5N+MGVXdYFHrjp1sm29qYU7lwdtHQuestion

OdqHda9mTfhQItLaXKPV5xPsKCAerwQpRTbALGDo7bJFPUcWS7aOnIOmvdC9xZGCDH3OzPPtQ51qJ/eneRWCV5Iu+EWtXG3hXPQ+AFxRIwe8/z/DvRhqBmn5IgYSp6eznsPAbO/3I+yV43H0swBI43xEnlT1SF7klzh1Rnz67K9K+YEZoVewD5nT92U=Researchers have found no evidence that any environmental factor (parental relationships, childhood experiences, peer relationships, or dating experiences) influences the development of our sexual orientation.

Affiliation and Achievement

Affiliation and Achievement

Question

W9Mi/kr5GBMUYxV2SKn9oad7Cq8tMdEHYgorITqbxs38s1WWOXOy78T+AH8CKUSp+fyk/WWo0rLW8wRGim86qVM+iunI8WOLde8+RICkEEGfJtVhsKbwpLrbNf913oDbYNZmRju3DUR/sWNYbLTHB615d1jT/dNp+mtMWVtKquaNV21VcpXGzK7lBM0W75Su/COlMiMulG47cv7cQoRHn/VMxlm2ZAe5Eg70L0T/BNx/N58NsUHsRt0ziQbsqnGaXoAPpqy3ldXnB5HzMEqu4XAlYhjF2nxHhuxthGJqDRN5o0Xgq3O+fKx/XqWNk2ayuJJ8ET3DOjKwSet07cTLFFtr4OWtCp6w8jsoBZA+BmwIYhF/tKTp4WsMDD31wv2Ltag5l1frtJdyKujJY+AeCpkYQBwy0OYVKt0tqWlhzuY/fY8A959zscHLs3ZJMYI3KKlQH+EB2q3dHNhon6OUChPhq15dSEc6KXv4gJYlfynsvb2XX9lqBGGDtQGG1ROU2d1x2CwGXIR6IffMwrGA11YJATUe4axKH3/cNgp5Fzz04qzFIc2dzqgglhIRYC3bOJgpNPvWVneFQhVbQi9Li7eFiBWRAm/nanbtPimeGGs7A9d+sc4NdTylAuLXrjv3su4pT/5PIODtXBA2JsLXn5S3rqodKcfEVjAbBUp7y8znZI/uCUky4+emANzUA/xaS1Zf5BJadIDDMtwXOYfvSjoC6gGEh7c8wMT63rFP0k7gyvn335qS9NINV36x9q3pTY8P7WWaF/f5y4Nf/Idcmxyevng=Question

2hRaUSfCpwdljaY6ygi6/ei+xNKo7gNJV0r7MsL50MzB2Yg1tkqLssg6HmhOU6Heh66mJKAvPieja7uugbTqsY5irJN91vfMuudnMthW8cOmNXLLBnGBxECIfe/g98I/Monitor the time spent online, as well as our feelings about that time. Hide distracting online friends. Turn off or put away distracting devices. Consider a social networking fast, and get outside and away from technology regularly.