12.1 Introduction to Emotion

Please continue to the next section.

Emotion: Arousal, Behavior, and Cognition

12-

As my [DM’S] panicked search for Peter illustrates, emotions are a mix of

- bodily arousal (heart pounding).

- expressive behaviors (quickened pace).

- conscious experience, including thoughts (“Is this a kidnapping?”) and feelings (panic, fear, joy).

emotion a response of the whole organism, involving (1) physiological arousal, (2) expressive behaviors, and (3) conscious experience.

Not only emotion, but most psychological phenomena (vision, sleep, memory, sex, and so forth) can be approached these three ways—physiologically, behaviorally, and cognitively.

The puzzle for psychologists is figuring out how these three pieces fit together. To do that, we need answers to two big questions:

- A chicken-and-egg debate: Does your bodily arousal come before or after your emotional feelings? (Did I first notice my racing heart and faster step, and then feel terror about losing Peter? Or did my sense of fear come first, stirring my heart and legs to respond?)

- How do thinking (cognition) and feeling interact? Does cognition always come before emotion? (Did I think about a kidnapping threat before I reacted emotionally?)

Historical emotion theories, as well as current research, have sought to answer these questions.

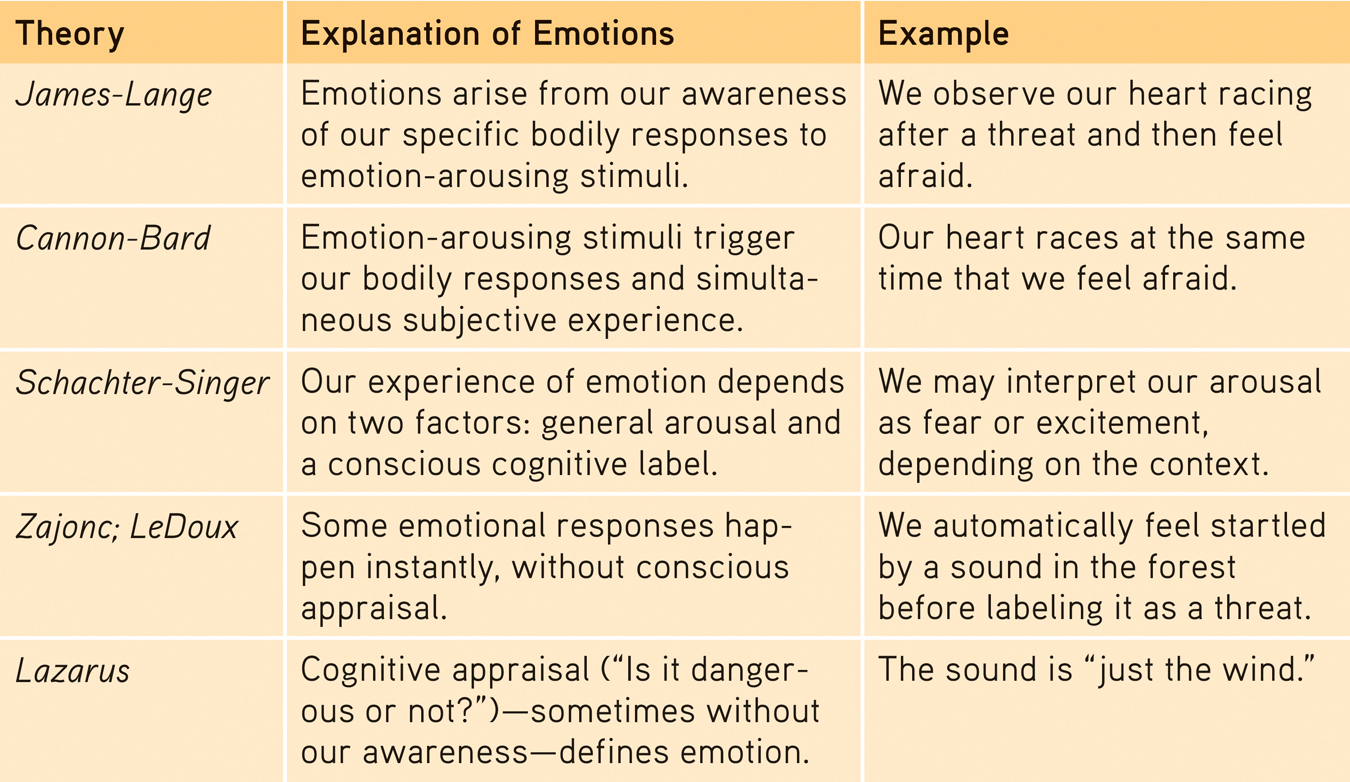

James-Lange theory the theory that our experience of emotion is our awareness of our physiological responses to emotion-arousing stimuli.

Historical Emotion Theories

Cannon-Bard theory the theory that an emotion-arousing stimulus simultaneously triggers (1) physiological responses and (2) the subjective experience of emotion.

James-

Cannon-

If our bodily responses and emotional experiences occur simultaneously and one does not affect the other, as Cannon and Bard believed, then people who suffer spinal cord injuries should not notice a difference in their experience of emotion after the injury. But there are differences, according to one study of 25 World War II soldiers (Hohmann, 1966). Those with lower-

461

But most researchers now agree that our emotions also involve cognition (Averill, 1993; Barrett, 2006). Whether we fear the man behind us on the dark street depends entirely on whether we interpret his actions as threatening or friendly.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to the Cannon-Bard theory, (a) our physiological response to a stimulus (for example, a pounding heart), and (b) the emotion we experience (for example, fear) occur ______________ (simultaneously/sequentially). According to the James-Lange theory, (a) and (b) occur ______________ (simultaneously/sequentially).

simultaneously; sequentially (first the physiological response, and then the experienced emotion)

Schachter and Singer Two-

two-factor theory the Schachter-Singer theory that to experience emotion one must (1) be physically aroused and (2) cognitively label the arousal.

12-

Stanley Schachter and Jerome Singer (1962) believed that an emotional experience requires a conscious interpretation of arousal: Our physical reactions and our thoughts (perceptions, memories, and interpretations) together create emotion. In their two-factor theory, emotions therefore have two ingredients: physical arousal and cognitive appraisal.

Consider how arousal spills over from one event to the next. Imagine arriving home after an invigorating run and finding a message that you got a longed-

To explore this spillover effect, Schachter and Singer injected college men with the hormone epinephrine, which triggers feelings of arousal. Picture yourself as a participant: After receiving the injection, you go to a waiting room, where you find yourself with another person (actually an accomplice of the experimenters) who is acting either euphoric or irritated. As you observe this person, you begin to feel your heart race, your body flush, and your breathing become more rapid. If you had been told to expect these effects from the injection, what would you feel? The actual volunteers felt little emotion—

This discovery—

The point to remember: Arousal fuels emotion; cognition channels it.

462

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation.

For a 4-minute demonstration of the relationship between arousal and cognition, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotion = Arousal Plus Interpretation.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- According to Schachter and Singer, two factors lead to our experience of an emotion: (1) physiological arousal and (2) ______________ appraisal.

cognitive

Zajonc, LeDoux, and Lazarus: Does Cognition Always Precede Emotion?

But is the heart always subject to the mind? Must we always interpret our arousal before we can experience an emotion? Robert Zajonc (1923–

For example, when people repeatedly view stimuli flashed too briefly for them to interpret, they come to prefer those stimuli. Unaware of having previously seen them, they nevertheless like them. We have an acutely sensitive automatic radar for emotionally significant information, such that even a subliminally flashed stimulus can prime us to feel better or worse about a follow-

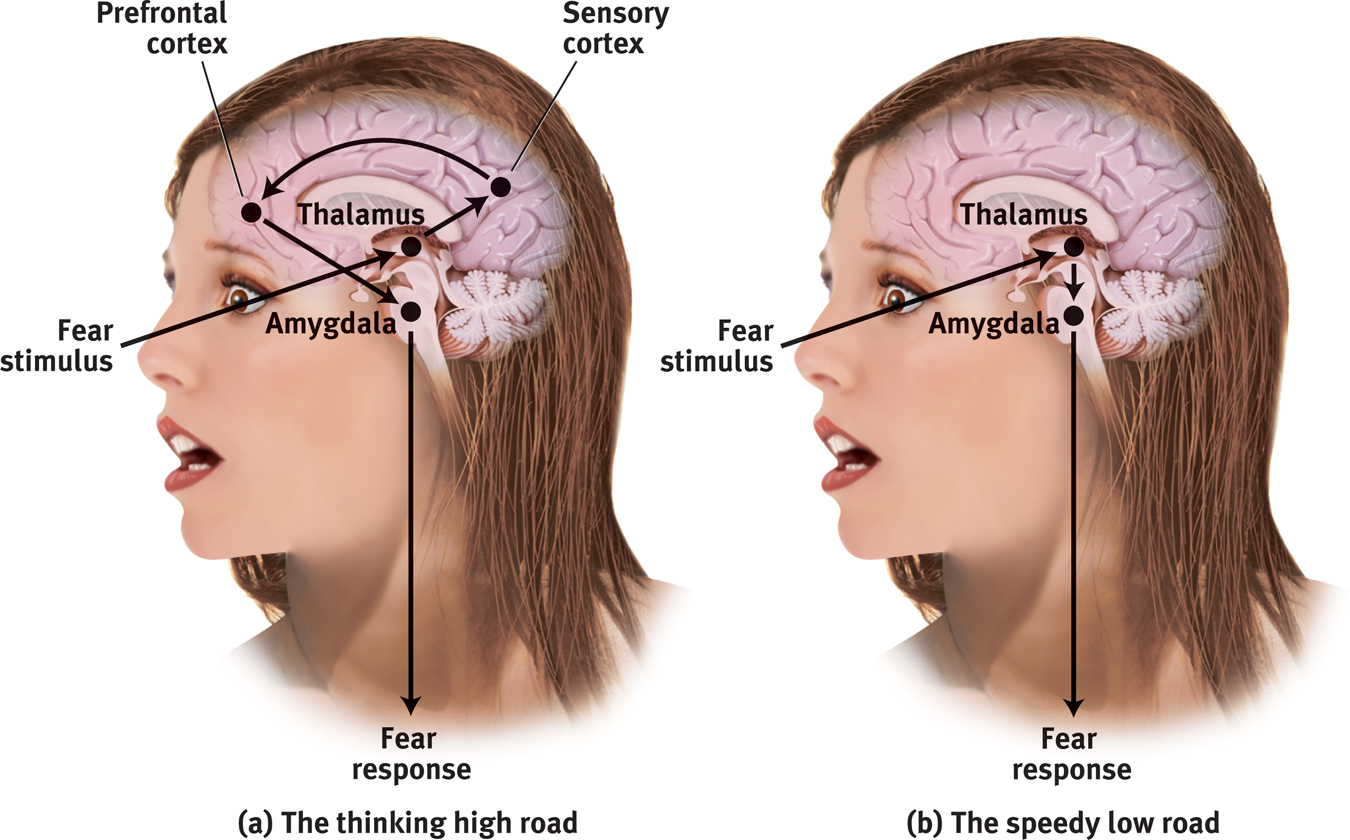

Neuroscientists are charting the neural pathways of emotions (Ochsner et al., 2009). Our emotional responses can follow two different brain pathways. Some emotions (especially more complex feelings like hatred and love) travel a “high road.” A stimulus following this path would travel (by way of the thalamus) to the brain’s cortex (FIGURE 12.1a). There, it would be analyzed and labeled before the response command is sent out, via the amygdala (an emotion-

Figure 12.1

Figure 12.1The brain’s pathways for emotions In the two-

But sometimes our emotions (especially simple likes, dislikes, and fears) take what Joseph LeDoux (2002) has called the “low road,” a neural shortcut that bypasses the cortex. Following the low road, a fear-

463

The amygdala sends more neural projections up to the cortex than it receives back, which makes it easier for our feelings to hijack our thinking than for our thinking to rule our feelings (LeDoux & Armony, 1999). Thus, in the forest, we can jump at the sound of rustling bushes nearby, leaving it to our cortex to decide later whether the sound was made by a snake or by the wind. Such experiences support Zajonc’s belief that some of our emotional reactions involve no deliberate thinking.

Emotion researcher Richard Lazarus (1991, 1998) conceded that our brain processes vast amounts of information without our conscious awareness, and that some emotional responses do not require conscious thinking. Much of our emotional life operates via the automatic, speedy low road. But, he asked, how would we know what we are reacting to if we did not in some way appraise the situation? The appraisal may be effortless and we may not be conscious of it, but it is still a mental function. To know whether a stimulus is good or bad, the brain must have some idea of what it is (Storbeck et al., 2006). Thus, said Lazarus, emotions arise when we appraise an event as harmless or dangerous, whether we truly know it is or not. We appraise the sound of the rustling bushes as the presence of a threat. Later, we realize that it was “just the wind.”

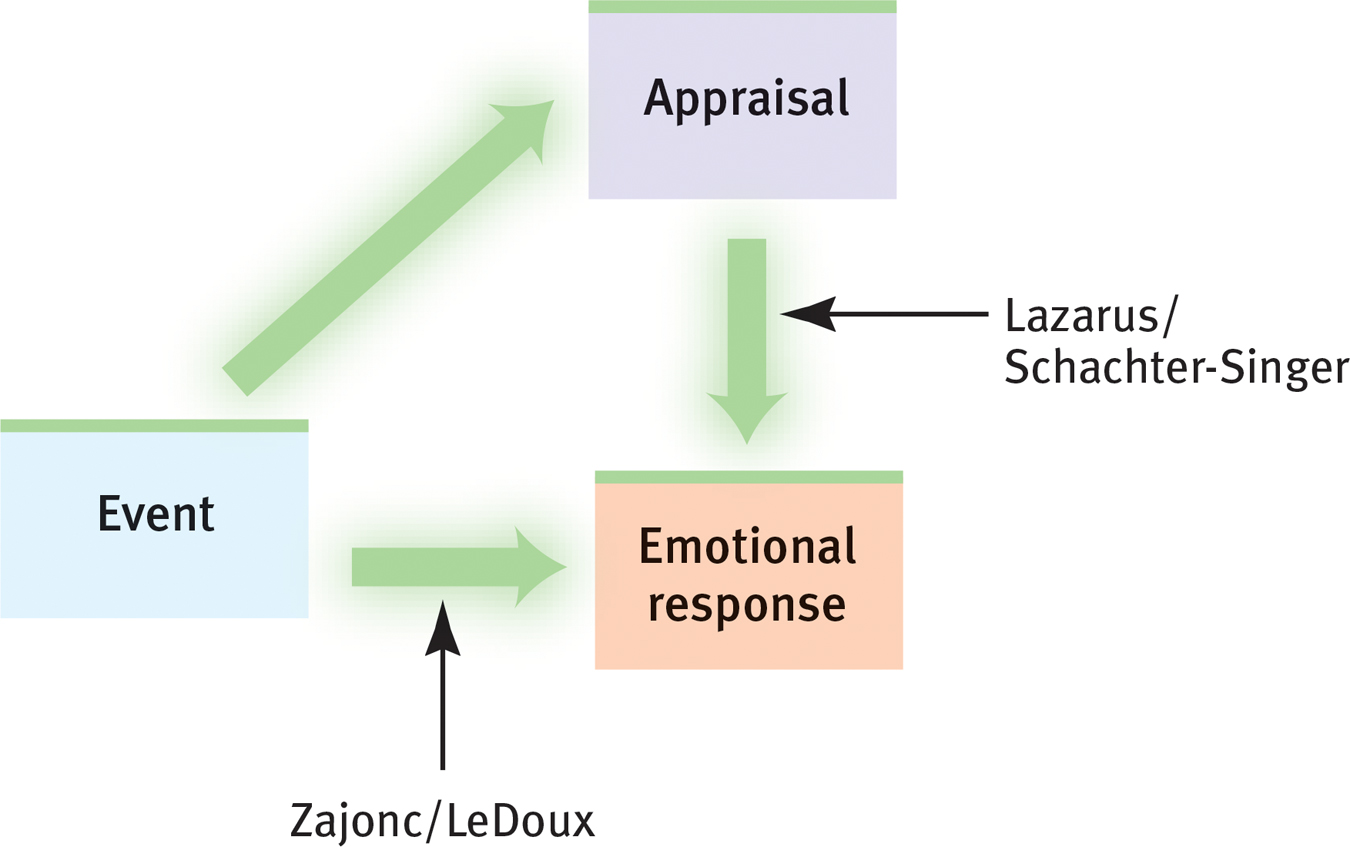

So, as Zajonc and LeDoux have demonstrated, some emotional responses—

Figure 12.2

Figure 12.2Two pathways for emotions Zajonc and LeDoux emphasized that some emotional responses are immediate, before any conscious appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized that our appraisal and labeling of events also determine our emotional responses.

But our feelings about politics are also subject to our memories, expectations, and interpretations, as Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer might have predicted. Moreover, highly emotional people are intense partly because of their interpretations. They may personalize events as being somehow directed at them, and they may generalize their experiences by blowing single incidents out of proportion (Larsen & Diener, 1987). Thus, learning to think more positively can help people feel better. Although the emotional low road functions automatically, the thinking high road allows us to retake some control over our emotional life. Together, automatic emotion and conscious thinking weave the fabric of our emotional lives. (TABLE 12.1 below summarizes these emotion theories.)

Table 12.1

Table 12.1Summary of Emotion Theories

464

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Emotion researchers have disagreed about whether emotional responses occur in the absence of cognitive processing. How would you characterize the approach of each of the following researchers: Zajonc, LeDoux, Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer?

Zajonc and LeDoux suggested that we experience some emotions without any conscious, cognitive appraisal. Lazarus, Schachter, and Singer emphasized the importance of appraisal and cognitive labeling in our experience of emotion.

Embodied Emotion

Whether you are falling in love or grieving a death, you need little convincing that emotions involve the body. Feeling without a body is like breathing without lungs. Some physical responses are easy to notice. Other emotional responses we experience without awareness.

Emotions and the Autonomic Nervous System

12-

“Fear lends wings to his feet.”

Virgil, Aeneid, 19 b.c.e.

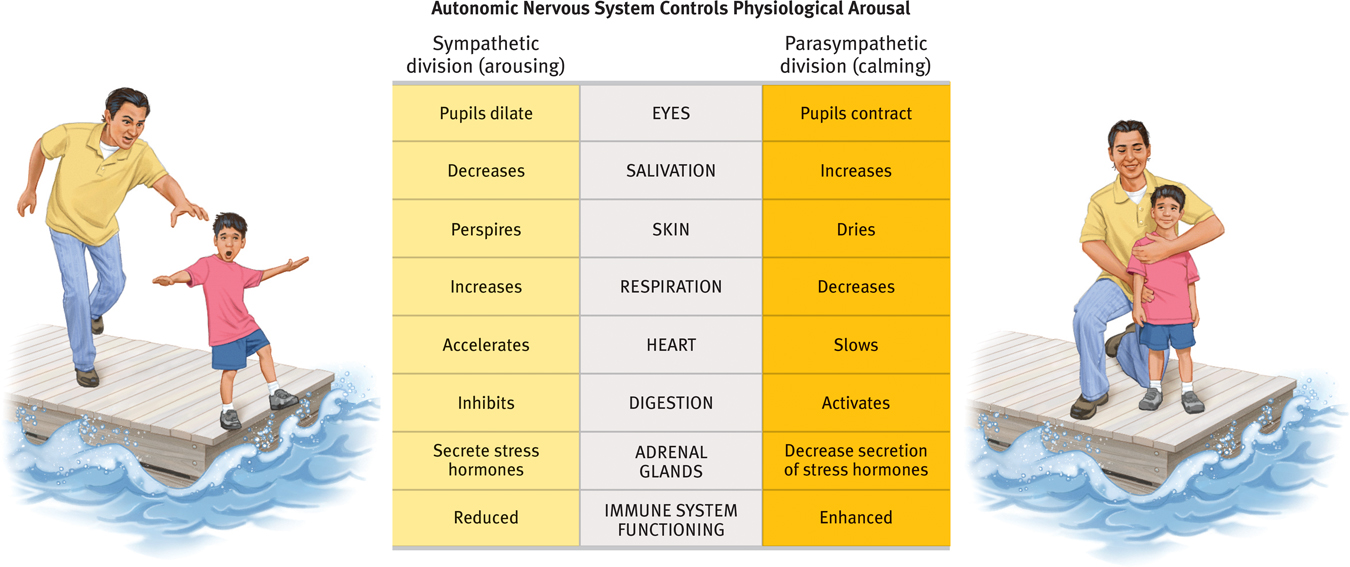

In a crisis, the sympathetic division of your autonomic nervous system (ANS) mobilizes your body for action (FIGURE 12.3). It directs your adrenal glands to release the stress hormones epinephrine (adrenaline) and norepinephrine (noradrenaline). To provide energy, your liver pours extra sugar into your bloodstream. To help burn the sugar, your respiration increases to supply needed oxygen. Your heart rate and blood pressure increase. Your digestion slows, diverting blood from your internal organs to your muscles. With blood sugar driven into the large muscles, running becomes easier. Your pupils dilate, letting in more light. To cool your stirred-

Figure 12.3

Figure 12.3Emotional arousal Like a crisis control center, the autonomic nervous system arouses the body in a crisis and calms it when danger passes.

According to the Yerkes-

465

When the crisis passes, the parasympathetic division of your ANS gradually calms your body, as stress hormones slowly leave your bloodstream. After your next crisis, think of this: Without any conscious effort, your body’s response to danger is wonderfully coordinated and adaptive—

The Physiology of Emotions

12-

Imagine conducting an experiment measuring the physiological responses of emotion. In each of four rooms, you have someone watching a movie: In the first, the person is viewing a horror show; in the second, an anger-

466

With training, you could probably pick out the bored viewer. But discerning physiological differences among fear, anger, and sexual arousal is much more difficult (Barrett, 2006). Different emotions can share common biological signatures.

A single brain region can also serve as the seat of seemingly different emotions. Consider the broad emotional portfolio of the insula, a neural center deep inside the brain. The insula is activated when we experience various negative social emotions, such as lust, pride, and disgust. In brain scans, it becomes active when people bite into some disgusting food, smell the same disgusting food, think about biting into a disgusting cockroach, or feel moral disgust over a sleazy business exploiting a saintly widow (Sapolsky, 2010). Similar multitasking regions are found in other brains areas.

Yet our emotions—

“No one ever told me that grief felt so much like fear. I am not afraid, but the sensation is like being afraid. The same fluttering in the stomach, the same restlessness, the yawning. I keep on swallowing.”

C. S. Lewis, A Grief Observed, 1961

Some of our emotions also differ in their brain circuits (Panksepp, 2007). Observers watching fearful faces showed more amygdala activity than did other observers who watched angry faces (Whalen et al., 2001). Brain scans and EEG recordings show that emotions also activate different areas of the brain’s cortex. When you experience negative emotions such as disgust, your right prefrontal cortex tends to be more active than the left. Depression-

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

polygraph a machine, commonly used in attempts to detect lies, that measures several of the physiological responses (such as perspiration and cardiovascular and breathing changes) accompanying emotion.

Lie Detection

12-

Can a lie detector—a polygraph—reveal lies? Polygraphs don’t literally detect lies. Instead, they measure emotion-

Critics point out two problems: First, our physiological arousal is much the same from one emotion to another. Anxiety, irritation, and guilt all prompt similar physiological reactivity. Second, many innocent people respond with heightened tension to the accusations implied by the critical questions (FIGURE 12.4). Many rape victims, for example, have “failed” these tests when reacting emotionally but truthfully (Lykken, 1991).

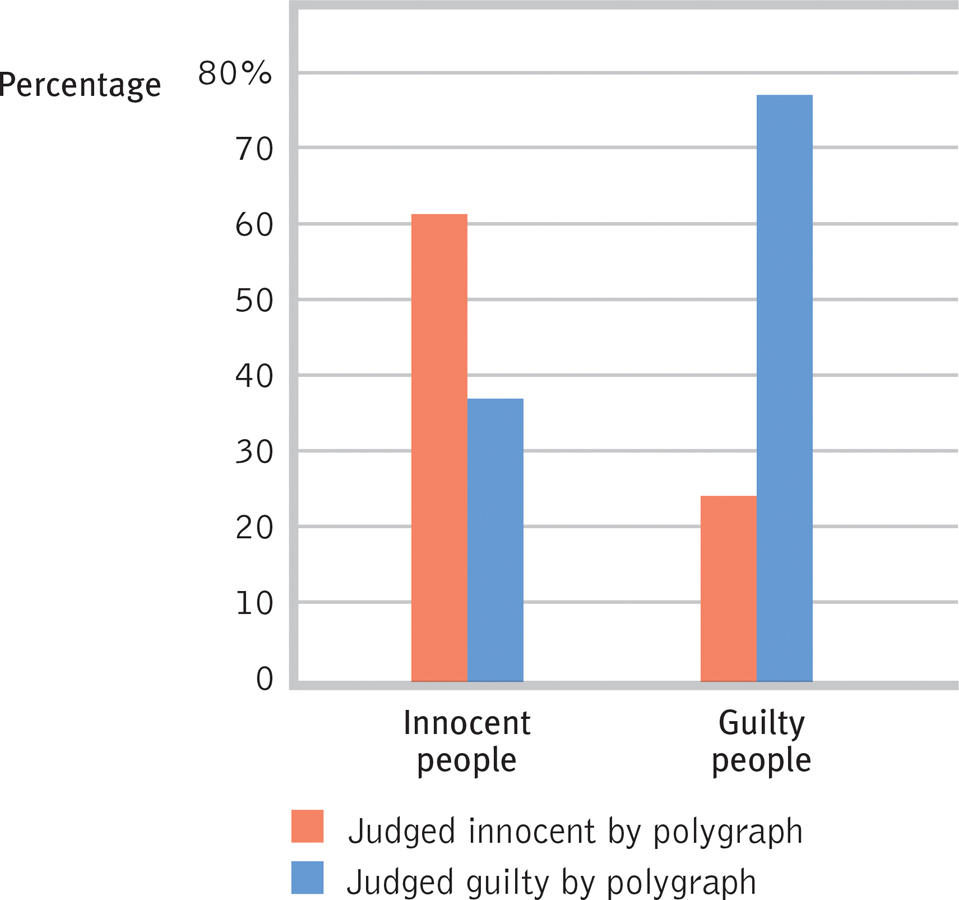

Figure 12.4

Figure 12.4How often do lie detection tests lie? In one study, polygraph experts interpreted the polygraph data of 100 people who had been suspects in theft crimes (Kleinmuntz & Szucko, 1984). Half the suspects were guilty and had confessed; the other half had been proven innocent. Had the polygraph experts been the judges, more than one-

A 2002 U.S. National Academy of Sciences report noted that “no spy has ever been caught [by] using the polygraph.” It is not for lack of trying. The FBI, CIA, and U.S. Departments of Defense and Energy have tested tens of thousands of employees, and polygraph use in Europe has also increased (Meijer & Verschuere, 2010). Yet Aldrich Ames, a Russian spy within the CIA, went undetected. Ames took many “polygraph tests and passed them all,” noted Robert Park (1999). “Nobody thought to investigate the source of his sudden wealth—

A more effective lie detection approach uses a guilty knowledge test, which assesses a suspect’s physiological responses to crime-

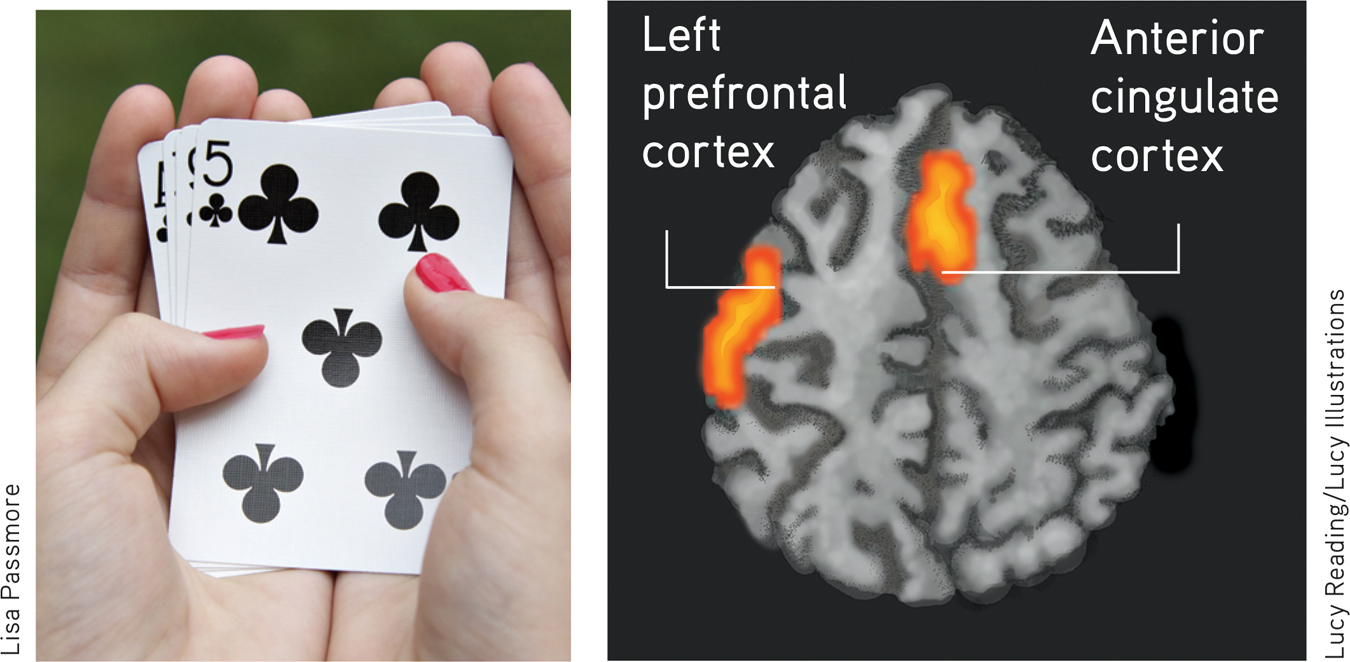

Research teams are now exploring new ways to nab liars. “Forensic neuroscience” researchers are going straight to the seat of deceit—

Figure 12.5

Figure 12.5Liar, liar, brain’s on fire An fMRI scan identified two brain areas that became especially active when a participant lied about holding a five of clubs. (fMRI scan from Langleben et al., 2002.)

467

Positive moods tend to trigger more left frontal lobe activity. People with positive personalities—

To sum up, we can’t easily see differences in emotions from tracking heart rate, breathing, and perspiration. But facial expressions and brain activity can vary with the emotion. So, do we, like Pinocchio, give off telltale signs when we lie? For more on that question, see Thinking Critically About: Lie Detection.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do the two divisions of the autonomic nervous system affect our emotional responses?

The sympathetic division of the ANS arouses us for more intense experiences of emotion, pumping out the stress hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine to prepare our body for fight or flight. The parasympathetic division of the ANS takes over when a crisis passes, restoring our body to a calm physiological and emotional state.

468

REVIEW: Introduction to Emotion

|

REVIEW | Introduction to Emotion |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

12-

Emotions are psychological responses of the whole organism involving an interplay among physiological arousal, expressive behaviors, and conscious experience.

Theories of emotion generally address two major questions: (1) Does physiological arousal come before or after emotional feelings, and (2) how do feeling and cognition interact? The James-Lange theory maintains that emotional feelings follow our body’s response to emotion-inducing stimuli. The Cannon-Bard theory proposes that our physiological response to an emotion-inducing stimulus occurs at the same time as our subjective feeling of the emotion (one does not cause the other).

12-

The Schachter-Singer two-factor theory holds that our emotions have two ingredients, physical arousal and a cognitive label, and the cognitive labels we put on our states of arousal are an essential ingredient of emotion. Lazarus agreed that many important emotions arise from our interpretations or inferences. Zajonc and LeDoux, however, believe that some simple emotional responses occur instantly, not only outside our conscious awareness, but before any cognitive processing occurs. This interplay between emotion and cognition illustrates our dual-track mind.

12-

The arousal component of emotion is regulated by the autonomic nervous system’s sympathetic (arousing) and parasympathetic (calming) divisions. In a crisis, the fight-or-flight response automatically mobilized your body for action.

Arousal affects performance in different ways, depending on the task. Performance peaks at lower levels of arousal for difficult tasks, and at higher levels for easy or well-learned tasks.

12-

Emotions may be similarly arousing, but some subtle physiological responses, such as facial muscle movements, distinguish them. More meaningful differences have been found in activity in some brain pathways and cortical areas.

12-

Polygraphs, which measure several physiological indicators of emotion, are not accurate enough to justify widespread use in business and law enforcement. The use of guilty knowledge questions and new forms of technology may produce better indications of lying.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

9tH5kpirr0UQkqyJ/Xl97GkglWb+vR4xZGd1+Ta/6clC9Ax54NYWI0vMoH5mmmF+VexjTkT+26RBHvqqsMcyzA8dSP12JxGPfTkme//vrkRJZPYuH+mRiYqpkHgSnF0eWt7UZT6znDXtSDjgFHQH5yNMK64h7UfbyKyu33aiyYTGcGzVZgYSiwI7tZIY+Gg+IOM8dtn/GYpv0P9+k+Agbh6jvXT08rtD53NAEyQSdCv4P2/TMDAOMEY4LCaXnAfrNs5y4XULMoyBOqo9K4TbNLJ950VqwNjAt1xgebkcndjZ7v3vTk0xTD4n4M0K0mSM9wT++Y1lAx8HPDvNbSvBoy42x1OfOqfCR3KWz3dKYCqf8j+jm5z5LSsWRozWYM6nZWTd87HOI6ncE7Q5dNPdAS7I5a7QGwBCS9PsWQxqr0u8Bt+eRCELJGmEwhbqW2pVR4X6j94/jn+vngervGEEUIaxhJxcSII4BFcVHlK6zjFsHZ1fOXXTwlCh00aQk0capI+KQ9Z/gMLcehOu3w0P32k0HuVADURE0K0aUi+l3Q9oOdAYYbWddql3ofC3eYJRz//0A6zC+q1whwHBKfdCu2aBo+rtpjGMmlz8fd1CntwkpvFcKd26qKw12OJ9evuUmWzSetAKjCvKu8PAOS8SHcIpNi3oGnq7pu94XM87+gwfacgqRV9+C5EyUpehVPD2NTBmkYykJn8qplf8L/zS1qiTvhEzx7Ni3LoSWyNfj2XTHfrDTX21lvvPouJqOqt08Lu0Y27Nhp9pfc2yJ+SSJmkA/30gQdk3ka3EwQfQcYy1lQR7nHZHrqE07WLNjBpkgFQ5zkcjGMkXZMgjGXiRJ1Kg23HwZodWjoBis3Wvj/T0wiVjEKLIG89wleA/UdKX1JgI5h6gufXjqynGjo+IG/UzO/CTEjh4K79bYTYZ+pBXsR05Ts5NIaX1oMiw4d1Xw0e9Nhi3q3l0/zlWfxi7U7sQua4Zy37zbF2YCGWpv9o8xO7Sr83V8ykyw0QuWvD0o1Y/soPNoLdiKduHbAoOph79OHF/P0P0LsVNDEqJFRI7mBTnUse  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.