16.2 Evaluating Psychotherapies

Advice columnists frequently urge their troubled letter writers to get professional help: “Seek counseling” or “Ask your mate to find a therapist.”

Many Americans share this confidence in psychotherapy’s effectiveness. Before 1950, psychiatrists were the primary providers of mental health care. Today’s providers include clinical and counseling psychologists, clinical social workers, clergy, marital and school counselors, and psychiatric nurses. With such an enormous outlay of time as well as money, effort, and hope, it is important to ask: Are the millions of people worldwide justified in placing their hopes in psychotherapy?

Is Psychotherapy Effective?

16-

The question, though simply put, is not simple to answer. Measuring therapy’s effectiveness is not like taking your body’s temperature after a fever. So how can we assess psychotherapy’s effectiveness? By how we feel about our progress? By how our therapist feels about it? By how our friends and family feel about it? By how our behavior has changed?

Clients’ Perceptions

If clients’ testimonials were the only measuring stick, we could strongly affirm psychotherapy’s effectiveness. When 2900 Consumer Reports readers (1995; Kotkin et al., 1996; Seligman, 1995) related their experiences with mental health professionals, 89 percent said they were at least “fairly well satisfied.” Among those who recalled feeling fair or very poor when beginning therapy, 9 in 10 now were feeling very good, good, or at least so-

We should not dismiss these testimonials. But for several reasons, client testimonials do not persuade psychotherapy’s skeptics:

- People often enter therapy in crisis. When, with the normal ebb and flow of events, the crisis passes, people may attribute their improvement to the therapy. Depressed people often get better no matter what they do.

- Clients believe that treatment will be effective. The placebo effect is the healing power of positive expectations.

- Clients want to believe the therapy was worth the effort. To admit investing time and money in something ineffective is like admitting to having one’s car serviced repeatedly by a mechanic who never fixes it. Self-justification is a powerful human motive, which helps explain why all therapies produce appreciative testimonials.

- Clients generally speak kindly of their therapists. Even if the problems remain, say the critics, clients “work hard to find something positive to say. The therapist had been very understanding, the client had gained a new perspective, he learned to communicate better, his mind was eased, anything at all so as not to have to say treatment was a failure” (Zilbergeld, 1983, p. 117).

As earlier chapters document, we are prone to selective and biased recall and to making judgments that confirm our beliefs. Consider the testimonials gathered in a massive experiment with over 500 Massachusetts boys, aged 5 to 13 years, many of whom seemed bound for delinquency. By the toss of a coin, half the boys were assigned to a 5-

674

Client testimonials were glowing. Some men noted that, had it not been for their counselors, “I would probably be in jail,” “My life would have gone the other way,” or “I think I would have ended up in a life of crime.” Court records offered apparent support: Even among the “difficult” boys in the treatment group, 66 percent had no official juvenile crime record.

But recall psychology’s most powerful tool for sorting reality from wishful thinking: the control group. For every boy in the treatment group, there was a similar boy in a control group, receiving no counseling. Of these untreated men, 70 percent had no juvenile record. On several other measures, such as a record of having committed a second crime, alcohol use disorder, death rate, and job satisfaction, the untreated men exhibited slightly fewer problems. The glowing testimonials of those treated had been unintentionally deceiving.

Clinicians’ Perceptions

Do clinicians’ perceptions give us any more reason to celebrate? Case studies of successful treatment abound. The problem is that clients justify entering psychotherapy by emphasizing their unhappiness and justify leaving by emphasizing their well-

Because people enter therapy when they are extremely unhappy, and usually leave when they are less unhappy, most therapists, like most clients, testify to therapy’s success—

Outcome Research

How, then, can we objectively measure the effectiveness of psychotherapy? How can we determine which people and problems are helped, and by what type of psychotherapy?

In search of answers, psychologists have turned to controlled research studies. Similar research in the 1800s transformed the field of medicine. Physicians, skeptical of many of the fashionable treatments (bleeding, purging, infusions of plant and metal substances), began to realize that many patients got better on their own, without these treatments, and that others died despite them. Sorting fact from superstition required observing patients with and without a particular treatment. Typhoid fever patients, for example, often improved after being bled, convincing most physicians that the treatment worked. Not until a control group was given mere bed rest—

In psychology, the opening challenge to the effectiveness of psychotherapy was issued by British psychologist Hans Eysenck (1952). Launching a spirited debate, he summarized studies showing that two-

meta-analysis a procedure for statistically combining the results of many different research studies.

Why, then, are we still debating psychotherapy’s effectiveness? Because Eysenck also reported similar improvement among untreated persons, such as those who were on waiting lists. With or without psychotherapy, he said, roughly two-

Later research revealed shortcomings in Eysenck’s analyses; his sample was small (only 24 studies of psychotherapy outcomes in 1952). Today, hundreds of studies are available. The best are randomized clinical trials, in which researchers randomly assign people on a waiting list to therapy or to no therapy, and later evaluate everyone, using tests and assessments by others who don’t know whether therapy was given. The results of many such studies are then digested by means of meta-analysis, a statistical procedure that combines the conclusions of a large number of different studies. Simply said, meta-

675

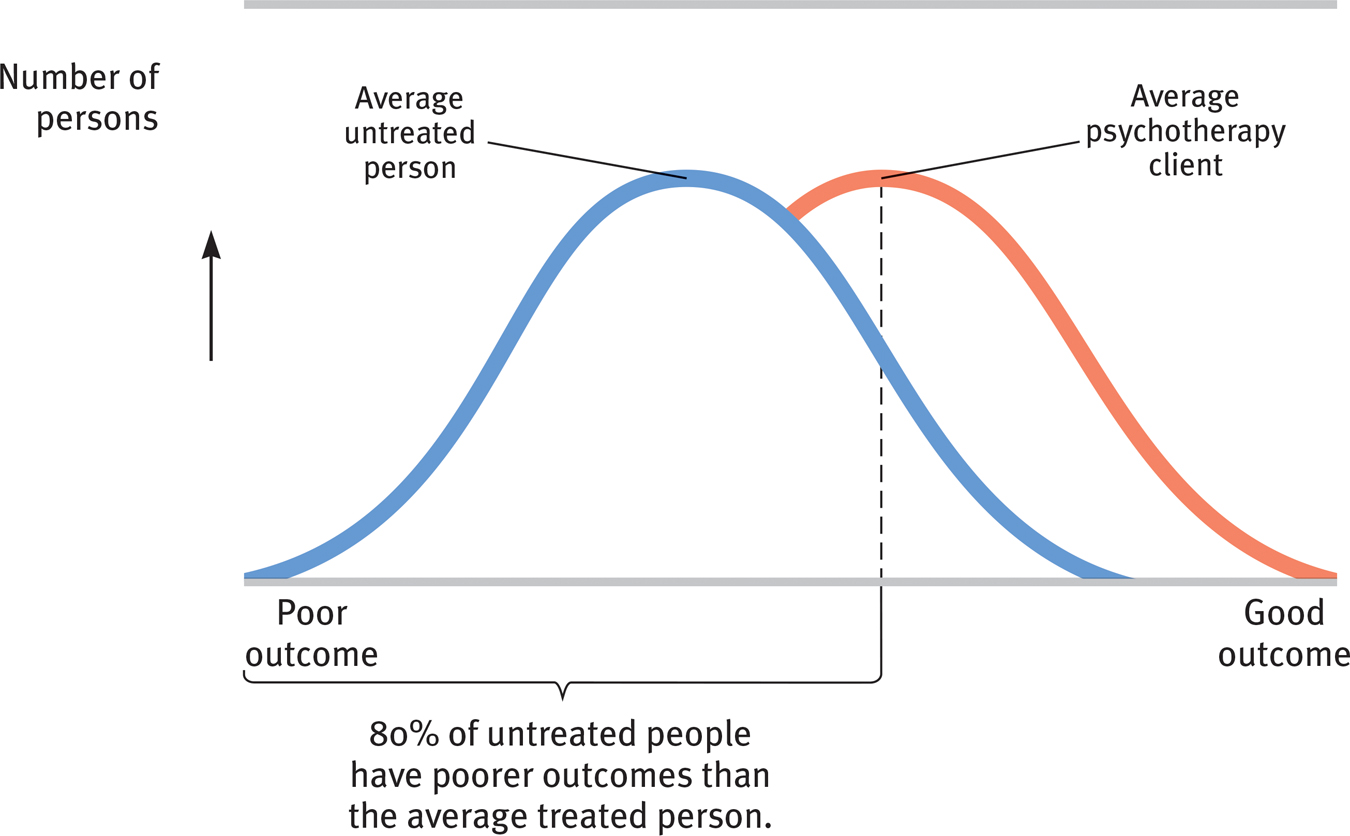

Therapists welcomed the first meta-

Figure 16.3

Figure 16.3Treatment versus no treatment These two normal distribution curves based on data from 475 studies show the improvement of untreated people and psychotherapy clients. The outcome for the average therapy client surpassed the outcome for 80 percent of the untreated people. (Data from Smith et al., 1980.)

Dozens of subsequent summaries have now examined psychotherapy’s effectiveness. Their verdict echoes the results of the earlier outcome studies: Those not undergoing therapy often improve, but those undergoing therapy are more likely to improve, and to improve more quickly and with less risk of relapse. Moreover, between treatment sessions for depression and anxiety, many people experience sudden symptom reductions. Those “sudden gains” bode well for long-

Is psychotherapy also cost-

But note that the claim—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How might the placebo effect bias clients’ and clinicians’ appraisals of the effectiveness of psychotherapies?

The placebo effect is the healing power of belief in a treatment. Patients and therapists who expect a treatment to be effective may believe it was.

Which Psychotherapies Work Best?

16-

So what can we tell people considering psychotherapy, and those paying for it, about which psychotherapy will be most effective for their problem? The statistical summaries and surveys fail to pinpoint any one type of therapy as generally superior (Smith et al., 1977, 1980). Clients seemed equally satisfied, Consumer Reports concluded, whether treated by a psychiatrist, psychologist, or social worker; whether seen in a group or individual context; whether the therapist had extensive or relatively limited training and experience (Seligman, 1995). Other studies concur (Barth et al., 2013). There is little if any connection between clinicians’ experience, training, supervision, and licensing and their clients’ outcomes (Luborsky et al., 2002; Wampold, 2007).

“Whatever differences in treatment efficacy exist, they appear to be extremely small, at best.”

Bruce Wampold et al. (1997)

676

So, was the dodo bird in Alice in Wonderland right: “Everyone has won and all must have prizes”? Not quite. Some forms of therapy get prizes for particular problems, though there is often an overlapping—

Moreover, we can say that therapy is most effective when the problem is clear-

“Different sores have different salves.”

English proverb

But no prizes—

As with some medical treatments, it’s possible for psychological treatments to be not only ineffective but also harmful—

The evaluation question—

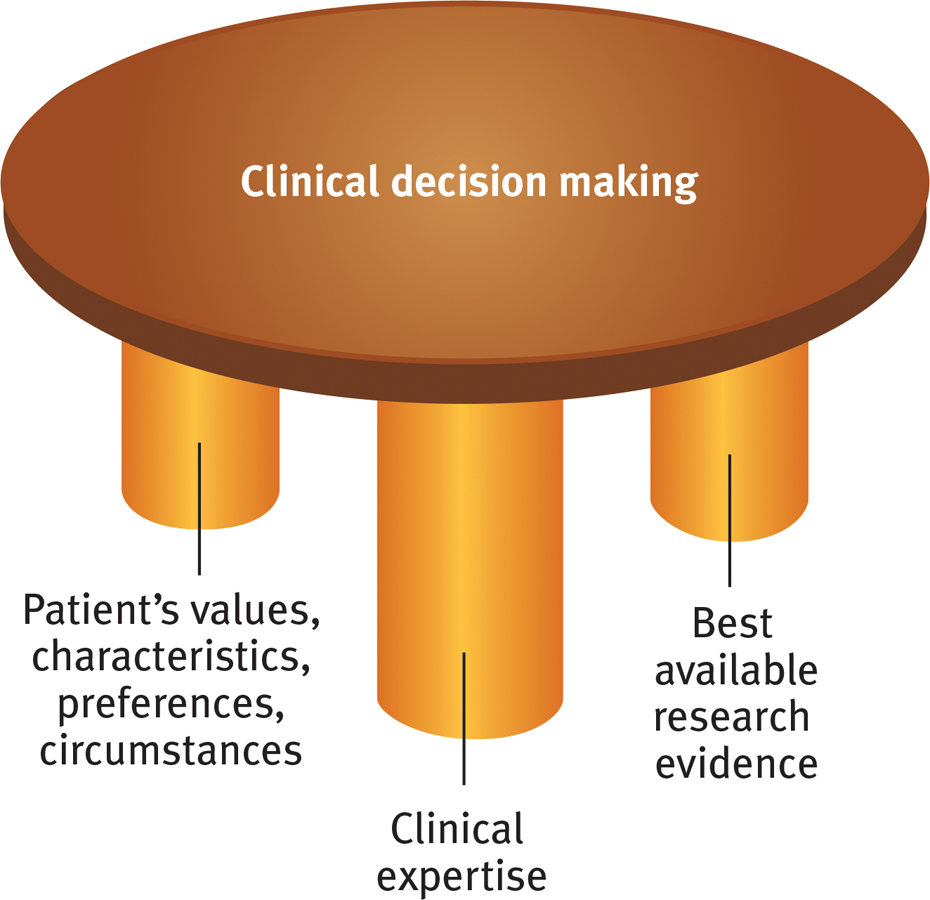

evidence-based practice clinical decision making that integrates the best available research with clinical expertise and patient characteristics and preferences.

On the one side are research psychologists using scientific methods to extend the list of well-

To encourage evidence-based practice in psychology, the American Psychological Association and others (2006; Lilienfeld et al., 2013) urge clinicians to integrate the best available research with clinical expertise and with patient preferences and characteristics. Available therapies “should be rigorously evaluated” and then applied by clinicians who are mindful of their skills and of each patient’s unique situation (FIGURE 16.4). Increasingly, insurer and government support for mental health services requires evidence-

Figure 16.4

Figure 16.4Evidence-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Therapy is most likely to be helpful for those with problems that ______________ (are/are not) well-defined.

are

677

Evaluating Alternative Therapies

16-

The tendency of many abnormal states of mind to return to normal, combined with the placebo effect (the healing power of mere belief in a treatment), creates fertile soil for pseudotherapies. Bolstered by anecdotes, heralded by the media, and broadcast on the Internet, alternative therapies can spread like wildfire. In one national survey, 57 percent of those with a history of anxiety attacks and 54 percent of those with a history of depression had used alternative treatments, such as herbal medicine, massage, and spiritual healing (Kessler et al., 2001).

Testimonials aside, what does the evidence say? This is a tough question, because there is no evidence for or against most of them, though their proponents often feel personal experience is evidence enough. Some, however, have been the subject of controlled research. Let’s consider two of these. As we do, remember that sifting sense from nonsense requires the scientific attitude: being skeptical but not cynical, open to surprises but not gullible.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR)

EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) is a therapy adored by thousands and dismissed by thousands more as a sham—

Does it work? For 84 to 100 percent of single-

“Studies indicate that EMDR is just as effective with fixed eyes. If that conclusion is right, what’s useful in the therapy (chiefly behavioral desensitization) is not new, and what’s new is superfluous.”

Harvard Mental Health Letter, 2002

Why, wonder the skeptics, would rapidly moving one’s eyes while recalling traumas be therapeutic? Some argue that eye movements serve to relax or distract patients, thus allowing the memory-

678

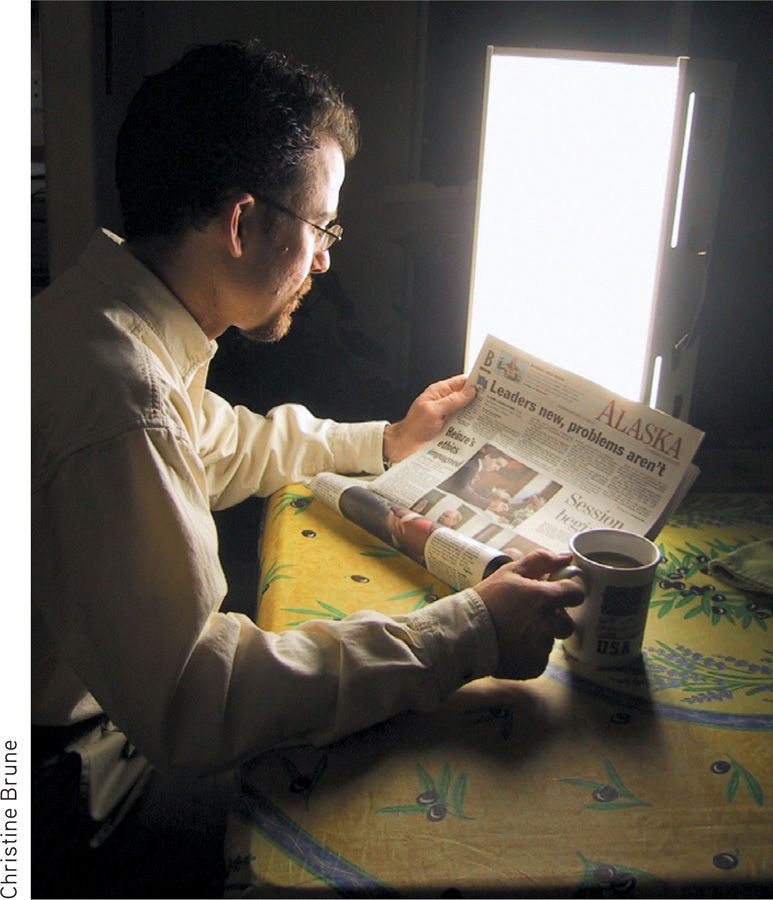

Light Exposure Therapy

Have you ever found yourself oversleeping, gaining weight, and feeling lethargic during the dark mornings and overcast days of winter? There likely was a survival advantage to your distant ancestors’ slowing down and conserving energy during the dark days of winter. For some people, however, especially women and those living far from the equator, the wintertime blahs constitute a seasonal pattern for major depressive disorder. To counteract these dark spirits, National Institute of Mental Health researchers in the early 1980s had an idea: Give people a timed daily dose of intense light. Sure enough, people reported they felt better.

Was light exposure a bright idea, or another dim-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is evidence-based clinical decision making?

Using this approach, therapists make decisions about treatment based on research evidence, clinical expertise, and knowledge of the client.

- Which of the following alternative therapies HAS shown promise as an effective treatment?

|

a. light therapy b. rebirthing therapies |

c. recovered- d. energy therapies |

a

How Do Psychotherapies Help People?

16-

Why have studies found little correlation between therapists’ training and experience and clients’ outcomes? In search of some answers, clinical researchers have studied the common ingredients of various therapies (Frank, 1982; Goldfried & Padawer, 1982; Strupp, 1986; Wampold, 2001, 2007). Their conclusion: They all offer at least three benefits:

679

- Hope for demoralized people People seeking therapy typically feel anxious, depressed, devoid of self-esteem, and incapable of turning things around. What therapy offers is the expectation that, with commitment from the therapy seeker, things can and will get better. This belief, apart from any therapeutic technique, may function as a placebo, improving morale, creating feelings of self-efficacy, and diminishing symptoms (Prioleau et al., 1983).

- A new perspective leading to new behaviors Every therapy also offers people a plausible explanation of their symptoms and an alternative way of looking at themselves or responding to their world. Armed with a believable fresh perspective, they may approach life with a new attitude, open to making changes in their behaviors and their views of themselves.

A caring relationship Effective counselors, such as this chaplain working aboard a ship, form a bond of trust with the people they are serving.

A caring relationship Effective counselors, such as this chaplain working aboard a ship, form a bond of trust with the people they are serving. - An empathic, trusting, caring relationship To say that therapy outcome is unrelated to training and experience is not to say all therapists are equally effective. No matter what therapeutic technique they use, effective therapists are empathic people who seek to understand another’s experience; who communicate their care and concern to the client; and who earn the client’s trust through respectful listening, reassurance, and guidance. Marvin Goldfried and his associates (1998) found such qualities in recorded therapy sessions from 36 recognized master therapists. Some took a cognitive-behavioral approach. Others used psychodynamic principles. Regardless, the striking finding was how similar they were. At key moments, the empathic therapists of both persuasions would help clients evaluate themselves, link one aspect of their life with another, and gain insight into their interactions with others.

therapeutic alliance a bond of trust and mutual understanding between a therapist and client, who work together constructively to overcome the client’s problem.

The emotional bond between therapist and client—

These three common elements are also part of what the growing numbers of self-

***

To recap, people who seek help usually improve. So do many of those who do not undergo psychotherapy, and that is a tribute to our human resourcefulness and our capacity to care for one another. Nevertheless, though the therapist’s orientation and experience appear not to matter much, people who receive some psychotherapy usually improve more than those who do not. People with clear-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Those who undergo psychotherapy are ______________ (more/less) likely to show improvement than those who do not undergo psychotherapy.

more

680

Culture and Values in Psychotherapy

16-

All therapies offer hope, and nearly all therapists attempt to enhance their clients’ sensitivity, openness, personal responsibility, and sense of purpose (Jensen & Bergin, 1988). But therapists also differ from one another and may differ from their clients (Delaney et al., 2007; Kelly, 1990).

These differences can become significant when a therapist from one culture meets a client from another. In North America, Europe, and Australia, for example, most therapists reflect their culture’s individualism, which often gives priority to personal desires and identity, particularly for men. Clients who are immigrants from Asian countries, where people are mindful of others’ expectations, may have trouble relating to therapies that require them to think only of their own well-

Another area of potential values-

Finding a Mental Health Professional

16-

Life for everyone is marked by a mix of serenity and stress, blessing and bereavement, good moods and bad. So, when should we seek a mental health professional’s help? The American Psychological Association offers these common trouble signals:

- Feelings of hopelessness

- Deep and lasting depression

- Self-destructive behavior, such as substance abuse

- Disruptive fears

- Sudden mood shifts

- Thoughts of suicide

- Compulsive rituals, such as hand washing

- Sexual difficulties

- Hearing voices or seeing things that others don’t experience

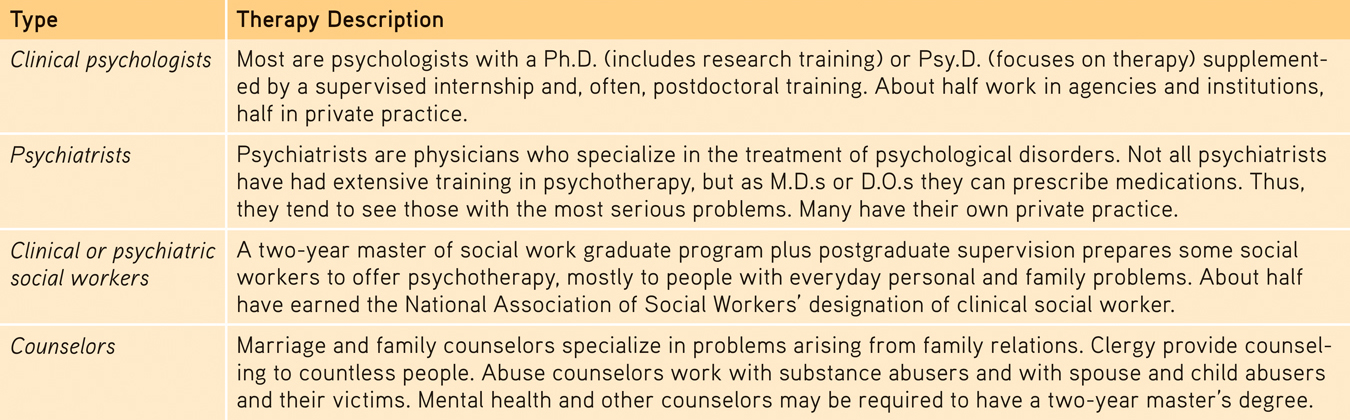

In looking for a therapist, you may want to have a preliminary consultation with two or three. College health centers are generally good starting points, and may offer some free services. You can describe your problem and learn each therapist’s treatment approach. You can ask questions about the therapist’s values, credentials (TABLE 16.3), and fees. And you can assess your own feelings about each of them. The emotional bond between therapist and client is perhaps the most important factor in effective therapy.

Table 16.3

Table 16.3Therapists and Their Training

681

REVIEW: Evaluating Psychotherapies

|

REVIEW | Evaluating Psychotherapies |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

16-

Clients’ and therapists’ positive testimonials cannot prove that psychotherapy is actually effective, and the placebo effect makes it difficult to judge whether improvement occurred because of the treatment.

Using meta-analyses to statistically combine the results of hundreds of randomized psychotherapy outcome studies, researchers have found that those not undergoing treatment often improve, but those undergoing psychotherapy are more likely to improve more quickly, and with less chance of relapse.

16-

No one type of psychotherapy is generally superior to all others. Therapy is most effective for those with clear-cut, specific problems. Some therapies—such as behavior conditioning for treating phobias and compulsions—are more effective for specific disorders. Psychodynamic therapy has been effective for depression and anxiety, and cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies have been effective in coping with anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, and depression. Evidence-based practice integrates the best available research with clinicians’ expertise and patients’ characteristics, preferences, and circumstances.

16-

Abnormal states tend to return to normal on their own, and the placebo effect can create the impression that a treatment has been effective. These two tendencies complicate assessments of alternative therapies (nontraditional therapies that claim to cure certain ailments). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) has shown some effectiveness—not from the eye movement but rather from the exposure therapy nature of the treatments. Light exposure therapy does seem to relieve depression symptoms for those with a seasonal pattern of major depressive disorder by activating a brain region that influences arousal and hormones.

16-

All psychotherapies offer new hope for demoralized people; a fresh perspective; and (if the therapist is effective) an empathic, trusting, and caring relationship. The emotional bond of trust and understanding between therapist and client—the therapeutic alliance—is an important element in effective therapy.

16-

Therapists differ in the values that influence their goals in therapy and their views of progress. These differences may create problems if therapists and clients differ in their cultural or religious perspectives.

16-

A person seeking therapy may want to ask about the therapist’s treatment approach, values, credentials, and fees. An important consideration is whether the therapy seeker feels comfortable and able to establish a bond with the therapist.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

e3qpErNPtK6bxSIDtezg0h8LKhixGl4IAtXiIxMm/HRRJuDCUWA+Y5RX+LI0r/HIhlY5CcRkt72GGpxFpdbbN6QAEnnPAv4sMZj1w3FKaw3mkLuaJH98P0kbJGsK2d4C+56i04tjf6lbpRF34OIFWVB2U1aU6klZxovW9uBwsB/u3dvzIcDNtnztwtp73ytuRY9/NtP8V50h/CY0MI8e1VeLsYT4rBdVlngtwpiUP0LpcW4Q2/6aVi1myigA/KAijwWHSOVpuNvbW/GtqGRxRyjlgNkayyO8jukPTFuCY/CYTA6EpnQ5Fv5+XEPZGNLpmXrs+lqnNCtF/4eMQJQ9uvi7q2cx3Y5P8tkdTQiMOvSW2hp874sPIdNZNxb4BNYGj27EJktAFpfUO7Kg9YE3y7uZCU0iXoh2UVeZYffsA7erSqrygtjgLxmnms7IRcPnF+VIjl39WRBDNTf44AnCd3/ZSsFd9QqlHvxGarRVoTB5QucagPe7fCPhrRyuK4AIx16mBdkzLFGKUS/q8m9qda6BtWl1ZK9OPpyVBo1Jv3zZoy/1l0hfiLtY344R+Oz22UsG/H1/Jjs=Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.