13.1 Social Thinking

social psychology the scientific study of how we think about, influence, and relate to one another.

13-

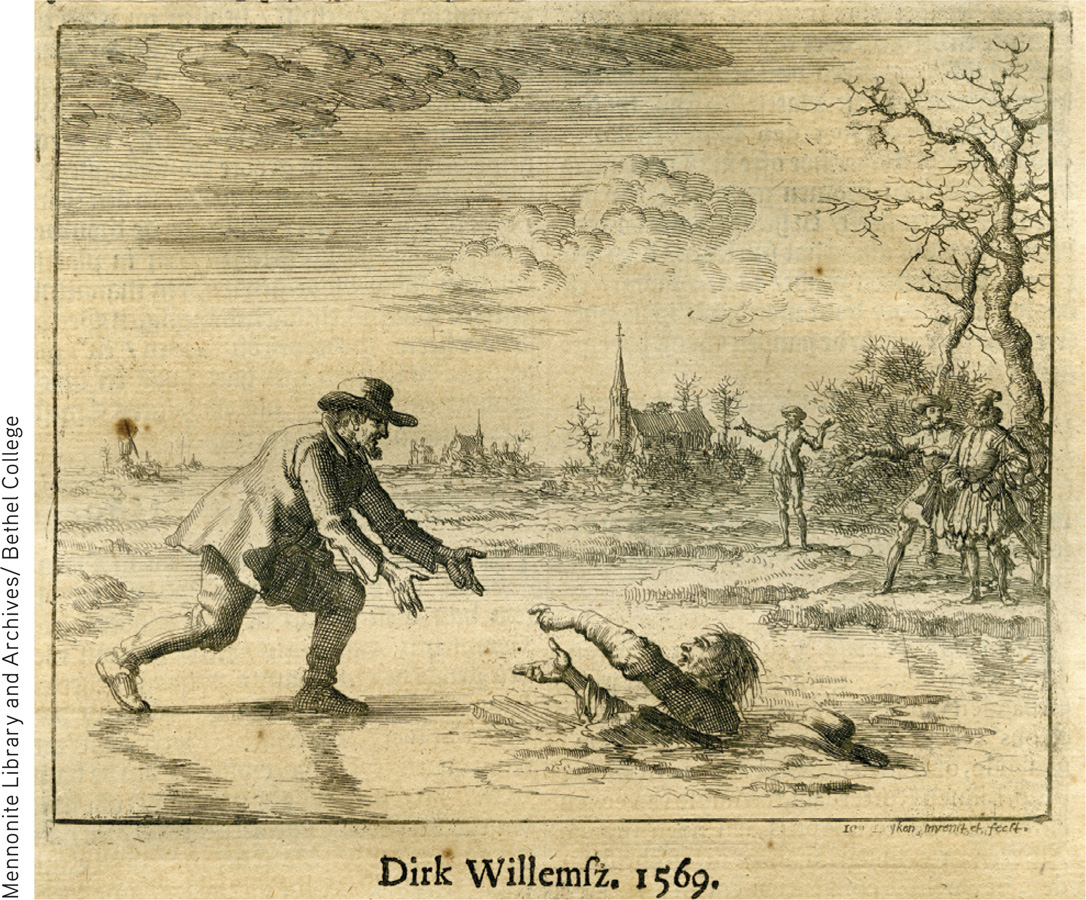

Personality psychologists focus on the person. They study the personal traits and dynamics that explain why different people may act differently in a given situation, such as the one Willems faced. (Would you have helped the jailer out of the icy water?) Social psychologists focus on the situation. They study the social influences that explain why the same person will act differently in different situations. Might the jailer have acted differently—

The Fundamental Attribution Error

attribution theory the theory that we explain someone’s behavior by crediting either the situation or the person’s disposition.

fundamental attribution error the tendency for observers, when analyzing others’ behavior, to underestimate the impact of the situation and to overestimate the impact of personal disposition.

Our social behavior arises from our social cognition. Especially when the unexpected occurs, we want to understand and explain why people act as they do. After studying how people explain others’ behavior, Fritz Heider (1958) proposed an attribution theory: We can attribute the behavior to the person’s stable, enduring traits (a dispositional attribution), or we can attribute it to the situation (a situational attribution).

For example, in class, we notice that Juliette seldom talks. Over coffee, Jack talks nonstop. That must be the sort of people they are, we decide. Juliette must be shy and Jack outgoing. Such attributions—

David Napolitan and George Goethals (1979) demonstrated the fundamental attribution error in an experiment with Williams College students. They had students talk, one at a time, with a young woman who acted either cold and critical or warm and friendly. Before the conversations, the researchers told half the students that the woman’s behavior would be spontaneous. They told the other half the truth—

Did hearing the truth affect students’ impressions of the woman? Not at all! If the woman acted friendly, both groups decided she really was a warm person. If she acted unfriendly, both decided she really was a cold person. They attributed her behavior to her personal disposition even when told that her behavior was situational—that she was merely acting that way for the purposes of the experiment.

What Factors Affect Our Attributions?

The fundamental attribution error appears more often in some cultures than in others. Individualist Westerners more often attribute behavior to people’s personal traits. People in East Asian cultures are somewhat more sensitive to the power of the situation (Heine & Ruby, 2010; Kitayama et al., 2009). This difference has appeared in experiments that asked people to view scenes, such as a big fish swimming. Americans focused more on the individual fish, and Japanese people more on the whole scene (Chua et al., 2005; Nisbett, 2003).

We all commit the fundamental attribution error. Consider: Is your psychology instructor shy or outgoing?

If you answer “outgoing,” remember that you know your instructor from one situation—

519

When we explain our own behavior, we are sensitive to how behavior changes with the situation (Idson & Mischel, 2001). (An important exception: We more often attribute our intentional and admirable actions not to situations but to our own good reasons [Malle, 2006; Malle et al., 2007].) We also are sensitive to the power of the situation when we explain the behavior of people we know well and have seen in different contexts. We more often commit the fundamental attribution error when a stranger acts badly. Having only seen that red-

As we act, our eyes look outward; we see others’ faces, not our own. If we could take an observer’s point of view, would we become more aware of our own personal style? To test this idea, researchers have filmed two people interacting with a camera behind each person. Then they showed each person a replay of their interaction—

What Are the Consequences of Our Attributions?

Some 7 in 10 college women report having experienced a man misattributing her friendliness as a sexual come-on (Jacques-Tiura et al., 2007).

The way we explain others’ actions, attributing them to the person or the situation, can have important real-

Finally, consider the social and economic effects of attribution. How do we explain poverty or unemployment? In Britain, India, Australia, and the United States (Furnham, 1982; Pandey et al., 1982; Wagstaff, 1982; Zucker & Weiner, 1993), political conservatives have tended to place the blame on the personal dispositions of the poor and unemployed: “People generally get what they deserve. Those who don’t work are freeloaders. Those who take initiative can still get ahead.” After inviting people to reflect on the power of choice—

The point to remember: Our attributions—

520

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.

Attitudes and Actions

attitude feelings, often influenced by our beliefs, that predispose us to respond in a particular way to objects, people, and events.

13-

Attitudes are feelings, often influenced by our beliefs, that predispose our reactions to objects, people, and events. If we believe someone is threatening us, we may feel fear and anger toward the person and act defensively. The traffic between our attitudes and our actions is two-

Attitudes Affect Actions

Consider the climate-

Knowing that public attitudes affect public policies, activists on both sides are aiming to persuade. Persuasion efforts generally take two forms:

- Peripheral route persuasion doesn’t engage systematic thinking, but does produce fast results as people respond to uninformative cues (such as celebrity endorsements) and make snap judgments. A trusted politician may declare climate change a hoax. A perfume ad may lure us with images of beautiful or famous people in love.

- Central route persuasion offers evidence and arguments that aim to trigger favorable thoughts. It occurs mostly when people are naturally analytical or involved in the issue. Climate scientists marshal evidence of climate warming. An automotive ad may itemize a car’s great features. Because it is more thoughtful and less superficial, it is more durable.

peripheral route persuasion occurs when people are influenced by incidental cues, such as a speaker’s attractiveness.

central route persuasion occurs when interested people focus on the arguments and respond with favorable thoughts.

Persuaders try to influence our behavior by changing our attitudes. But other factors, including the situation, also influence our behavior. Strong social pressures, for example, can weaken the attitude-

Attitudes are especially likely to affect behavior when external influences are minimal, and when the attitude is stable, specific to the behavior, and easily recalled (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006). One experiment used vivid, easily recalled information to persuade people that sustained tanning put them at risk for future skin cancer. One month later, 72 percent of the participants, and only 16 percent of those in a waitlist control group, had lighter skin (McClendon & Prentice-

Actions Affect Attitudes

Now consider a more surprising principle: Not only will people stand up for what they believe, they also will more strongly believe in what they have stood up for. Many streams of evidence confirm that attitudes follow behavior (FIGURE 13.1).

Figure 13.1

Figure 13.1Attitudes follow behavior Cooperative actions, such as those performed by people on sports teams (including Germany, shown here celebrating their World Cup 2014 victory), feed mutual liking. Such attitudes, in turn, promote positive behavior.

521

foot-in-the-door phenomenon the tendency for people who have first agreed to a small request to comply later with a larger request.

The Foot-

How did the Chinese captors achieve these amazing results? A key ingredient was their effective use of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon: They knew that people who agreed to a small request would find it easier to comply later with a larger one. The Chinese began with harmless requests, such as copying a trivial statement, but gradually escalated their demands (Schein, 1956). The next statement to be copied might list flaws of capitalism. Then, to gain privileges, the prisoners participated in group discussions, wrote self-

In dozens of experiments, researchers have coaxed people into acting against their attitudes or violating their moral standards, with the same result: Doing becomes believing. After giving in to a request to harm an innocent victim—

“If the King destroys a man, that’s proof to the King it must have been a bad man.”

Thomas Cromwell, in Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, 1960

Fortunately, the attitudes-

522

role a set of expectations (norms) about a social position, defining how those in the position ought to behave.

Racial attitudes likewise follow behavior. In the years immediately following the introduction of school desegregation in the United States and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, White Americans expressed diminishing racial prejudice. And as Americans in different regions came to act more alike—

“Fake it until you make it.”

Alcoholics Anonymous saying

Role Playing Affects Attitudes When you adopt a new role—when you become a college student, marry, or begin a new job—

To view Philip Zimbardo’s 14-minute illustration and explanation of his famous prison simulation, visit the LaunchPad Video—The Stanford Prison Study: The Power of the Situation.

To view Philip Zimbardo’s 14-minute illustration and explanation of his famous prison simulation, visit the LaunchPad Video—The Stanford Prison Study: The Power of the Situation.

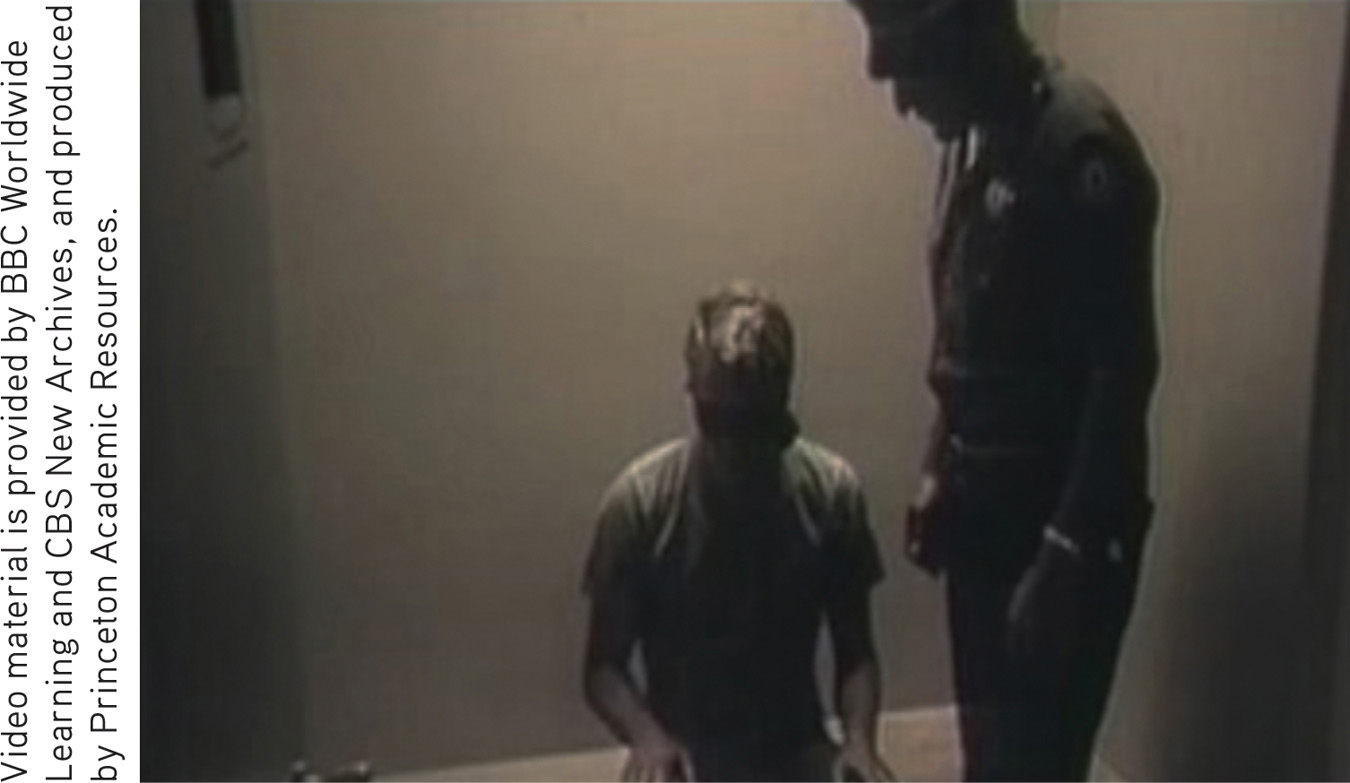

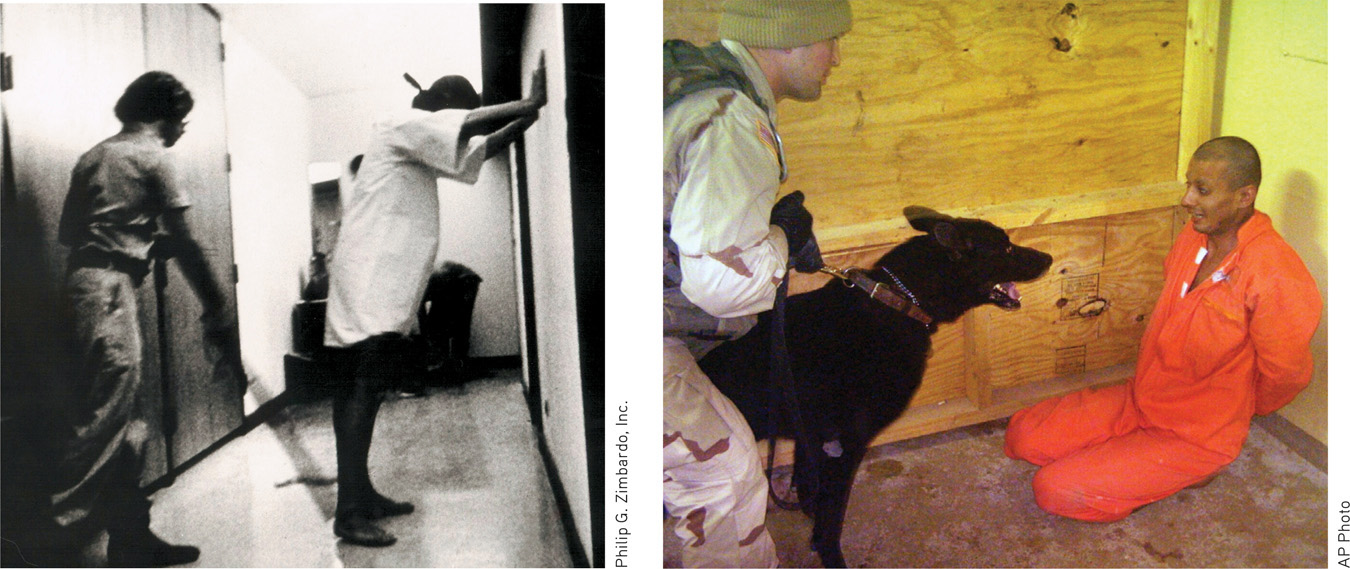

Role playing morphed into real life in one famous and controversial study in which male college students volunteered to spend time in a simulated prison. Stanford psychologist Philip Zimbardo (1972) randomly assigned some volunteers to be guards. He gave them uniforms, clubs, and whistles and instructed them to enforce certain rules. Others became prisoners, locked in barren cells and forced to wear humiliating outfits. For a day or two, the volunteers self-

Critics question the reliability of Zimbardo’s results (Griggs, 2014). But this much seems true: Role playing can train torturers (Staub, 1989). In the early 1970s, the Greek military government eased men into their roles. First, a trainee stood guard outside an interrogation cell. After this “foot in the door” step, he stood guard inside. Only then was he ready to become actively involved in the questioning and torture. What we do, we gradually become. In one study of German males, military training toughened their personalities, leaving them less agreeable even five years later after leaving the military (Jackson et al., 2012). And it’s true of us all: Every time we act like the people around us we slightly change ourselves to be more like them, and less like who we used to be.

Yet people differ. In Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison simulation and in other atrocity-

cognitive dissonance theory the theory that we act to reduce the discomfort (dissonance) we feel when two of our thoughts (cognitions) are inconsistent. For example, when we become aware that our attitudes and our actions clash, we can reduce the resulting dissonance by changing our attitudes.

523

Cognitive Dissonance: Relief From Tension So far, we have seen that actions can affect attitudes, sometimes turning prisoners into collaborators, doubters into believers, and compliant guards into abusers. But why? One explanation is that when we become aware that our attitudes and actions don’t coincide, we experience tension, or cognitive dissonance. Indeed, the brain regions that become active when people experience cognitive conflict and negative arousal also become active when people experience cognitive dissonance (Kitayama et al., 2013). To relieve this tension, according to Leon Festinger’s (1957) cognitive dissonance theory, we often bring our attitudes into line with our actions.

To check your understanding of cognitive dissonance, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Cognitive Dissonance.

To check your understanding of cognitive dissonance, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Cognitive Dissonance.

Dozens of experiments have explored this cognitive dissonance phenomenon. Many have made people feel responsible for behavior that clashed with their attitudes and had foreseeable consequences. In one of these experiments, you might agree for a measly $2 to help a researcher by writing an essay that supports something you don’t believe in (perhaps a tuition increase). Feeling responsible for the statements (which are inconsistent with your attitudes), you would probably feel dissonance, especially if you thought an administrator would be reading your essay. To reduce the uncomfortable tension you might start believing your phony words. At such times, it’s as if we rationalize, “If I chose to do it (or say it), I must believe in it.” The less coerced and more responsible we feel for a troubling act, the more dissonance we feel. The more dissonance we feel, the more motivated we are to find consistency, such as changing our attitudes to help justify the act.

“Sit all day in a moping posture, sigh, and reply to everything with a dismal voice, and your melancholy lingers. … If we wish to conquer undesirable emotional tendencies in ourselves, we must … go through the outward movements of those contrary dispositions which we prefer to cultivate.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890

The attitudes-

The point to remember: Cruel acts shape the self. But so do acts of good will. Act as though you like someone, and you soon may. Changing our behavior can change how we think about others and how we feel about ourselves.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Driving to school one snowy day, Marco narrowly misses a car that slides through a red light. “Slow down! What a terrible driver,” he thinks to himself. Moments later, Marco himself slips through an intersection and yelps, “Wow! These roads are awful. The city plows need to get out here.” What social psychology principle has Marco just demonstrated? Explain.

By attributing the other person’s behavior to the person (“he’s a terrible driver”) and his own to the situation (“these roads are awful”), Marco has exhibited the fundamental attribution error.

- How do our attitudes and our actions affect each other?

Our attitudes often influence our actions as we behave in ways consistent with our beliefs. However, our attitudes also follow our actions; we come to believe in what we have done.

- When people act in a way that is not in keeping with their attitudes, and then change their attitudes to match those actions, ______________ ______________ theory attempts to explain why.

cognitive dissonance

524

REVIEW: Social Thinking

|

REVIEW | Social Thinking |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

13-

Social psychologists use scientific methods to study how people think about, influence, and relate to one another. They study the social influences that explain why the same person will act differently in different situations. When explaining others’ behavior, we may—especially if we come from an individualist Western culture—commit the fundamental attribution error, by underestimating the influence of the situation and overestimating the effects of stable, enduring traits. When explaining our own behavior, we more readily attribute it to the influence of the situation.

13-

Attitudes are feelings, often influenced by our beliefs, that predispose us to respond in certain ways. Peripheral route persuasion uses incidental cues (such as celebrity endorsement) to try to produce fast but relatively thoughtless changes in attitudes. Central route persuasion offers evidence and arguments to trigger thoughtful responses. When other influences are minimal, attitudes that are stable, specific, and easily recalled can affect our actions.

Actions can modify attitudes, as in the foot-in-the-door phenomenon (complying with a large request after having agreed to a small request) and role playing (acting a social part by following guidelines for expected behavior). When our attitudes don’t fit with our actions, cognitive dissonance theory suggests that we will reduce tension by changing our attitudes to match our actions.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

KoR9eV0OHi8NKWnQEuB3KFUBopu3UwEpwGKEkPhB/wu8mqO6pAiu7mFHFYlMAwHfOliP/NxS+40GEha/HxZGuMOrtbk1qVI43bRuleCp6TuMvFPBLjWEperJnEB8B8jUuGjfiZZeW8AWlaELN9mXaxglj7ZuUKO0aBxLYlFreywZ4NPP0Ge9JihsvGsqCougx7m6OMNILccdGEl4/VTm19le9GJ5PR4xgPdwmoAfuGwjHydgmFnex+RpJD8CrdBQx3Jlf+wozJn2Yg13v6ig8qHiN+6YqJkJLdBwxTPiw1Uym0CTgdhcW9tKrt0c0AOA1DnPdtrzTGBRlJh5/DqkPKEJ/mPU/FHwSidpiazMso6Q5LfAsgZWuBfb3BB6pz2Ha0vgYoBVXPe540RcpmY3KWJ3U6sBfR1U3dm3QllAIOjgG2eBjoCcLh6cQecg1pmw+BqAOlV1CLd7gabb84YXUgSmbyi4Iru6+NtFGntFGgO8vJPKbhWKd9N5pwfJMsOSklqP5e9vUyOL5cuDDpAArLKx9HIWBFonDOFqplPnQLIVeLsrJcs7iWGOw6eQrQ/iFjz/pEkx46bw/db3z/9BnL4RPoj2WDKXiBOmlJXWb70IRO2r2ZO/Ho2pux8/8j5geiEHmTieOMXXsRsjZyqFj25mIKsGqZhWx8ttiDuerHySxNFbJ45k2umsYDcCYSs2OKXeVUCYvxt0d7fwH0lp/r9f39ecCa2whLafI5KC/c92fcCa6c0Kse2xnTITqcxmMWDfl7dItKMaalSpovJVdQtzhwpp3G7yOJHF3Ene8iWcNEsgw0GV0DX2g8OqI2//+ImPouBRM+TmeV4IukRi/LPKXlBbRCmQd9M5a6YwNo6ZdPTpZ1o4i/SMGSBqUUxe5ro4RU+sl3acN1q5MmbJLFXbIJ+oU9Ix8gjMYg5kMz+Em+canopeQ9EcktDJgwI02LQXKry+7gv5bPJ1gkVVzbfXTERoeO/uo95aHeHoaEy2w4FtndPKn0QwDUH98qEO3GWEYW/POM2pd37nRx9wvl9RCFr6Q56Vw+W3Ch4dhC/iZg/0QAigBVIQNaf124GTRjXvBzJN1HShtimEZe1ECJTkVABRSkhtWCoIAiEwXpN4OgO9yDfOU91htWp8waRa7jXNqiiQfkUuk1yKS5RZl39AgV0ShAEAZuTQTWiASy+huEqRbrtg3A9rj0lUtkgDCajrFgzQmtBY/lXRHNZ9HSBg+rZCoAjvkSSVDAoyWTnkJf+ly2f4Fkqb14tRsFsJb0MN3NtVP0OM4jZEgvjKWrPZLOZipgl7ZojZcpqwUlZIRqjbkOsVa+FapMc2AsI1Z61z4KSjNZxgFEHyrKYvH5khJLZnMm28pg5CKqGDxbPdpZ0dS+BGoOvPKib2TlwYLrRWeDjch+0yPpj3poPc2NX7zMyFt6W7HXOA8tDhgZBZhTxZSdC0qqWkhBCmCWlDeATdmS9LAmg8565vk9xHXUDFumy7BVPk/g9MJr+l6WmpWr3Dn2J2qzGM54UWOPTmsTWx14rwibw2BlT6J0z1lVB4ukVdy4I2rk74sxohxUbaaowF3XpVK+i0V8lufco03qVeUyOOcWRcSRDsRiXccpJOr3kY9VsYqp6XGoPEpXYmKFZrTS9rUJo3Geu+HYo+nc2NtpKvFPcs64LTrZti7EiVf5Sv318pxq8/k5vNWXYBAdy7c5xhiWf8S9blGR9EDRvZphthe/LAqA7CzG4xY5jlcJix6LPjxyqenUUjU/uez8B5ELK/SPun90yX3g+lIfXdzc/Bnfgyx7F8xSxTqq0u4fo=Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.