Appendix A Introduction

A-

APPENDIX A

Psychology at Work

.............

A-

Sometimes, Gene Weingarten noted (2002), a humor writer knows “when to just get out of the way.” Here are some sample job titles from the U.S. Department of Labor Dictionary of Occupational Titles: animal impersonator, human projectile, banana ripening-

For most of us, work is life’s biggest single waking activity. To live is to work. Work helps satisfy several levels of need identified in Abraham Maslow’s (1970) hierarchy of needs. Work supports us. Work connects us. Work defines us. Meeting someone for the first time, and wondering who they are, we may ask, “So, what do you do?”

Individuals across various occupations vary in their attitudes toward their work. Some view their work as a job, an unfulfilling but necessary way to make money. Others view their work as a career, an opportunity to advance from one position to a better position. The rest—

Have you ever noticed that when you are immersed in an activity, time flies? And that when you are watching the clock, it seems to move more slowly? French researchers have confirmed that the more we attend to an event’s duration, the longer it seems to last (Couli et al., 2004).

This finding would not surprise Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi [chick-

Csikszentmihalyi formulated the flow concept after studying artists who spent hour after hour painting or sculpting with focused concentration. Immersed in a project, they worked as if nothing else mattered, and then, when finished, they promptly forgot about it. The artists seemed driven less by external rewards—

Csikszentmihalyi’s later observations, of people from varied occupations and countries, and of all ages, confirmed an overriding principle: It’s exhilarating to flow with an activity that fully engages our skills. Flow experiences boost our sense of self-

A-

In many nations work has changed, from farming to manufacturing to knowledge work. More and more work is outsourced to temporary employees and consultants or to workers communicating electronically from off-

industrial-

Industrial-

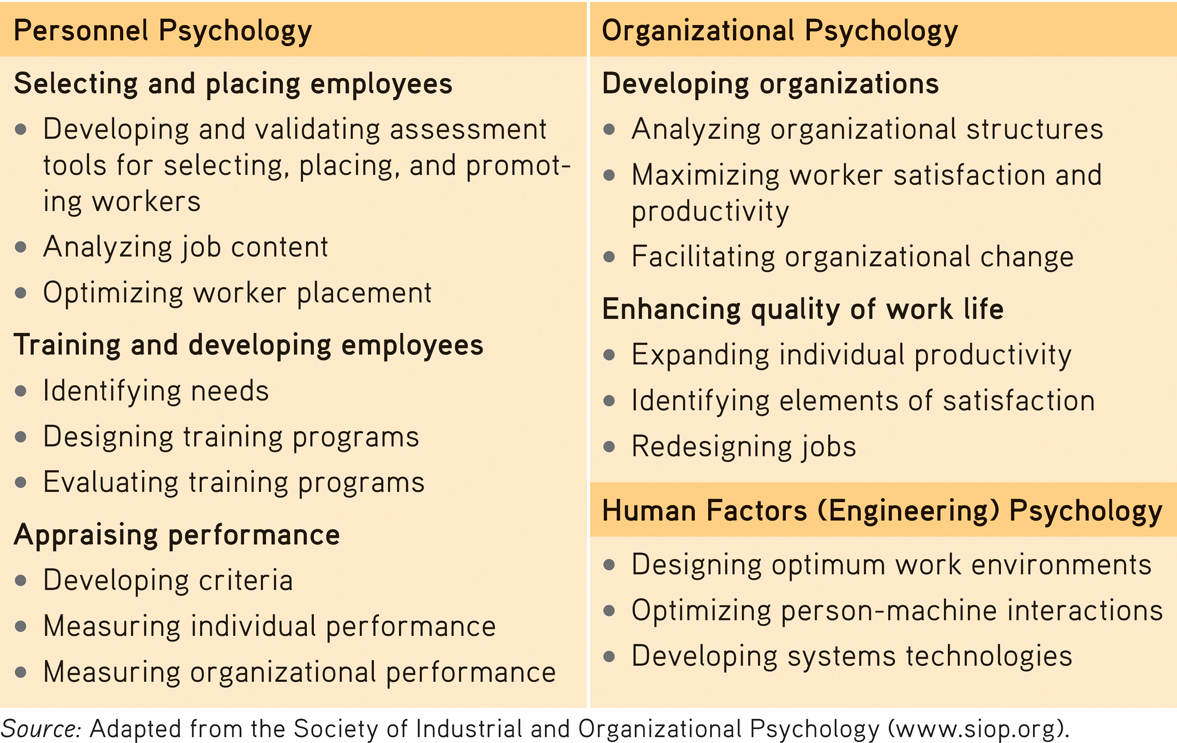

- Personnel psychology applies psychology’s methods and principles to selecting and evaluating workers. Personnel psychologists match people with jobs, by identifying and placing well-

suited candidates. - Organizational psychology considers how work environments and management styles influence worker motivation, satisfaction, and productivity. Organizational psychologists modify jobs and supervision in ways that boost morale and productivity.

organizational psychology an I/O psychology subfield that examines organizational influences on worker satisfaction and productivity and facilitates organizational change.

- Human factorspsychology explores how machines and environments can be optimally designed to fit human abilities. Human factors psychologists study people’s natural perceptions and inclinations to create user-

friendly machines and work settings. Human factorspsychology an I/O psychology subfield that explores how people and machines interact and how machines and physical environments can be made safe and easy to use.

Table A.1

Table A.1I/O Psychology at Work

As scientists, consultants, and management professionals, industrial-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is the value of finding flow in our work?

We become more likely to view our work as fulfilling and socially useful.

A-