4.2 Evolutionary Psychology: Understanding Human Nature

4-7 How do evolutionary psychologists use natural selection to explain behavior tendencies?

evolutionary psychology the study of the evolution of behavior and the mind, using principles of natural selection.

Behavior geneticists explore the genetic and environmental roots of human differences. Evolutionary psychologists instead focus mostly on what makes us so much alike as humans. They use Charles Darwin’s principle of natural selection—“arguably the most momentous idea ever to occur to a human mind,” said Richard Dawkins (2007)—to understand the roots of behavior and mental processes. The idea, simplified, is this:

natural selection the principle that, among the range of inherited trait variations, those contributing to reproduction and survival will most likely be passed on to succeeding generations.

- Organisms’ varied offspring compete for survival.

- Certain biological and behavioral variations increase organisms’ reproductive and survival chances in their particular environment.

- Offspring that survive are more likely to pass their genes to ensuing generations.

- Thus, over time, population characteristics may change.

To see these principles at work, let’s consider a straightforward example in foxes.

Natural Selection and Adaptation

A fox is a wild and wary animal. If you capture a fox and try to befriend it, be careful. Stick your hand in the cage and, if the timid fox cannot flee, it may snack on your fingers. Russian scientist Dmitry Belyaev wondered how our human ancestors had domesticated dogs from their equally wild wolf forebears. Might he, within a comparatively short stretch of time, accomplish a similar feat by transforming the fearful fox into a friendly fox?

145

To find out, Belyaev set to work with 30 male and 100 female foxes. From their offspring he selected and mated the tamest 5 percent of males and 20 percent of females. (He measured tameness the foxes’ responses to attempts to feed, handle, and stroke them.) Over more than 30 generations of foxes, Belyaev and his successor, Lyud-mila Trut, repeated that simple procedure. Forty years and 45,000 foxes later, they had a new breed of foxes that, in Trut’s (1999) words, were “docile, eager to please, and unmistakably domesticated…. Before our eyes, ‘the Beast’ has turned into ‘beauty,’ as the aggressive behavior of our herd’s wild [ancestors] entirely disappeared.” So friendly and eager for human contact were these animals, so inclined to whimper to attract attention and to lick people like affectionate dogs, that the cash-strapped institute seized on a way to raise funds–marketing its foxes as house pets.

Over time, traits that give an individual or a species a reproductive advantage are selected and will prevail. Animal breeding experiments manipulate genetic selection. Dog breeders have given us sheepdogs that herd, retrievers that retrieve, trackers that track, and pointers that point (Plomin et al., 1997). Psychologists, too, have bred animals to be serene or reactive, quick learners or slow ones.

mutation a random error in gene replication that leads to a change.

Does the same process work with naturally occurring selection? Does natural selection explain our human tendencies? Nature has indeed selected advantageous variations from the new gene combinations produced at each human conception plus the mutations (random errors in gene replication) that sometimes result. But the tight genetic leash that predisposes a dog’s retrieving, a cat’s pouncing, or a bird’s nesting is looser on humans. The genes selected during our ancestral history provide more than a long leash; they give us a great capacity to learn and therefore to adapt to life in varied environments, from the tundra to the jungle. Genes and experience together wire the brain. Our adaptive flexibility in responding to different environments contributes to our fitness—our ability to survive and reproduce.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How are Belyaev and Trut’s breeding practices similar to, and how do they differ from, the way natural selection normally occurs?

Over multiple generations, Belyaev and Trut selected and bred foxes that exhibited a trait they desired: tameness. This process is similar to naturally occurring selection, but it differs in that natural selection normally favors traits (including those arising from mutations) that contribute to reproduction and survival.

- Would the heritability of aggressiveness be greater in Belyaev and Trut’s foxes, or in a wild population of foxes? variation in aggressiveness.

Heritability of aggressiveness would be greater in the wild population, with its greater genetic variation in aggressiveness.

Evolutionary Success Helps Explain Similarities

Human differences grab our attention. The Guinness World Records entertains us with the height of the tallest-ever human, the oldest living person, and the person with the most tattoos. But our deep similarities also demand explanation. In the big picture, our lives are remarkably alike. Visit the international arrivals area at Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, a world hub where arriving passengers meet their excited loved ones. There you will see the same delighted joy in the faces of Indonesian grandmothers, Chinese children, and homecoming Dutch. Evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker (2002, p. 73) has noted that it is no wonder our emotions, drives, and reasoning “have a common logic across cultures”: Our shared human traits “were shaped by natural selection acting over the course of human evolution.”

146

Our Genetic Legacy

Our behavioral and biological similarities arise from our shared human genome, our common genetic profile. No more than 5 percent of the genetic differences among humans arise from population group differences. Some 95 percent of genetic variation exists within populations (Rosenberg et al., 2002). The typical genetic difference between two Icelandic villagers or between two Kenyans is much greater than the average difference between the two groups. Thus, if after a worldwide catastrophe only Icelanders or Kenyans survived, the human species would suffer only “a trivial reduction” in its genetic diversity (Lewontin, 1982).

And how did we develop this shared human genome? At the dawn of human history, our ancestors faced certain questions: Who is my ally, who is my foe? With whom should I mate? What food should I eat? Some individuals answered those questions more successfully than others. For example, women who experienced nausea in the critical first three months of pregnancy were genetically predisposed to avoid certain bitter, strongly flavored, and novel foods. Avoiding such foods has survival value, since they are the very foods most often toxic to prenatal development (Profet, 1992; Schmitt & Pilcher, 2004). Early humans disposed to eat nourishing rather than poisonous foods survived to contribute their genes to later generations. Those who deemed leopards “nice to pet” often did not.

Similarly successful were those whose mating helped them produce and nurture offspring. Over generations, the genes of individuals not so disposed tended to be lost from the human gene pool. As success-enhancing genes continued to be selected, behavioral tendencies and thinking and learning capacities emerged that prepared our Stone Age ancestors to survive, reproduce, and send their genes into the future, and into you.

Despite high infant mortality and rampant disease in past millennia, not one of your countless ancestors died childless.

Across our cultural differences, we even share a “universal moral grammar” (Mikhail, 2007). Men and women, young and old, liberal and conservative, living in Sydney or Seoul, all respond negatively when asked, “If a lethal gas is leaking into a vent and is headed toward a room with seven people, is it okay to push someone into the vent—saving the seven but killing the one?” And they all respond more approvingly when asked if it’s okay to allow someone to fall into the vent, again sacrificing one life but saving seven. Our shared moral instincts survive from a distant past where we lived in small groups in which direct harm-doing was punished. For all such universal human tendencies, from our intense need to give parental care, to our shared fears and lusts, evolutionary theory proposes a one-stop-shopping explanation (Schloss, 2009).

As inheritors of this prehistoric legacy, we are genetically predisposed to behave in ways that promoted our ancestors’ surviving and reproducing. But in some ways, we are biologically prepared for a world that no longer exists. We love the taste of sweets and fats, nutrients that prepared our physically active ancestors to survive food shortages. But few of us now hunt and gather our food. Too often, we search for sweets and fats in fast-food outlets and vending machines. Our natural dispositions, rooted deep in history, are mismatched with today’s junk-food and often inactive lifestyle.

Those who are troubled by an apparent conflict between scientific and religious accounts of human origins may find it helpful to recall from this text’s Prologue that different perspectives of life can be complementary. For example, the scientific account attempts to tell us when and how; religious creation stories usually aim to tell about an ultimate who and why. As Galileo explained to the Grand Duchess Christina, “The Bible teaches how to go to heaven, not how the heavens go.”

Evolutionary Psychology Today

Darwin’s theory of evolution has become one of biology’s organizing principles. “Virtually no contemporary scientists believe that Darwin was basically wrong,” noted Jared Diamond (2001). Today, Darwin’s theory lives on in the second Darwinian revolution, the application of evolutionary principles to psychology. In concluding On the Origin of Species, Darwin (1859, p. 346) anticipated this, foreseeing “open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation.”

147

Elsewhere in this text, we address questions that intrigue evolutionary psychologists: Why do infants start to fear strangers about the time they become mobile? Why are biological fathers so much less likely than unrelated boyfriends to abuse and murder the children with whom they share a home? Why do so many more people have phobias about spiders, snakes, and heights than about more dangerous threats, such as guns and electricity? And why do we fear air travel so much more than driving?

To see how evolutionary psychologists think and reason, let’s pause to explore their answers to two questions: How are males and females alike? How and why does their sexuality differ?

An Evolutionary Explanation of Human Sexuality

4-8 How might an evolutionary psychologist explain male-female differences in sexuality and mating preferences?

Having faced many similar challenges throughout history, males and females have adapted in similar ways: We eat the same foods, avoid the same predators, and perceive, learn, and remember similarly. It is only in those domains where we have faced differing adaptive challenges—most obviously in behaviors related to reproduction—that we differ, say evolutionary psychologists.

Male-Female Differences in Sexuality

And differ we do. Consider sex drives. Both men and women are sexually motivated, some women more so than many men. Yet, on average, who thinks more about sex? Masturbates more often? Initiates more sex? Views more pornography? The answers worldwide: men, men, men, and men (Baumeister et al., 2001; Lippa, 2009; Petersen & Hyde, 2010). No surprise, then, that in one BBC survey of more than 200,000 people in 53 nations, men everywhere more strongly agreed that “I have a strong sex drive” and “It doesn’t take much to get me sexually excited” (Lippa, 2008).

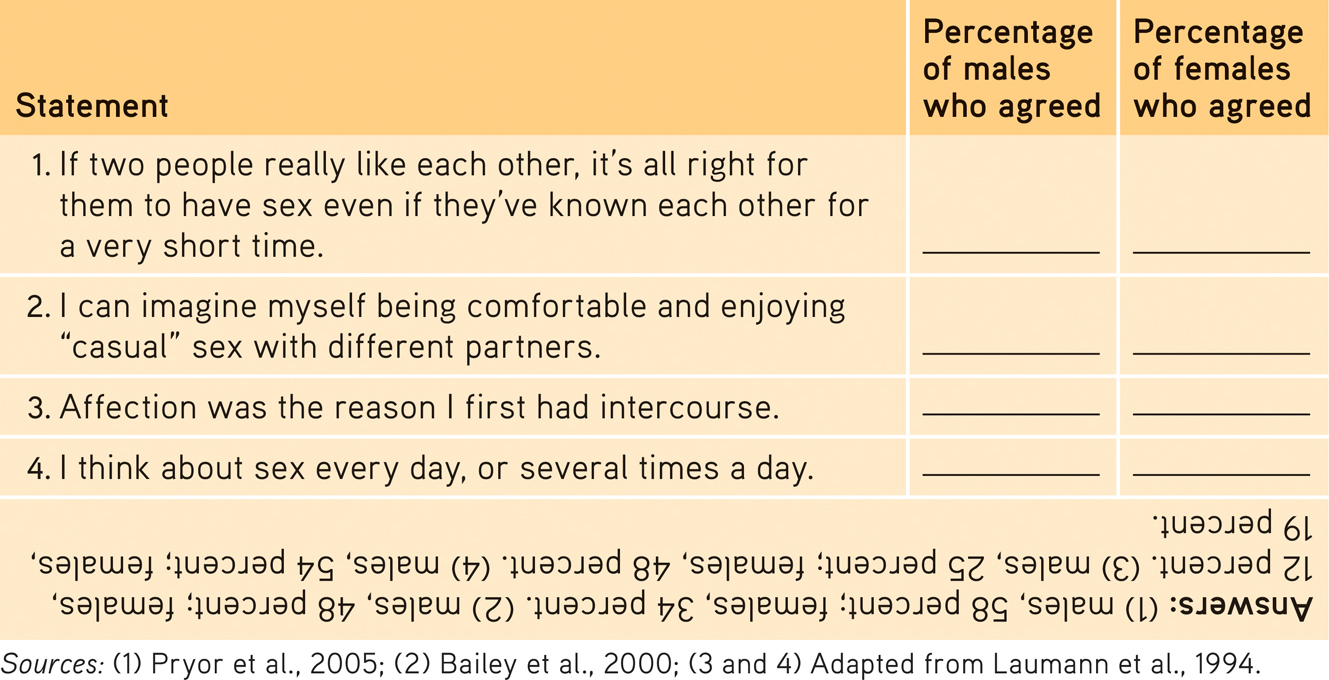

Indeed, “with few exceptions anywhere in the world,” reported cross-cultural psychologist Marshall Segall and his colleagues (1990, p. 244), “males are more likely than females to initiate sexual activity.” This is the largest sexuality difference between males and females, but there are others (Hyde, 2005; Petersen & Hyde, 2010; Regan & Atkins, 2007). To see if you can predict some of these differences, take the quiz in TABLE 4.1 below.

Table 4.1

Table 4.1Predict the Responses

Researchers asked samples of U.S. adults whether they agreed or disagreed with the following statements. For each item below, give your best guess about the percentage who agreed with the statement.

Compared with lesbians, gay men (like straight men) have reported more interest in uncommitted sex, more responsiveness to visual sexual stimuli, and more concern with their partner’s physical attractiveness (Bailey et al., 1994; Doyle, 2005; Schmitt, 2007; Sprecher et al., 2013). Gay male couples report having sex more often than do lesbian couples (Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007). And in the first year of Vermont’s same-sex civil unions, and among the first 12,000 Massachusetts same-sex marriages, a striking fact emerged. Although men are roughly two-thirds of the gay population, they were only about one-third of those electing legal partnership (Crary, 2009; Rothblum, 2007).

“It’s not that gay men are oversexed; they are simply men whose male desires bounce off other male desires rather than off female desires.”

Steven Pinker, How the Mind Works, 1997

Webster, G. D., Jonason, P. K., & Schember, T. O. (2009). Hot topics and popular papers in evolutionary psychology: Analyses of title words and citation counts in Evolution and Human Behavior, 1979–2008. Evolutionary Psychology, 7, 348–362.

148

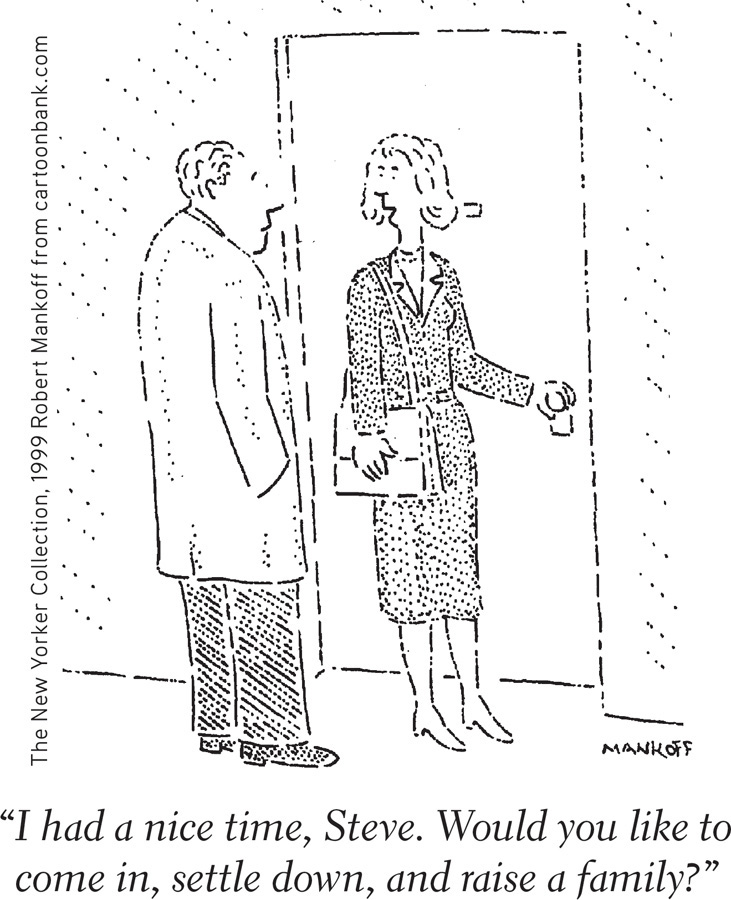

Heterosexual men often misperceive a woman’s friendliness as a sexual come-on (Abbey, 1987). In one speed-dating study, men believed their dating partners expressed more sexual interest than the partners reported actually expressing (Perilloux et al., 2012). This sexual overperception bias is strongest among men who require little emotional closeness before intercourse (Howell et al., 2012; Perilloux et al., 2012).

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

To listen to experts discuss evolutionary psychology and sex differences, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Evolutionary Psychology and Sex Differences.

Natural Selection and Mating Preferences

The principle of natural selection proposes that nature selects traits and appetites that contribute to survival and reproduction. Evolutionary psychologists use this principle to explain how men and women differ more in the bedroom than in the boardroom. Our natural yearnings, they say, are our genes’ way of reproducing themselves. “Humans are living fossils—collections of mechanisms produced by prior selection pressures” (Buss, 1995).

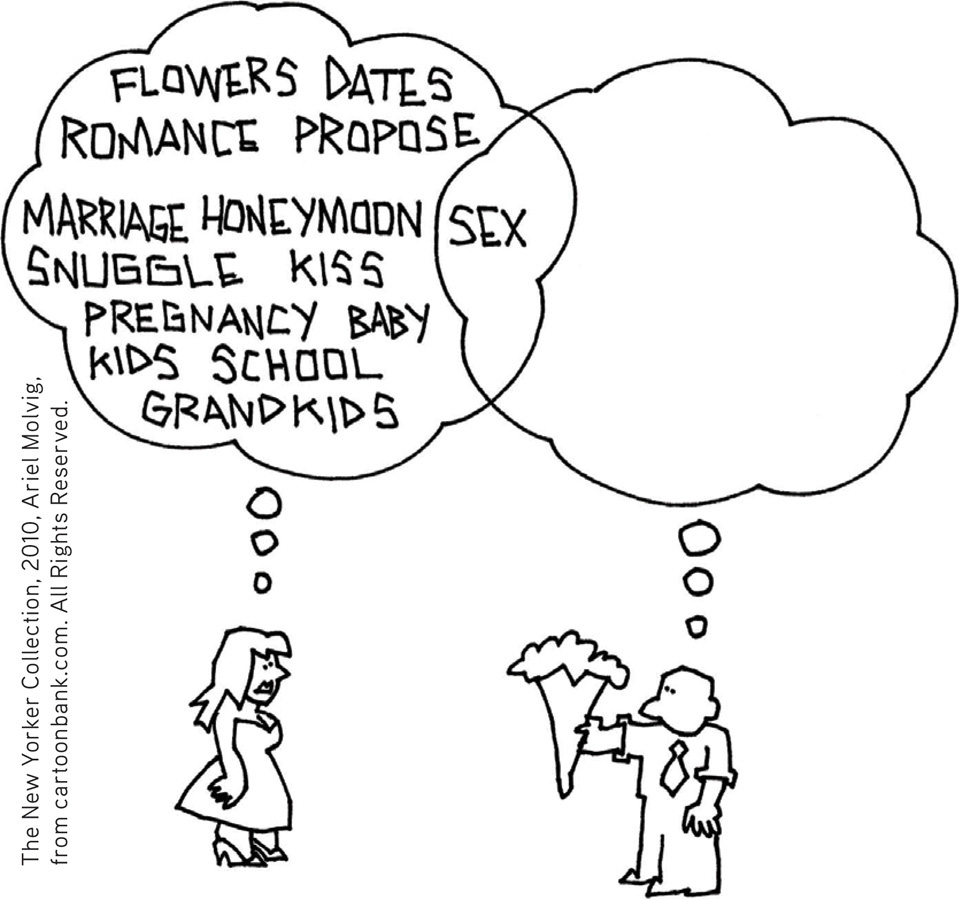

Why do women tend to be choosier than men when selecting sexual partners? Women have more at stake. To send her genes into the future, a woman must—at a minimum—conceive and protect a fetus growing inside her body for up to nine months. And unlike men, women are limited in how many children they can have between puberty and menopause. No surprise then, that heterosexual women prefer partners who will offer their joint offspring support and protection. They prefer stick-around dads over likely cads. Heterosexual women are attracted to tall men with slim waists and broad shoulders—all signs of reproductive success (Mautz et al., 2012). And they prefer men who appear mature, dominant, bold, and affluent (Asendorpf et al., 2011; Gangestad & Simpson, 2000; Singh, 1995). One study of hundreds of Welsh pedestrians asked people to rate a driver pictured at the wheel of a humble Ford Fiesta or a swanky Bentley. Men said a female driver was equally attractive in both cars. Women, however, found a male driver more attractive if he was in the luxury car (Dunn & Searle, 2010). When put in a mating mindset, men buy more showy items, express more aggressive intentions, and take more risks (Baker & Maner, 2009; Griskevicius et al., 2009; Shan et al., 2012; Sundie et al., 2011).

149

The data are in, say evolutionists: Men pair widely; women pair wisely. And what traits do straight men find desirable? Some, such as a woman’s smooth skin and youthful shape, cross place and time, and they convey health and fertility (Buss, 1994). Mating with such women might give a man a better chance of sending his genes into the future. And sure enough, men feel most attracted to women whose waists (thanks to their genes or their surgeons) are roughly a third narrower than their hips—a sign of future fertility (Perilloux et al., 2010). Even blind men show this preference for women with a low waist-to-hip ratio (Karremans et al., 2010). Men are most attracted to women whose ages in the ancestral past (when ovulation began later than today) would be associated with peak fertility (Kenrick et al., 2009). Thus, teen boys are most excited by a woman several years older than themselves, mid-twenties men prefer women around their own age, and older men prefer younger women. This pattern consistently appears across European singles ads, Indian marital ads, and marriage records from North and South America, Africa, and the Philippines (Singh, 1993; Singh & Randall, 2007).

“She’s beautiful, and therefore to be woo’d.”

William Shakespeare, King Henry IV

There is a principle at work here, say evolutionary psychologists: Nature selects behaviors that increase the likelihood of sending one’s genes into the future. As mobile gene machines, we are designed to prefer whatever worked for our ancestors in their environments. They were genetically predisposed to act in ways that would leave grandchildren. Had they not been, we wouldn’t be here. As carriers of their genetic legacy, we are similarly predisposed.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

To experience a demonstration and explanation of evolutionary psychology and mating preferences, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Dating and Mating.

Critiquing the Evolutionary Perspective

4-9 What are the key criticisms of evolutionary explanations of human sexuality, and how do evolutionary psychologists respond?

Most psychologists agree that natural selection prepares us for survival and reproduction. But critics say there is a weakness in the reasoning evolutionary psychologists use to explain our mating preferences. Let’s consider how an evolutionary psychologist might explain the findings in a startling study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989), and how a critic might object.

Participants were approached by a “stranger” of the other sex (someone working for the experimenter). The stranger remarked “I have been noticing you around campus. I find you to be very attractive,” and then asked one of three questions:

- Would you go out with me tonight?

- Would you come over to my apartment tonight?

- Would you go to bed with me tonight?

150

What percentage of men and women do you think agreed to each offer? The evolutionary explanation of sexuality predicts that women will be choosier than men in selecting their sexual partners and will be less willing to hop in bed with a complete stranger. In fact, not a single woman—but 70 percent of men—agreed to question 3. A recent repeat of this study produced a similar result in France (Gueguen, 2011). The research seemed to support an evolutionary explanation.

Or did it? Critics note that evolutionary psychologists start with an effect—in this case, the survey result showing that men were more likely to accept casual sex offers—and work backward to explain what happened. What if research showed the opposite effect? If men refused an offer for casual sex, might we not reason that men who partner with one woman for life make better fathers, whose children more often survive?

social script culturally modeled guide for how to act in various situations.

Other critics ask why we should try to explain today’s behavior based on decisions our distant ancestors made thousands of years ago. They believe social learning theory offers a better, more immediate explanation for these results. Perhaps women learn social scripts—their culture’s guide to how people should act in certain situations. By watching and imitating others in their culture, they may learn that sexual encounters with strangers are dangerous, and that men who ask for casual sex will not offer women much sexual pleasure (Conley, 2011). This alternative explanation of the study’s effects proposes that women react to sexual encounters in ways that their modern culture teaches them.

A third criticism focuses on the social consequences of accepting an evolutionary explanation. Are heterosexual men truly hard-wired to have sex with any woman who approaches them? If so, does it mean that men have no moral responsibility to remain faithful to their partners? Does this explanation excuse men’s sexual aggression—“boys will be boys”—because of our evolutionary history?

Evolutionary psychologists agree that much of who we are is not hard-wired. “Evolution forcefully rejects a genetic determinism,” insisted one research team (Confer et al., 2010). And evolutionary psychologists remind us that men and women, having faced similar adaptive problems, are far more alike than different. Natural selection has prepared us to be flexible. We humans have a great capacity for learning and social progress. We adjust and respond to varied environments. We adapt and survive, whether we live in the Arctic or the desert.

“It is dangerous to show a man too clearly how much he resembles the beast, without at the same time showing him his greatness. It is also dangerous to allow him too clear a vision of his greatness without his baseness. It is even more dangerous to leave him in ignorance of both.”

Blaise Pascal, Pensées, 1659

Evolutionary psychologists also agree with their critics that some traits and behaviors, such as suicide, are hard to explain in terms of natural selection (Barash, 2012; Confer et al., 2010). But they ask us to remember evolutionary psychology’s scientific goal: to explain behaviors and mental traits by offering testable predictions using principles of natural selection. We can, for example, scientifically test hypotheses such as: Do we tend to favor others to the extent that they share our genes or can later return our favors? (The answer is Yes.) They also remind us that studying how we came to be need not dictate how we ought to be. Understanding our tendencies can help us overcome them.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do evolutionary psychologists explain sex differences in sexuality?

Evolutionary psychologists theorize that females have inherited their ancestors’ tendencies to be more cautious, sexually, because of the challenges associated with incubating and nurturing offspring. Males have inherited an inclination to be more casual about sex, because their act of fathering requires a smaller investment.

- What are the three main criticisms of the evolutionary explanation of human sexuality?

(1) It starts with an effect and works backward to propose an explanation. (2) Unethical and immoral men could use such explanations to rationalize their behavior toward women. (3) This explanation may overlook the effects of cultural expectations and socialization.

151

REVIEW: Evolutionary Psychology: Understanding Human Nature

|

REVIEW | Evolutionary Psychology: Understanding Human Nature |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

4-7 How do evolutionary psychologists use natural selection to explain behavior tendencies?

Evolutionary psychologists seek to understand how our traits and behavior tendencies are shaped by natural selection, as genetic variations increasing the odds of reproducing and surviving in their particular environment are most likely to be passed on to future generations. Some variations arise from mutations (random errors in gene replication), others from new gene combinations at conception. Humans share a genetic legacy and are predisposed to behave in ways that promoted our ancestors’ surviving and reproducing. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution is an organizing principle in biology. He anticipated today’s application of evolutionary principles in psychology.

4-8 How might an evolutionary psychologist explain male-female differences in sexuality and mating preferences?

Men tend to have a recreational view of sexual activity; women tend to have a relational view. Evolutionary psychologists reason that men’s attraction to multiple healthy, fertile-appearing partners increases their chances of spreading their genes widely. Because women incubate and nurse babies, they increase their own and their children’s chances of survival by searching for mates with the potential for long-term investment in their joint offspring.

4-9 What are the key criticisms of evolutionary explanations of human sexuality, and how do evolutionary psychologists respond?

Critics argue that evolutionary psychologists start with an effect and work backward to an explanation. They also charge that evolutionary psychologists try to explain today’s behavior based on decisions our distant ancestors made thousands of years ago, noting that a better, more immediate explanation takes learned social scripts into account. And, the critics wonder, does this kind of explanation absolve people from taking responsibility for their sexual behavior? Evolutionary psychologists respond that understanding our predispositions can help us overcome them. They recognize the importance of social and cultural influences, but they also cite the value of testable predictions based on evolutionary principles.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

axOJH4loIcHWJqkASRa5eT+BgDZpU0rWhwiGicDpilBTTK5EZmYq/PECKuEvATOvHDAnjs+Ni+5SxsHcljVFQ97cx2A33cRpMDt+Vydun4sorZyx4YVtf0/eF4KJnJbPKEMpEvX1uaaETQYSJ6V2D917O6IalClAhvfKcBC6KA7Hqxq0csXRFQ2aNv1YbvsttiXN4vQLaAMd2N4v/qEME0cMx7qAmwm62wFmOMcAERM4R19/69x4rRSxzaJz2AwinX73gjSZYGOJoc71CqrDoyh+EMyJVEuulbFfM+FoLBg9YKKn5qZf7ANDbYFwhS72gI+aftNadmX7pcKehWEnWGTa+C/uC8s5YG++kuhGbWO9eFXbsWRsSA9/UWjsOpL+ga8w8Fu+PHYao72nja+NQfJ6GfB9gvFS/UETCXIhyXwcxsPH1U+CWoSb3531fGUIv195aO/5XTAHy/REXrnAkRgYad5cMtMxvbRIxyCt3jK5ELdED3nkbr7MhdQhRUqwsuTJjEP8ga3hNhSDpjN7Bjs/D+JqT/+Wt5ZgwgQIOObVqyG0hlowP3ZVVzQuDg5KqPn5CUc1mgi+0/H4aLyMy3Zl14Yxhw8ITo9tmwwmCrRySTvpUse  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.