38.2 Gender, Emotion, and Nonverbal Behavior

38-2 Do the genders differ in their ability to communicate nonverbally?

Is women’s intuition, as so many believe, superior to men’s? After analyzing 125 studies of sensitivity to nonverbal cues, Judith Hall (1984, 1987) concluded that women generally do surpass men at reading people’s emotional cues when given thin slices of behavior. The female advantage emerges early in development. In one analysis of 107 study findings, female infants, children, and adolescents outperformed males (McClure, 2000).

Women’s nonverbal sensitivity helps explain their greater emotional literacy. When invited to describe how they would feel in certain situations, men described simpler emotional reactions (Barrett et al., 2000). You might like to try this yourself: Ask some people how they might feel when saying good-bye to friends after graduation. Research suggests men are more likely to say, simply, “I’ll feel bad,” and women to express more complex emotions: “It will be bittersweet; I’ll feel both happy and sad.”

Women’s skill at decoding others’ emotions may also contribute to their greater emotional responsiveness (Vigil, 2009). In studies of 23,000 people from 26 cultures, women more than men reported themselves open to feelings (Costa et al., 2001). Children show the same gender difference: Girls express stronger emotions than boys do (Chaplin & Aldao, 2013). That helps explain the extremely strong perception that emotionality is “more true of women”—a perception expressed by nearly 100 percent of 18-to 29-year-old Americans (Newport, 2001).

One exception: Quickly—imagine an angry face. What gender is the person? If you’re like 3 in 4 Arizona State University students, you imagined a male (Becker et al., 2007). And when a gender-neutral face was made to look angry, most people perceived it as male. If the face was smiling, they were more likely to perceive it as female (FIGURE 38.2). Anger strikes most people as a more masculine emotion.

Figure 38.2

Figure 38.2

Male or female? Researchers manipulated a gender-neutral face. People were more likely to see it as a male when it wore an angry expression, and as a female when it wore a smile (Becker et al., 2007).

The perception of women’s emotionality also feeds—and is fed by—people’s attributing women’s emotionality to their disposition and men’s to their circumstances: “She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day” (Barrett & Bliss-Moreau, 2009). Many factors influence our attributions, including cultural norms (Mason & Morris, 2010). Nevertheless, there are some gender differences in descriptions of emotional experiences. When surveyed, women are also far more likely than men to describe themselves as empathic. If you have empathy, you identify with others and imagine what it must be like to walk in their shoes. You rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep. Fiction readers, who immerse themselves in the lives of their favorite characters, report higher empathy levels (Mar et al., 2009). This may help explain why, compared with men, women read more fiction (Tepper, 2000). Physiological measures, such as heart rate while seeing another’s distress, confirm the empathic gender gap, though a smaller one than indicated in survey self-reports (Eisenberg & Lennon, 1983; Rueckert et al., 2010).

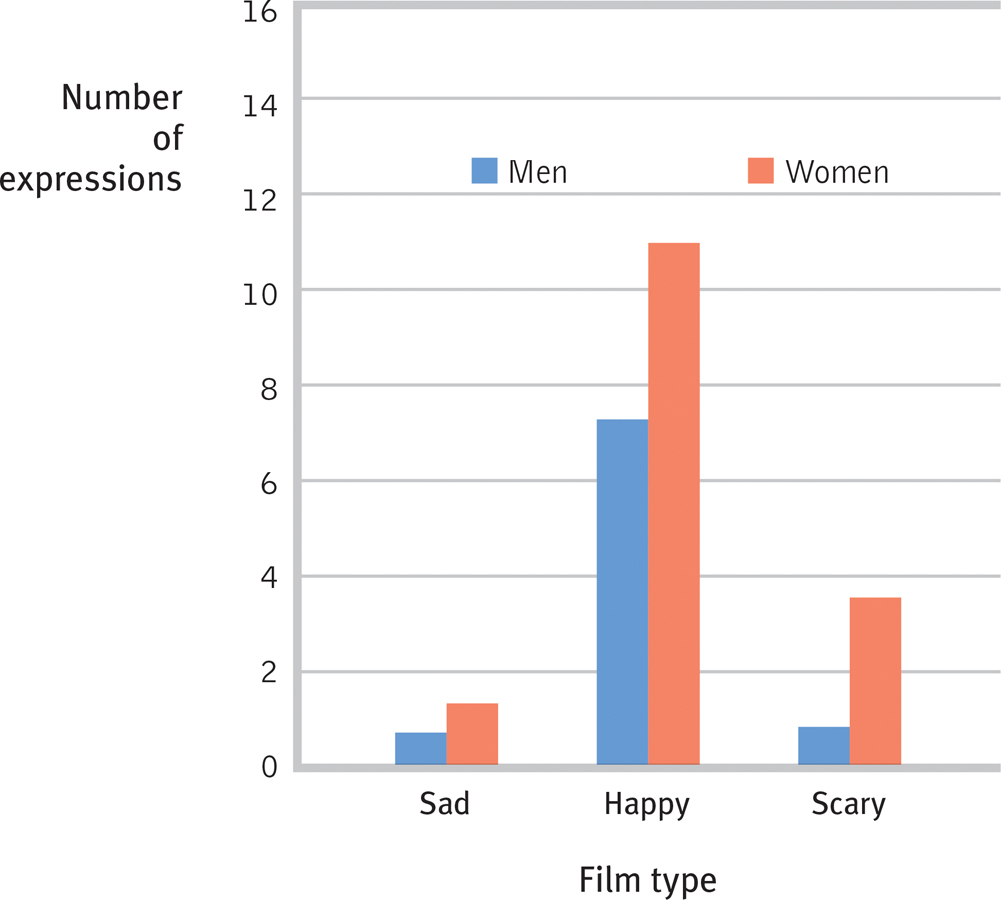

Females are also more likely to express empathy—to cry and to report distress when observing someone in distress. As FIGURE 38.3 shows, this gender difference was clear in videotapes of male and female students watching film clips that were sad (children with a dying parent), happy (slapstick comedy), or frightening (a man nearly falling off the ledge of a tall building) (Kring & Gordon, 1998). Women also tend to experience emotional events, such as viewing pictures of mutilation, more deeply and with more brain activation in areas sensitive to emotion. And they better remember the scenes three weeks later (Canli et al., 2002).

Figure 38.3

Figure 38.3

Gender and expressiveness Male and female film viewers did not differ dramatically in self-reported emotions or physiological responses. But the women’s faces showed much more emotion. (Data from Kring & Gordon, 1998.)

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- _____________ (Women/Men) report experiencing emotions more deeply, and they tend to be more adept at reading nonverbal behavior.

Women

Figure 38.2

Figure 38.2

Figure 38.3

Figure 38.3