4.3 Culture, Gender, and Other Environmental Influences

interaction the interplay that occurs when the effect of one factor (such as environment) depends on another factor (such as heredity).

From conception onward, we are the product of a cascade of interactions between our genetic predispositions and our surrounding environments (McGue, 2010). Our genes affect how people react to and influence us. Forget nature versus nurture; think nature via nurture.

Imagine two babies, one genetically predisposed to be attractive, sociable, and easygoing, the other less so. Assume further that the first baby attracts more affectionate and stimulating care and so develops into a warmer and more outgoing person. As the two children grow older, the more naturally outgoing child may seek more activities and friends that encourage further social confidence.

What has caused their resulting personality differences? Neither heredity nor experience acts alone. Environments trigger gene activity. And our genetically influenced traits evoke significant responses in others. Thus, a child’s impulsivity and aggression may evoke an angry response from a parent or teacher, who reacts warmly to model children in the family or classroom. In such cases, the child’s nature and the parents’ nurture interact. Gene and scene dance together.

152

Identical twins not only share the same genetic predispositions, they also seek and create similar experiences that express their shared genes (Kandler et al., 2012). Evocative interactions may help explain why identical twins raised in different families recall their parents’ warmth as remarkably similar—almost as similar as if they had been raised by the same parents (Plomin et al., 1988, 1991, 1994). Fraternal twins have more differing recollections of their early family life—even if raised in the same family! “Children experience us as different parents, depending on their own qualities,” noted Sandra Scarr (1990). Moreover, a selection effect may be at work. As we grow older, we select environments well suited to our natures. Talkative children may become sales-people. Shy children may become laboratory technicians.

How Does Experience Influence Development?

Our genes, when expressed in specific environments, influence our developmental differences. We are not “blank slates” (Kenrick et al., 2009). We are more like coloring books, with certain lines predisposed and experience filling in the full picture. We are formed by nature and nurture. But what are the most influential components of our nurture? How do our early experiences, our family and peer relationships, and all our other experiences guide our development and contribute to our diversity?

The formative nurture that conspires with nature begins at conception, with the prenatal environment in the womb, where embryos receive differing nutrition and varying levels of exposure to toxic agents. Nurture then continues outside the womb, where our early experiences foster brain development.

Experience and Brain Development

4-10 How do early experiences modify the brain?

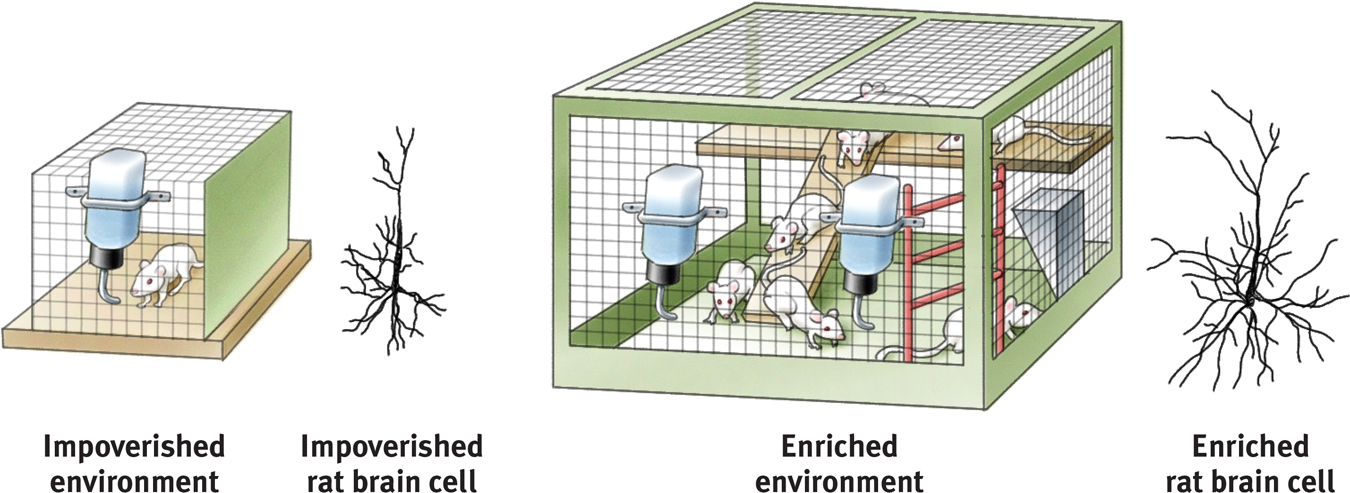

Our genes dictate our overall brain architecture, but experience fills in the details. Developing neural connections prepare our brain for thought, language, and other later experiences. So how do early experiences leave their “fingerprints” in the brain? Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) opened a window on that process when they raised some young rats in solitary confinement and others in a communal playground. When they later analyzed the rats’ brains, those who died with the most toys had won. The rats living in the enriched environment, which simulated a natural environment, usually developed a heavier and thicker brain cortex (FIGURE 4.4).

Figure 4.4

Figure 4.4Experience affects brain development Mark Rosenzweig, David Krech, and their colleagues (1962) raised rats either alone in an environment without playthings, or with other rats in an environment enriched with playthings changed daily. In 14 of 16 repetitions of this basic experiment, rats in the enriched environment developed significantly more cerebral cortex (relative to the rest of the brain’s tissue) than did those in the impoverished environment.

Rosenzweig was so surprised by this discovery that he repeated the experiment several times before publishing his findings (Renner & Rosenzweig, 1987; Rosenzweig, 1984). So great are the effects that, shown brief video clips of rats, you could tell from their activity and curiosity whether their environment had been impoverished or enriched (Renner & Renner, 1993). After 60 days in the enriched environment, the rats’ brain weights increased 7 to 10 percent and the number of synapses mushroomed by about 20 percent (Kolb & Whishaw, 1998).

153

Such results have motivated improvements in environments for laboratory, farm, and zoo animals—and for children in institutions. Stimulation by touch or massage also benefits infant rats and premature babies (Field et al., 2007). “Handled” infants of both species develop faster neurologically and gain weight more rapidly. Preemies who have had skin-to-skin contact with their mothers sleep better, experience less stress, and show better cognitive development 10 years later (Feldman et al., 2014).

Nature and nurture interact to sculpt our synapses. Brain maturation provides us with an abundance of neural connections. Experiences trigger sights and smells, touches and tugs, and activate and strengthen connections. Unused neural pathways weaken. Like forest pathways, popular tracks are broadened and less-traveled ones gradually disappear. By puberty, this pruning process results in a massive loss of unemployed connections.

Here at the juncture of nurture and nature is the biological reality of early childhood learning. During early childhood—while excess connections are still on call—youngsters can most easily master such skills as the grammar and accent of another language. Lacking any exposure to language before adolescence, a person will never master any language. Likewise, lacking visual experience during the early years, a person whose vision is later restored by cataract removal will never achieve normal perceptions (Gregory, 1978; Wiesel, 1982). Without that early visual stimulation, the brain cells normally assigned to vision will die or be diverted to other uses. The maturing brain’s rule: Use it or lose it.

“Genes and experiences are just two ways of doing the same thing—wiring synapses.”

Joseph LeDoux, The Synaptic Self, 2002

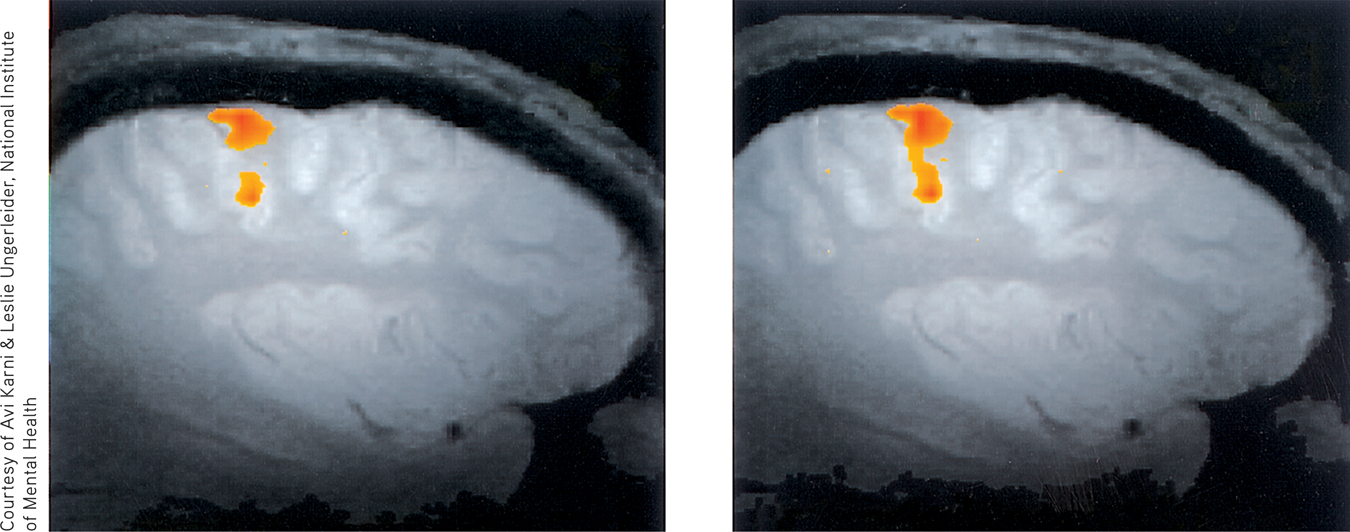

Although normal stimulation during the early years is critical, the brain’s development does not end with childhood. Thanks to the brain’s amazing plasticity, our neural tissue is ever changing and reorganizing in response to new experiences. New neurons are also born. If a monkey pushes a lever with the same finger many times a day, brain tissue controlling that finger will change to reflect the experience (FIGURE 4.5). Human brains work similarly. Whether learning to keyboard, skateboard, or navigate London’s streets, we perform with increasing skill as our brain incorporates the learning (Ambrose, 2010; Maguire et al., 2000).

Figure 4.5

Figure 4.5A trained brain A well-learned finger-tapping task activates more motor cortex neurons (orange area, right) than were active in this monkey’s brain before training (left). (From Karni et al., 1998.)

How Much Credit or Blame Do Parents Deserve?

4-11 In what ways do parents and peers shape children’s development?

In procreation, a woman and a man shuffle their gene decks and deal a life-forming hand to their child-to-be, who is then subjected to countless influences beyond their control. Parents, nonetheless, feel enormous satisfaction in their children’s successes or guilt and shame over their failures. They beam over the child who wins trophies and titles. They wonder where they went wrong with the child who is repeatedly in trouble. Freudian psychiatry and psychology encouraged such ideas by blaming problems from asthma to schizophrenia on “bad mothering.” Society has reinforced such parent blaming: Believing that parents shape their offspring as a potter molds clay, people readily praise parents for their children’s virtues and blame them for their children’s vices. Popular culture endlessly proclaims the psychological harm toxic parents inflict on their fragile children. No wonder having and raising children can seem so risky.

154

But do parents really produce future adults with an inner wounded child by being (take your pick from the toxic-parenting lists) overbearing—or uninvolved? Pushy—or indecisive? Overprotective—or distant? Are children really so easily wounded? If so, should we then blame our parents for our failings, and ourselves for our children’s failings? Or does talk of wounding fragile children through normal parental mistakes trivialize the brutality of real abuse?

Parents do matter. But parenting wields its largest effects at the extremes: the abused children who become abusive, the neglected who become neglectful, the loved but firmly handled who become self-confident and socially competent. The power of the family environment also appears in the remarkable academic and vocational successes of children of people who fled war-torn Vietnam and Cambodia—successes attributed to close-knit, supportive, even demanding families (Caplan et al., 1992). Asian Americans and European Americans differ in their expectations for mothering. An Asian-American mother may push (or “nag,” as one study called it) her children to do well, but that pressure likely won’t strain their relationship (Fu & Markus, 2014). Having a supportive “Tiger Mother”—one who pushes them to do well and works alongside them (versus forcing them to work alone)—motivates Asian-American children to work harder. European Americans might view that kind of parenting as “smothering-mothering,” believing that it undermines children’s motivation (Deal, 2011).

Yet in personality measures, shared environmental influences from the womb onward typically account for less than 10 percent of children’s differences. In the words of behavior geneticists Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels (1987; Plomin, 2011), “Two children in the same family are [apart from their shared genes] as different from one another as are pairs of children selected randomly from the population.” To developmental psychologist Sandra Scarr (1993), this implied that “parents should be given less credit for kids who turn out great and blamed less for kids who don’t.” Knowing children are not easily sculpted by parental nurture, perhaps parents can relax a bit more and love their children for who they are.

Peer Influence

As children mature, what other experiences do the work of nurturing? At all ages, but especially during childhood and adolescence, we seek to fit in with our groups (Harris, 1998, 2000):

- Preschoolers who disdain a certain food often will eat that food if put at a table with a group of children who like it.

- Children who hear English spoken with one accent at home and another in the neighborhood and at school will invariably adopt the accent of their peers, not their parents. Accents (and slang) reflect culture, “and children get their culture from their peers,” as Judith Rich Harris (2007), has noted.

- Teens who start smoking typically have friends who model smoking, suggest its pleasures, and offer cigarettes (J. S. Rose et al., 1999; R. J. Rose et al., 2003). Part of this peer similarity may result from a selection effect, as kids seek out peers with similar attitudes and interests. Those who smoke (or don’t) may select as friends those who also smoke (or don’t).

“Men resemble the times more than they resemble their fathers.”

Ancient Arab proverb

- Put two teens together and their brains become hypersensitive to reward (Albert et al., 2013). This increased activation helps explain why teens take more driving risks when with friends than they do when alone (Chein et al., 2011).

155

Howard Gardner (1998) has concluded that parents and peers are complementary:

Parents are more important when it comes to education, discipline, responsibility, orderliness, charitableness, and ways of interacting with authority figures. Peers are more important for learning cooperation, for finding the road to popularity, for inventing styles of interaction among people of the same age. Youngsters may find their peers more interesting, but they will look to their parents when contemplating their own futures. Moreover, parents [often] choose the neighborhoods and schools that supply the peers.

This power to select a child’s neighborhood and schools gives parents an ability to influence the culture that shapes the child’s peer group. And because neighborhood influences matter, parents may want to become involved in intervention programs that aim at a whole school or neighborhood. If the vapors of a toxic climate are seeping into a child’s life, that climate—not just the child—needs reforming. Even so, peers are but one medium of cultural influence. As an African proverb declares, “It takes a village to raise a child.”

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

What is the selection effect, and how might it affect a teen’s decision to drink alcohol?

Adolescents tend to select out similar others and sort themselves into like-minded groups. This could lead a teen who wants to experiment with drinking alcohol to seek out others who already drink alcohol.

Cultural Influences

4-12 How does culture affect our behavior?

Compared with the narrow path taken by flies, fish, and foxes, the road along which environment drives us is wider. The mark of our species—nature’s great gift to us—is our ability to learn and adapt. We come equipped with a huge cerebral hard drive ready to receive cultural software.

culture the enduring behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next.

Culture is the behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group of people and transmitted from one generation to the next (Brislin, 1988; Cohen, 2009). Human nature, noted Roy Baumeister (2005), seems designed for culture. We are social animals, but more. Wolves are social animals; they live and hunt in packs. Ants are incessantly social, never alone. But “culture is a better way of being social,” noted Baumeister. Wolves function pretty much as they did 10,000 years ago. You and I enjoy things unknown to most of our century-ago ancestors, including electricity, indoor plumbing, antibiotics, and the Internet. Culture works.

Other animals exhibit smaller kernels of culture. Primates have local customs of tool use, grooming, and courtship. Chimpanzees sometimes invent customs using leaves to clean their bodies, slapping branches to get attention, and doing a “rain dance” by slowly displaying themselves at the start of rain and pass them on to their peers and offspring (Whiten et al., 1999). Culture supports a species’ survival and reproduction by transmitting learned behaviors that give a group an edge. But human culture does more.

Thanks to our mastery of language, we humans enjoy the preservation of innovation. Within the span of this day, we have used Google, laser printers, digital hearing technology [DM], and a GPS running watch [ND]. On a grander scale, we have culture’s accumulated knowledge to thank for the last century’s 30-year extension of the average human life expectancy in most countries where this book is being read. Moreover, culture enables an efficient division of labor. Although two lucky people get their name on this book’s cover, the product actually results from the coordination and commitment of a gifted team of people, no one of whom could produce it alone.

156

Across cultures, we differ in our language, our monetary systems, our sports, even which side of the road we drive on. But beneath these differences is our great similarity—our capacity for culture. Culture transmits the customs and beliefs that enable us to communicate, to exchange money for things, to play, to eat, and to drive with agreed-upon rules and without crashing into one another.

Variation Across Cultures

We see our adaptability in cultural variations among our beliefs and our values, in how we nurture our children and bury our dead, and in what we wear (or whether we wear anything at all). We are ever mindful that the readers of this book are culturally diverse. You and your ancestors reach from Australia to Africa and from Singapore to Sweden.

Riding along with a unified culture is like running with the wind: As it carries us along, we hardly notice it is there. When we try running against the wind we feel its force. Face to face with a different culture, we become aware of the cultural winds. Visiting Europe, most North Americans notice the smaller cars, the left-handed use of the fork, the uninhibited attire on the beaches. Stationed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait, American and European soldiers alike realized how liberal their home cultures were. Arriving in North America, visitors from Japan and India struggle to understand why so many people wear their dirty street shoes in the house.

norm an understood rule for accepted and expected behavior. Norms prescribe “proper” behavior.

But humans in varied cultures nevertheless share some basic moral ideas. Even before they can walk, babies prefer helpful people over naughty ones (Hamlin et al., 2011). Yet each cultural group also evolves its own norms—rules for accepted and expected behavior. The British have a norm for orderly waiting in line. Many South Asians use only the right hand’s fingers for eating. Sometimes social expectations seem oppressive: “Why should it matter how I dress?” Yet, norms grease the social machinery and free us from self-preoccupation.

When cultures collide, their differing norms often befuddle. Should we greet people by shaking hands, bowing, or kissing each cheek? Knowing what sorts of gestures and compliments are culturally appropriate, we can relax and enjoy one another without fear of embarrassment or insult.

When we don’t understand what’s expected or accepted, we may experience culture shock. People from Mediterranean cultures have perceived northern Europeans as efficient but cold and preoccupied with punctuality (Triandis, 1981). People from time-conscious Japan—where bank clocks keep exact time, pedestrians walk briskly, and postal clerks fill requests speedily—have found themselves growing impatient when visiting Indonesia, where clocks keep less accurate time and the pace of life is more leisurely (Levine & Norenzayan, 1999). Someone from the European community, which requires 20 paid vacation days each year, may also experience culture shock when working in the United States, which does not guarantee workers any paid vacation (Ray et al., 2013).

Variation Over Time

Like biological creatures, cultures vary and compete for resources, and thus evolve over time (Mesoudi, 2009). Consider how rapidly cultures may change. English poet Geoffrey Chaucer (1342–1400) is separated from a modern Briton by only 20 generations, but the two would have great difficulty speaking. In the thin slice of history since 1960, most Western cultures have changed with remarkable speed. Middle-class people fly to places they once only read about. They enjoy the convenience of air-conditioned housing, online shopping, anywhere-anytime electronic communication, and—enriched by doubled per-person real income—eating out more than twice as often as did their grandparents back in the culture of 1960. Many minority groups enjoy expanded human rights. And, with greater economic independence, today’s women more often marry for love and less often endure abusive relationships.

157

But some changes seem not so wonderfully positive. Had you fallen asleep in the United States in 1960 and awakened today, you would open your eyes to a culture with more divorce and depression. You would also find North Americans—like their counterparts in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand—spending more hours at work, fewer hours with friends and family, and fewer hours asleep (BLS, 2011; Putnam, 2000).

Whether we love or loathe these changes, we cannot fail to be impressed by their breathtaking speed. And we cannot explain them by changes in the human gene pool, which evolves far too slowly to account for high-speed cultural transformations. Cultures vary. Cultures change. And cultures shape our lives.

Culture and the Self

4-13 How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ in their values and goals?

Imagine that someone ripped away your social connections, making you a solitary refugee in a foreign land. How much of your identity would remain intact?

individualism giving priority to one’s own goals over group goals and defining one’s identity in terms of personal attributes rather than group identifications.

If you are an individualist, a great deal of your identity would remain intact. You would have an independent sense of “me,” and an awareness of your unique personal convictions and values. Individualists give higher priority to personal goals. They define their identity mostly in terms of personal traits. They strive for personal control and individual achievement.

Individualism is valued in most areas of North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. The United States is mostly an individualist culture. Founded by settlers who wanted to differentiate themselves from others, Americans have cherished the “pioneer” spirit (Kitayama et al., 2010). Some 85 percent of Americans say it is possible “to pretty much be who you want to be” (Sampson, 2000).

Individualists share the human need to belong. They join groups. But they are less focused on group harmony and doing their duty to the group (Brewer & Chen, 2007). Being more self-contained, individualists move in and out of social groups more easily. They feel relatively free to switch places of worship, switch jobs, or even leave their extended families and migrate to a new place. Marriage is often for as long as they both shall love.

collectivism giving priority to the goals of one’s group (often one’s extended family or work group) and defining one’s identity accordingly.

Although individuals within cultures vary, different cultures emphasize either individualism or collectivism. If set adrift in a foreign land as a collectivist, you might experience a greater loss of identity. Cut off from family, groups, and loyal friends, you would lose the connections that have defined who you are. Group identifications provide a sense of belonging, a set of values, and an assurance of security in collectivist cultures. In return, collectivists have deeper, more stable attachments to their groups—their family, clan, or company. Elders receive great respect. In some collectivist cultures, disrespecting family elders violates the law. The Law of the People’s Republic of China on Protection of the Rights and Interests of the Elderly states that parents aged 60 or above can sue their sons and daughters if they fail to provide “for the elderly, taking care of them and comforting them, and cater[ing] to their special needs.”

Collectivists are like athletes who take more pleasure in their team’s victory than in their own performance. They find satisfaction in advancing their groups’ interests, even at the expense of personal needs. Preserving group spirit and avoiding social embarrassment are important goals. Collectivists therefore avoid direct confrontation, blunt honesty, and uncomfortable topics. They value humility, not self-importance (Bond et al., 2012). Instead of dominating conversations, collectivists hold back and display shyness when meeting strangers (Cheek & Melchior, 1990). When the priority is “we,” not “me,” that individualized latte—“decaf, single shot, skinny, extra hot”—that feels so good in a North American coffee shop might sound like a selfish demand in Seoul (Kim & Markus, 1999).

“One needs to cultivate the spirit of sacrificing the little me to achieve the benefits of the big me.”

Chinese saying

158

To be sure, there is diversity within cultures. Within many countries, there are also distinct subcultures related to one’s religion, economic status, and region (Cohen, 2009). In China, greater collectivist thinking occurs in provinces that produce large amounts of rice, a difficult-to-grow crop that often involves cooperation between groups of people (Talhelm et al., 2014). In collectivist Japan, a spirit of individualism marks the “northern frontier” island of Hokkaido (Kitayama et al., 2006). And even in the most individualist countries, some people have collectivist values. But in general, people (especially men) in competitive, individualist cultures have more personal freedom, are less geographically bound to their families, enjoy more privacy, and take more pride in personal achievements (TABLE 4.2).

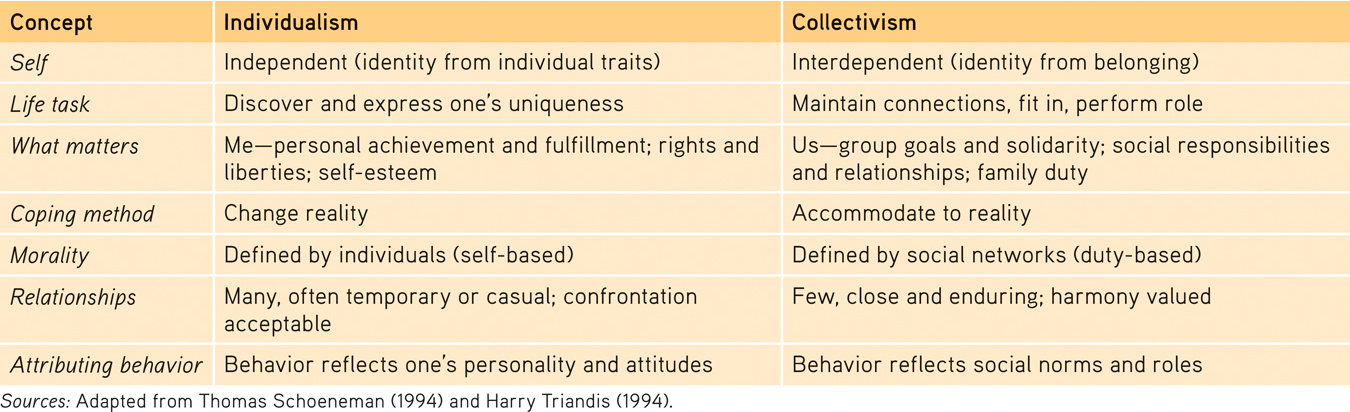

Table 4.2

Table 4.2Value Contrasts Between Individualism and Collectivism

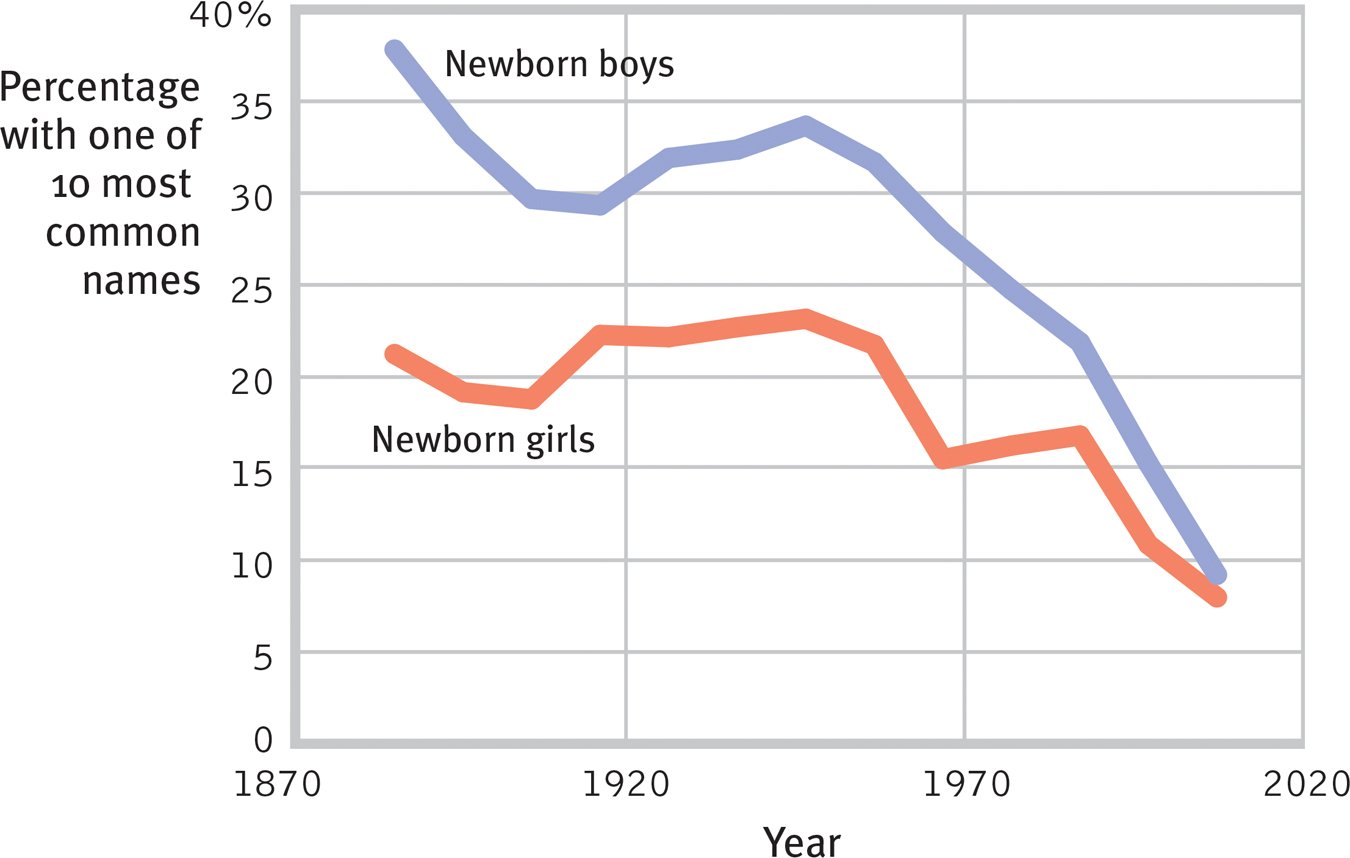

Individualists even prefer unusual names, as psychologist Jean Twenge noticed while seeking a name for her first child. Over time, the most common American names listed by year on the U.S. Social Security baby names website were becoming less desirable. When she and her colleagues (2010) analyzed the first names of 325 million American babies born between 1880 and 2007, they confirmed this trend. As FIGURE 4.6 illustrates, the percentage of boys and girls given one of the 10 most common names for their birth year has plunged, especially in recent years. Even within the United States, parents from more recently settled states (for example, Utah and Arizona) give their children more distinct names compared with parents who live in more established states (for example, New York and Massachusetts) (Varnum & Kitayama, 2011).

Figure 4.6

Figure 4.6A child like no other Americans’ individualist tendencies are reflected in their choice of names for their babies. In recent years, the percentage of American babies receiving one of that year’s 10 most common names has plunged. (Data from Twenge et al., 2010.)

159

The individualist–collectivist divide appeared in reactions to medals received during the 2000 and 2002 Olympic games. U.S. gold medal winners and the U.S. media covering them attributed the achievements mostly to the athletes themselves (Markus et al., 2006). “I think I just stayed focused,” explained swimming gold medalist Misty Hyman. “It was time to show the world what I could do. I am just glad I was able to do it.” Japan’s gold medalist in the women’s marathon, Naoko Takahashi, had a different explanation: “Here is the best coach in the world, the best manager in the world, and all of the people who support me—all of these things were getting together and became a gold medal.” Even when describing friends, Westerners tend to use trait-describing adjectives (“she is helpful”), whereas East Asians more often use verbs that describe behaviors in context (“she helps her friends”) (Heine & Buchtel, 2009; Maass et al., 2006).

There has been more loneliness, divorce, homicide, and stress-related disease in individualist cultures (Popenoe, 1993; Triandis et al., 1988). Demands for more romance and personal fulfillment in marriage can subject relationships to more pressure (Dion & Dion, 1993). In one survey, “keeping romance alive” was rated as important to a good marriage by 78 percent of U.S. women but only 29 percent of Japanese women (American Enterprise, 1992). In China, love songs have often expressed enduring commitment and friendship (Rothbaum & Tsang, 1998): “We will be together from now on…. I will never change from now to forever.”

As cultures evolve, some trends weaken and others grow stronger. In Western cultures, individualism increased strikingly over the last century. This trend reached a new high in 2012, when U.S. high school and college students reported the greatest-ever interest in obtaining benefits for themselves and the lowest-ever concern for others (Twenge et al., 2012).

What predicts changes in one culture over time, or between differing cultures? Social history matters. In Western cultures, individualism and independence have been fostered by voluntary migration, a capitalist economy, and a sparsely populated, challenging environment (Kitayama et al., 2009, 2010; Varnum et al., 2010). Might biology also play a role? In search of biological underpinnings to such cultural differences—remembering that everything psychological is also biological—a new subfield, cultural neuroscience, is studying how neurobiology and cultural traits influence each other (Chiao et al., 2013). One study compared collectivists’ and individualists’ brain activity when viewing other people in distress. The brain scans suggested that collectivists experienced greater emotional pain when exposed to others’ distress (Cheon et al., 2011). As we will see over and again, biological, psychological, and social-cultural perspectives intersect. We are biopsychosocial creatures.

160

Culture and Child Raising

Child-raising practices reflect not only individual values, but also cultural values that vary across time and place. Should children be independent or obedient? If you live in a Westernized culture, you likely prefer independence. “You are responsible for yourself,” Western families and schools tell their children. “Follow your conscience. Be true to yourself. Discover your gifts. Think through your personal needs.” A half-century ago and more, Western cultural values placed greater priority on obedience, respect, and sensitivity to others (Alwin, 1990; Remley, 1988). “Be true to your traditions,” parents then taught their children. “Be loyal to your heritage and country. Show respect toward your parents and other superiors.” Cultures can change.

Children across place and time have thrived under various child-raising systems. Many Americans now give children their own bedrooms and entrust them to day care. Upper-class British parents traditionally handed off routine caregiving to nannies, then sent their 10-year-olds away to boarding school. These children generally grew up to be pillars of British society.

Many Asians and Africans live in cultures that value emotional closeness. Infants and toddlers may sleep with their mothers and spend their days close to a family member (Morelli et al., 1992; Whiting & Edwards, 1988). These cultures encourage a strong sense of family self—a feeling that what shames the child shames the family, and what brings honor to the family brings honor to the self.

In the African Gusii society, babies nurse freely but spend most of the day on their mother’s back—with lots of body contact but little face-to-face and language interaction. When the mother becomes pregnant again, the toddler is weaned and handed over to someone else, often an older sibling. Westerners may wonder about the negative effects of this lack of verbal interaction, but then the African Gusii may in turn wonder about Western mothers pushing their babies around in strollers and leaving them in playpens (Small, 1997). Such diversity in child raising cautions us against presuming that our culture’s way is the only way to raise children successfully.

Developmental Similarities Across Groups

Mindful of how others differ from us, we often fail to notice the similarities predisposed by our shared biology. One 49-country study revealed smaller than expected nation-to-nation differences in personality traits, such as conscientiousness and extraversion (Terracciano et al., 2006). National stereotypes exaggerate differences that, although real, are modest: Australians see themselves as outgoing, German-speaking Swiss see themselves as conscientious, and Canadians see themselves as agreeable. Actually, compared with the person-to-person differences within groups, between-group differences are small. Regardless of our culture, we humans are more alike than different. We share the same life cycle. We speak to our infants in similar ways and respond similarly to their coos and cries (Bornstein et al., 1992a,b). All over the world, the children of warm and supportive parents feel better about themselves and are less hostile than are the children of punitive and rejecting parents (Rohner, 1986; Scott et al., 1991).

161

Even differences within a culture, such as those sometimes attributed to race, are often easily explained by an interaction between our biology and our culture. David Rowe and his colleagues (1994, 1995) illustrated this with an analogy: Black men tend to have higher blood pressure than White men. Suppose that (1) in both groups, salt consumption correlates with blood pressure, and (2) salt consumption is higher among Black men than among White men. The blood pressure “race difference” might then actually be, at least partly, a diet difference—a cultural preference for certain foods.

“When [someone] has discovered why men in Bond Street wear black hats he will at the same moment have discovered why men in Timbuctoo wear red feathers.”

G. K. Chesterton, Heretics, 1905

And that, said Rowe and his colleagues, parallels psychological findings. Although Latino, Asian, Black, White, and Native Americans differ in school achievement and delinquency, the differences are “no more than skin deep.” To the extent that family structure, peer influences, and parental education predict behavior in one of these ethnic groups, they do so for the others as well.

So as members of different ethnic and cultural groups, we may differ in surface ways. But as members of one species we seem subject to the same psychological forces. Our languages vary, yet they reflect universal principles of grammar. Our tastes vary, yet they reflect common principles of hunger. Our social behaviors vary, yet they reflect pervasive principles of human influence. Cross-cultural research helps us appreciate both our cultural diversity and our human similarity.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ?

Individualists give priority to personal goals over group goals and tend to define their identity in terms of their own personal attributes. Collectivists give priority to group goals over individual goals and tend to define their identity in terms of group identifications.

Gender Development

4-14 How does the meaning of gender differ from the meaning of sex?

sex in psychology, the biologically influenced characteristics by which people define males and females.

We humans share an irresistible urge to organize our worlds into simple categories. Among the ways we classify people—as tall or short, younger or older, smart or dull—one stands out. Immediately after your birth (or perhaps even before), everyone wanted to know, “Boy or girl?” Your parents may have offered clues with pink or blue clothing. The simple answer described your sex, your biological status, defined by your chromosomes and anatomy. For most people, those biological traits help define their gender, their culture’s expectations about what it means to be male or female.

gender in psychology, the socially influenced characteristics by which people define men and women.

Our gender is the product of the interplay among our biological dispositions, our developmental experiences, and our current situations (Eagly & Wood, 2013). Before we consider that interplay in more detail, let’s take a closer look at some ways that males and females are both similar and different.

Similarities and Differences

4-15 What are some ways in which males and females tend to be alike and to differ?

Whether male or female, each of us receives 23 chromosomes from our mother and 23 from our father. Of those 46 chromosomes, 45 are unisex. Our similar biology helped our evolutionary ancestors face similar adaptive challenges. Both men and women needed to survive, reproduce, and avoid predators, and so today we are in most ways alike. Tell me whether you are male or female and you give me no clues to your vocabulary, happiness, or ability to see, hear, learn, and remember. Women and men, on average, have comparable creativity and intelligence and feel the same emotions and longings. Our “opposite” sex is, in reality, our very similar sex.

Pink and blue baby outfits illustrate how cultural norms vary and change. “The generally accepted rule is pink for the boy and blue for the girl,” declared the Earnshaw’s Infants’ Department in June of 1918 (Frassanito & Pettorini, 2008). “The reason is that pink being a more decided and stronger color is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girls.”

162

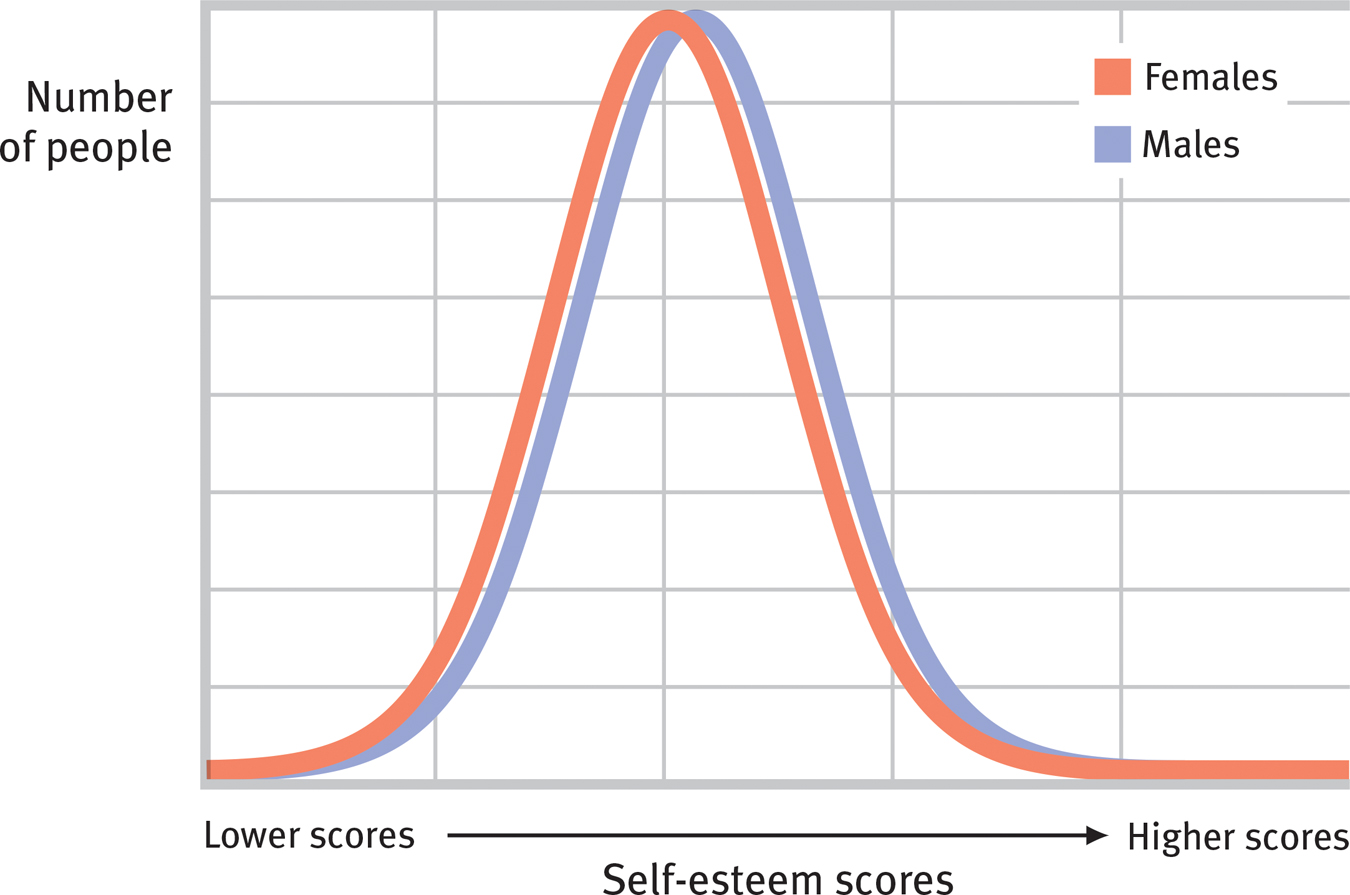

Figure 4.7

Figure 4.7Much ado about a small difference in self-esteem These two normal distributions differ by the approximate magnitude (0.21 standard deviation) of the sex difference in self-esteem, averaged over all available samples (Hyde, 2005). Moreover, such comparisons illustrate differences between the average female and male. The variation among individual females greatly exceeds this difference, as it also does among individual males.

But in some areas, males and females do differ, and differences command attention. Some much talked-about differences (like the difference in self-esteem shown in FIGURE 4.7) are actually quite modest. Other differences are more striking. The average woman enters puberty about a year earlier than the average man, and her life span is 5 years longer. She expresses emotions more freely, can detect fainter odors, and receives offers of help more often. She also has twice the risk of developing depression and anxiety and 10 times the risk of developing an eating disorder. Yet the average man is 4 times more likely to die by suicide or to develop an alcohol use disorder. His “more likely” list includes autism spectrum disorder, color-blindness, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). And as an adult, he is more at risk for antisocial personality disorder. Male or female, each has its own share of risks.

Let’s take a closer look at three areas—aggression, social power, and social connectedness—in which the average male and female differ.

aggression any physical or verbal behavior intended to harm someone physically or emotionally.

Aggression To a psychologist, aggression is any physical or verbal behavior intended to hurt someone physically or emotionally. Think of some aggressive people you have heard about. Are most of them men? Men generally admit to more aggression. They also commit more extreme physical violence (Bushman & Huesmann, 2010). In romantic relationships between men and women, minor acts of physical aggression, such as slaps, are roughly equal—but extremely violent acts are mostly committed by men (Archer, 2000; Johnson, 2008).

Laboratory experiments have demonstrated gender differences in aggression. Men have been more willing to blast people with what they believed was intense and prolonged noise (Bushman et al., 2007). And outside the laboratory, men—worldwide—commit more violent crime (Antonaccio et al., 2011; Caddick & Porter, 2012; Frisell et al., 2012). They also take the lead in hunting, fighting, warring, and supporting war (Liddle et al., 2012; Wood & Eagly, 2002, 2007).

relational aggression an act of aggression (physical or verbal) intended to harm a person’s relationship or social standing.

Here’s another question: Think of examples of people harming others by passing along hurtful gossip, or by shutting someone out of a social group or situation. Were most of those people men? Perhaps not. Those behaviors are acts of relational aggression, and women are slightly more likely than men to commit them (Archer, 2004, 2007, 2009).

Social Power Imagine walking into a job interview. You sit down and peer across the table at your two interviewers. The unsmiling person on the left oozes self-confidence and independence and maintains steady eye contact with you. The person on the right gives you a warm, welcoming smile but makes less eye contact and seems to expect the other interviewer to take the lead.

Which interviewer is male?

If you said the person on the left, you’re not alone. Around the world, from Nigeria to New Zealand, people have perceived gender differences in power (Williams & Best, 1990). Indeed, in most societies men do place more importance on power and achievement and are socially dominant (Schwartz & Rubel-Lifschitz, 2009):

163

- When groups form, whether as juries or companies, leadership tends to go to males (Colarelli et al., 2006). And when salaries are paid, those in traditionally male occupations receive more.

- When people run for election, women who appear hungry for political power more than their equally power-hungry male counterparts experience less success (Okimoto & Brescoll, 2010). And when elected, political leaders usually are men, who held 78 percent of the seats in the world’s governing parliaments in 2014 (IPU, 2014).

Men and women also lead differently. Men tend to be more directive, telling people what they want and how to achieve it. Women tend to be more democratic, more welcoming of others’ input in decision making (Eagly & Carli, 2007; van Engen & Willemsen, 2004). When interacting, men have been more likely to offer opinions, women to express support (Aries, 1987; Wood, 1987). In everyday behavior, men tend to act as powerful people often do: talking assertively, interrupting, initiating touches, and staring. And they smile and apologize less (Leaper & Ayres, 2007; Major et al., 1990; Schumann & Ross, 2010). Such behaviors help sustain men’s greater social power.

Women’s 2011 representations in national parliaments ranged from 13 percent in the Pacific region to 42 percent in Scandinavia (IPU, 2014).

Social Connectedness Whether male or female, we all have a need to belong, though we may satisfy this need in different ways (Baumeister, 2010). Males tend to be independent. Even as children, males typically form large play groups. Boys’ games brim with activity and competition, with little intimate discussion (Rose & Rudolph, 2006). As adults, men enjoy doing activities side by side, and they tend to use conversation to communicate solutions (Tannen, 1990; Wright, 1989). When asked a difficult question—“Do you have any idea why the sky is blue?”—men are more likely than women to hazard answers than to admit they don’t know, a phenomenon researchers have called the male answer syndrome (Giuliano et al., 1998).

Question: Why does it take 200 million sperm to fertilize one egg?

Answer: Because they won’t stop for directions.

Females tend to be more interdependent. In childhood, girls usually play in small groups, often with one friend. They compete less and imitate social relationships more (Maccoby, 1990; Roberts, 1991). Teen girls spend more time with friends and less time alone (Wong & Csikszentmihalyi, 1991). In late adolescence, they spend more time on social-networking Internet sites (Pryor et al., 2007, 2011). As adults, women take more pleasure in talking face to face, and they tend to use conversation more to explore relationships.

Brain scans suggest that women’s brains are better wired to improve social relationships, and men’s brains to connect perception with action (Ingalhalikar et al., 2013). The communication style gender difference is apparent even in electronic communication. In one New Zealand study of student e-mails, people correctly guessed two-thirds of the time whether the author was male or female (Thomson & Murachver, 2001). The gap appears in phone-based communications, too. How many texts does an American teen send and receive each day? Girls average 100, boys only 50 (Lenhart, 2012). In France, women have made 63 percent of phone calls and, when talking to a woman, stayed connected longer (7.2 minutes) than men did when talking to other men (4.6 minutes) (Smoreda & Licoppe, 2000).

Do such findings mean that women are just more talkative? No. In another study, researchers counted the number of words 396 college students spoke in an average day (Mehl et al., 2007). Not surprisingly, the participants’ talkativeness varied enormously—by 45,000 words between the most and least talkative. (How many words would you guess you speak a day?) Contrary to stereotypes of wordy women, both men and women averaged about 16,000 words daily.

The words we use may not peg women or men as more talkative, but those words do open windows on our interests. Worldwide, women’s interests and vocations tilt more toward people and less toward things (Eagly, 2009; Lippa, 2005, 2006, 2008). In one analysis of over 700 million words collected from Facebook messages, women used more family-related words, whereas men used more work-related words (Schwartz et al., 2013). More than a half-million people’s responses to various interest inventories reveal that “men prefer working with things and women prefer working with people” (Su et al., 2009). On entering American colleges, men are seven times more likely than women to express interest in computer science (Pryor et al., 2011).

164

In the workplace, women are less often driven by money and status and more apt to opt for reduced work hours (Pinker, 2008). In the home, they are five times more likely than men to claim primary responsibility for taking care of children (Time, 2009). Women’s emphasis on caring helps explain another interesting finding: Although 69 percent of people have said they have a close relationship with their father, 90 percent said they feel close to their mother (Hugick, 1989). When searching for understanding from someone who will share their worries and hurts, people usually turn to women. Both men and women have reported their friendships with women as more intimate, enjoyable, and nurturing (Kuttler et al., 1999; Rubin, 1985; Sapadin, 1988).

Bonds and feelings of support are even stronger among women than among men (Rossi & Rossi, 1993). Women’s ties—as mothers, daughters, sisters, aunts, and grandmothers—bind families together. As friends, women talk more often and more openly (Berndt, 1992; Dindia & Allen, 1992). “Perhaps because of [women’s] greater desire for intimacy,” reported Joyce Benenson and colleagues (2009), first-year college and university women are twice as likely as men to change roommates. How do they cope with their own stress? Compared with men, women are more likely to turn to others for support. They are said to tend and befriend (Tamres et al., 2002; Taylor, 2002).

As empowered people generally do, men value freedom and self-reliance, which may help explain why men of all ages, worldwide, are less religious and pray less (Benson, 1992; Stark, 2002). Men also dominate the ranks of professional skeptics. All 10 winners and 14 runners-up on the Skeptical Inquirer list of outstanding twentieth-century rationalist skeptics were men. In one Skeptics Society survey, nearly 4 in 5 respondents were men (Shermer, 1999). And in the Science and the Paranormal section of the 2010 Prometheus Books catalog (from the leading publisher of skepticism), one could find 98 male and 4 female authors. (Women are far more likely to author books on spirituality.)

The gender gap in both social connectedness and power peaks in late adolescence and early adulthood—the prime years for dating and mating. Teenage girls become less assertive and more flirtatious, and boys appear more dominant and less expressive. Gender differences in attitudes and behavior often peak after the birth of a first child. Mothers especially may become more traditional (Ferriman et al., 2009; Katz-Wise et al., 2010). By age 50, most parent-related gender differences subside. Men become less domineering and more empathic, and women—especially those with paid employment—become more assertive and self-confident (Kasen et al., 2006; Maccoby, 1998).

So, although women and men are more alike than different, there are some behavior differences between the average woman and man. Are such differences dictated by our biology? Shaped by our cultures and other experiences? Do we vary in the extent to which we are male or female? Read on.

“In the long years liker must they grow; The man be more of woman, she of man.”

Alfred Lord Tennyson, The Princess, 1847

165

The Nature of Gender: Our Biological Sex

4-16 How do sex hormones influence prenatal and adolescent sexual development, and what is a disorder of sexual development?

Men and women employ similar solutions when faced with challenges: sweating to cool down, guzzling an energy drink or coffee to get going in the morning, or finding darkness and quiet to sleep. When looking for a mate, men and women also prize many of the same traits. They prefer having a mate who is “kind,” “honest,” and “intelligent.” But according to evolutionary psychologists, in mating-related domains, guys act like guys whether they’re chimpanzees or elephants, rural peasants or corporate presidents (Geary, 2010).

Biology does not dictate gender, but it can influence it in two ways:

- Genetically—males and females have differing sex chromosomes.

- Physiologically—males and females have differing concentrations of sex hormones, which trigger other anatomical differences.

These two sets of influences began to form you long before you were born, when your tiny body started developing in ways that determined your sex.

X chromosome the sex chromosome found in both men and women. Females have two X chromosomes; males have one. An X chromosome from each parent produces a female child.

Prenatal Sexual Development Six weeks after you were conceived, you and someone of the other sex looked much the same. Then, as your genes kicked in, your biological sex—determined by your twenty-third pair of chromosomes (the two sex chromosomes)—became more apparent. Whether you are male or female, your mother’s contribution to that chromosome pair was an X chromosome. From your father, you received the one chromosome out of 46 that is not unisex—either another X chromosome, making you female, or a Y chromosome, making you male.

Y chromosome the sex chromosome found only in males. When paired with an X chromosome from the mother, it produces a male child.

testosterone the most important of the male sex hormones. Both males and females have it, but the additional testosterone in males stimulates the growth of the male sex organs during the fetal period, and the development of the male sex characteristics during puberty.

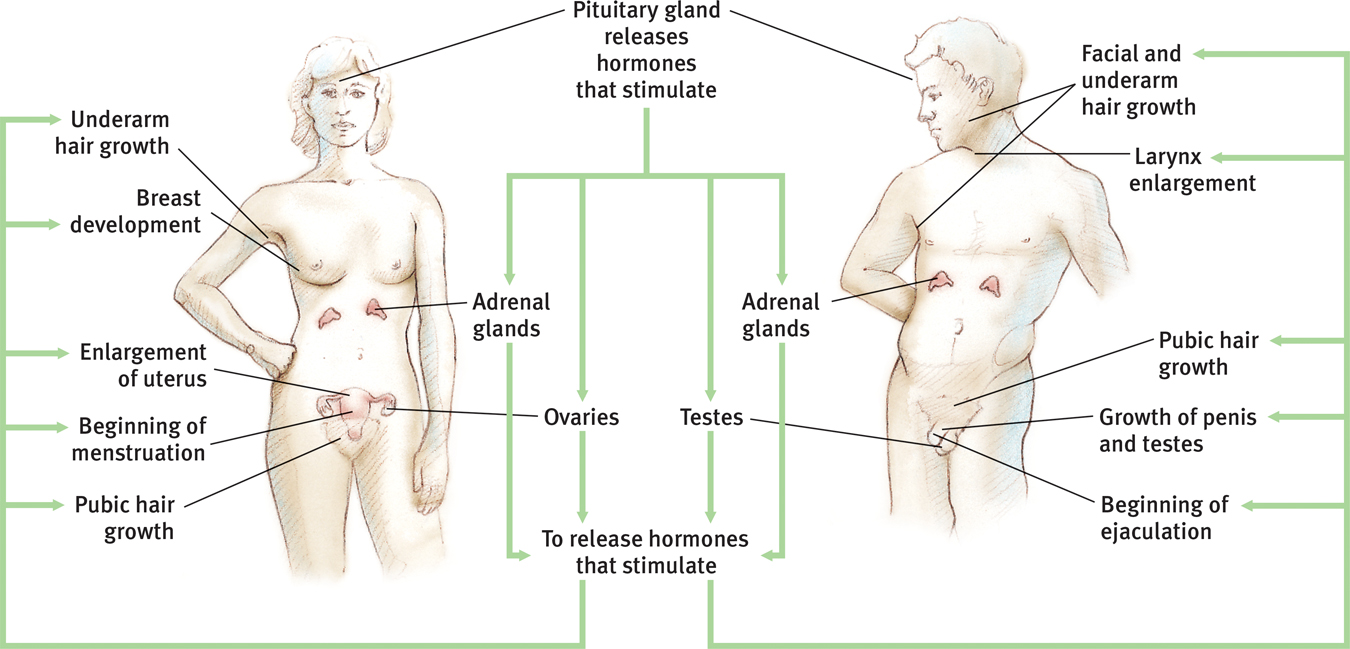

About seven weeks after conception, a single gene on the Y chromosome throws a master switch, which triggers the testes to develop and to produce testosterone, the principal male hormone that promotes development of male sex organs. (Females also have testosterone, but less of it.) The male’s greater testosterone output starts the development of external male sex organs at about the seventh week.

Later, during the fourth and fifth prenatal months, sex hormones bathe the fetal brain and influence its wiring. Different patterns for males and females develop under the influence of the male’s greater testosterone and the female’s ovarian hormones (Hines, 2004; Udry, 2000). Male-female differences emerge in brain areas with abundant sex hormone receptors (Cahill, 2005).

puberty the period of sexual maturation, when a person becomes capable of reproducing.

Adolescent Sexual Development A flood of hormones triggers another period of dramatic physical change during adolescence, when boys and girls enter puberty. In this two-year period of rapid sexual maturation, pronounced male-female differences occur. A variety of changes begin at about age 11 in girls and at about age 12 in boys, though the subtle beginnings of puberty, such as enlarging testes, appear earlier (Herman-Giddens et al., 2012). A year or two before the physical changes are visible, girls and boys often feel the first stirrings of attraction toward someone of the other or their own sex (McClintock & Herdt, 1996).

primary sex characteristics the body structures (ovaries, testes, and external genitalia) that make sexual reproduction possible.

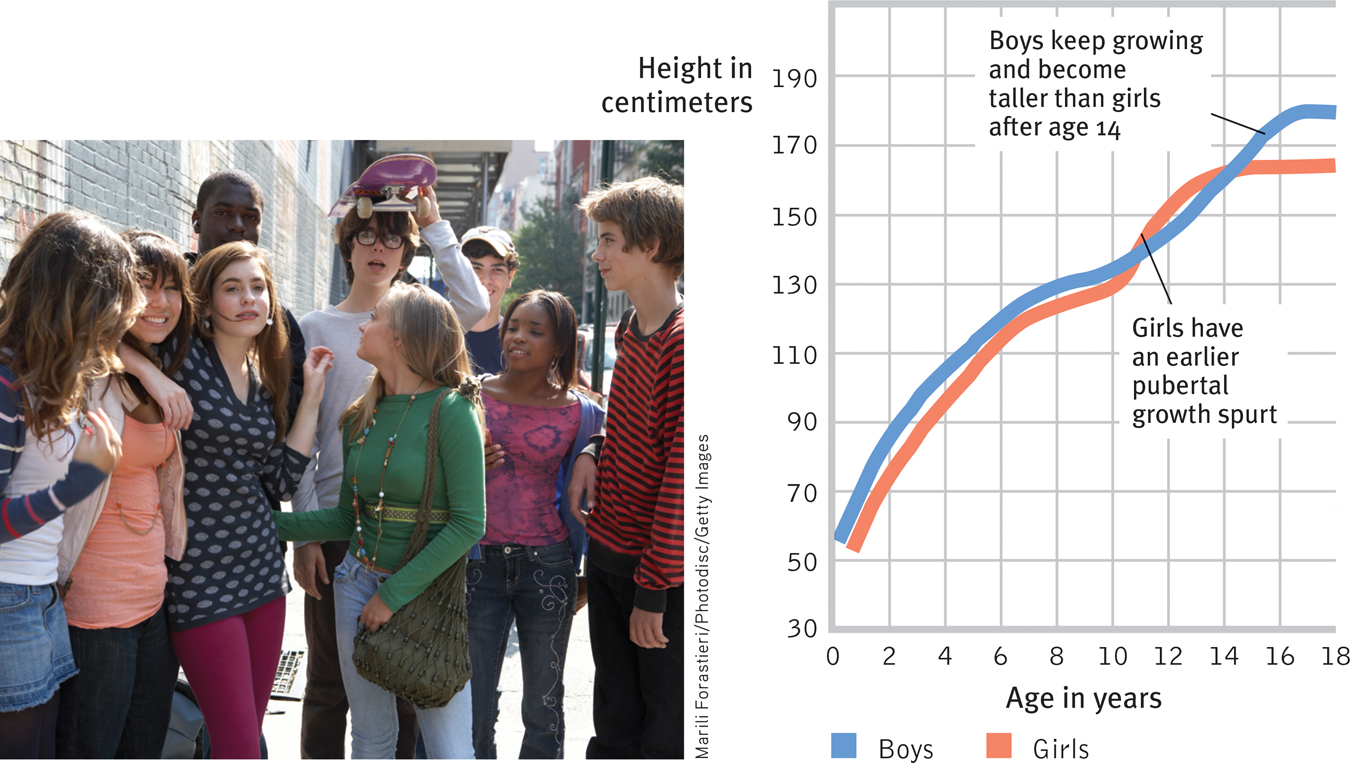

Girls’ slightly earlier entry into puberty can at first propel them to greater height than boys of the same age (FIGURE 4.8 below). But boys catch up when they begin puberty, and by age 14, they are usually taller than girls. During these growth spurts, the primary sex characteristics—the reproductive organs and external genitalia—develop dramatically. So do the secondary sex characteristics. Girls develop breasts and larger hips. Boys’ facial hair begins growing and their voices deepen. Pubic and underarm hair emerges in both girls and boys (FIGURE 4.9 below).

secondary sex characteristics nonreproductive sexual traits, such as female breasts and hips, male voice quality, and body hair.

Figure 4.8

Figure 4.8Height differences Throughout childhood, boys and girls are similar in height. At puberty, girls surge ahead briefly, but then boys typically overtake them at about age 14. (Data from Tanner, 1978.) Studies suggest that sexual development and growth spurts are now beginning somewhat earlier than was the case a half-century ago (Herman-Giddens et al., 2001).

Figure 4.9

Figure 4.9Body changes at puberty At about age 11 in girls and age 12 in boys, a surge of hormones triggers a variety of visible physical changes.

166

Pubertal boys may not at first like their sparse beard. (But then it grows on them.)

spermarche [sper-MAR-key] first ejaculation.

For boys, puberty’s landmark is the first ejaculation, which often occurs first during sleep (as a “wet dream”). This event, called spermarche (sper-MAR-key), usually happens by about age 14.

menarche [meh-NAR-key] the first menstrual period.

In girls, the landmark is the first menstrual period (menarche—meh-NAR-key), usually within a year of age 12½ (Anderson et al., 2003). Early menarche is more likely following stresses related to father absence, sexual abuse, insecure attachments, or a history of a mother’s smoking during pregnancy (DelPriore & Hill, 2013; Rickard et al., 2014; Shrestha et al., 2011). In various countries, girls are developing breasts earlier (sometimes before age 10) and reaching puberty earlier than in the past. Suspected triggers include increased body fat, diets filled with hormone-mimicking chemicals, and possibly greater stress due to family disruption (Biro et al., 2010, 2012; Herman-Giddens, 2012).

167

Girls prepared for menarche usually experience it positively (Chang et al., 2009). Most women recall their first menstrual period with mixed emotions—pride, excitement, embarrassment, and apprehension (Greif & Ulman, 1982; Woods et al., 1983). Men report mostly positive emotional reactions to spermarche (Fuller & Downs, 1990).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Adolescence is marked by the onset of ______________.

puberty

For a 7-minute discussion of our sexual development, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Gender Development.

For a 7-minute discussion of our sexual development, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Gender Development.

disorder of sexual development an inherited condition that involves unusual development of sex chromosomes and anatomy.

Sexual Development Variations Sometimes nature blurs the biological line between males and females. When a fetus is exposed to unusual levels of sex hormones, or is especially sensitive to those hormones, the individual may develop a disorder of sexual development, with chromosomes or anatomy not typically male or female. A genetic male may be born with normal male hormones and testes but no penis or a very small one.

In the past, medical professionals often recommended sex-reassignment surgery to create an unambiguous identity for some children with this condition. One study reviewed 14 cases of boys who had undergone early surgery and been raised as girls. Of those cases, 6 had later declared themselves male, 5 were living as females, and 3 reported an unclear male or female identity (Reiner & Gearhart, 2004).

Sex-reassignment surgery can create confusion and distress among those not born with a disorder of sexual development. In one famous case, a little boy lost his penis during a botched circumcision. His parents followed a psychiatrist’s advice to raise him as a girl rather than as a damaged boy. Alas, “Brenda” Reimer was not like most other girls. “She” didn’t like dolls. She tore her dresses with rough-and-tumble play. At puberty she wanted no part of kissing boys. Finally, Brenda’s parents explained what had happened, whereupon “Brenda” immediately rejected the assigned female identity. He cut his hair and chose a male name, David. He eventually married a woman and became a stepfather. And, sadly, he later committed suicide (Colapinto, 2000).

The bottom line: “Sex matters,” concluded the National Academy of Sciences (2001). Sex-related genes and physiology “result in behavioral and cognitive differences between males and females.” Yet environmental factors matter too, as we will see next. Nature and nurture work together.

The Nurture of Gender: Our Culture and Experiences

4-17 How do gender roles and gender identity differ?

For many people, biological sex and gender coexist in harmony. Biology draws the outline, and culture paints the details. The physical traits that define us as biological males or females are the same worldwide. But the gender traits that define how men (or boys) and women (or girls) should act, interact, or feel about themselves may differ from one place to another (APA, 2009).

role a set of expectations (norms) about a social position, defining how those in the position ought to behave.

Gender Roles Cultures shape our behaviors by defining how we ought to behave in a particular social position, or role. We can see this shaping power in gender roles—the social expectations that guide our behavior as men or as women. Gender roles shift over time. A century ago, North American women could not vote in national elections, serve in the military, or divorce a husband without cause. And if a woman worked for pay outside the home, she would more likely have been a midwife or a seamstress, rather than a surgeon or a fashion designer.

gender role a set of expected behaviors, attitudes, and traits for males or for females.

168

Gender roles can change dramatically in a thin slice of history. At the beginning of the twentieth century, only one country in the world—New Zealand—granted women the right to vote (Briscoe, 1997). Today, worldwide, only Saudi Arabia denies women the right to vote. Even there, the culture shows signs of shifting toward women’s voting rights (Alsharif, 2011). More U.S. women than men now graduate from college, and nearly half the work force is female (Fry & Cohn, 2010). The modern economy has produced jobs that rely not on brute strength but on social intelligence, open communication, and the ability to sit still and focus (Rosin, 2010). What changes might the next hundred years bring?

Gender roles also vary from one place to another. Nomadic societies of food-gathering people have had little division of labor by sex. Boys and girls receive much the same upbringing. In agricultural societies, where women work in the nearby fields and men roam while herding livestock, cultures have shaped children to assume more distinct gender roles (Segall et al., 1990; Van Leeuwen, 1978).

Take a minute to check your own gender expectations. Would you agree that “When jobs are scarce, men should have more rights to a job”? In the United States, Britain, and Spain, barely over 12 percent of adults agree. In Nigeria, Pakistan, and India, about 80 percent of adults agree (Pew, 2010). We’re all human, but my how our views differ. Australia and the Scandinavian countries offer the greatest gender equity, Middle Eastern and North African countries the least (Social Watch, 2006).

gender identity our sense of being male, female, or a combination of the two.

How Do We Learn Gender? A gender role describes how others expect us to think, feel, and act. Our gender identity is our personal sense of being male, female, or a combination of the two. How do we develop that personal viewpoint?

social learning theory the theory that we learn social behavior by observing and imitating and by being rewarded or punished.

Social learning theory assumes that we acquire our gender identity in childhood, by observing and imitating others’ gender-linked behaviors and by being rewarded or punished for acting in certain ways. (“Tatiana, you’re such a good mommy to your dolls”; “Big boys don’t cry, Armand.”) Some critics think there’s more to gender identity than imitating parents and being repeatedly rewarded for certain responses. They point out that gender typing—taking on the traditional male or female role—varies from child to child (Tobin et al., 2010). No matter how much parents encourage or discourage traditional gender behavior, children may drift toward what feels right to them. Some organize themselves into “boy worlds” and “girl worlds,” each guided by rules. Others seem to prefer androgyny: A blend of male and female roles feels right to them. Androgyny has benefits. Androgynous people are more adaptable. They show greater flexibility in behavior and career choices (Bem, 1993). They tend to be more resilient and self-accepting, and they experience less depression (Lam & McBride-Chang, 2007; Mosher & Danoff-Burg, 2008; Ward, 2000).

gender typing the acquisition of a traditional masculine or feminine role.

androgyny displaying both traditional masculine and feminine psychological characteristics.

169

How we feel matters, but so does how we think. Early in life, we form schemas, or concepts that help us make sense of our world. Our gender schemas organized our experiences of male-female characteristics and helped us think about our gender identity, about who we are (Bem, 1987, 1993; Martin et al., 2002). Our parents help to transmit their culture’s views on gender. In one analysis of 43 studies, parents with traditional gender schemas were more likely to have gender-typed children who shared their culture’s expectations about how males and females should act (Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002).

As a young child, you (like other children) were a “gender detective” (Martin & Ruble, 2004). Before your first birthday, you knew the difference between a male and female voice or face (Martin et al., 2002). After you turned 2, language forced you to label the world in terms of gender. If you are an English speaker, you learned to classify people as he and she. If you are a French speaker, you learned also to classify objects as masculine (“le train”) or feminine (“la table”).

Once children grasp that two sorts of people exist—and that they are of one sort—they search for clues about gender. In every culture, people communicate their gender in many ways. Their gender expression drops hints not only in their language but also in their clothing, interests, and possessions. Having divided the human world in half, 3-year-olds will then like their own kind better and seek them out for play. “Girls,” they may decide, are the ones who watch Dora the Explorer and have long hair. “Boys” watch battles from Kung Fu Panda and don’t wear dresses. Armed with their newly collected “proof,” they then adjust their behaviors to fit their concept of gender. These rigid stereotypes peak at about age 5 or 6. If the new neighbor is a boy, a 6-year-old girl may assume that she cannot share his interests. For young children, gender looms large.

transgender an umbrella term describing people whose gender identity or expression differs from that associated with their birth sex.

For a transgender person, comparing one’s personal gender identity with cultural concepts of gender roles produces feelings of confusion and discord. A transgender person’s gender identity differs from the behaviors or traits considered typical for that person’s birth sex (APA, 2010; Bockting, 2014). A person who was born a female may feel he is a man living in a woman’s body, or a person born male may feel she is a woman living in a man’s body. Some transgender people are also transsexual: They prefer to live as members of the other birth sex. Some transsexual people (about three times as many men as women) may seek medical treatment (including sex-reassignment surgery) to achieve their preferred gender identity (Van Kesteren et al., 1997).

170

“The more I was treated as a woman, the more woman I became.”

Writer Jan Morris, male-to-female transsexual

Note that gender identity is distinct from sexual orientation (the direction of one’s sexual attraction). Transgender people may be sexually attracted to people of the opposite birth sex (heterosexual), the same birth sex (homosexual), both sexes (bisexual), or to no one at all (asexual).

Transgender people may express their gender identity by dressing as a person of the other biological sex typically would. Most who dress this way are biological males who are attracted to women (APA, 2010).

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

What are gender roles, and what do their variations tell us about our human capacity for learning and adaptation?

Gender roles are social rules or norms for accepted and expected behavior for females and males. The norms associated with various roles, including gender roles, vary widely in different cultural contexts, which is proof that we are very capable of learning and adapting to the social demands of different environments.

Reflections on Nature, Nurture, and Their Interaction

4-18 What is included in the biopsychosocial approach to development?

“There are trivial truths and great truths,” reflected the physicist Niels Bohr on the paradoxes of science. “The opposite of a trivial truth is plainly false. The opposite of a great truth is also true.” Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm predisposed both our shared humanity and our individual differences. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

171

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference through norms that shower benefits on macho men and gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. Roles remake their players. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength is becoming increasingly less important for power and status (think Mark Zuckerberg and Hillary Clinton). From 1960 into the next century, women soared from 6 percent to nearly 50 percent of U.S. medical school graduates (AAMC, 2012). In the mid-1960s, U.S. married women devoted seven times as many hours to housework as did their husbands; by 2003 this gap had shrunk to twice as many (Bianchi et al., 2000, 2006). Such swift changes signal that biology does not fix gender roles.

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

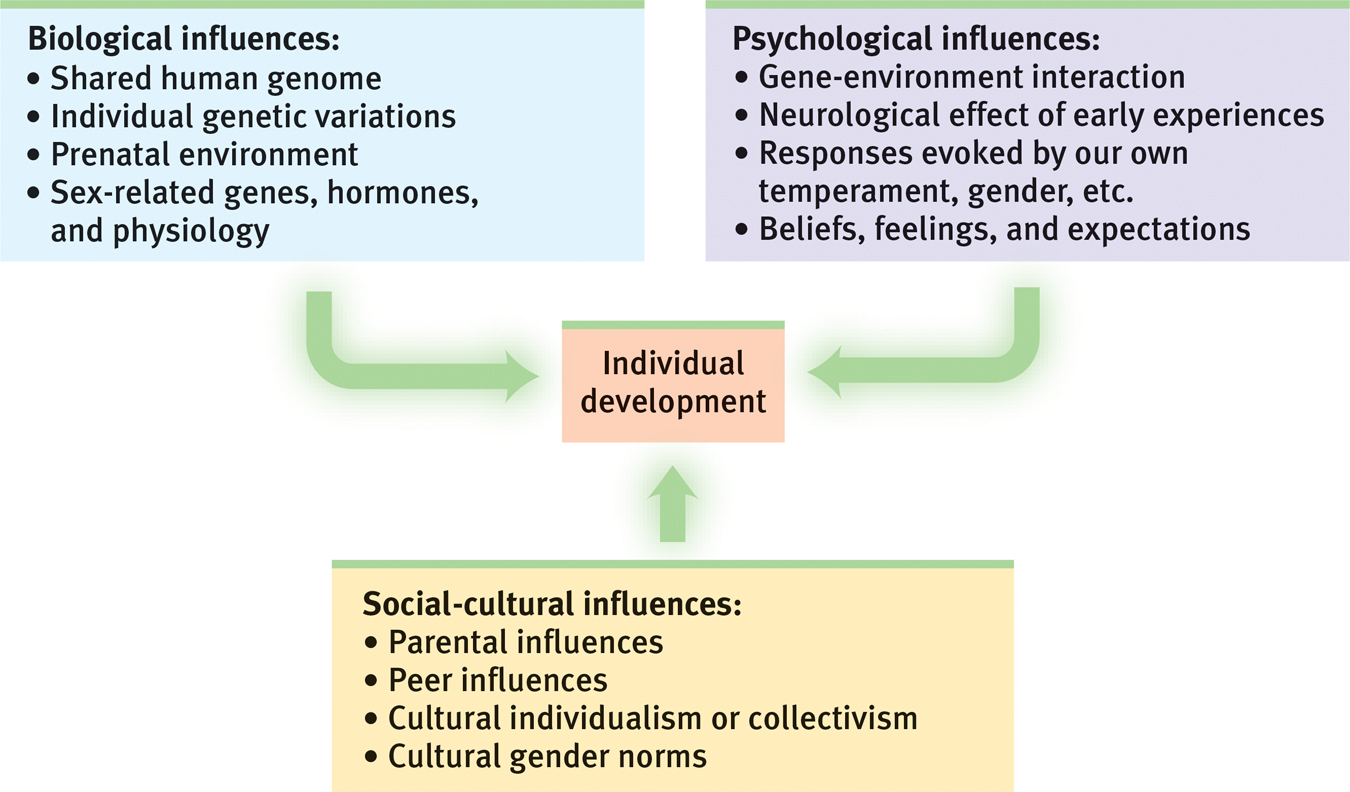

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we are also an open system (FIGURE 4.10 below). Genes are all-pervasive but not all-powerful. People may reject their evolutionary role as transmitters of genes and choose not to reproduce. Culture, too, is all-pervasive but not all-powerful. People may defy peer pressures and do the opposite of the expected.

Figure 4.10

Figure 4.10The biopsychosocial approach to development

We can’t excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both the creatures and the creators of our worlds. So many things about us—including our gender identities and our mating behaviors—are the products of our genes and environments. Yet the future-shaping stream of causation runs through our present choices. Our decisions today design our environments tomorrow. The human environment is not like the weather—something that just happens randomly. We are its architects. Our hopes, goals, and expectations influence our future. And that is what enables cultures to vary and to change. Mind matters.

172

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

How does the biopsychosocial approach explain our individual development?

The biopsychosocial approach considers all the factors that influence our individual development: biological factors (including evolution and our genes, hormones, and brain), psychological factors (including our experiences, beliefs, feelings, and expectations), and social-cultural factors (including parental and peer influences, cultural individualism or collectivism, and gender norms).

***

“Let’s hope that it’s not true; but if it is true, let’s hope that it doesn’t become widely known.”

Lady Ashley, commenting on Darwin’s theory

We know from our correspondence and from surveys that some readers feel troubled by the naturalism and evolutionism of contemporary science. (Readers from other nations bear with us, but in the United States there is a wide gulf between scientific and lay thinking about evolution.) “The idea that human minds are the product of evolution is … unassailable fact,” declared a 2007 editorial in Nature, a leading science journal. That sentiment concurs with a 2006 statement of “evidence-based facts” about evolution jointly issued by the national science academies of 66 nations (IAP, 2006). In The Language of God, Human Genome Project director Francis Collins (2006, pp. 141, 146), a self-described evangelical Christian, compiled the “utterly compelling” evidence that led him to conclude that Darwin’s big idea is “unquestionably correct.” Yet Gallup pollsters have reported that half of U.S. adults do not believe in evolution’s role in “how human beings came to exist on Earth” (Newport, 2007). Many of those who dispute the scientific story worry that a science of behavior (and evolutionary science in particular) will destroy our sense of the beauty, mystery, and spiritual significance of the human creature. For those concerned, we offer some reassuring thoughts.

When Isaac Newton explained the rainbow in terms of light of differing wavelengths, the British poet John Keats feared that Newton had destroyed the rainbow’s mysterious beauty. Yet, as Richard Dawkins (1998) noted in Unweaving the Rainbow, Newton’s analysis led to an even deeper mystery—Einstein’s theory of special relativity. Moreover, nothing about Newton’s optics need diminish our appreciation for the dramatic elegance of a rainbow arching across a brightening sky.

“Is it not stirring to understand how the world actually works—that white light is made of colors, that color measures light waves, that transparent air reflects light … ? It does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little about it.”

Carl Sagan, Skies of Other Worlds, 1988

When Galileo assembled evidence that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa, he did not offer irrefutable proof for his theory. Rather, he offered a coherent explanation for a variety of observations, such as the changing shadows cast by the Moon’s mountains. His explanation eventually won the day because it described and explained things in a way that made sense, that hung together. Darwin’s theory of evolution likewise is a coherent view of natural history. It offers an organizing principle that unifies various observations.

173

Collins is not the only person of faith to find the scientific idea of human origins congenial with his spirituality. In the fifth century, St. Augustine (quoted by Wilford, 1999) wrote, “The universe was brought into being in a less than fully formed state, but was gifted with the capacity to transform itself from unformed matter into a truly marvelous array of structures and life forms.” Some 1600 years later, Pope John Paul II in 1996 welcomed a science-religion dialogue, finding it noteworthy that evolutionary theory “has been progressively accepted by researchers, following a series of discoveries in various fields of knowledge.”

Meanwhile, many people of science are awestruck at the emerging understanding of the universe and the human creature. It boggles the mind—the entire universe popping out of a point some 14 billion years ago, and instantly inflating to cosmological size. Had the energy of this Big Bang been the tiniest bit less, the universe would have collapsed back on itself. Had it been the tiniest bit more, the result would have been a soup too thin to support life. Astronomer Sir Martin Rees has described Just Six Numbers (1999), any one of which, if changed ever so slightly, would produce a cosmos in which life could not exist. Had gravity been a tad stronger or weaker, or had the weight of a carbon proton been a wee bit different, our universe just wouldn’t have worked.

What caused this almost-too-good-to-be-true, finely tuned universe? Why is there something rather than nothing? How did it come to be, in the words of Harvard-Smithsonian astrophysicist Owen Gingerich (1999), “so extraordinarily right, that it seemed the universe had been expressly designed to produce intelligent, sentient beings”? Is there a benevolent superintelligence behind it all? Have there instead been an infinite number of universes born and we just happen to be the lucky inhabitants of one that, by chance, was exquisitely fine-tuned to give birth to us? Or does that idea violate Occam’s razor, the principle that we should prefer the simplest of competing explanations? On such matters, a humble, awed, scientific silence is appropriate, suggested philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent” (1922, p. 189).

“The causes of life’s history [cannot] resolve the riddle of life’s meaning.”

Stephen Jay Gould, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, 1999

Rather than fearing science, we can welcome its enlarging our understanding and awakening our sense of awe. In The Fragile Species, Lewis Thomas (1992) described his utter amazement that the Earth in time gave rise to bacteria and eventually to Bach’s Mass in B Minor. In a short 4 billion years, life on Earth has come from nothing to structures as complex as a 6-billion-unit strand of DNA and the incomprehensible intricacy of the human brain. Atoms no different from those in a rock somehow formed dynamic entities that became conscious. Nature, said cosmologist Paul Davies (2007), seems cunningly and ingeniously devised to produce extraordinary, self-replicating, information-processing systems—us. Although we appear to have been created from dust, over eons of time, the end result is a priceless creature, one rich with potential beyond our imagining.

174

REVIEW: Culture, Gender, and Other Environmental Influences

|

REVIEW | Culture, Gender, and Other Environmental Influences |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

4-10 How do early experiences modify the brain?

Our genetic predispositions and our specific environments interact. Environments can trigger gene activity, and genetically influenced traits can evoke responses from others.

As a child’s brain develops, neural connections grow more numerous and complex. Experiences then prompt a pruning process, in which unused connections weaken and heavily used ones strengthen. Early childhood is an important period for shaping the brain, but throughout our lives our brain modifies itself in response to our learning.

4-11 In what ways do parents and peers shape children’s development?

Parents influence their children in areas such as manners and political and religious beliefs, but not in other areas, such as personality. As children attempt to fit in with their peers, they tend to adopt their culture—styles, accents, slang, attitudes. By choosing their children’s neighborhoods and schools, parents exert some influence over peer group culture.

4-12 How does culture affect our behavior?

A culture is an enduring set of behaviors, ideas, attitudes, values, and traditions shared by a group and transmitted from one generation to the next. Cultural norms are understood rules that inform members of a culture about accepted and expected behaviors. Cultures differ across time and space.

4-13 How do individualist and collectivist cultures differ in their values and goals?

Within any culture, the degree of individualism or collectivism varies from person to person. Cultures based on self-reliant individualism, like those found in North America and Western Europe, tend to value personal independence and individual achievement. They define identity in terms of self-esteem, personal goals and attributes, and personal rights and liberties. Cultures based on socially connected collectivism, like those in many parts of Asia and Africa, tend to value interdependence, tradition, and harmony, and they define identity in terms of group goals, commitments, and belonging to one’s group.

4-14 How does the meaning of gender differ from the meaning of sex?

In psychology, gender is the socially influenced characteristics by which people define men and women. Sex refers to the biologically influenced characteristics by which people define males and females. Our gender is thus the product of the interplay among our biological dispositions, our developmental experiences, and our current situation.

4-15 What are some ways in which males and females tend to be alike and to differ?