13.4 Reflections on Nature, Nurture, and Their Interaction

13-

“There are trivial truths and great truths,” reflected the physicist Niels Bohr on the paradoxes of science. “The opposite of a trivial truth is plainly false. The opposite of a great truth is also true.” Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. The unique gene combination created when our mother’s egg engulfed our father’s sperm predisposed both our shared humanity and our individual differences. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

171

But our experiences also shape us. Our families and peer relationships teach us how to think and act. Differences initiated by our nature may be amplified by our nurture. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference through norms that shower benefits on macho men and gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. Roles remake their players. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength is becoming increasingly less important for power and status (think Mark Zuckerberg and Hillary Clinton). From 1960 into the next century, women soared from 6 percent to nearly 50 percent of U.S. medical school graduates (AAMC, 2012). In the mid-

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

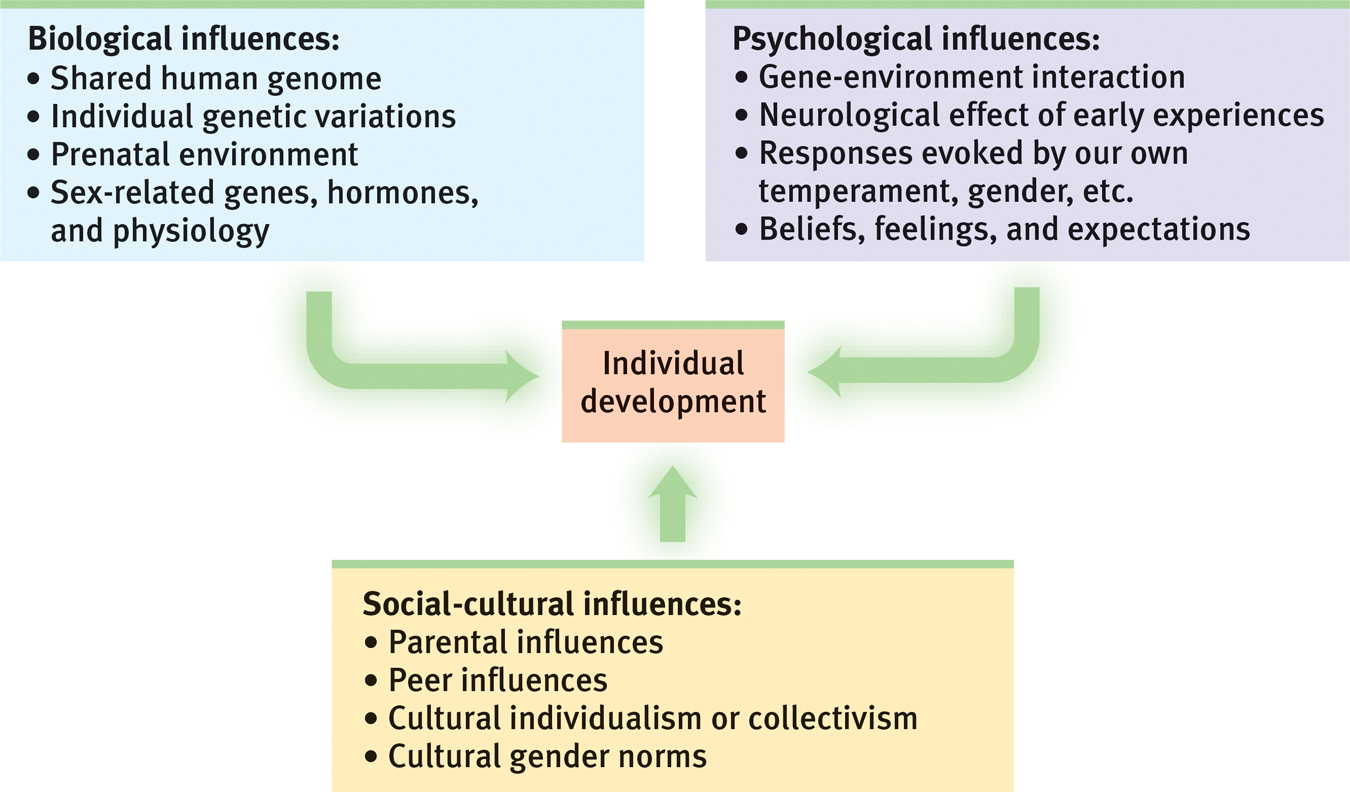

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we are also an open system (FIGURE 13.7). Genes are all-

Figure 13.7

Figure 13.7The bio psycho social approach to development

We can’t excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both the creatures and the creators of our worlds. So many things about us—

172

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- How does the biopsychosocial approach explain our individual development?

The biopsychosocial approach considers all the factors that influence our individual development: biological factors (including evolution and our genes, hormones, and brain), psychological factors (including our experiences, beliefs, feelings, and expectations), and social-

“Let’s hope that it’s not true; but if it is true, let’s hope that it doesn’t become widely known.”

Lady Ashley, commenting on Darwin’s theory

We know from our correspondence and from surveys that some readers feel troubled by the naturalism and evolutionism of contemporary science. (Readers from other nations bear with us, but in the United States there is a wide gulf between scientific and lay thinking about evolution.) “The idea that human minds are the product of evolution is … unassailable fact,” declared a 2007 editorial in Nature, a leading science journal. That sentiment concurs with a 2006 statement of “evidence-

When Isaac Newton explained the rainbow in terms of light of differing wavelengths, the British poet John Keats feared that Newton had destroyed the rainbow’s mysterious beauty. Yet, as Richard Dawkins (1998) noted in Unweaving the Rainbow, Newton’s analysis led to an even deeper mystery—

When Galileo assembled evidence that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa, he did not offer irrefutable proof for his theory. Rather, he offered a coherent explanation for a variety of observations, such as the changing shadows cast by the Moon’s mountains. His explanation eventually won the day because it described and explained things in a way that made sense, that hung together. Darwin’s theory of evolution likewise is a coherent view of natural history. It offers an organizing principle that unifies various observations.

“Is it not stirring to understand how the world actually works—that white light is made of colors, that color measures light waves, that transparent air reflects light … ? It does no harm to the romance of the sunset to know a little about it.”

Carl Sagan, Skies of Other Worlds, 1988

173

Collins is not the only person of faith to find the scientific idea of human origins congenial with his spirituality. In the fifth century, St. Augustine (quoted by Wilford, 1999) wrote, “The universe was brought into being in a less than fully formed state, but was gifted with the capacity to transform itself from unformed matter into a truly marvelous array of structures and life forms.” Some 1600 years later, Pope John Paul II in 1996 welcomed a science-

Meanwhile, many people of science are awestruck at the emerging understanding of the universe and the human creature. It boggles the mind—

What caused this almost-

“The causes of life’s history [cannot] resolve the riddle of life’s meaning.”

Stephen Jay Gould, Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life, 1999

Rather than fearing science, we can welcome its enlarging our understanding and awakening our sense of awe. In The Fragile Species, Lewis Thomas (1992) described his utter amazement that the Earth in time gave rise to bacteria and eventually to Bach’s Mass in B Minor. In a short 4 billion years, life on Earth has come from nothing to structures as complex as a 6-

174