9.1 Thinking

Please continue to the next section.

Concepts

cognition all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating.

9-

concept a mental grouping of similar objects, events, ideas, or people.

prototype a mental image or best example of a category. Matching new items to a prototype provides a quick and easy method for sorting items into categories (as when comparing feathered creatures to a prototypical bird, such as a robin).

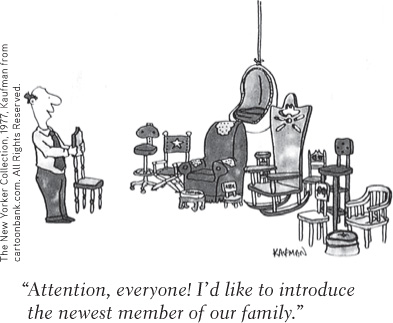

Psychologists who study cognition FOCUS on the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating information. One of these activities is forming concepts—mental groupings of similar objects, events, ideas, or people. The concept chair includes many items—

We often form our concepts by developing prototypes—a mental image or best example of a category (Rosch, 1978). People more quickly agree that “a robin is a bird” than that “a penguin is a bird.” For most of us, the robin is the birdier bird; it more closely resembles our bird prototype. Similarly, for people in modern multiethnic Germany, Caucasian Germans are more prototypically German (Kessler et al., 2010). And the more closely something matches our prototype of a concept—

Figure 9.1

Figure 9.1Tasty fungus? Botanically, a mushroom is a fungus. But it doesn’t fit most people’s fungus prototype.

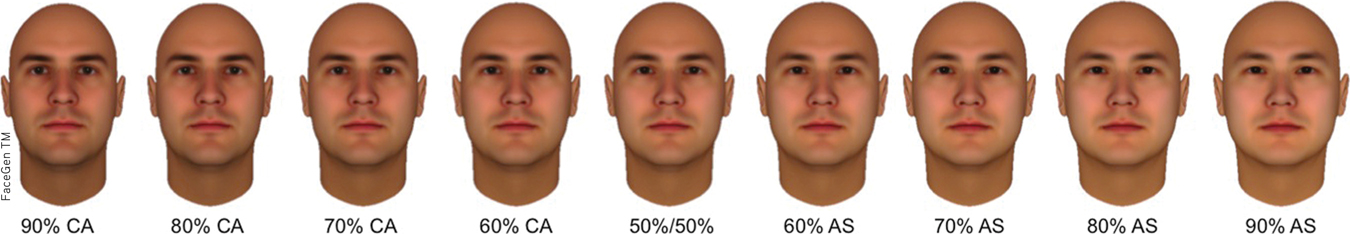

Once we place an item in a category, our memory of it later shifts toward the category prototype, as it did for Belgian students who viewed ethnically blended faces. For example, when viewing a blended face in which 70 percent of the features were Caucasian and 30 percent were Asian, the students categorized the face as Caucasian (FIGURE 9.2). Later, as their memory shifted toward the Caucasian prototype, they were more likely to remember an 80 percent Caucasian face than the 70 percent Caucasian they had actually seen (Corneille et al., 2004). Likewise, if shown a 70 percent Asian face, they later remembered a more prototypically Asian face. So, too, with gender: People who viewed 70 percent male faces categorized them as male (no surprise there) and then later misremembered them as even more prototypically male (Huart et al., 2005).

Figure 9.2

Figure 9.2Categorizing faces influences recollection Shown a face that was 70 percent Caucasian, people tended to classify the person as Caucasian and to recollect the face as more Caucasian than it was. (Recreation of experiment courtesy of Olivier Corneille.)

Move away from our prototypes, and category boundaries may blur. Is a tomato a fruit? Is a 17-

357

Problem Solving: Strategies and Obstacles

9-

algorithm a methodical, logical rule or procedure that guarantees solving a particular problem. Contrasts with the usually speedier—but also more error-prone—use of heuristics.

One tribute to our rationality is our problem-

heuristic a simple thinking strategy that often allows us to make judgments and solve problems efficiently; usually speedier but also more error-prone than algorithms.

Some problems we solve through trial and error. Thomas Edison tried thousands of light bulb filaments before stumbling upon one that worked. For other problems, we use algorithms, step-

insight a sudden realization of a problem’s solution; contrasts with strategy-based solutions.

Sometimes we puzzle over a problem and the pieces suddenly fall together in a flash of insight—an abrupt, true-

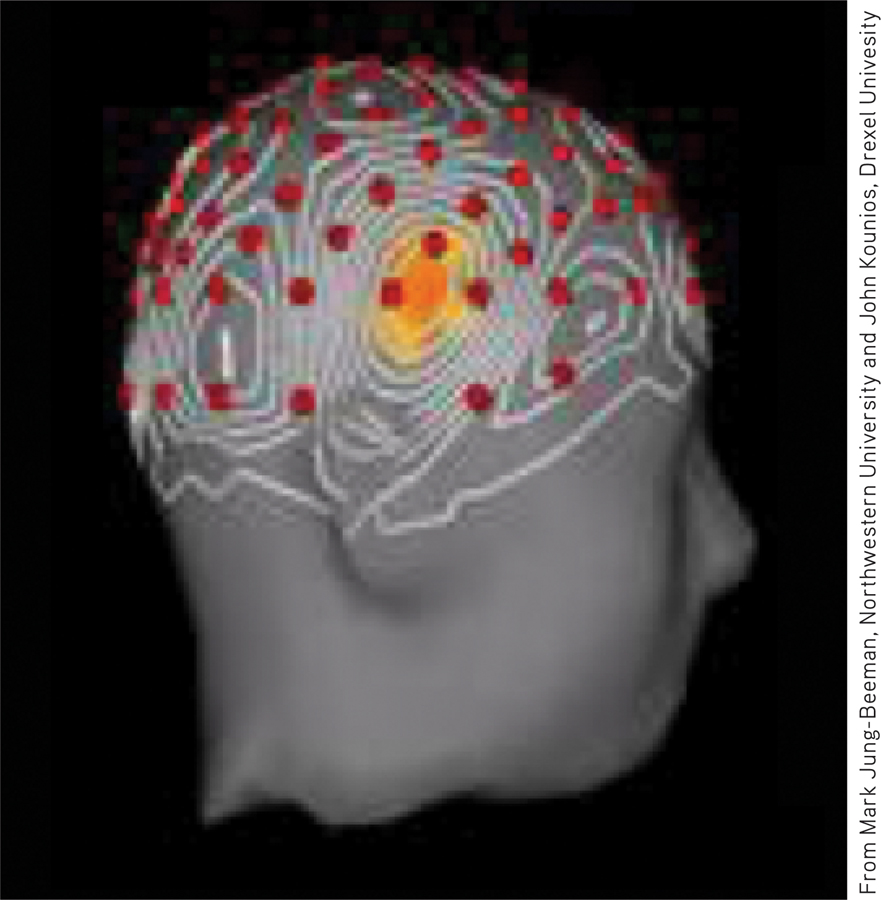

Teams of researchers have identified brain activity associated with sudden flashes of insight (Kounios & Beeman, 2009; Sandkühler & Bhattacharya, 2008). They gave people a problem: Think of a word that will form a compound word or phrase with each of three other words in a set (such as pine, crab, and sauce), and press a button to sound a bell when you know the answer. (If you need a hint: The word is a fruit.2) EEGs or fMRIs (functional MRIs) revealed the problem solver’s brain activity. In the first experiment, about half the solutions were by a sudden Aha! insight. Before the Aha! moment, the problem solvers’ frontal lobes (which are involved in focusing attention) were active, and there was a burst of activity in the right temporal lobe, just above the ear (FIGURE 9.3 below). In another experiment, researchers used electrical stimulation to decrease left hemisphere activity and increase right hemisphere activity. The result was improved insight, less restrained by the assumptions created by past experience (Chi & Snyder, 2011).

Figure 9.3

Figure 9.3The Aha! moment A burst of right temporal lobe activity accompanied insight solutions to word problems (Jung-

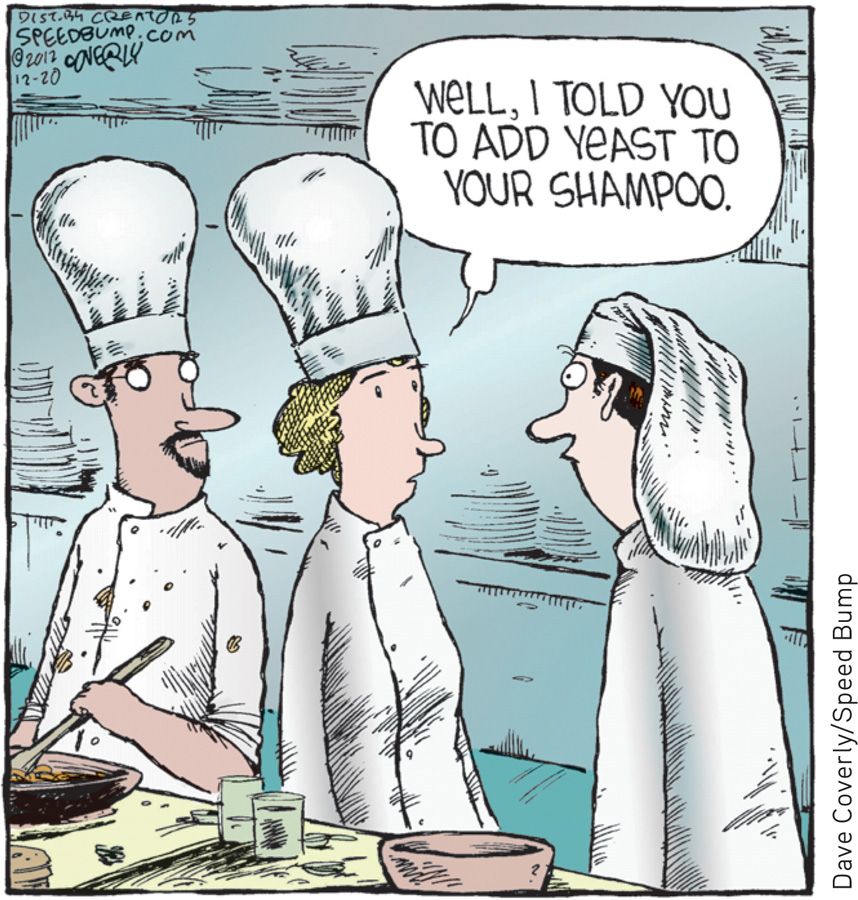

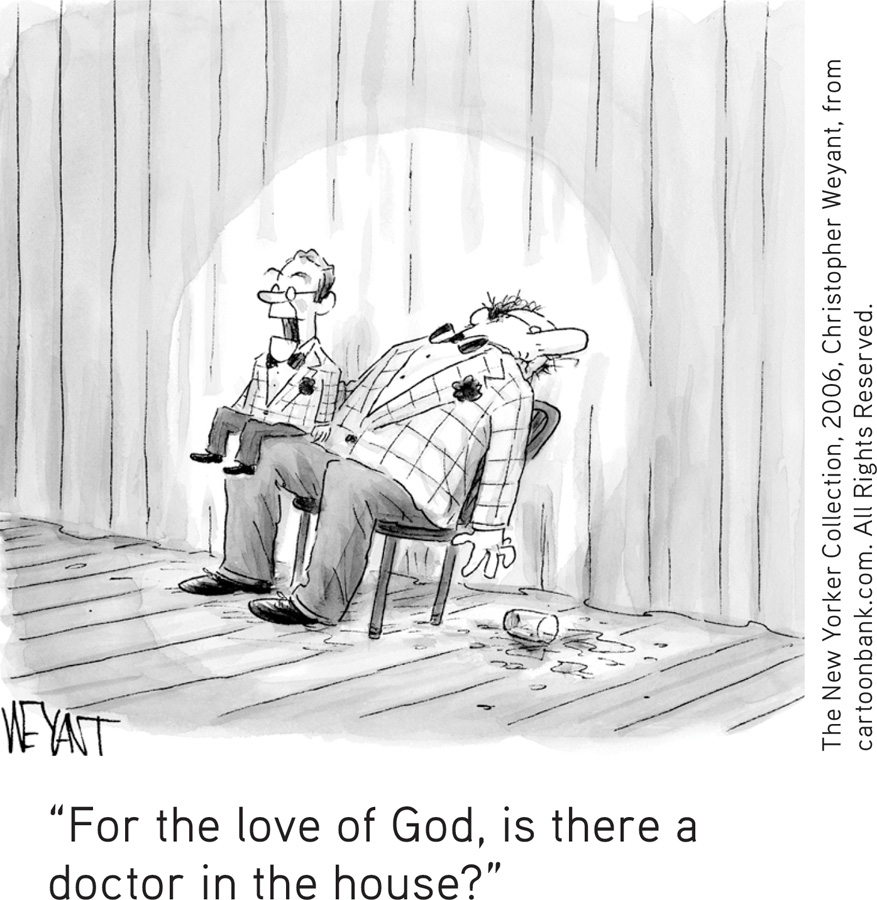

Insight strikes suddenly, with no prior sense of “getting warmer” or feeling close to a solution (Knoblich & Oellinger, 2006; Metcalfe, 1986). When the answer pops into mind (apple!), we feel a happy sense of satisfaction. The joy of a joke may similarly lie in our sudden comprehension of an unexpected ending or a double meaning: “You don’t need a parachute to skydive. You only need a parachute to skydive twice.” Comedian Groucho Marx was a master at this: “I once shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I’ll never know.”

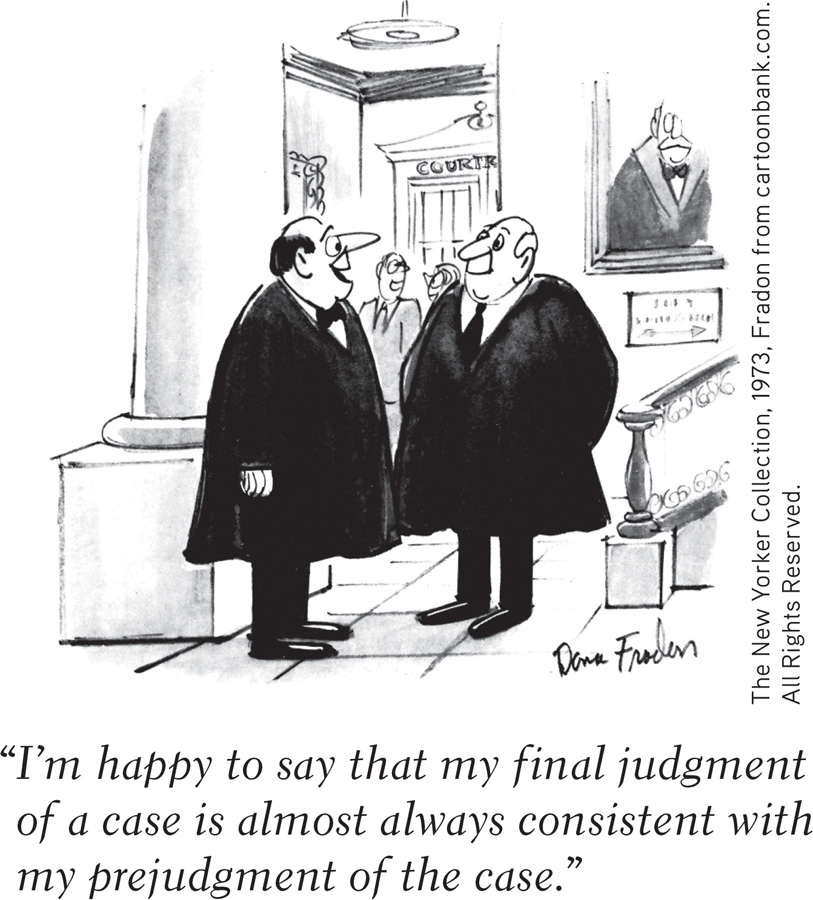

confirmation bias a tendency to search for information that supports our preconceptions and to ignore or distort contradictory evidence.

Inventive as we are, other cognitive tendencies may lead us astray. For example, we more eagerly seek out and favor evidence that supports our ideas than evidence that refutes them (Klayman & Ha, 1987; Skov & Sherman, 1986). Peter Wason (1960) demonstrated this tendency, known as confirmation bias, by giving British university students the three-

358

“Ordinary people,” said Wason (1981), “evade facts, become inconsistent, or systematically defend themselves against the threat of new information relevant to the issue.” Thus, once people form a belief—

“The human understanding, when any proposition has been once laid down … forces everything else to add fresh support and confirmation.”

Francis Bacon, Novum Organum, 1620

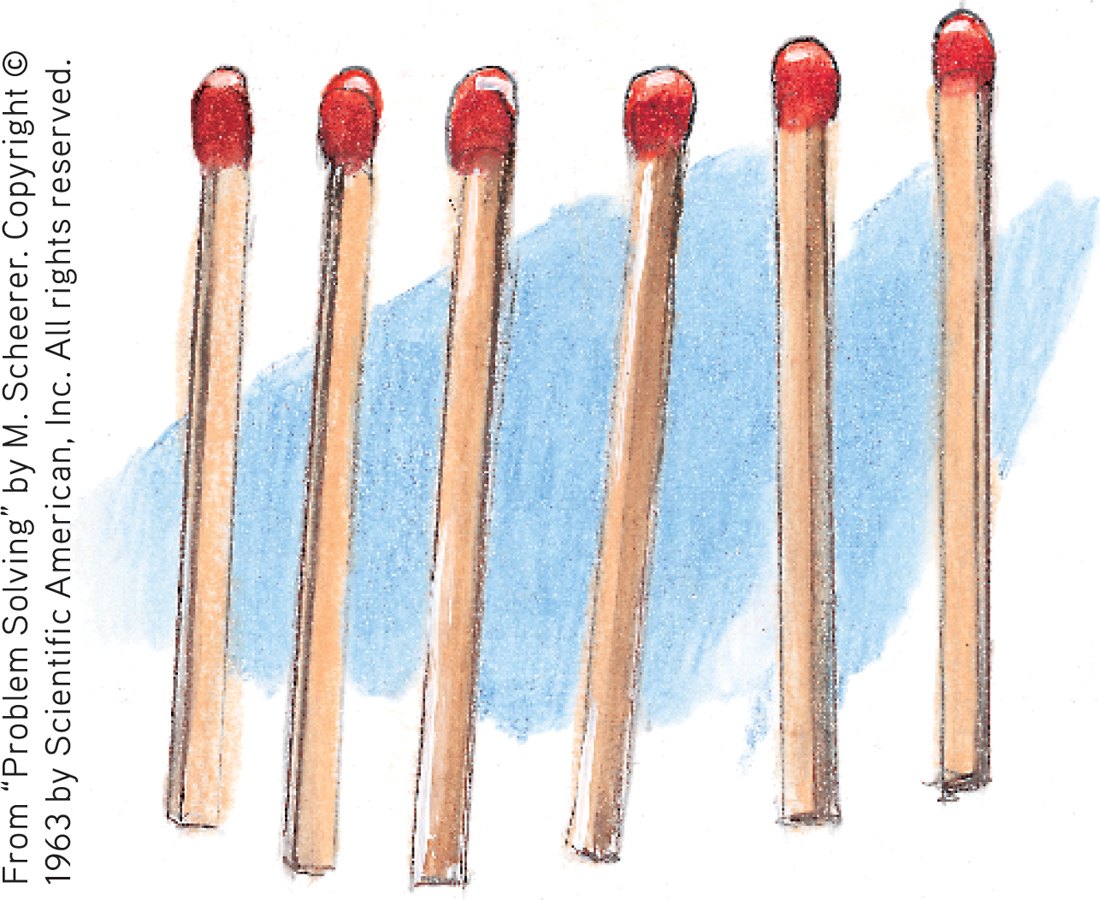

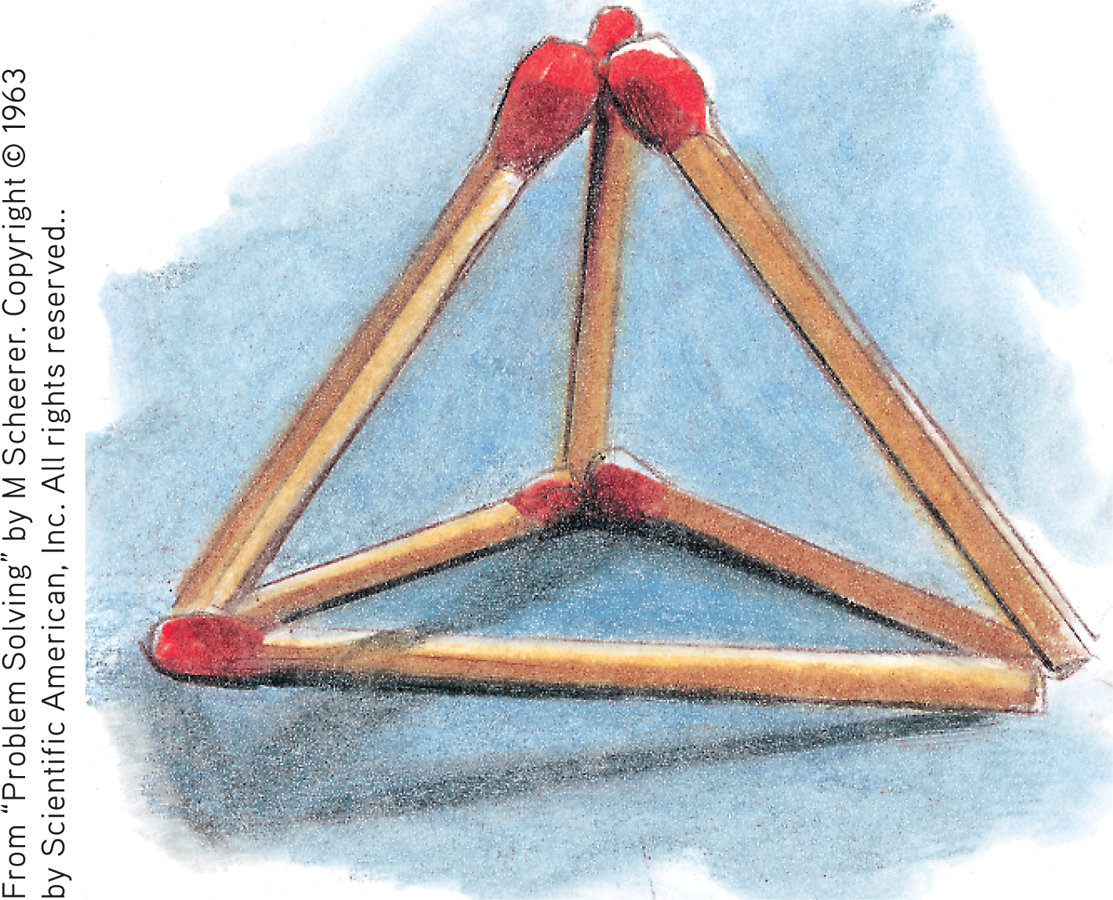

Once we incorrectly represent a problem, it’s hard to restructure how we approach it. If the solution to the matchstick problem in FIGURE 9.4 eludes you, you may be experiencing fixation—an inability to see a problem from a fresh perspective. (For the solution, see FIGURE 9.5.)

Figure 9.4

Figure 9.4The matchstick problem How would you arrange six matches to form four equilateral triangles?

Figure 9.5

Figure 9.5Solution to the matchstick problem To solve this problem, you must view it from a new perspective, breaking the fixation of limiting solutions to two dimensions.

mental set a tendency to approach a problem in one particular way, often a way that has been successful in the past.

A prime example of fixation is mental set, our tendency to approach a problem with the mind-

Given the sequence O-

Most people have difficulty recognizing that the three final letters are F(ive), S(ix), and S(even). But solving this problem may make the next one easier:

Given the sequence J-

As a perceptual set predisposes what we perceive, a mental set predisposes how we think; sometimes this can be an obstacle to problem solving, as when our mental set from our past experiences with matchsticks predisposes us to arrange them in two dimensions.

359

Forming Good and Bad Decisions and Judgments

intuition an effortless, immediate, automatic feeling or thought, as contrasted with explicit, conscious reasoning.

9-

When making each day’s hundreds of judgments and decisions (Is it worth the bother to take a jacket? Can I trust this person? Should I shoot the basketball or pass to the player who’s hot?), we seldom take the time and effort to reason systematically. We just follow our intuition, our fast, automatic, unreasoned feelings and thoughts. After interviewing policy makers in government, business, and education, social psychologist Irving Janis (1986) concluded that they “often do not use a reflective problem-

availability heuristic estimating the likelihood of events based on their availability in memory; if instances come readily to mind (perhaps because of their vividness), we presume such events are common.

The Availability Heuristic

When we need to act quickly, the mental shortcuts we call heuristics enable snap judgments. Thanks to our mind’s automatic information processing, intuitive judgments are instantaneous. They also are usually effective (Gigerenzer & Sturm, 2012). However, research by cognitive psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman (1974) showed how these generally helpful shortcuts can lead even the smartest people into dumb decisions.3 The availability heuristic operates when we estimate the likelihood of events based on how mentally available they are—

“Kahneman and his colleagues and students have changed the way we think about the way people think.”

American Psychological Association President Sharon Brehm, 2007

The availability heuristic can distort our judgments of other people, too. Anything that makes information pop into mind—

“In creating these problems, we didn’t set out to fool people. All our problems fooled us, too.” Amos Tversky (1985)

|

“Intuitive thinking [is] fine most of the time…. But sometimes that habit of mind gets us in trouble.” Daniel Kahneman (2005)

|

360

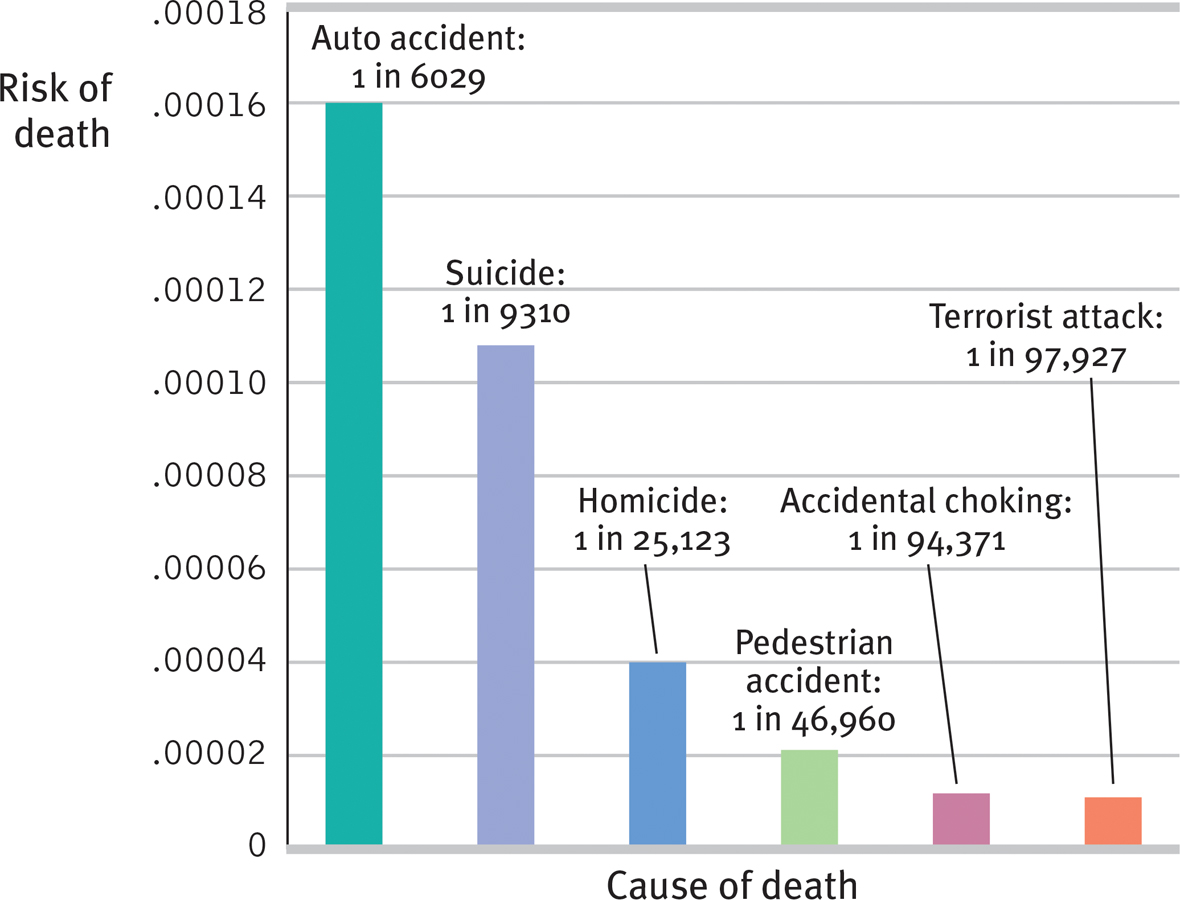

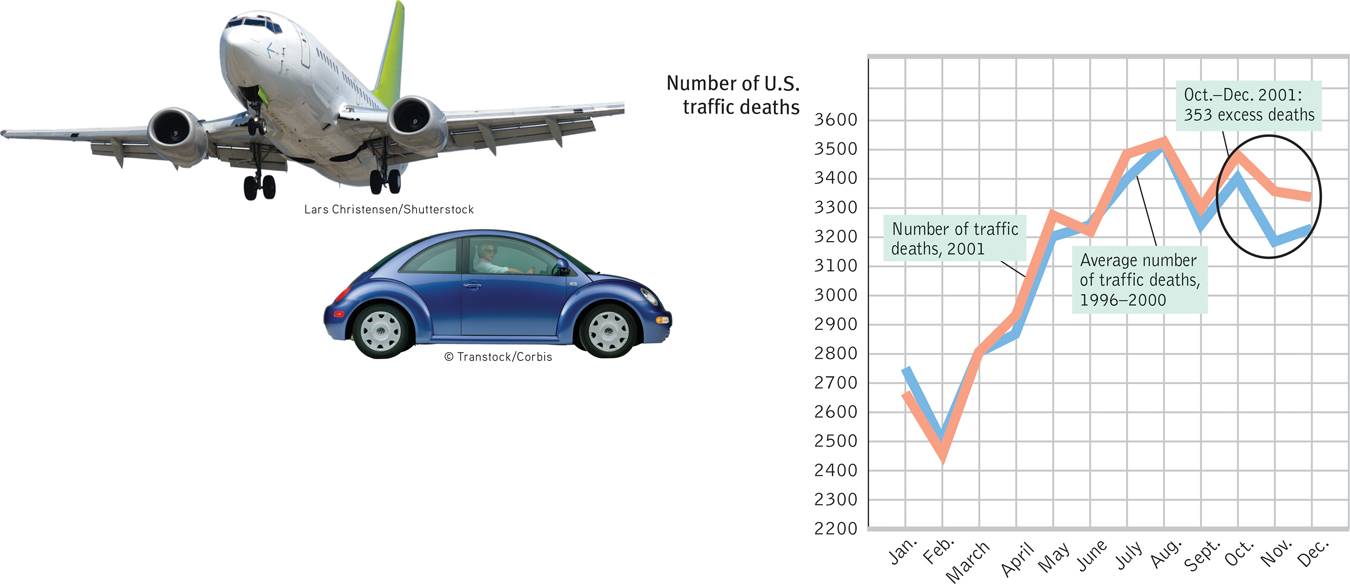

Even during that horrific year, terrorist acts claimed comparatively few lives. Yet when the statistical reality of greater dangers (see FIGURE 9.6) was pitted against the 9/11 terror, the memorable case won: Emotion-

Figure 9.6

Figure 9.6Risk of death from various causes in the United States, 2001 (Data assembled from various government sources by Randall Marshall et al., 2007.)

“Don’t believe everything you think.”

Bumper sticker

We often fear the wrong things (See below for Thinking Critically About: The Fear Factor). We fear flying because we visualize air disasters. We fear letting our sons and daughters walk to school because we see mental snapshots of abducted and brutalized children. We fear swimming in ocean waters because we replay Jaws with ourselves as victims. Even just passing by a person who sneezes and coughs heightens our perceptions of various health risks (Lee et al., 2010). And so, thanks to such readily available images, we come to fear extremely rare events.

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Fear Factor—Why We Fear the Wrong Things

9-4 What factors contribute to our fear of unlikely events?

After the 9/11 attacks, many people feared flying more than driving. In a 2006 Gallup survey, only 40 percent of Americans reported being “not afraid at all” to fly. Yet from 2009 to 2011 Americans were—mile for mile—170 times more likely to die in a vehicle accident than on a scheduled flight (National Safety Council, 2014). In 2011, 21,221 people died in U.S. car or light truck accidents, while zero (as in 2010) died on scheduled airline flights. When flying, the most dangerous part of the trip is the drive to the airport.

In a late 2001 essay, I [DM] calculated that if—because of 9/11—we flew 20 percent less and instead drove half those unflown miles, about 800 more people would die in the year after the 9/11 attacks (Myers, 2001). German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer (2004, 2006; Gaissmaier & Gigerenzer, 2012) later checked my estimate against actual accident data. (Why didn’t I think to do that?) U.S. traffic deaths did indeed increase significantly in the last three months of 2001 (FIGURE 9.7). By the end of 2002, Gigerenzer estimated, 1600 Americans had “lost their lives on the road by trying to avoid the risk of flying.”

Figure 9.7

Figure 9.7Scared onto deadly highways Images of 9/11 etched a sharper image in American minds than did the millions of fatality-

Why do we in so many ways fear the wrong things? Why do so many American parents fear school shootings, when their child is more likely to be killed by lightning (Ripley, 2013)? Psychologists have identified four influences that feed fear and cause us to ignore higher risks.

- We fear what our ancestral history has prepared us to fear. Human emotions were road tested in the Stone Age. Our old brain prepares us to fear yesterday’s risks: snakes, lizards, and spiders (which combined now kill a tiny fraction of the number killed by modern-day threats, such as cars and cigarettes). Yesterday’s risks also prepare us to fear confinement and heights, and therefore flying.

- We fear what we cannot control. Driving we control; flying we do not.

- We fear what is immediate. The dangers of flying are mostly telescoped into the moments of takeoff and landing. The dangers of driving are diffused across many moments to come, each trivially dangerous.

- Thanks to the availability heuristic, we fear what is most readily available in memory. Vivid images, like that of United Flight 175 slicing into the World Trade Center, feed our judgments of risk. Thousands of safe car trips have extinguished our anxieties about driving. Shark attacks kill about one American per year, while heart disease kills 800,000—but it’s much easier to visualize a shark bite, and thus many people fear sharks more than cigarettes (Daley, 2011). Similarly, we remember (and fear) widespread disasters (hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes) that kill people dramatically, in bunches. But we fear too little the less dramatic threats that claim lives quietly, one by one, continuing into the distant future. Horrified citizens and commentators renewed calls for U.S. gun control in 2012, after 20 children and 6 adults were slain in a Connecticut elementary school—although even more Americans are murdered by guns daily, though less dramatically, one by one. Philanthropist Bill Gates has noted that each year a half-million children worldwide die from rotavirus. This is the equivalent of four 747s full of children dying every day, and we hear nothing of it (Glass, 2004).

The news, and our own memorable experiences, can make us disproportionately fearful of infinitesimal risks. As one risk analyst explained, “If it’s in the news, don’t worry about it. The very definition of news is ‘something that hardly ever happens’” (Schneier, 2007).

“Fearful people are more dependent, more easily manipulated and controlled, more susceptible to deceptively simple, strong, tough measures and hard-

Media researcher George Gerbner to U.S. Congressional Subcommittee on Communications, 1981

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Why can news be described as “something that hardly ever happens”? How does knowing this help us assess our fears?

If a tragic event such as a plane crash makes the news, it is noteworthy and unusual, unlike much more common bad events, such as traffic accidents. Knowing this, we can worry less about unlikely events and think more about improving the safety of our everyday activities. (For example, we can wear a seat belt when in a vehicle and use the crosswalk when walking.)

To offer a vivid depiction of climate change, Cal Tech scientists created an interactive map of global temperatures over the past 120 years (see www.tinyurl.com/

Meanwhile, the lack of comparably available images of global climate change—

Dramatic outcomes make us gasp; probabilities we hardly grasp. As of 2013, some 40 nations—

overconfidence the tendency to be more confident than correct—to overestimate the accuracy of our beliefs and judgments.

Overconfidence

361

Sometimes our judgments and decisions go awry simply because we are more confident than correct. Across various tasks, people overestimate their performance (Metcalfe, 1998). If 60 percent of people correctly answer a factual question, such as “Is absinthe a liqueur or a precious stone?,” they will typically average 75 percent confidence (Fischhoff et al., 1977). (It’s a licorice-

It was an overconfident BP that, before its exploded drilling platform spewed oil into the Gulf of Mexico, downplayed safety concerns, and then downplayed the spill’s magnitude (Mohr et al., 2010; Urbina, 2010). It is overconfidence that drives stockbrokers and investment managers to market their ability to outperform stock market averages (Malkiel, 2012). A purchase of stock X, recommended by a broker who judges this to be the time to buy, is usually balanced by a sale made by someone who judges this to be the time to sell. Despite their confidence, buyer and seller cannot both be right.

Overconfidence can also feed extreme political views. People with a superficial understanding of proposals for cap-

Hofstadter’s Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law.

Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach: The Eternal Golden Braid, 1979

Classrooms are full of overconfident students who expect to finish assignments and write papers ahead of schedule (Buehler et al., 1994, 2002). In fact, the projects generally take about twice the number of days predicted. We also overestimate our future leisure time (Zauberman & Lynch, 2005). Anticipating how much more we will accomplish next month, we happily accept invitations and assignments, only to discover we’re just as busy when the day rolls around. The same “planning fallacy” (underestimating time and money) appears everywhere. Boston’s mega-

“When you know a thing, to hold that you know it; and when you do not know a thing, to allow that you do not know it; this is knowledge.”

Confucius (551–479 b.c.e.), Analects

Overconfidence can have adaptive value. People who err on the side of overconfidence live more happily. They seem more competent than others (Anderson et al., 2012). Moreover, given prompt and clear feedback, as weather forecasters receive after each day’s predictions, we can learn to be more realistic about the accuracy of our judgments (Fischhoff, 1982). The wisdom to know when we know a thing and when we do not is born of experience.

belief perseverance clinging to one’s initial conceptions after the basis on which they were formed has been discredited.

Belief Perseverance

Our overconfidence is startling; equally so is our belief perseverance—our tendency to cling to our beliefs in the face of contrary evidence. One study of belief perseverence engaged people with opposing views of capital punishment (Lord et al., 1979). After studying two supposedly new research findings, one supporting and the other refuting the claim that the death penalty deters crime, each side was more impressed by the study supporting its own beliefs. And each readily disputed the other study. Thus, showing the pro-

To rein in belief perseverance, a simple remedy exists: Consider the opposite. When the same researchers repeated the capital-

The more we come to appreciate why our beliefs might be true, the more tightly we cling to them. Once we have explained to ourselves why we believe a child is “gifted” or has a “specific learning disorder,” we tend to ignore evidence undermining our belief. Once beliefs form and get justified, it takes more compelling evidence to change them than it did to create them. Prejudice persists. Beliefs often persevere.

362

framing the way an issue is posed; how an issue is framed can significantly affect decisions and judgments.

The Effects of Framing

Framing—the way we present an issue—

Similarly, 9 in 10 college students rated a condom as effective if told it had a supposed “95 percent success rate” in stopping the HIV virus. Only 4 in 10 judged it effective when told it had a “5 percent failure rate” (Linville et al., 1992). To scare people even more, frame risks as numbers, not percentages. People told that a chemical exposure was projected to kill 10 of every 10 million people (imagine 10 dead people!) felt more frightened than did those told the fatality risk was an infinitesimal .000001 (Kraus et al., 1992).

363

Framing can be a powerful persuasion tool. Carefully posed options can nudge people toward decisions that could benefit them or society as a whole (Benartzi & Thaler, 2013; Thaler & Sunstein, 2008):

- Why choosing to be an organ donor depends on where you live. In many European countries as well as the United States, those renewing their driver’s license can decide whether they want to be organ donors. In some countries, the default option is Yes, but people can opt out. Nearly 100 percent of the people in opt-out countries have agreed to be donors. In the United States, Britain, and Germany, the default option is No, but people can “opt in.” There, less than half have agreed to be donors (Hajhosseini et al., 2013; Johnson & Goldstein, 2003).

- How to help employees decide to save for their retirement. A 2006 U.S. pension law recognized the framing effect. Before that law, employees who wanted to contribute to a 401(k) retirement plan typically had to choose a lower take-home pay, which few people will do. Companies can now automatically enroll their employees in the plan but allow them to opt out (which would raise the employees’ take-home pay). In both plans, the decision to contribute is the employee’s. But under the new “opt-out” arrangement, enrollments in one analysis of 3.4 million workers soared from 59 to 86 percent (Rosenberg, 2010).

- How to help save the planet. Although a “carbon tax” may be the most effective way to curb greenhouse gases, many people oppose new taxes. But they are more supportive of funding clean energy development with a “carbon offset” fee (Hardisty et al., 2010).

364

The point to remember: Those who understand the power of framing can use it to nudge our decisions.

The Perils and Powers of Intuition

9-

The perils of intuition—

So, are our heads indeed filled with straw? Good news: Cognitive scientists are also revealing intuition’s powers. Here is a summary of some of the high points:

- Intuition is analysis “frozen into habit” (Simon, 2001). It is implicit knowledge—what we’ve learned and recorded in our brains but can’t fully explain (Chassy & Gobet, 2011; Gore & Sadler-Smith, 2011). Chess masters display this tacit expertise in “blitz chess,” where, after barely more than a glance, they intuitively know the right move (Burns, 2004). We see this expertise in the smart and quick judgments of experienced nurses, firefighters, art critics, car mechanics, and musicians. Skilled athletes can react without thinking. Indeed, conscious thinking may disrupt well-practiced movements such as batting or shooting free throws. For all of us who have developed some special skill, what feels like instant intuition is an acquired ability to perceive and react in an eyeblink.

- Intuition is usually adaptive, enabling quick reactions. Our fast and frugal heuristics let us intuitively assume that fuzzy looking objects are far away—which they usually are, except on foggy mornings. If a stranger looks like someone who previously harmed or threatened us, we may—without consciously recalling the earlier experience—react warily. People’s automatic, unconscious associations with a political position can even predict their future decisions before they consciously make up their minds (Galdi et al., 2008). Newlyweds’ automatic associations—their gut reactions—to their new spouses likewise predict their future marital happiness (McNulty et al., 2013). Our learned associations surface as gut feelings, the intuitions of our two-track mind.

- Intuition is huge. Today’s cognitive science offers many examples of unconscious, automatic influences on our judgments (Custers & Aarts, 2010). Consider: Most people guess that the more complex the choice, the smarter it is to make decisions rationally rather than intuitively (Inbar et al., 2010). Actually, Dutch psychologists have shown that in making complex decisions, we benefit by letting our brain work on a problem without thinking about it (Strick et al., 2010, 2011). In one series of experiments, three groups of people read complex information (about apartments or roommates or art posters or soccer football matches). One group stated their preference immediately after reading information about each of four options. The second group, given several minutes to analyze the information, made slightly smarter decisions. But wisest of all, in study after study, was the third group, whose attention was distracted for a time, enabling their minds to engage in automatic, unconscious processing of the complex information. The practical lesson: Letting a problem “incubate” while we attend to other things can pay dividends (Sio & Ormerod, 2009). Facing a difficult decision involving lots of facts, we’re wise to gather all the information we can, and then say, “Give me some time not to think about this.” By taking time to sleep on it, we let our unconscious mental machinery work. Thanks to our active brain, nonconscious thinking (reasoning, problem solving, decision making, planning) is surprisingly astute (Creswell et al., 2013; Hassin, 2013).

365

Critics of this research remind us that deliberate, conscious thought also furthers smart thinking (Lassiter et al., 2009; Payne et al., 2008). In challenging situations, superior decision makers, including chess players, take time to think (Moxley et al., 2012). And with many sorts of problems, deliberative thinkers are aware of the intuitive option, but know when to override it (Mata et al., 2013). Consider:

A bat and a ball together cost 110 cents.

The bat costs 100 cents more than the ball.

How much does the ball cost?

Most people’s intuitive response—

The bottom line: Our two-

Thinking Creatively

creativity the ability to produce new and valuable ideas.

9-

Creativity is the ability to produce ideas that are both novel and valuable (Hennessey & Amabile, 2010). Consider Princeton mathematician Andrew Wiles’ incredible, creative moment. Pierre de Fermat, a seventeenth-

convergent thinking narrowing the available problem solutions to determine the single best solution.

Wiles had pondered Fermat’s theorem for more than 30 years and had come to the brink of a solution. One morning, out of the blue, the final “incredible revelation” struck him. “It was so indescribably beautiful; it was so simple and so elegant. I couldn’t understand how I’d missed it…. It was the most important moment of my working life” (Singh, 1997, p. 25).

divergent thinking expanding the number of possible problem solutions; creative thinking that diverges in different directions.

Creativity like Wiles’ is supported by a certain level of aptitude (ability to learn). Those who score exceptionally high in quantitative aptitude as 13-

366

Although there is no agreed-

- Expertise—well-developed knowledge—furnishes the ideas, images, and phrases we use as mental building blocks. “Chance favors only the prepared mind,” observed Louis Pasteur. The more blocks we have, the more chances we have to combine them in novel ways. Wiles’ well-developed knowledge put the needed theorems and methods at his disposal.

- Imaginative thinking skills provide the ability to see things in novel ways, to recognize patterns, and to make connections. Having mastered a problem’s basic elements, we redefine or explore it in a new way. Copernicus first developed expertise regarding the solar system and its planets, and then creatively defined the system as revolving around the Sun, not the Earth. Wiles’ imaginative solution combined two partial solutions.

- A venturesome personality seeks new experiences, tolerates ambiguity and risk, and perseveres in overcoming obstacles. Wiles said he labored in near-isolation from the mathematics community partly to stay focused and avoid distraction. Such determination is an enduring trait.

- Intrinsic motivation is being driven more by interest, satisfaction, and challenge than by external pressures (Amabile & Hennessey, 1992). Creative people focus less on extrinsic motivators—meeting deadlines, impressing people, or making money—than on the pleasure and stimulation of the work itself. Asked how he solved such difficult scientific problems, Isaac Newton reportedly answered, “By thinking about them all the time.” Wiles concurred: “I was so obsessed by this problem that … I was thinking about it all the time—[from] when I woke up in the morning to when I went to sleep at night” (Singh & Riber, 1997).

- A creative environment sparks, supports, and refines creative ideas. Wiles stood on the shoulders of others and collaborated with a former student. After studying the careers of 2026 prominent scientists and inventors, Dean Keith Simonton (1992) noted that the most eminent were mentored, challenged, and supported by their colleagues. Creativity-fostering environments support innovation, team building, and communication (Hülsheger et al., 2009). They also minimize anxiety and foster contemplation (Byron & Khazanchi, 2011). After Jonas Salk solved a problem that led to the polio vaccine while in a monastery, he designed the Salk Institute to provide contemplative spaces where scientists could work without interruption (Sternberg, 2006).

For those seeking to boost the creative process, research offers some ideas:

- Develop your expertise. Ask yourself what you care about and most enjoy. Follow your passion and become an expert at something.

- Allow time for incubation. Given sufficient knowledge available for novel connections, a period of inattention to a problem (“sleeping on it”) allows for automatic processing to form associations (Zhong et al., 2008). So think hard on a problem, then set it aside and come back to it later.

- Set aside time for the mind to roam freely. Take time away from attention-absorbing distractions. Creativity springs from “defocused attention” (Simonton, 2012a,b). So jog, go for a long walk, or meditate. Serenity seeds spontaneity.

- Experience other cultures and ways of thinking. Living abroad sets the creative juices flowing. Even after controlling for other variables, students who have spent time abroad and embraced their host culture are more adept at working out creative solutions to problems (Lee et al., 2012; Tadmor et al., 2012). Multicultural experiences expose us to multiple perspectives and facilitate flexible thinking, and may also trigger another stimulus for creativity—a sense of difference from others (Kim et al., 2013; Ritter et al., 2012).

367

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Match the process or strategy listed below (1–10) with its description (a–j).

1. Algorithm

2. Intuition

3. Insight

4. Heuristics

5. Fixation

6. Confirmation bias

7. Overconfidence

8. Creativity

9. Framing

10. Belief perseverance

a. Inability to view problems from a new angle; focuses thinking but hinders creative problem solving.

b. Methodological rule or procedure that guarantees a solution but requires time and effort.

c. Fast, automatic, effortless feelings and thoughts based on our experience; huge and adaptive but can lead us to overfeel and underthink.

d. Simple thinking shortcuts that allow us to act quickly and efficiently, but put us at risk for errors.

e. Sudden Aha! reaction that provides instant realization of the solution.

f. Tendency to search for support for our own views and ignore contradictory evidence.

g. Ignoring evidence that proves our beliefs are wrong; closes our mind to new ideas.

h. Overestimating the accuracy of our beliefs and judgments; allows us to be happy and to make decisions easily, but puts us at risk for errors.

i. Wording a question or statement so that it evokes a desired response; can influence others’ decisions and produce a misleading result.

j. The ability to produce novel and valuable ideas.

1. b, 2. c, 3. e, 4. d, 5. a, 6. f, 7. h, 8. j, 9. i, 10. g

Do Other Species Share Our Cognitive Skills?

9-

Other animals are smarter than we often realize. In her 1908 book, The Animal Mind, pioneering psychologist Margaret Floy Washburn argued that animal consciousness and intelligence can be inferred from their behavior. In 2012, neuroscientists convening at the University of Cambridge added that animal consciousness can also be inferred from their brains: “Nonhuman animals, including all mammals and birds,” possess the neural networks “that generate consciousness” (Low et al., 2012). Consider, then, what animal brains can do.

Using Concepts and Numbers

368

Even pigeons—

Until his death in 2007, Alex, an African Grey parrot, categorized and named objects (Pepperberg, 2009, 2012, 2013). Among his jaw-

Displaying Insight

Psychologist Wolfgang Köhler (1925) showed that we are not the only creatures to display insight. He placed a piece of fruit and a long stick outside the cage of a chimpanzee named Sultan, beyond his reach. Inside the cage, he placed a short stick, which Sultan grabbed, using it to try to reach the fruit. After several failed attempts, he dropped the stick and seemed to survey the situation. Then suddenly (as if thinking “Aha!”), Sultan jumped up and seized the short stick again. This time, he used it to pull in the longer stick—

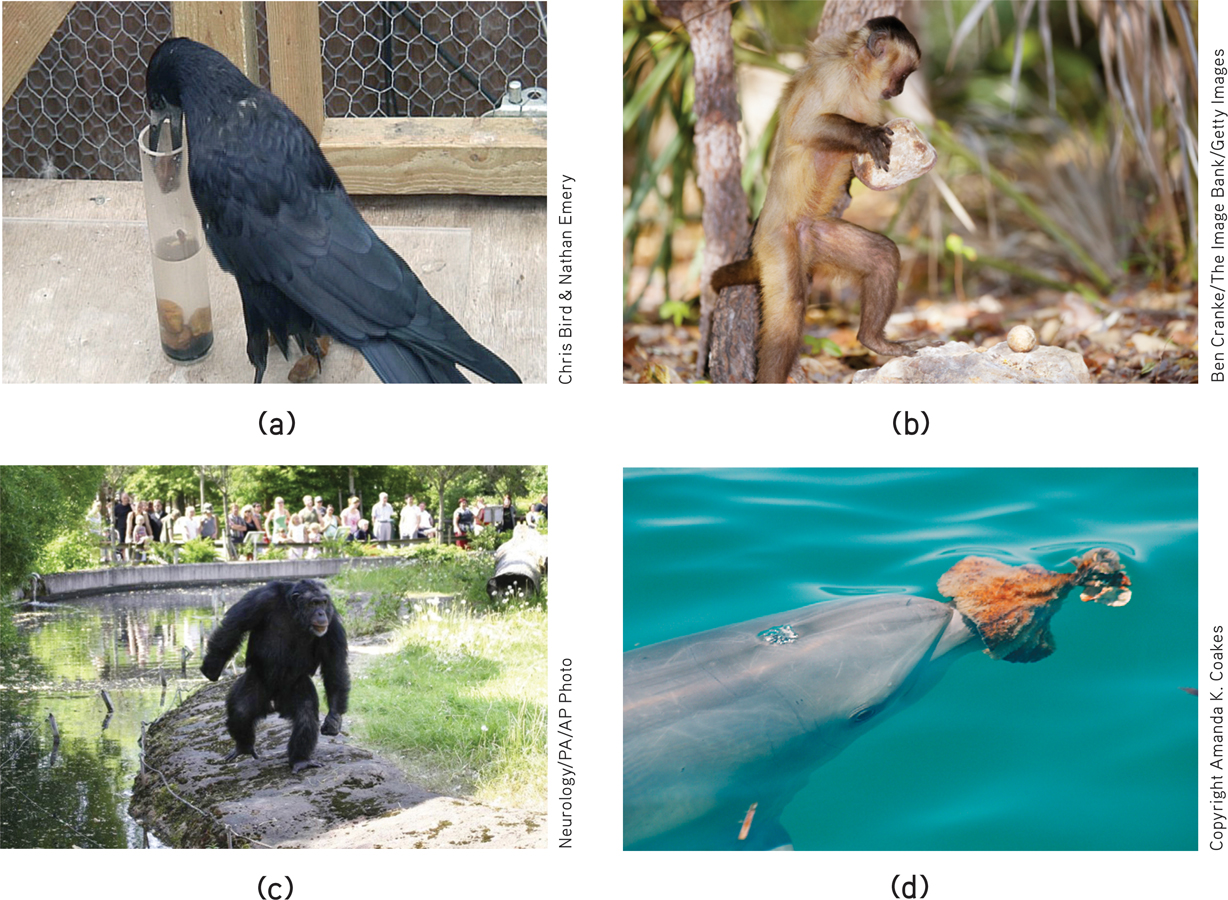

Birds, too, have displayed insight. One experiment, by (yes) Christopher Bird and Nathan Emery (2009), has brought to life an Aesop fable in which a thirsty crow was unable to reach the water in a partly filled pitcher. See its solution in FIGURE 9.8a.

Figure 9.8

Figure 9.8Animal talents (a) Crows studied by Christopher Bird and Nathan Emery (2009) quickly learned to raise the water level in a tube and nab a floating worm by dropping in stones. Other crows have used twigs to probe for insects, and bent strips of metal to reach food. (b) Capuchin monkeys have learned not only to use heavy rocks to crack open palm nuts, but also to test stone hammers and select a sturdier, less crumbly one (Visalberghi et al., 2009). (c) One male chimpanzee in Sweden’s Furuvik Zoo was observed every morning collecting stones into a neat little pile, which later in the day he used as ammunition to pelt visitors (Osvath & Karvonen, 2012). (d) Dolphins form coalitions, cooperatively hunt, and learn tool use from one another (Bearzi & Stanford, 2010). This bottlenose dolphin in Shark Bay, Western Australia, belongs to a small group that uses marine sponges as protective nose guards when probing the sea floor for fish (Krützen et al., 2005).

Using Tools and Transmitting Culture

Like humans, many other species invent behaviors and transmit cultural patterns to their peers and offspring (Boesch-

Researchers have found at least 39 local customs related to chimpanzee tool use, grooming, and courtship (Claidière & Whiten, 2012; Whiten & Boesch, 2001). One group may slurp termites directly from a stick, another group may pluck them off individually. One group may break nuts with a stone hammer, their neighbors with a wooden hammer. These group differences, along with differing communication and hunting styles, are the chimpanzee version of cultural diversity. Several experiments have brought chimpanzee cultural transmission into the laboratory (Horner et al., 2006). If Chimpanzee A obtains food either by sliding or by lifting a door, Chimpanzee B will then typically do the same to get food. And so will Chimpanzee C after observing Chimpanzee B. Across a chain of six animals, chimpanzees see, and chimpanzees do.

369

Other Cognitive Skills

A baboon knows everyone’s voice within its 80-

There is no question that other species display many remarkable cognitive skills. But one big question remains: Do they, like humans, exhibit language? In the next section, we’ll first consider what language is and how it develops.

***

Returning to our debate about how deserving we humans are of our name Homo sapiens, let’s pause to issue an interim report card. On decision making and risk assessment, our error-

REVIEW: Thinking

|

REVIEW | Thinking |

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Take a moment to answer each of these Learning Objective Questions (repeated here from within this section). Then click the 'show answer' button to check your answers. Research suggests that trying to answer these questions on your own will improve your long-term retention (McDaniel et al., 2009).

9-

Cognition refers to all the mental activities associated with thinking, knowing, remembering, and communicating. We use concepts, mental groupings of similar objects, events, ideas, or people, to simplify and order the world around us. We form most concepts around prototypes, or best examples of a category.

9-

An algorithm is a methodical, logical rule or procedure (such as a step-by-step description for evacuating a building during a fire) that guarantees a solution to a problem. A heuristic is a simpler strategy (such as running for an exit if you smell smoke) that is usually speedier than an algorithm but is also more error prone. Insight is not a strategy-based solution, but rather a sudden flash of inspiration that solves a problem.

Obstacles to problem solving include confirmation bias, which predisposes us to verify rather than challenge our hypotheses, and fixation, such as mental set, which may prevent us from taking the fresh perspective that would lead to a solution.

9-

Intuition is the effortless, immediate, automatic feelings or thoughts we often use instead of systematic reasoning. Heuristics enable snap judgments. Using the availability heuristic, we judge the likelihood of things based on how readily they come to mind, which often leads us to fear the wrong things. Overconfidence can lead us to overestimate the accuracy of our beliefs. When a belief we have formed and explained has been discredited, belief perseverance may cause us to cling to that belief. A remedy for belief perseverance is to consider how we might have explained an opposite result. Framing is the way a question or statement is worded. Subtle wording differences can dramatically alter our responses.

9-

We tend to be afraid of what our ancestral history has prepared us to fear (thus, snakes instead of cigarettes); what we cannot control (flying instead of driving); what is immediate (the takeoff and landing of flying instead of countless moments of trivial danger while driving); and what is most readily available (vivid images of air disasters instead of countless safe car trips).

9-

As people gain expertise, they grow adept at making quick, shrewd judgments. Smart thinkers welcome their intuitions (which are usually adaptive), but when making complex decisions they gather as much information as possible and then take time to let their two-track mind process all available information.

9-

Creativity, the ability to produce novel and valuable ideas, correlates somewhat with aptitude, but is more than school smarts. Aptitude tests require convergent thinking, but creativity requires divergent thinking. Robert Sternberg has proposed that creativity has five components: expertise; imaginative thinking skills; a venturesome personality; intrinsic motivation; and a creative environment that sparks, supports, and refines creative ideas.

9-

Researchers make inferences about other species’ consciousness and intelligence based on behavior. Evidence from studies of various species shows that other animals use concepts, numbers, and tools and that they transmit learning from one generation to the next (cultural transmission). And, like humans, other species also show insight, self-awareness, altruism, cooperation, and grief.

TERMS AND CONCEPTS TO REMEMBER

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE Match each of the terms on the left with its definition on the right. Click on the term first and then click on the matching definition. As you match them correctly they will move to the bottom of the activity.

Question

JpXspKTy1mzUBKpFHf+LaTLZcozsK3Lpe7/XmbF8oMiP0L8pZil1K8qPbeB3oPJzE+95sUBdsVazees59G76tqAQXZgGUPzVFzazkuCGQzMOVvJgIFbfQfjxNzd8edeDRkcJbsqzfBp1EkW/iRW1gVALvyY9/QK0kCFSokeTvbjFmqb+Q9u+5XOaJt9IQ4FqBZN2QhTOmwyu2lwKKnJTzC0jrqBFCfUiWtfrtbWe2xTZuvACqVEz+GR6IpkcJl/X8/6NwSxNvjYzPNfZTuizVEASjNRFSfPldHuplWeNCQWp2ALtUYbDfJlWZJN+kauTL+bikqULYwWY+3aNlracZ6lVWEZPrLoamaTLvCmYbYG+D8V+gHqe/TCdMe0koqq1iCY0mYOMxapucoMcV4jRVdXSz2pKUhWvD7sAUGo4NnmwmhQkBRxuucoM0uzGEQD6LBo4sSHwKEx9SS9v5ZON2nO/0B6uv84pz3ykM5K7nrFvZf3c948882N30LpMVLxbiFYuPs4OVGoB70X7ckRiKfnY5Y5SlNQtStG+hq4FYbWONgk5AzyJMzR9yGVAGyg08bt3GxlGv1AFEf5QHC/lvWmR9USwdLjDe7W9aWE1DkwGh7X9cD2aCayWdmPr6WahwqcMfG07xI45o7JO2qlZMVzt23J8s/ctQ1MjfkgXS3Glsjj6QH1AGmu64B8B7imncPBfYFSEw8iv34Rf5DuKeq7nrIi6aoZcje5fUGBEDcjWUr3PtFrPPXuKBBTZy89br1AhA0YyDGi/d2zvsPzZIwapBqMUhGWJ3gfktxITL/9E26h7Q3HsoJ4a3Ph8AJMkOgQX5W0isJZ4+xAe62CA0foq9IsArFIpzeFJH7qtCbecby8p7apvlpzWWKUdUaKo695uETmUlDq/Yiw2Q314mRbDY99EL8Chm21jYS8SHnrwcSM8L2PPa896ZddT/BPY9h7TC5JCI30aPFBVpkrlCMIijavDJjBPHpE0XUgI6mcocs3DTo51MBgo++MI1F6TmU9cHfEmCZR4Y/VmHhDXy+6jZJOHVa7DD9gYNHDrkV9juBIucZq1TWf7eLWlZyeHPLGPchcOBCIx24l1noJu6c5j+PJJT8DFhWLnC6K+FyE5+D8nIrffTGuuuA8VvQ5Wy481K1gX5LDmg9E3hztWlav5MWZz8Zd8vqAV85Mlj1OK5h8A8Vi96WppJTNU58kXo2hsfaZUYLFx4iCsy48np17z9UwjVkdh9c/Ez+baj3Tj3IOk0+MGIScn5k7Mt5E52zoM2LCt1oP0jMMKgjUT4hsnS3dz28ZgI7i18NrQtBmyLrndu87Zx4vqmMBtWsV6O0fIVc0E94OBGl52502SJYono8pah20vPSuNqB/7FevqBygSIOVHN4h41UsSP2ve654L2V2yIrrUBQSCrHlb2Z2MAODeFXtSiaJZ+xznG4TtfB9THqi/XR3Prgahhswy4FqGfQLF97i2K2Td1N/BNtSU2j/KgUt9ckx4D6/HxIeoV7lQ95ALGB1by/W3Gz3/+E4gZ5VkWmEanNNUTWnKcn4ijL2n8d0JZ/BLLZu+eR3D9cn9Ge620N+DwrdC/ifXXfzhDPVCuw+vheLkWBCdQ25VMN8QfPZIBwioUXHlKcADzhfUAuM+a2lNZ4xbDUibCWzHitjBwZSkPHJbaIgxqUlEnip0E3/wXdd+qnpTfvWLONsWjRb74v1pneLAZnvhyQp0jjFB635+ne5kG9JfhVD0tkxzUEoZfiKBziz2aSufJe7Lvbf6p8MSadNVznvLNvQ8UL1B7VS9ykQ1aNy/nqoK4D2SQWhMdjdVjBuei1SqtvVKhbMA9Xk00PgidPnwVkhhIZkkYPGN6MqTXxQdL6V4W70Ut3u1DfxzEujNsBz4q9QuEfsQt31QYF2AH4Q2iI7lbHvcnkXYJT/iT0oIG90AE2PF5mzc8M9aZxw5TObxXntJ9Uvo1jXBkR3rmOZaD5C6goqDhvdGQHD5YVjCVfan12NeVkdSlgITE/Hp/gYNaX2C35CTdSac7LepIcqa2eOT1MwGDhMFcNhn52g4CJiU1Ex8kJOTG7ziRDYB1BQevvUjNkAiXycOfHIy8aUr/5kuyW2CurvSh8FDRX4wlwLX+GSYlM54N5JGQjuWCDPDXNn3yNoz5cZjr+Olok05TYsLLtsJEyjvMNhB/jn015fmx6Crsiie2XaC5VIaiVvK9jRg5JifXKcfAnvjj7YhWAXHGM6R5CKMkdXeUW8cKyiF9i7BcFNmnem9blkBIjqw0GCf2/Czu407VJrSIB3Mgjgc2kRzSSPSJi2dsxL41PGvNwCDD/c+Idib0Yjj0I8blM5aPy/yf0ojhJ1Y81ukf+zOHHMdeLJsavqzSHKOZpdhGPG/poDQ8h4agwHDfjeUqYp5lZhzxA9BYJp0jaWcrOUmqghtz4BfKVfSevFzPqa2eTSp7mWetmxNVe6ceptKLdYKBxZ9tZVd66WPnE4+hQcPGUEkhlS5K9uPUwdfVjODmDgAfEKF4kfByAuo5Ey9SCCj7LA5gBOK/lYP6aJX0A2Feza7tKuHSL9N5vRf8BiCFR3azUj8DWzluCJpOGEG8//BSuJND4LFkgBsOShqcxv01gNrlRv+ThjziNTaeXbau4/qRXRak+7ASIVuVN4OPyobl5L4RlaWKOpTTy2tItZLlgnUU7n5l0zH8dq1OdWwz89yKuRJEVZMGFPLs3jElauG1C3KlHSd5AVrIQYz7bDfJOMMB19G5KCqgRky+vy8ULowDriPvc2oIu/Dyj6I9KU51+Ue3qFOeaBClR+doXFhbdcpyRLW614gcaPgI1g57yx+g54Rr0MLGgMDgSkXym69Use  to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in

to create your personalized study plan, which will direct you to the resources that will help you most in  .

.

370