A.3 The Human Factor

The Human Factor

The Human Factor

A-5 How do human factors psychologists work to create user-friendly machines and work settings?

Designs sometimes neglect the human factor. Psychologist Donald Norman bemoaned the complexity of assembling his new HDTV, related components, and seven remotes into a usable home theater system: “I was VP of Advanced Technology at Apple. I can program dozens of computers in dozens of languages. I understand television, really, I do…. It doesn’t matter: I am overwhelmed.”

How much easier life might be if engineers would routinely test their designs and instructions on real people. Human factors psychologists work with designers and engineers to tailor appliances, machines, and work settings to our natural perceptions and inclinations. Bank ATM machines are internally more complex than remote controls ever were, yet, thanks to human factors engineering, ATMs are easier to operate. Digital recorders have solved the TV recording problem with a simple select-and-click menu system (“record that one”). Apple has similarly engineered easy usability with the iPhone and iPad.

Norman (2001) hosts a website (www.jnd.org) that illustrates good designs that fit people (FIGURE A.4). Human factors psychologists also help design efficient environments. An ideal kitchen layout, researchers have found, puts needed items close to their usage point and near eye level. It locates work areas to enable doing tasks in order, such as placing the refrigerator, stove, and sink in a triangle. It creates counters that enable hands to work at or slightly below elbow height (Boehm-Davis, 2005).

Figure A.4

Figure A.4

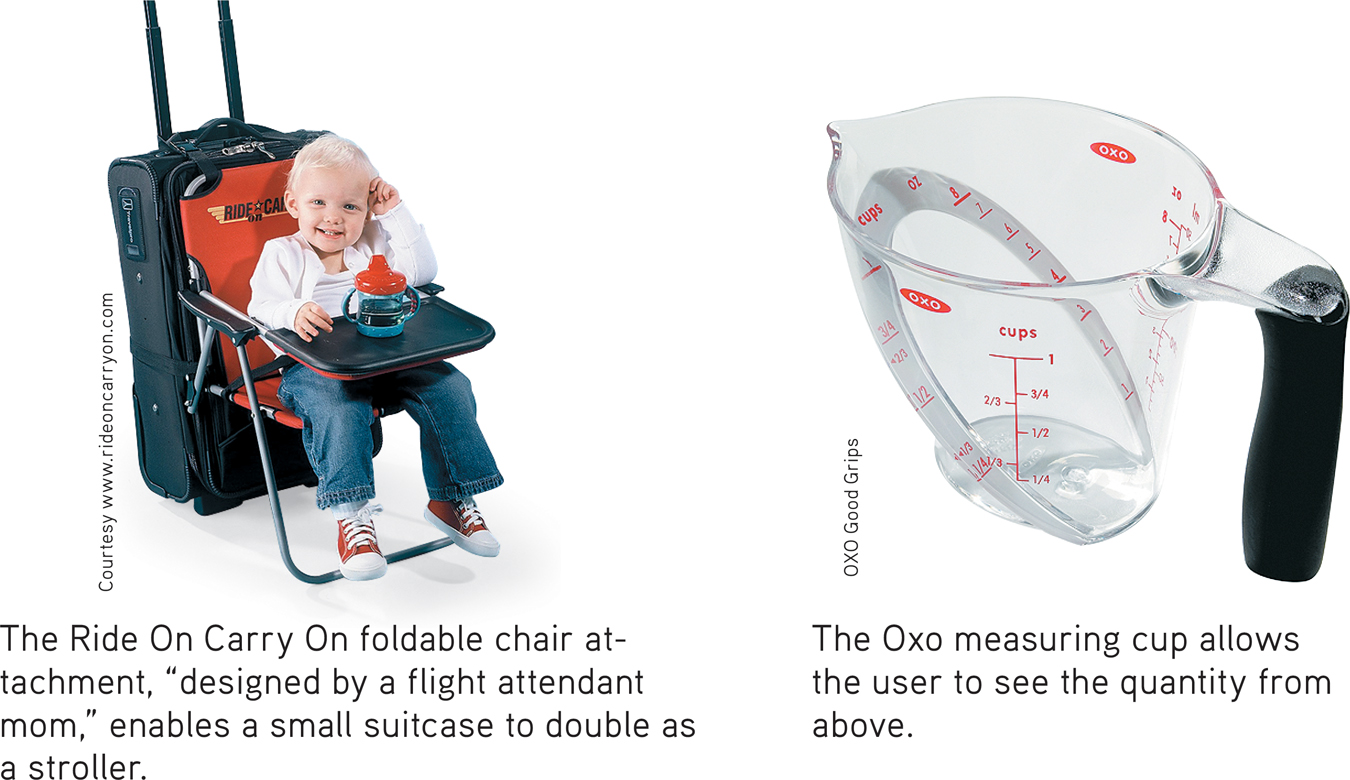

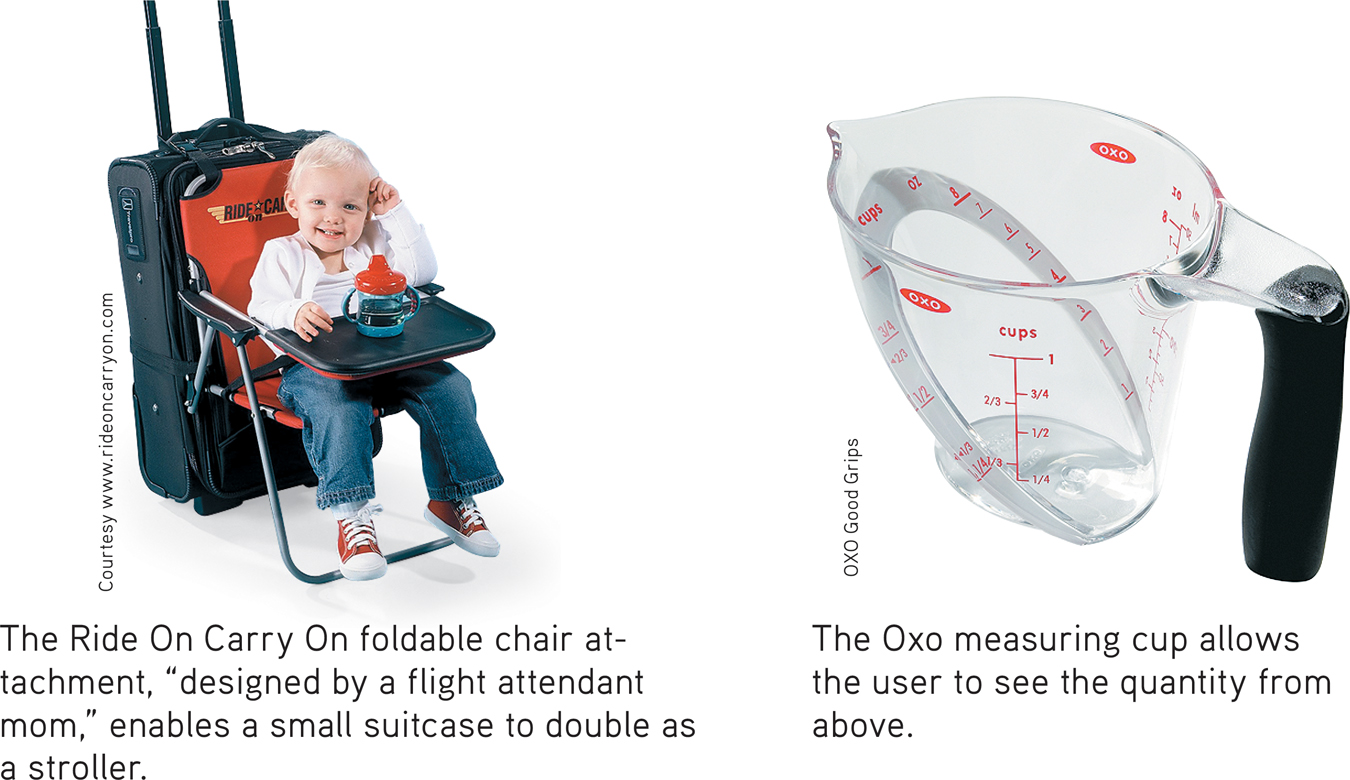

Designing products that fit people Human factors psychologist Donald Norman offers these and other examples of effectively designed products.

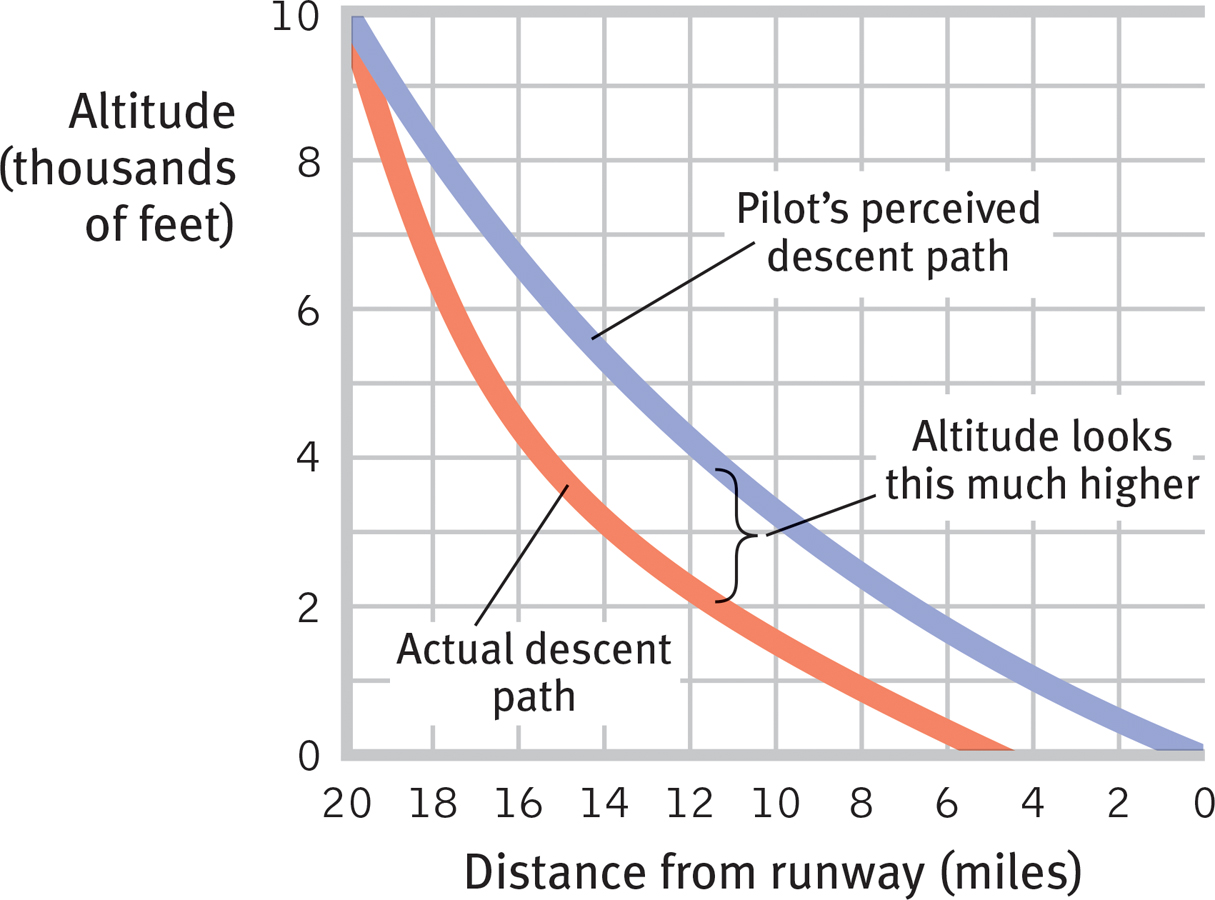

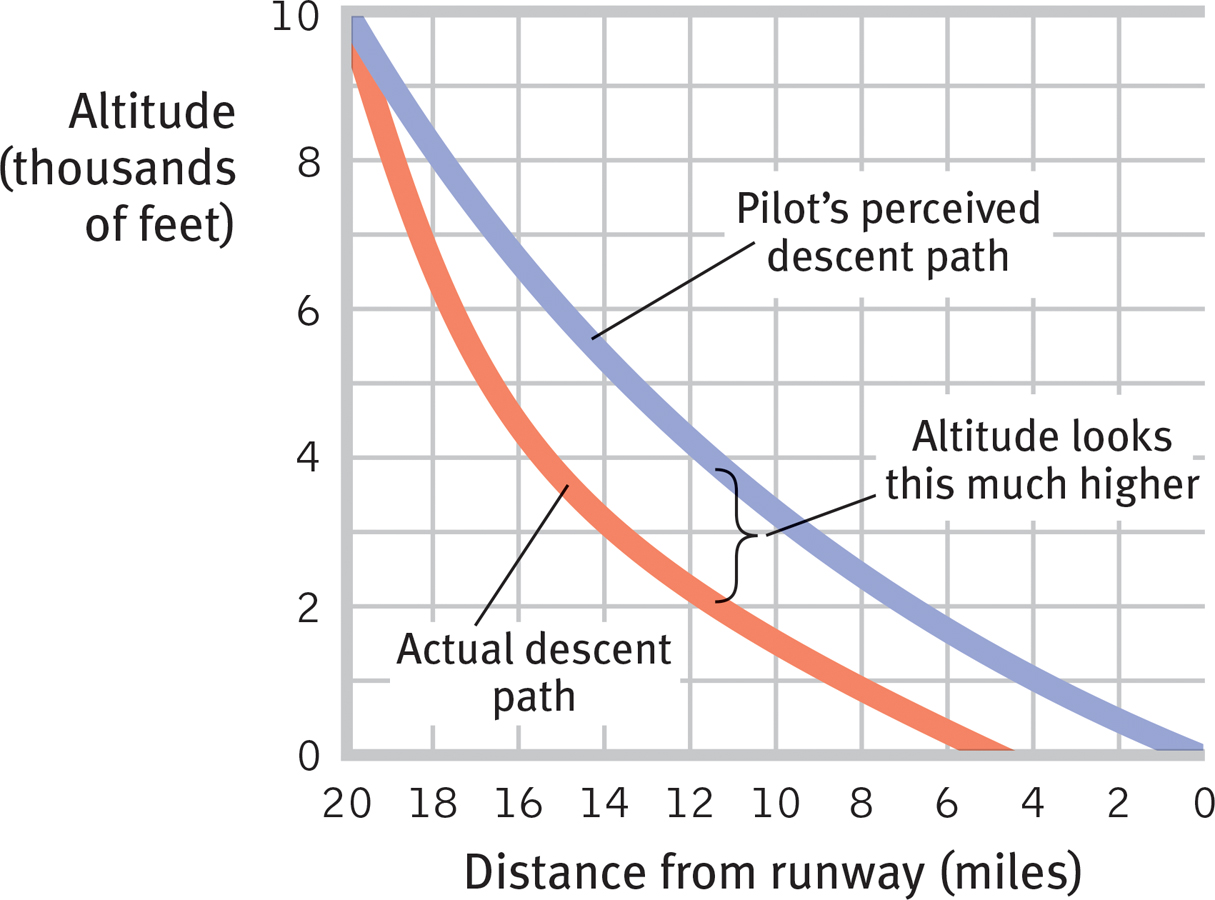

Understanding human factors can help prevent accidents. By studying the human factor in driving accidents, psychologists seek to devise ways to reduce the distractions, fatigue, and inattention that contribute to 1.3 million annual worldwide traffic fatalities (Lee, 2008). Two-thirds of commercial air accidents have been caused by human error (Nickerson, 1998). After beginning commercial flights in the 1960s, the Boeing 727 was involved in several landing accidents caused by pilot error. Psychologist Conrad Kraft (1978) noted a common setting for these accidents: All took place at night, and all involved landing short of the runway after crossing a dark stretch of water or unilluminated ground. Kraft reasoned that, on rising terrain, city lights beyond the runway would project a larger retinal image, making the ground seem farther away than it was. By re-creating these conditions in flight simulations, Kraft discovered that pilots were deceived into thinking they were flying higher than their actual altitudes (FIGURE A.5). Aided by Kraft’s finding, the airlines began requiring the co-pilot to monitor the altimeter—calling out altitudes during the descent—and the accidents diminished.

Figure A.5

Figure A.5

The human factor in accidents Lacking distance cues when approaching a runway from over a dark surface, pilots simulating a night landing tended to fly too low. (Data from Kraft, 1978.)

Later Boeing psychologists worked on other human factors problems (Murray, 1998): How should airlines best train and manage mechanics to reduce the maintenance errors that underlie about 50 percent of flight delays and 15 percent of accidents? What illumination and typeface would make on-screen flight data easiest to read? How could warning messages be most effectively worded—as an action statement (“Pull Up”) rather than a problem statement (“Ground Proximity”)?

Consider, finally, the available assistive listening technologies in various theaters, auditoriums, and places of worship. One technology, commonly available in the United States, requires a headset attached to a pocket-sized receiver that detects infrared or FM signals from the room’s sound system. The well-meaning people who design, purchase, and install these systems correctly understand that the technology puts sound directly into the user’s ears. Alas, few people with hearing loss undergo the hassle and embarrassment of locating, requesting, wearing, and returning a conspicuous headset. Most such units therefore sit in closets. Britain, the Scandinavian countries, and Australia, and now parts of the United States, have instead installed loop systems (see www.hearingloop.org) that broadcast customized sound directly through a person’s own hearing aid. When suitably equipped, a hearing aid can be transformed by a discrete touch of a switch into an in-the-ear loudspeaker. Offered convenient, inconspicuous, personalized sound, many more people elect to use assistive listening.

Designs that enable safe, easy, and effective interactions between people and technology often seem obvious after the fact. Why, then, aren’t they more common? Technology developers sometimes mistakenly assume that others share their expertise—that what’s clear to them will similarly be clear to others (Camerer et al., 1989; Nickerson, 1999). When people rap their knuckles on a table to convey a familiar tune (try this with a friend), they often expect their listener to recognize it. But for the listener, this is a near-impossible task (Newton, 1991). When you know a thing, it’s hard to mentally simulate what it’s like not to know, and that is called the curse of knowledge.

The point to remember: Everyone benefits when designers and engineers tailor machines and environments to fit human abilities and behaviors, when they user-test their inventions before production and distribution, and when they remain mindful of the curse of knowledge.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are the three main divisions within industrial-organizational psychology?

personnel, organizational, human factors

The human factor in safe landings Advanced cockpit design and rehearsed emergency procedures aided pilot Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger, a U.S. Air Force Academy graduate who studied psychology and human factors. In January 2009, Sullenberger’s instantaneous decisions safely guided his disabled airplane onto New York City’s Hudson River, where all 155 of the passengers and crew were safely evacuated.

The Human Factor

The Human Factor

Figure A.4

Figure A.4

Figure A.5

Figure A.5