33.1 Instincts and Evolutionary Psychology

Early in the twentieth century, as Charles Darwin’s influence grew, it became fashionable to classify all sorts of behaviors as instincts. If people criticized themselves, it was because of their “self-abasement instinct.” If they boasted, it reflected their “self-assertion instinct.” After scanning 500 books, one sociologist compiled a list of 5759 supposed human instincts! Before long, this instinct-naming fad collapsed under its own weight. Rather than explaining human behaviors, the early instinct theorists were simply naming them. It was like “explaining” a bright child’s low grades by labeling the child an “underachiever.” To name a behavior is not to explain it.

To qualify as an instinct, a complex behavior must have a fixed pattern throughout a species and be unlearned (Tinbergen, 1951). Such behaviors are common in other species (think of imprinting in birds and the return of salmon to their birthplace). Some human behaviors, such as infants’ innate reflexes for rooting and sucking, also exhibit unlearned fixed patterns, but many more are directed by both physiological needs and psychological wants.

Instinct theory failed to explain most human motives, but its underlying assumption continues in evolutionary psychology: Genes do predispose some species-typical behavior. Psychologists might apply this perspective, for example, to explain our human similarities, animals’ biological predispositions, and the influence of evolution on our phobias, our helping behaviors, and our romantic attractions.

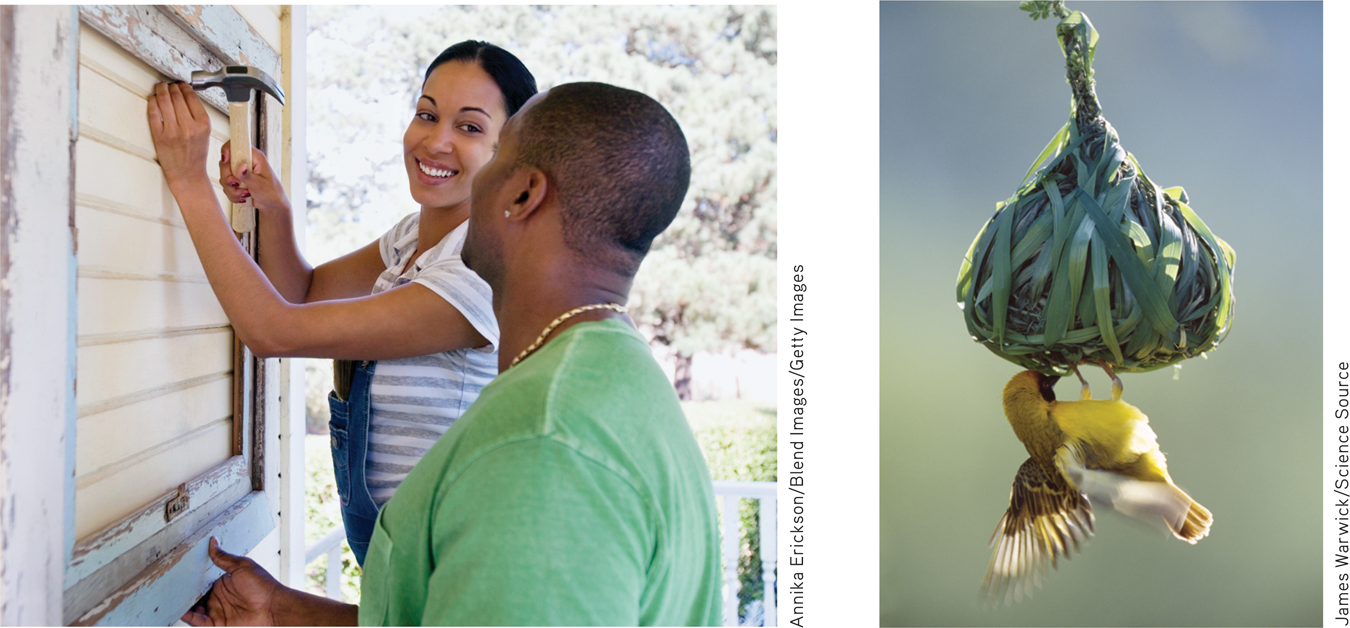

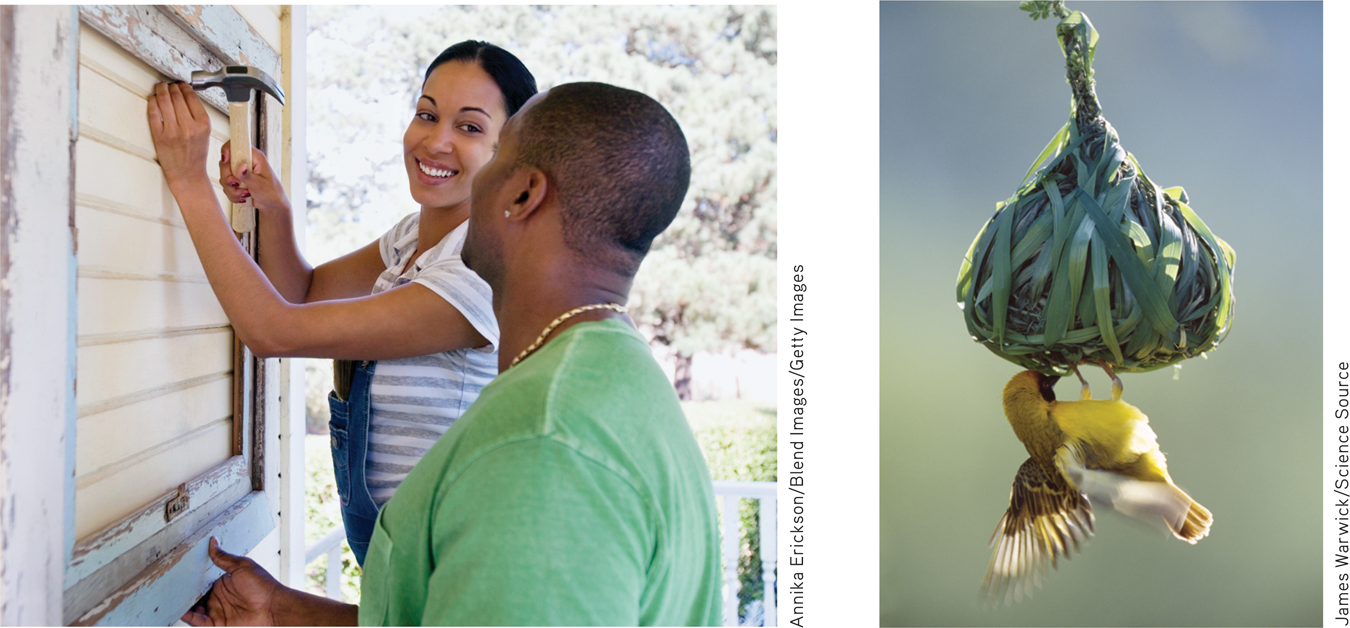

Same motive, different wiring The more complex the nervous system, the more adaptable the organism. Both humans and weaverbirds satisfy their need for shelter in ways that reflect their inherited capacities. Human behavior is flexible; we can learn whatever skills we need to build a house. The bird’s behavior pattern is fixed; it can build only this kind of nest.