28.5 Thinking and Language

28-

Thinking and language intricately intertwine. Asking which comes first is one of psychology’s chicken-

Language Influences Thinking

Linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf (1956) contended that “language itself shapes a [person’s] basic ideas.” The Hopi, who have no past tense for their verbs, could not readily think about the past, said Whorf.

Whorf’s linguistic determinism hypothesis is too extreme. We all think about things for which we have no words. (Can you think of a shade of blue you cannot name?) And we routinely have unsymbolized (wordless, imageless) thoughts, as when someone, while watching two men carry a load of bricks, wondered whether the men would drop them (Heavey & Hurlburt, 2008; Hurlburt et al., 2013).

Nevertheless, to those who speak two dissimilar languages, such as English and Japanese, it seems obvious that a person may think differently in different languages (Brown, 1986). Unlike English, which has a rich vocabulary for self-

380

Depending on which emotion they want to express, bilingual parents will often switch languages. “When my mom gets angry at me, she’ll speak in Mandarin,” explained one Chinese-

So our words may not determine what we think, but they do influence our thinking (Boroditsky, 2011). We use our language in forming categories. In Brazil, the isolated Piraha people have words for the numbers 1 and 2, but numbers above that are simply “many.” Thus, if shown 7 nuts in a row, they find it difficult to lay out the same number from their own pile (Gordon, 2004).

Words also influence our thinking about colors. Whether we live in New Mexico, New South Wales, or New Guinea, we see colors much the same, but we use our native language to classify and remember them (Davidoff, 2004; Roberson et al., 2004, 2005). Imagine viewing three colors and calling two of them “yellow” and one of them “blue.” Later you would likely see and recall the yellows as being more similar. But if you speak the language of Papua New Guinea’s Berinmo tribe, which has words for two different shades of yellow, you would more speedily perceive and better recall the variations between the two yellows. And if your language is Russian, which has distinct names for various shades of blue, such as goluboy and siniy, you might recall the yellows as more similar and remember the blues better. Words matter.

Perceived differences grow as we assign different names. On the color spectrum, blue blends into green—

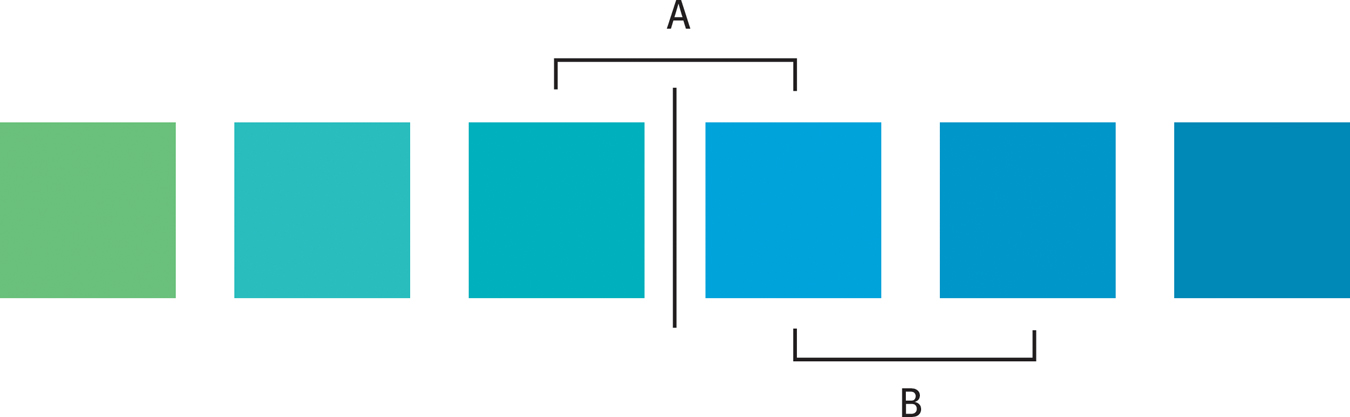

Figure 28.3

Figure 28.3Language and perception When people view blocks of equally different colors, they perceive those with different names as more different. Thus the “green” and “blue” in contrast A may appear to differ more than the two equally different blues in contrast B (Özgen, 2004).

Given words’ subtle influence on thinking, we do well to choose our words carefully. Is “A child learns language as he interacts with his caregivers” any different from “Children learn language as they interact with their caregivers”? Many studies have found that it is. When hearing the generic he (as in “the artist and his work”) people are more likely to picture a male (Henley, 1989; Ng, 1990). If he and his were truly gender free, we shouldn’t skip a beat when hearing that “man, like other mammals, nurses his young.”

To expand language is to expand the ability to think. Children’s thinking develops hand in hand with their language (Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1986). Indeed, it is very difficult to think about or conceptualize certain abstract ideas (commitment, freedom, or rhyming) without language! And what is true for preschoolers is true for everyone: It pays to increase your word power. That’s why most textbooks, including this one, introduce new words—

381

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.”

Henry Ward Beecher, Proverbs from Plymouth Pulpit, 1887

Increased word power helps explain what McGill University researcher Wallace Lambert (1992; Lambert et al., 1993) has called the bilingual advantage. Bilingual people are skilled at inhibiting one language while using the other. And thanks to their well-

To consider how researchers have learned about the benefits of learning more than one language, visit LaunchPad’s How Would You Know If There is a Bilingual Advantage?

Lambert helped devise a Canadian program that immerses English-

Whether we are in the linguistic minority or majority, language links us to one another. Language also connects us to the past and the future. “To destroy a people, destroy their language,” observed poet Joy Harjo.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Benjamin Lee Whorf’s controversial hypothesis, called _____________ _____________, suggested that we cannot think about things unless we have words for those concepts or ideas.

linguistic determinism

Thinking in Images

When you are alone, do you talk to yourself? Is “thinking” simply conversing with yourself? Without a doubt, words convey ideas. But sometimes ideas precede words. To turn on the cold water in your bathroom, in which direction do you turn the handle? To answer, you probably thought not in words but with implicit (nondeclarative, procedural) memory—

“When we see a person walking down the street talking to himself, we generally assume that he is mentally ill. But we all talk to ourselves continuously—we just have the good sense of keeping our mouths shut…. It’s as though we are having a conversation with an imaginary friend possessed of infinite patience. Who are we talking to?”

Sam Harris, “We Are Lost in Thought,” 2011

Indeed, we often think in images. Artists think in images. So do composers, poets, mathematicians, athletes, and scientists. Albert Einstein reported that he achieved some of his greatest insights through visual images and later put them into words. Pianist Liu Chi Kung harnessed the power of thinking in images. One year after placing second in the 1958 Tschaikovsky piano competition, Liu was imprisoned during China’s cultural revolution. Soon after his release, after seven years without touching a piano, he was back on tour. Critics judged Liu’s musicianship as better than ever. How did he continue to develop without practice? “I did practice,” said Liu, “every day. I rehearsed every piece I had ever played, note by note, in my mind” (Garfield, 1986).

For someone who has learned a skill, such as ballet dancing, even watching the activity will activate the brain’s internal simulation of it, reported one British research team after collecting fMRIs as people watched videos (Calvo-

One experiment on mental practice and basketball free-

382

Mental rehearsal can also help you achieve an academic goal, as researchers demonstrated with two groups of introductory psychology students facing a midterm exam one week later (Taylor et al., 1998). (Scores of other students, not engaging in any mental simulation, formed a control group.) The first group spent five minutes each day visualizing themselves scanning the posted grade list, seeing their A, beaming with joy, and feeling proud. This outcome simulation had little effect, adding only 2 points to their exam-

To experience your own thinking as (a) manipulating words and (b) manipulating images, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: My Head Is Spinning!

To experience your own thinking as (a) manipulating words and (b) manipulating images, visit LaunchPad’s PsychSim 6: My Head Is Spinning!

***

What, then, should we say about the relationship between thinking and language? As we have seen, language influences our thinking. But if thinking did not also affect language, there would never be any new words. And new words and new combinations of old words express new ideas. The basketball term slam dunk was coined after the act itself had become fairly common. Blogs became part of our language after web logs appeared. So, let us say that thinking affects our language, which then affects our thought (FIGURE 28.4).

Figure 28.4

Figure 28.4The interplay of thought and language The traffic runs both ways between thinking and language. Thinking affects our language, which affects our thought.

Psychological research on thinking and language mirrors the mixed impressions of our species by those in fields such as literature and religion. The human mind is simultaneously capable of striking intellectual failures and of striking intellectual power. Misjudgments are common and can have disastrous consequences. So we do well to appreciate our capacity for error. Yet our efficient heuristics—

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What is mental practice, and how can it help you to prepare for an upcoming event?

Mental practice uses visual imagery to mentally rehearse future behaviors, activating some of the same brain areas used during the actual behaviors. Visualizing the details of the process is more effective than visualizing only your end goal.

383