23.2 Cognition's Influence on Conditioning

23-

Please continue to the next section.

Cognitive Processes and Classical Conditioning

In their dismissal of “mentalistic” concepts such as consciousness, Pavlov and Watson underestimated the importance of not only biological constraints, but also the effects of cognitive processes (thoughts, perceptions, expectations). Through cognitive learning we acquire mental information that guides our behavior. The early behaviorists believed that rats’ and dogs’ learned behaviors could be reduced to mindless mechanisms, so there was no need to consider cognition. But Robert Rescorla and Allan Wagner (1972) showed that an animal can learn the predictability of an event. If a shock always is preceded by a tone, and then may also be preceded by a light that accompanies the tone, a rat will react with fear to the tone but not to the light. Although the light is always followed by the shock, it adds no new information; the tone is a better predictor. The more predictable the association, the stronger the conditioned response. It’s as if the animal learns an expectancy, an awareness of how likely it is that the US will occur.

For more information on animal behavior, see books by (we are not making this up) Robin Fox and Lionel Tiger.

Associations can influence attitudes (Hofmann et al., 2010). When British children viewed novel cartoon characters alongside either ice cream (Yum!) or brussels sprouts (Yuk!), they came to like best the ice-

“All brains are, in essence, anticipation machines.”

Daniel C. Dennett, Consciousness Explained, 1991

Follow-

Such experiments help explain why classical conditioning treatments that ignore cognition often have limited success. For example, people receiving therapy for alcohol use disorder may be given alcohol spiked with a nauseating drug. Will they then associate alcohol with sickness? If classical conditioning were merely a matter of “stamping in” stimulus associations, we might hope so, and to some extent this does occur. However, one’s awareness that the nausea is induced by the drug, not the alcohol, often weakens the association between drinking alcohol and feeling sick. So, even in classical conditioning, it is—

Cognitive Processes and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner acknowledged the biological underpinnings of behavior and the existence of private thought processes. Nevertheless, many psychologists criticized him for discounting cognition’s importance.

A mere eight days before dying of leukemia in 1990, Skinner stood before the American Psychological Association convention. In this final address, he again resisted the growing belief that cognitive processes (thoughts, perceptions, expectations) have a necessary place in the science of psychology and even in our understanding of conditioning. He viewed “cognitive science” as a throwback to early twentieth-

305

Nevertheless, the evidence of cognitive processes cannot be ignored. For example, animals on a fixed-

Evidence of cognitive processes has also come from studying rats in mazes. Rats exploring a maze, given no obvious rewards, seem to develop a cognitive map, a mental representation of the maze. When an experimenter then places food in the maze’s goal box, these rats run the maze as quickly and efficiently as other rats that were previously reinforced with food for this result. Like people sightseeing in a new town, the exploring rats seemingly experienced latent learning during their earlier tours. That learning became apparent only when there was some incentive to demonstrate it. Children, too, may learn from watching a parent but demonstrate the learning only much later, as needed. The point to remember: There is more to learning than associating a response with a consequence; there is also cognition. We will encounter more striking evidence of animals’ cognitive abilities in solving problems and in using aspects of language.

The cognitive perspective has also shown us the limits of rewards: Promising people a reward for a task they already enjoy can backfire. Excessive rewards can destroy intrinsic motivation—the desire to perform a behavior effectively and for its own sake. In experiments, children have been promised a payoff for playing with an interesting puzzle or toy. Later, they played with the toy less than unpaid children (Deci et al., 1999; Tang & Hall, 1995). Likewise, rewarding children with toys or candy for reading diminishes the time they spend reading (Marinak & Gambrell, 2008). It is as if they think, “If I have to be bribed into doing this, it must not be worth doing for its own sake.”

To sense the difference between intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation (behaving in certain ways to gain external rewards or avoid threatened punishment), think about your experience in this course. Are you feeling pressured to finish this reading before a deadline? Worried about your grade? Eager for the credits that will count toward graduation? If Yes, then you are extrinsically motivated (as, to some extent, almost all students must be). Are you also finding the material interesting? Does learning it make you feel more competent? If there were no grade at stake, might you be curious enough to want to learn the material for its own sake? If Yes, intrinsic motivation also fuels your efforts.

Youth sports coaches who aim to promote enduring interest in an activity, not just to pressure players into winning, should focus on the intrinsic joys of playing and reaching one’s potential (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2009). Doing so may also ultimately lead to greater rewards. Students who focus on learning (intrinsic reward) often get good grades and graduate (extrinsic rewards). Doctors who focus on healing (intrinsic) may make a good living (extrinsic). Indeed, research suggests that people who focus on their work’s meaning and significance not only do better work but ultimately enjoy more extrinsic rewards (Wrzesniewski et al., 2014). Giving people choices also enhances their intrinsic motivation (Patall et al., 2008).

Nevertheless, extrinsic rewards used to signal a job well done (rather than to bribe or control someone) can be effective (Boggiano et al., 1985). “Most improved player” awards, for example, can boost feelings of competence and increase enjoyment of a sport. Rightly administered, rewards can improve performance and spark creativity (Eisenberger & Aselage, 2009; Henderlong & Lepper, 2002). And the rewards that often follow academic achievement, such as scholarships and jobs, are here to stay.

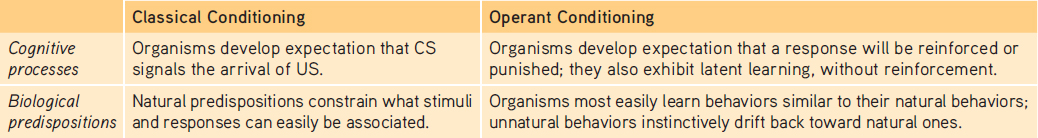

TABLE 23.1 compares the biological and cognitive influences on classical and operant conditioning.

Table 23.1

Table 23.1Biological and Cognitive Influences on Conditioning

306