33.2 Drives and Incentives

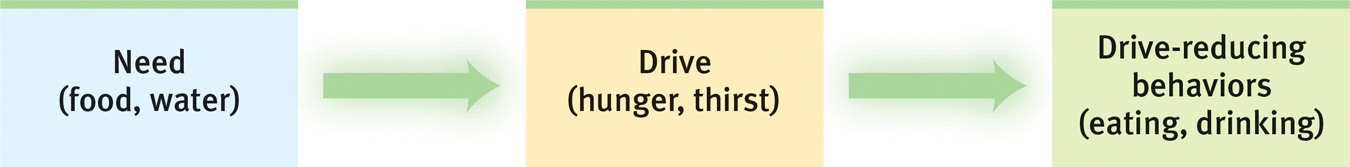

When the original instinct theory of motivation collapsed, it was replaced by drive-reduction theory—the idea that a physiological need (such as for food or water) creates an aroused state that drives the organism to reduce the need. With few exceptions, when a physiological need increases, so does a psychological drive—an aroused, motivated state.

The physiological aim of drive reduction is homeostasis—the maintenance of a steady internal state. An example of homeostasis (literally “staying the same”) is the body’s temperature-

Figure 33.1

Figure 33.1Drive-

Not only are we pushed by our need to reduce drives, we also are pulled by incentives—positive or negative environmental stimuli that lure or repel us. This is one way our individual learning histories influence our motives. Depending on our learning, the aroma of good food, whether fresh roasted peanuts or toasted ants, can motivate our behavior. So can the sight of those we find attractive or threatening.

When there is both a need and an incentive, we feel strongly driven. The food-