11.2 Twin and Adoption Studies

11-2 How do twin and adoption studies help us understand the effects and interactions of nature and nurture?

To scientifically tease apart the influences of heredity and environment, behavior geneticists could wish for two types of experiments. The first would control heredity while varying the home environment. The second would control the home environment while varying heredity. Although such experiments with human infants would be unethical, nature has done this work for us.

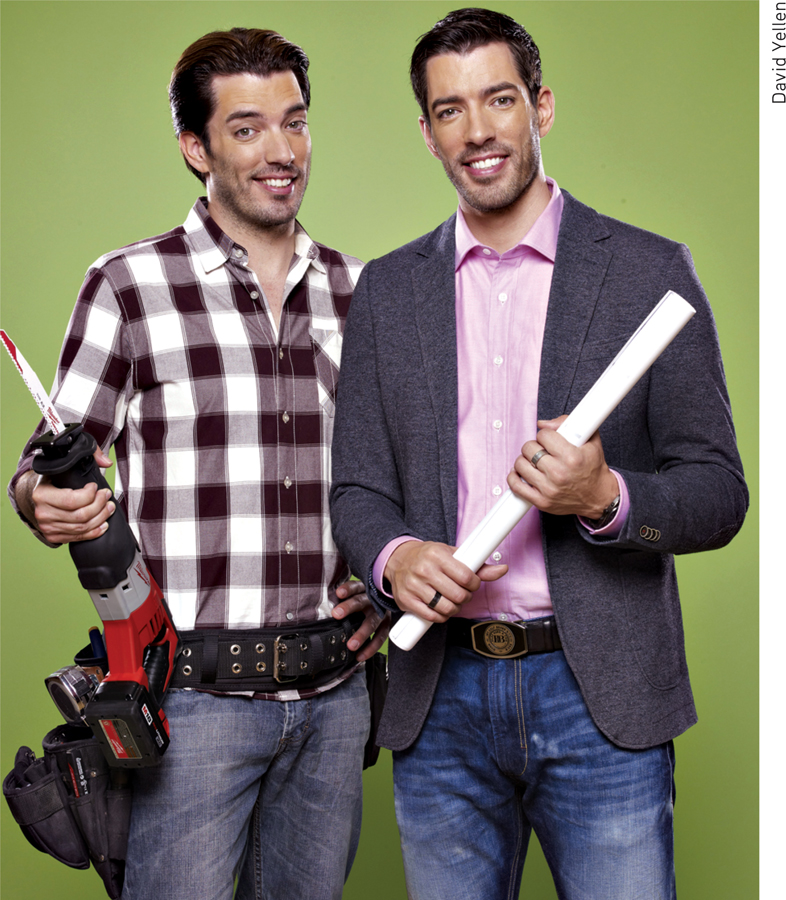

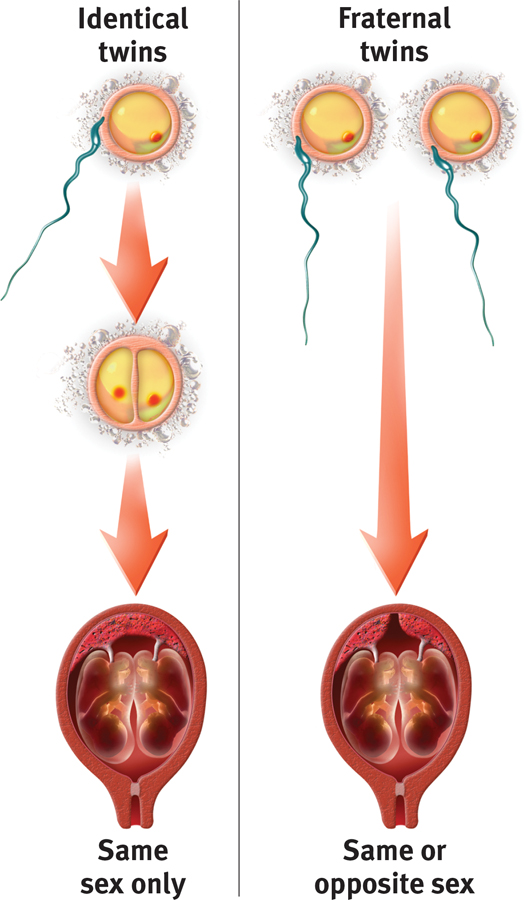

Identical Versus Fraternal Twins

Identical (monozygotic) twins develop from a single fertilized egg that splits in two. Thus they are genetically identical—nature’s own human clones (FIGURE 11.2). Indeed, they are clones who share not only the same genes but the same conception and uterus, and usually the same birth date and cultural history. Two slight qualifications:

136

- Although identical twins have the same genes, they don’t always have the same number of copies of those genes. That variation helps explain why one twin may have a greater risk for certain illnesses and disorders, including schizophrenia (Maiti et al., 2011).

- Most identical twins share a placenta during prenatal development, but one of every three sets has separate placentas. One twin’s placenta may provide slightly better nourishment, which may contribute to identical twin differences (Davis et al., 1995b; Phelps et al., 1997; Sokol et al., 1995).

Figure 11.2

Figure 11.2Same fertilized egg, same genes; different eggs, different genes Identical twins develop from a single fertilized egg, fraternal twins from two.

Fraternal (dizygotic) twins develop from two separate fertilized eggs. As womb-mates, they share a prenatal environment, but they are genetically no more similar than ordinary brothers and sisters.

Shared genes can translate into shared experiences. A person whose identical twin has autism spectrum disorder, for example, has about a 3 in 4 risk of being similarly diagnosed. If the affected twin is fraternal, the co-twin has about a 1 in 3 risk (Ronald & Hoekstra, 2011). To study the effects of genes and environments, hundreds of researchers have studied some 800,000 identical and fraternal twin pairs (Johnson et al., 2009).

Are identical twins also behaviorally more similar than fraternal twins? Studies of thousands of twin pairs in Germany, Australia, and the United States have found that on the personality traits of extraversion (outgoingness) and neuroticism (emotional instability) identical twins report much greater similarity than do fraternal twins (Kandler et al., 2011; Laceulle et al., 2011; Loehlin, 2012). Genes also influence many specific behaviors. For example, compared with rates for fraternal twins, drinking and driving convictions are 12 times greater among those who have an identical twin with such a conviction (Beaver & Barnes, 2012). As twins grow older, their behaviors remain similar (McGue & Christensen, 2013).

Identical twins, more than fraternal twins, also report being treated alike. So, do their experiences rather than their genes account for their similarities? No. Studies have shown that identical twins whose parents treated them alike (for example, dressing them identically) were not psychologically more alike than identical twins who were treated less similarly (Kendler et al., 1994; Loehlin & Nichols, 1976). In explaining individual differences, genes matter.

Separated Twins

Twins Lorraine and Levinia Christmas, driving to deliver Christmas presents to each other near Flitcham, England, collided (Shepherd, 1997).

Imagine the following science fiction experiment: A mad scientist decides to separate identical twins at birth, then raise them in differing environments. Better yet, consider a true story:

137

On a chilly February morning in 1979, some time after divorcing his first wife, Linda, Jim Lewis awoke in his modest home next to his second wife, Betty. Determined that this marriage would work, Jim made a habit of leaving love notes to Betty around the house. As he lay in bed he thought about others he had loved, including his son, James Alan, and his faithful dog, Toy.

In 2009, thieves broke into a Berlin store and stole jewelry worth $6.8 million. One thief left a drop of sweat—a link to his genetic signature. Police analyzed the DNA and encountered two matches: The DNA belonged to identical twin brothers. The court ruled that “at least one of the brothers took part in the crime, but it has not been possible to determine which one.” Birds of a feather can rob together.

Jim looked forward to spending part of the day in his basement woodworking shop, where he enjoyed building furniture, picture frames, and other items, including a white bench now circling a tree in his front yard. Jim also liked to spend free time driving his Chevy, watching stock-car racing, and drinking Miller Lite beer.

Jim was basically healthy, except for occasional half-day migraine headaches and blood pressure that was a little high, perhaps related to his chain-smoking habit. He had become overweight a while back but had shed some of the pounds. Having undergone a vasectomy, he was done having children.

What was extraordinary about Jim Lewis, however, was that at that same moment (we are not making this up) there existed another man—also named Jim—for whom all these things (right down to the dog’s name) were also true.1 This other Jim—Jim Springer—just happened, 38 years earlier, to have been his fetal partner. Thirty-seven days after their birth, these genetically identical twins were separated, adopted by blue-collar families, and raised with no contact or knowledge of each other’s whereabouts until the day Jim Lewis received a call from his genetic clone (who, having been told he had a twin, set out to find him).

For a 2-minute synopsis of twin similarity, visit Launch-Pad’s Video—Nature Versus Nurture: Growing Up Apart.

For a 2-minute synopsis of twin similarity, visit Launch-Pad’s Video—Nature Versus Nurture: Growing Up Apart.

One month later, the brothers became the first of many separated twin pairs tested by University of Minnesota psychologist Thomas Bouchard and his colleagues (Miller, 2012). The brothers’ voice intonations and inflections were so similar that, hearing a playback of an earlier interview, Jim Springer guessed “That’s me.” Wrong—it was Jim Lewis. Given tests measuring their personality, intelligence, heart rate, and brain waves, the Jim twins—despite 38 years of separation—were virtually as alike as the same person tested twice. Both married women named Dorothy Jane Scheckelburger. Okay, the last item is a joke. But as Judith Rich Harris (2006) has noted, it is hardly weirder than some other reported similarities.

Aided by publicity in magazine and newspaper stories, Bouchard (2009) and his colleagues located and studied 74 pairs of identical twins raised apart. They continued to find similarities not only of tastes and physical attributes but also of personality (characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and acting), abilities, attitudes, interests, and even fears.

138

Bouchard’s famous twin research was, appropriately enough, conducted in Minneapolis, the “Twin City” (with St. Paul) and home to the Minnesota Twins baseball team.

In Sweden, researchers identified 99 separated identical twin pairs and more than 200 separated fraternal twin pairs (Pedersen et al., 1988). Compared with equivalent samples of identical twins raised together, the separated identical twins had somewhat less identical personalities. Still, separated twins were more alike if genetically identical than if fraternal. And separation shortly after birth (rather than, say, at age 8) did not amplify their personality differences.

Coincidences are not unique to twins. Patricia Kern of Colorado was born March 13, 1941, and named Patricia Ann Campbell. Patricia DiBiasi of Oregon also was born March 13, 1941, and named Patricia Ann Campbell. Both had fathers named Robert, worked as bookkeepers, and at the time of this comparison had children ages 21 and 19. Both studied cosmetology, enjoyed oil painting as a hobby, and married military men, within 11 days of each other. They are not genetically related. (From an AP report, May 2, 1983.)

Stories of startling twin similarities have not impressed critics, who remind us that “The plural of anecdote is not data.” They have noted that if any two strangers were to spend hours comparing their behaviors and life histories, they would probably discover many coincidental similarities. If researchers created a control group of biologically unrelated pairs of the same age, sex, and ethnicity, who had not grown up together but who were as similar to one another in economic and cultural background as are many of the separated twin pairs, wouldn’t these pairs also exhibit striking similarities (Joseph, 2001)? Twin researchers have replied that separated fraternal twins do not exhibit similarities comparable to those of separated identical twins.

Even the impressive data from personality assessments are clouded by the reunion of many of the separated twins some years before they were tested. Moreover, identical twins share an appearance, and the responses it evokes. Adoption agencies also tend to place separated twins in similar homes. Despite these criticisms, the striking twin-study results helped shift scientific thinking toward a greater appreciation of genetic influences.

Biological Versus Adoptive Relatives

For behavior geneticists, nature’s second real-life experiment—adoption—creates two groups: genetic relatives (biological parents and siblings) and environmental relatives (adoptive parents and siblings). For personality or any other given trait, we can therefore ask whether adopted children are more like their biological parents, who contributed their genes, or their adoptive parents, who contribute a home environment. While sharing that home environment, do adopted siblings also come to share traits?

The stunning finding from studies of hundreds of adoptive families is that people who grow up together, whether biologically related or not, do not much resemble one another in personality (McGue & Bouchard, 1998; Plomin, 2011; Rowe, 1990). In personality traits such as extraversion and agreeableness, people who have been adopted are more similar to their biological parents than to their caregiving adoptive parents.

The finding is important enough to bear repeating: The environment shared by a family’s children has virtually no discernible impact on their personalities. Two adopted children raised in the same home are no more likely to share personality traits with each other than with the child down the block. Heredity shapes other primates’ personalities, too. Macaque monkeys raised by foster mothers exhibited social behaviors that resemble their biological, rather than foster, mothers (Maestripieri, 2003). Add in the similarity of identical twins, whether they grow up together or apart, and the effect of a shared raising environment seems shockingly modest.

What we have here is perhaps “the most important puzzle in the history of psychology,” contended Steven Pinker (2002): Why are children in the same family so different? Why does shared family environment have so little effect on children’s personalities? Is it because each sibling experiences unique peer influences and life events? Because sibling relationships ricochet off each other, amplifying their differences? Because siblings—despite sharing half their genes—have very different combinations of genes and may evoke very different kinds of parenting? Such questions fuel behavior geneticists’ curiosity.

“Mom may be holding a full house while Dad has a straight flush, yet when Junior gets a random half of each of their cards his poker hand may be a loser.”

David Lykken (2001)

The genetic leash may limit the family environment’s influence on personality, but it does not mean that adoptive parenting is a fruitless venture. Parents do influence their children’s attitudes, values, manners, politics, and faith (Reifman & Cleveland, 2007). Religious involvement is genetically influenced (Steger et al., 2011). But a pair of adopted children or identical twins will, especially during adolescence, have more similar religious beliefs if raised together (Koenig et al., 2005). Parenting matters!

139

Moreover, in adoptive homes, child neglect and abuse and even parental divorce are rare. (Adoptive parents are carefully screened; natural parents are not.) So it is not surprising that studies have shown that, despite a somewhat greater risk of psychological disorder, most adopted children thrive, especially when adopted as infants (Loehlin et al., 2007; van IJzendoorn & Juffer, 2006; Wierzbicki, 1993). Seven in eight adopted children have reported feeling strongly attached to one or both adoptive parents. As children of self-giving parents, they have grown up to be more self-giving and altruistic than average (Sharma et al., 1998). Many scored higher than their biological parents on intelligence tests, and most grew into happier and more stable adults. In one Swedish study, children adopted as infants grew up with fewer problems than were experienced by children whose biological mothers initially registered them for adoption but then decided to raise the children themselves (Bohman & Sigvardsson, 1990). Regardless of personality differences between adoptive family members, most adopted children benefit from adoption.

140

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How do researchers use twin and adoption studies to learn about psychological principles?

Researchers use twin and adoption studies to understand how much variation among individuals is due to genetic makeup and how much to environmental factors. Some studies compare the traits and behaviors of identical twins (same genes) and fraternal twins (different genes, as in any two siblings). They also compare adopted children with their adoptive and biological parents. Some studies compare traits and behaviors of twins raised together or separately.