38.3 Culture and Emotional Expression

38-

The meaning of gestures varies with the culture. U.S. President Richard Nixon learned this after making the North American “A-

472

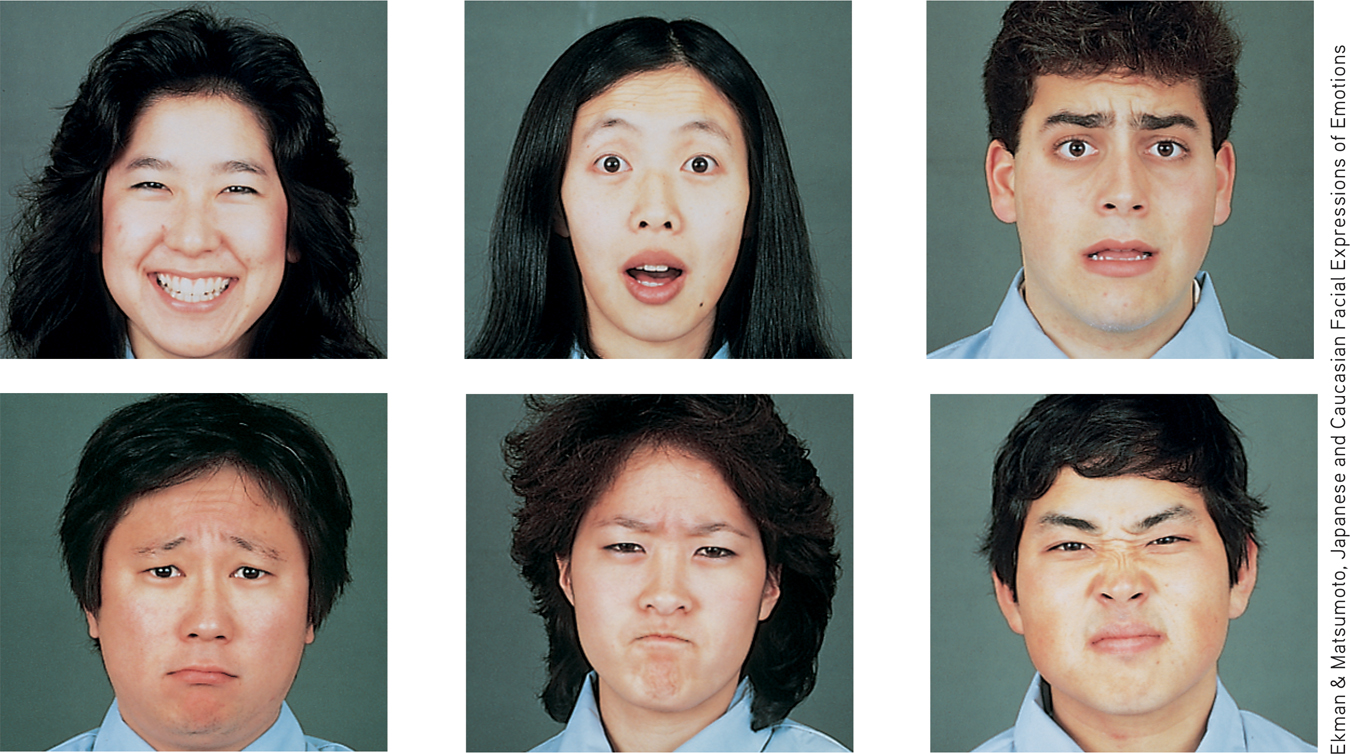

Do facial expressions also have different meanings in different cultures? To find out, two investigative teams showed photographs of various facial expressions to people in different parts of the world and asked them to guess the emotion (Ekman et al., 1975, 1987, 1994; Izard, 1977, 1994). You can try this matching task yourself by pairing the six emotions with the six faces in FIGURE 38.4.

Figure 38.4

Figure 38.4Culture-

Regardless of your cultural background, you probably did pretty well. A smile’s a smile the world around. Ditto for sadness, and to a lesser extent the other basic expressions (Jack et al., 2012). (There is no culture where people frown when they are happy.)

Facial expressions do convey some nonverbal accents that provide clues to one’s culture (Marsh et al., 2003). Thus, data from 182 studies have shown slightly enhanced accuracy when people judged emotions from their own culture (Elfenbein & Ambady, 2002, 2003a,b). Still, the telltale signs of emotion generally cross cultures. The world over, children cry when distressed, shake their heads when defiant, and smile when they are happy. So, too, with blind children who have never seen a face (Eibl-

Musical expressions of emotion also cross cultures. Happy and sad music feels happy and sad around the world. Whether you live in an African village or a European city, fast-

Do these shared emotional categories reflect shared cultural experiences, such as movies and TV broadcasts seen around the world? Apparently not. Paul Ekman and his team asked isolated people in New Guinea to respond to such statements as, “Pretend your child has died.” When North American collegians viewed the taped responses, they easily read the New Guineans’ facial reactions.

473

“For news of the heart, ask the face.”

Guinean proverb

So we can say that facial muscles speak a universal language. This discovery would not have surprised Charles Darwin (1809–

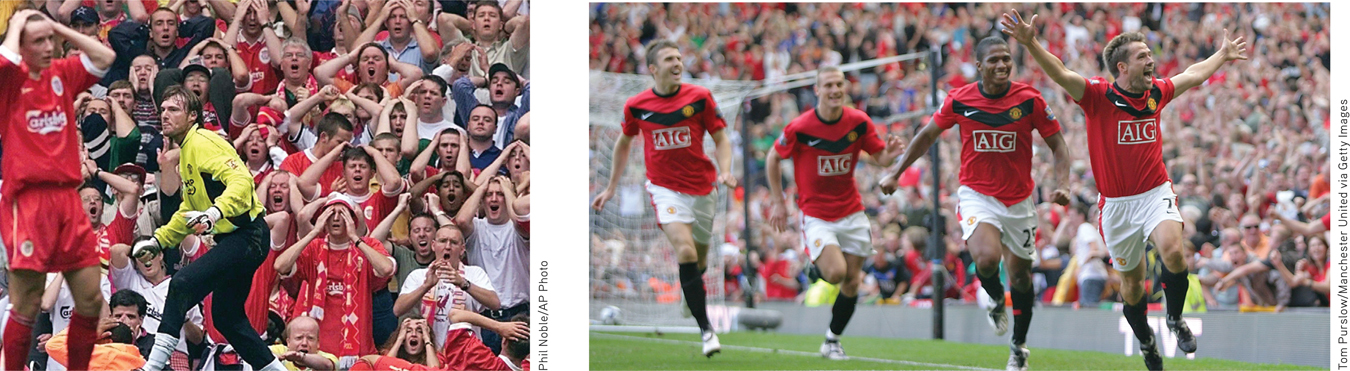

Smiles are social as well as emotional events. Euphoric Olympic gold-

For a 4-minute demonstration of our universal facial language, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotions and Facial Expression.

For a 4-minute demonstration of our universal facial language, visit LaunchPad’s Video: Emotions and Facial Expression.

Although we share a universal facial language, it has been adaptive for us to interpret faces in particular contexts (FIGURE 38.5). People judge an angry face set in a frightening situation as afraid. They judge a fearful face set in a painful situation as pained (Carroll & Russell, 1996). Movie directors harness this phenomenon by creating contexts and soundtracks that amplify our perceptions of particular emotions.

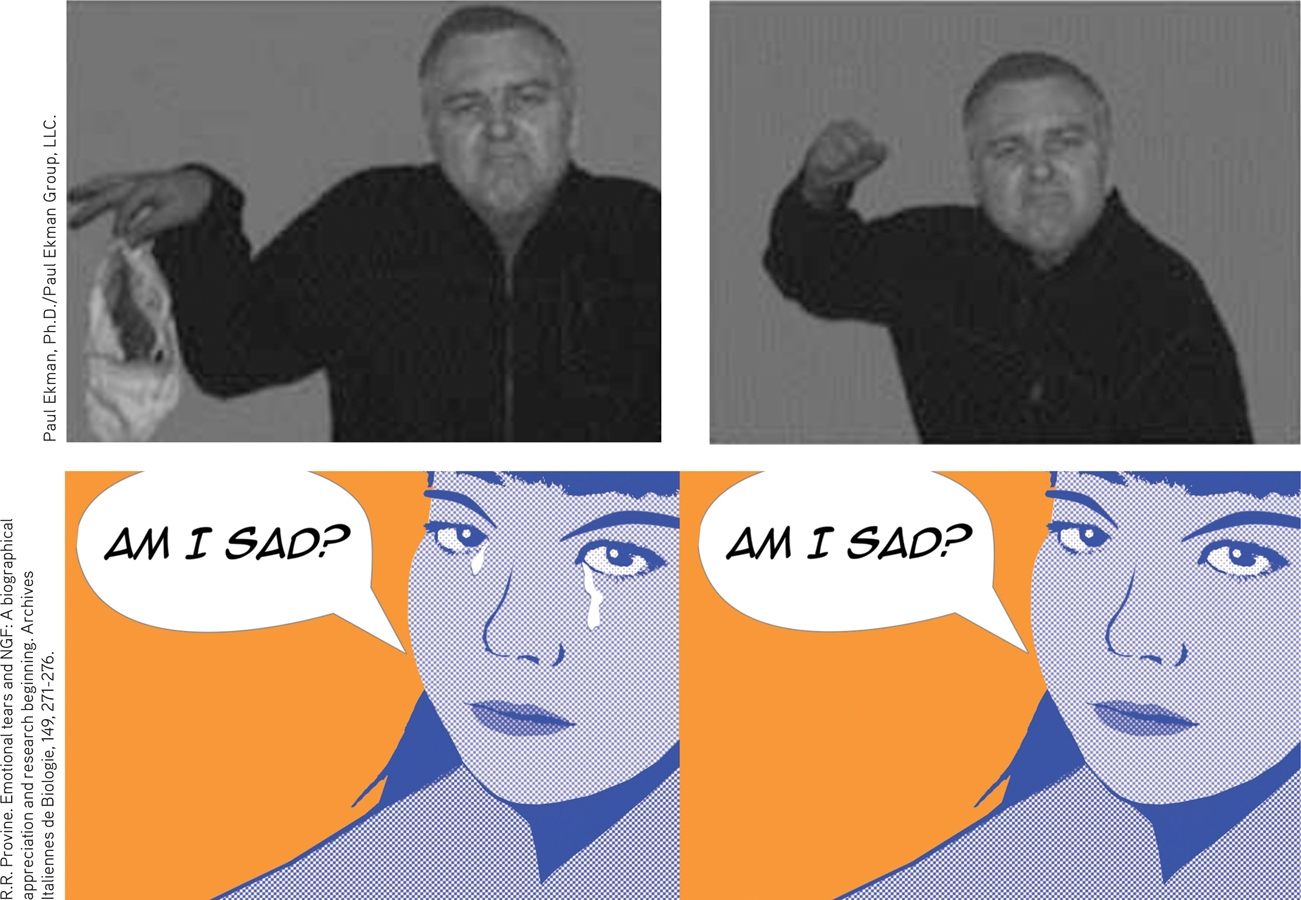

Figure 38.5

Figure 38.5We read faces in context Whether we perceive the man in the top row as disgusted or angry depends on which body his face appears on (Aviezer et al., 2008). In the second row, tears on a face make its expression seem sadder (Provine et al., 2009).

While weightless, astronauts’ internal bodily fluids move toward their upper body and their faces become puffy. This makes nonverbal communication more difficult, especially among multinational crews (Gelman, 1989).

Although cultures share a universal facial language for some basic emotions, they differ in how much emotion they express. Those that encourage individuality, as in Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, and North America, display mostly visible emotions (van Hemert et al., 2007). Those that encourage people to adjust to others, as in China, tend to have less visible displays of personal emotions (Matsumoto et al., 2009b; Tsai et al., 2007). In Japan, people infer emotion more from the surrounding context. Moreover, the mouth, which is so expressive in North Americans, conveys less emotion than do the telltale eyes (Masuda et al., 2008; Yuki et al., 2007).

474

Cultural differences also exist within nations. The Irish and their Irish-

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Are people in different cultures more likely to differ in their interpretations of facial expressions or of gestures?

gestures