10.2 Types of Psychoactive Drugs

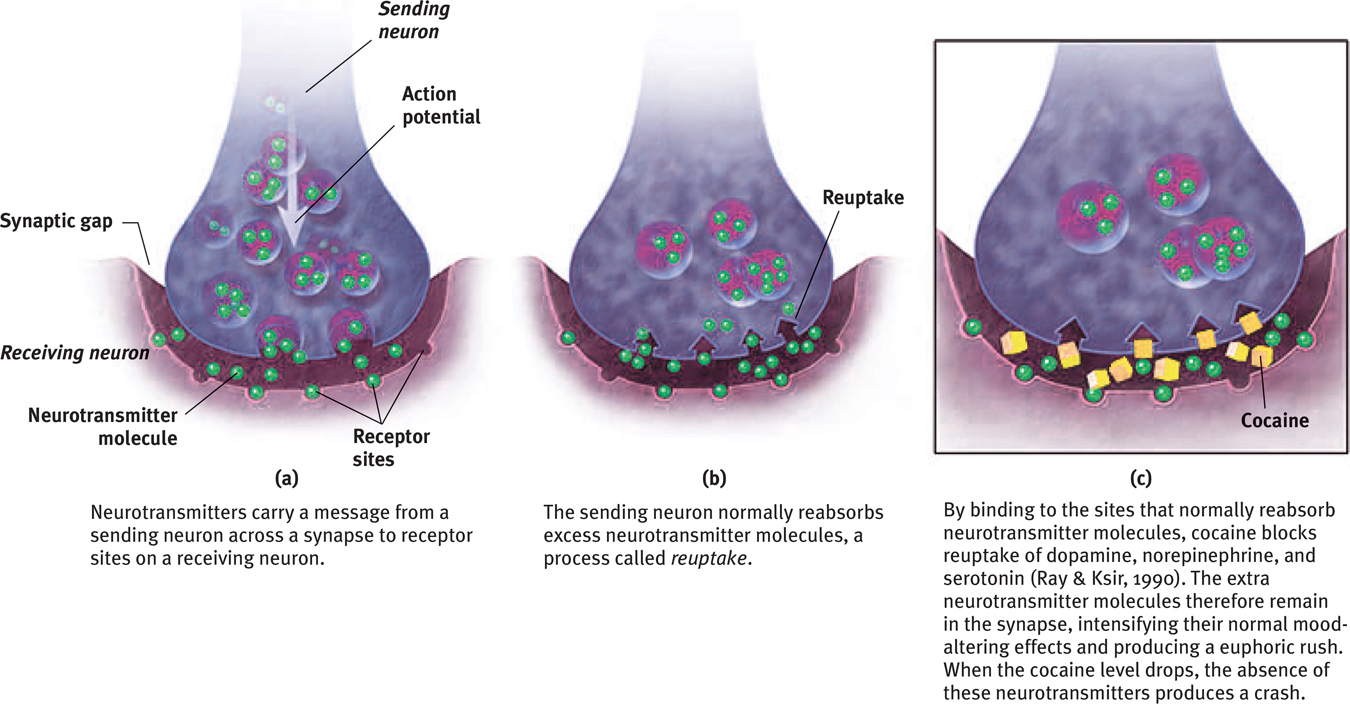

The three major categories of psychoactive drugs are depressants, stimulants, and hallucinogens. All do their work at the brain’s synapses, stimulating, inhibiting, or mimicking the activity of the brain’s own chemical messengers, the neurotransmitters.

Depressants

10-

Depressants are drugs such as alcohol, barbiturates (tranquilizers), and opiates that calm neural activity and slow body functions.

AlcoholTrue or false? In small amounts, alcohol is a stimulant. False. Low doses of alcohol may, indeed, enliven a drinker, but they do so by acting as a disinhibitor—they slow brain activity that controls judgment and inhibitions. Alcohol is an equal-

SLOWED NEURAL PROCESSING Low doses of alcohol relax the drinker by slowing sympathetic nervous system activity. Larger doses cause reactions to slow, speech to slur, and skilled performance to deteriorate. Paired with sleep deprivation, alcohol is a potent sedative. Add these physical effects to lowered inhibitions, and the result can be deadly. Worldwide, several hundred thousand lives are lost each year in alcohol-

MEMORY DISRUPTION Alcohol can disrupt memory formation, and heavy drinking can also have long-

120

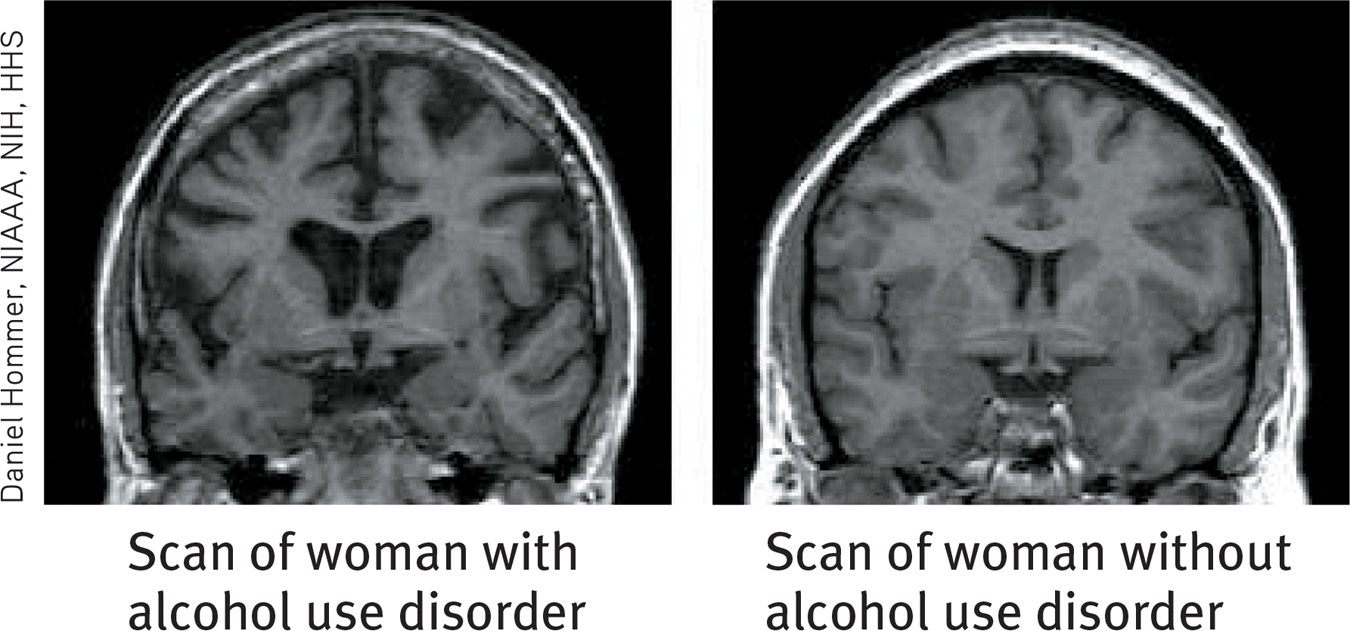

The prolonged and excessive drinking that characterizes alcohol use disorder can shrink the brain (FIGURE 10.2). Women, who have less of a stomach enzyme that digests alcohol, are especially vulnerable (Wuethrich, 2001). Girls and young women can become addicted to alcohol more quickly than boys and young men do, and they are at risk for lung, brain, and liver damage at lower consumption levels (CASA, 2003).

Figure 10.2

Figure 10.2Disordered drinking shrinks the brain MRI scans show brain shrinkage in women with alcohol use disorder (left) compared with women in a control group (right).

REDUCED SELF-AWARENESS AND SELF-CONTROL In one experiment, those who consumed alcohol (rather than a placebo beverage) were doubly likely to be caught mind wandering during a reading task, yet were less likely to notice that they zoned out (Sayette et al., 2009). Alcohol not only reduces self-

Reduced self-

EXPECTANCY EFFECTS As with other psychoactive drugs, expectations influence behavior. When people believe that alcohol affects social behavior in certain ways, and believe they have been drinking alcohol, they will behave accordingly (Moss & Albery, 2009). In a now-

So, alcohol’s effect lies partly in that powerful sex organ, the mind. Fourteen “intervention studies” have educated college drinkers about that very point (Scott-

BarbituratesLike alcohol, the barbiturate drugs, or tranquilizers, depress nervous system activity. Barbiturates such as Nembutal, Seconal, and Amytal are sometimes prescribed to induce sleep or reduce anxiety. In larger doses, they can impair memory and judgment. If combined with alcohol—

OpiatesThe opiates—opium and its derivatives—

121

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How is a “shopping addiction” different from the psychological definition of addiction?

Being strongly interested in something in a way that is not compulsive and dysfunctional is not an addiction. It does not involve obsessive craving in spite of known negative consequences.

- Alcohol, barbiturates, and opiates are all in a class of drugs called _________.

depressants

Stimulants

10-

A stimulant excites neural activity and speeds up body functions. Pupils dilate, heart and breathing rates increase, and blood sugar levels rise, causing a drop in appetite. Energy and self-

Stimulants include caffeine, nicotine, the amphetamines, cocaine, methamphetamine (“speed”), and Ecstasy. People use stimulants to feel alert, lose weight, or boost mood or athletic performance. Unfortunately, stimulants can be addictive, as you may know if you are one of the many who use caffeine daily in your coffee, tea, soda, or energy drinks. Cut off from your usual dose, you may crash into fatigue, headaches, irritability, and depression (Silverman et al., 1992). A mild dose of caffeine typically lasts three or four hours, which—

NicotineCigarettes and other tobacco products deliver highly addictive nicotine. Imagine that cigarettes were harmless—

“There is an overwhelming medical and scientific consensus that cigarette smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease, emphysema, and other serious diseases in smokers. Smokers are far more likely to develop serious diseases, like lung cancer, than nonsmokers.”

Philip Morris Companies Inc., 1999

The lost lives from these dynamite-

For HIV patients who smoke, the virus is now much less lethal than the smoking (Helleberg et al., 2013).

Smoke a cigarette and nature will charge you 12 minutes—

“Smoking cures weight problems … eventually.”

Comedian-writer Steven Wright

Those drawn to nicotine find it very hard to quit, because tobacco products are powerfully and quickly addictive. Attempts to quit even within the first weeks of smoking often fail (DiFranza, 2008). As with other addictions, smokers develop tolerance, and quitting causes withdrawal symptoms, including craving, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, and distractibility. Nicotine-

“To cease smoking is the easiest thing I ever did; I ought to know because I’ve done it a thousand times.”

Mark Twain (1835–1910)

122

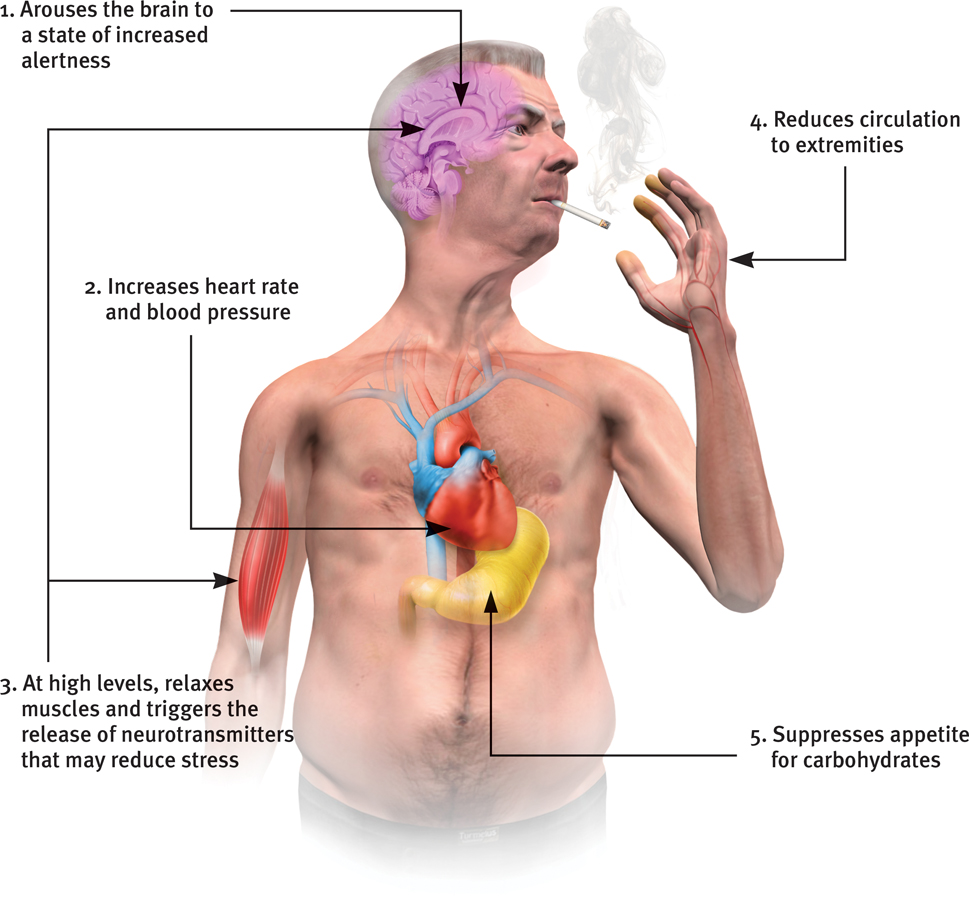

All it takes to relieve this aversive state is a single puff on a cigarette. Within 7 seconds, a rush of nicotine signals the central nervous system to release a flood of neurotransmitters (FIGURE 10.3). Epinephrine and norepinephrine diminish appetite and boost alertness and mental efficiency. Dopamine and opioids temporarily calm anxiety and reduce sensitivity to pain (Ditre et al., 2011; Scott et al., 2004). Thus, ex-

Figure 10.3

Figure 10.3Where there’s smoke … : The physiological effects of nicotine Nicotine reaches the brain within 7 seconds, twice as fast as intravenous heroin. Within minutes, the amount in the blood soars.

These rewards keep people smoking, even among the 3 in 4 smokers who wish they could stop (Newport, 2013). Each year, fewer than 1 in 7 smokers who want to quit will be able to resist. Even those who know they are committing slow-

Humorist Dave Barry (1995) recalling why he smoked his first cigarette the summer he turned 15: “Arguments against smoking: ‘It’s a repulsive addiction that slowly but surely turns you into a gasping, gray-skinned, tumor-ridden invalid, hacking up brownish gobs of toxic waste from your one remaining lung.’ Arguments for smoking: ‘Other teenagers are doing it.’ Case closed! Let’s light up!”

Nevertheless, repeated attempts seem to pay off. Half of all Americans who have ever smoked have quit, sometimes aided by a nicotine replacement drug and with encouragement from a counselor or support group. Success is equally likely whether smokers quit abruptly or gradually (Fiore et al., 2008; Lichtenstein et al., 2010; Lindson et al., 2010). For those who endure, the acute craving and withdrawal symptoms gradually dissipate over the ensuing six months (Ward et al., 1997). After a year’s abstinence, only 10 percent will relapse in the next year (Hughes, 2010). These nonsmokers may live not only healthier but also happier lives. Smoking correlates with higher rates of depression, chronic disabilities, and divorce (Doherty & Doherty, 1998; Edwards & Kendler, 2012; Vita et al., 1998). Healthy living seems to add both years to life and life to years.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What withdrawal symptoms should your friend expect when she finally decides to quit smoking?

Your friend will likely experience strong craving, insomnia, anxiety, irritability, and distractibility. She’ll probably find it harder to concentrate. However, if she sticks with it, the craving and withdrawal symptoms will gradually dissipate over about six months.

123

CocaineCocaine use offers a fast track from euphoria to crash. The recipe for Coca-

Figure 10.4

Figure 10.4Cocaine euphoria and crash

In situations that trigger aggression, ingesting cocaine may heighten reactions. Caged rats fight when given foot shocks, and they fight even more when given cocaine and foot shocks. Likewise, humans who voluntarily ingest high doses of cocaine in laboratory experiments impose higher shock levels on a presumed opponent than do those receiving a placebo (Licata et al., 1993). Cocaine use may also lead to emotional disturbances, suspiciousness, convulsions, cardiac arrest, or respiratory failure.

“Cocaine makes you a new man. And the first thing that new man wants is more cocaine.”

Comedian George Carlin (1937–2008)

In national surveys, 3 percent of U.S. high school seniors and 6 percent of British 18-

Cocaine’s psychological effects depend in part on the dosage and form consumed, but the situation and the user’s expectations and personality also play a role. Given a placebo, cocaine users who thought they were taking cocaine often had a cocaine-

MethamphetamineMethamphetamine is chemically related to its parent drug, amphetamine (NIDA, 2002, 2005) but has greater effects. Methamphetamine triggers the release of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which stimulates brain cells that enhance energy and mood, leading to eight hours or so of heightened energy and euphoria. Its aftereffects may include irritability, insomnia, hypertension, seizures, social isolation, depression, and occasional violent outbursts (Homer et al., 2008). Over time, methamphetamine may reduce baseline dopamine levels, leaving the user with continuing depressed functioning.

124

EcstasyEcstasy, a street name for MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known in its powder form as “Molly”), is both a stimulant and a mild hallucinogen. As an amphetamine derivative, Ecstasy triggers dopamine release, but its major effect is releasing stored serotonin and blocking its reuptake, thus prolonging serotonin’s feel-

During the 1990s, Ecstasy’s popularity soared as a “club drug” taken at nightclubs and all-

Hallucinogens

10-

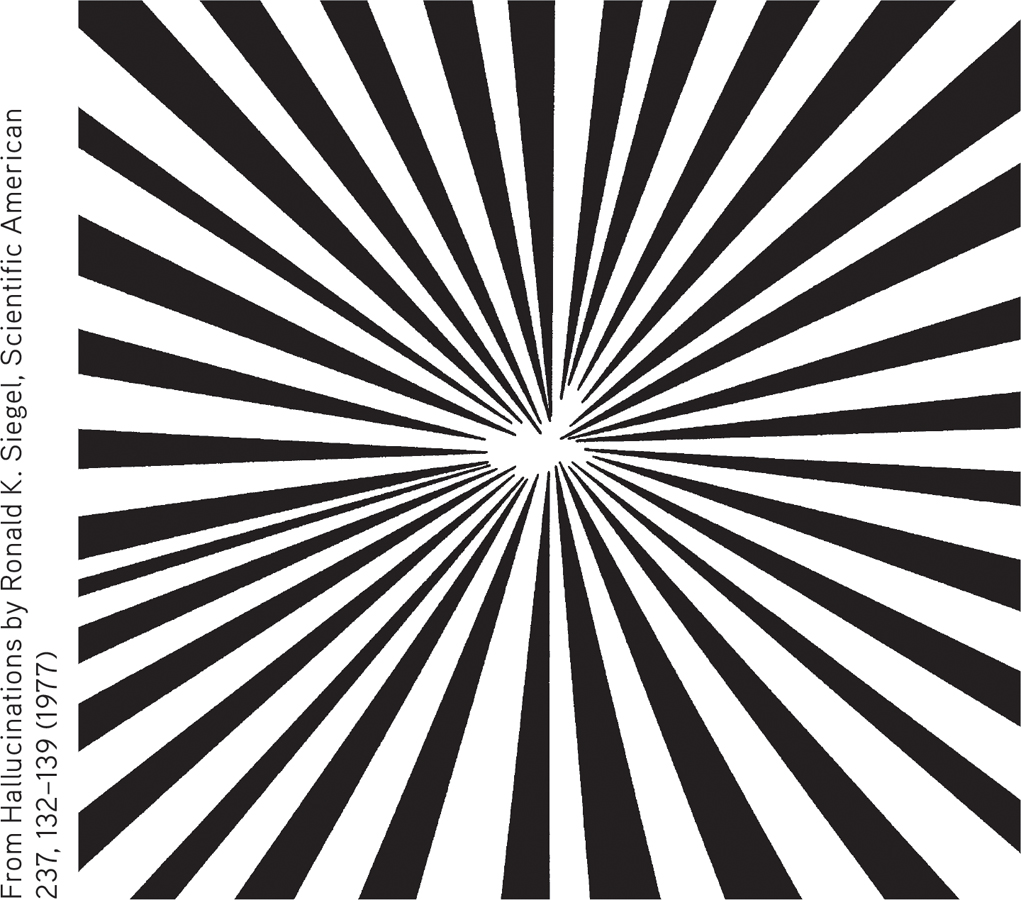

Hallucinogens distort perceptions and evoke sensory images in the absence of sensory input (which is why these drugs are also called psychedelics, meaning “mind-

Whether provoked to hallucinate by drugs, loss of oxygen, or extreme sensory deprivation, the brain hallucinates in basically the same way (Siegel, 1982). The experience typically begins with simple geometric forms, such as a lattice, cobweb, or spiral. The next phase consists of more meaningful images; some may be superimposed on a tunnel or funnel, others may be replays of past emotional experiences. As the hallucination peaks, people frequently feel separated from their body and experience dreamlike scenes so real that they may become panic-

These sensations are strikingly similar to the near-death experience, an altered state of consciousness reported by about 10 to 15 percent of patients revived from cardiac arrest (Agrillo, 2011; Greyson, 2010; Parnia et al., 2013). Many describe visions of tunnels (FIGURE 10.5), bright lights or beings of light, a replay of old memories, and out-

Figure 10.5

Figure 10.5Near-

LSDAlbert Hofmann, a chemist, created—

125

MarijuanaMarijuana leaves and flowers contain THC (delta-

Marijuana is a mild hallucinogen, amplifying sensitivity to colors, sounds, tastes, and smells. But like alcohol, marijuana relaxes, disinhibits, and may produce a euphoric high. Both alcohol and marijuana impair the motor coordination, perceptual skills, and reaction time necessary for safely operating an automobile or other machine. “THC causes animals to misjudge events,” reported Ronald Siegel (1990, p. 163). “Pigeons wait too long to respond to buzzers or lights that tell them food is available for brief periods; and rats turn the wrong way in mazes.”

Marijuana and alcohol also differ. The body eliminates alcohol within hours. THC and its by-

A marijuana user’s experience can vary with the situation. If the person feels anxious or depressed, marijuana may intensify the feelings. The more often the person uses marijuana, especially during adolescence, the greater the risk of anxiety, depression, or addiction (Bambico et al., 2010; Hurd et al., 2013; Murray et al., 2007).

Marijuana also disrupts memory formation and interferes with immediate recall of information learned only a few minutes before (Bossong et al., 2012). Such cognitive effects outlast the period of smoking (Messinis et al., 2006). Heavy adult use for over 20 years is associated with a shrinkage of brain areas that process memories and emotions (Yücel et al., 2008). One study, which has tracked more than 1000 New Zealanders from birth, found that the IQ scores of persistent teen marijuana users dropped eight points from age 13 to 38 (Meier et al., 2012). (This mental decline was seen only in those who started regular use before age 18, while their brains were still rapidly developing.) Prenatal exposure through maternal marijuana use impairs brain development (Berghuis et al., 2007; Huizink & Mulder, 2006).

To review the basic psychoactive drugs and their actions, and to play the role of experimenter as you administer drugs and observe their effects, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Your Mind on Drugs.

To review the basic psychoactive drugs and their actions, and to play the role of experimenter as you administer drugs and observe their effects, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: Your Mind on Drugs.

To free up resources to fight crime, some states and countries have passed laws legalizing the possession of small quantities of marijuana. In some cases, legal medical marijuana use has been granted to relieve the pain and nausea associated with diseases such as AIDS and cancer (Munsey, 2010; Watson et al., 2000). In such cases, the Institute of Medicine recommends delivering the THC with medical inhalers. Marijuana smoke, like cigarette smoke, is toxic and can cause cancer, lung damage, and pregnancy complications (BLF, 2012).

***

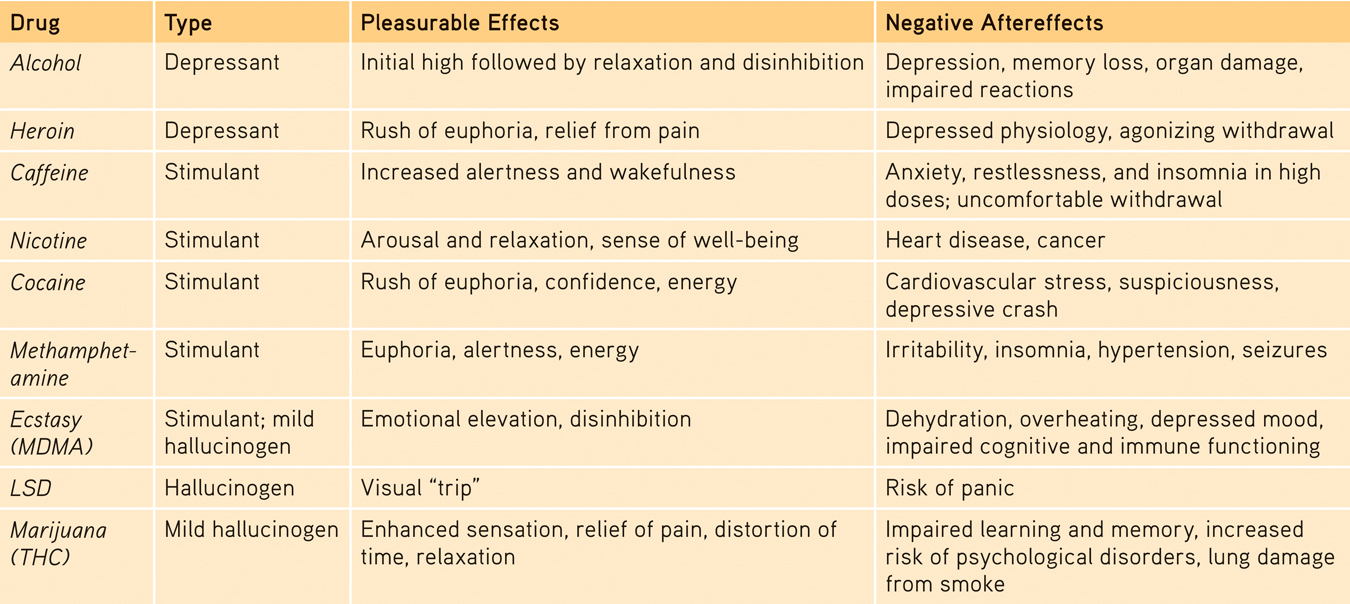

Despite their differences, the psychoactive drugs summarized in TABLE 10.2 share a common feature: They trigger negative aftereffects that offset their immediate positive effects and grow stronger with repetition. And that helps explain both tolerance and withdrawal. As the opposing, negative aftereffects grow stronger, it takes larger and larger doses to produce the desired high (tolerance), causing the after-

Table 10.2

Table 10.2A Guide to Selected Psychoactive Drugs

126

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

“How strange would appear to be this thing that men call pleasure! And how curiously it is related to what is thought to be its opposite, pain! … Wherever the one is found, the other follows up behind.”

Plato, Phaedo, fourth century b.c.e.

- How does this pleasure-pain description apply to the repeated use of psychoactive drugs?

Psychoactive drugs create pleasure by altering brain chemistry. With repeated use of the drug, the brain develops tolerance and needs more of the drug to achieve the desired effect. (Marijuana is an exception.) Discontinuing use of the substance then produces painful or psychologically unpleasant withdrawal symptoms.