40.2 Stress and Vulnerability to Disease

40-

To study how stress, and healthy and unhealthy behaviors influence health and illness, psychologists and physicians have created the interdisciplinary field of behavioral medicine, integrating behavioral and medical knowledge. Health psychology provides psychology’s contribution to behavioral medicine. The subfield of psychoneuroimmunology, focuses on mind-

493

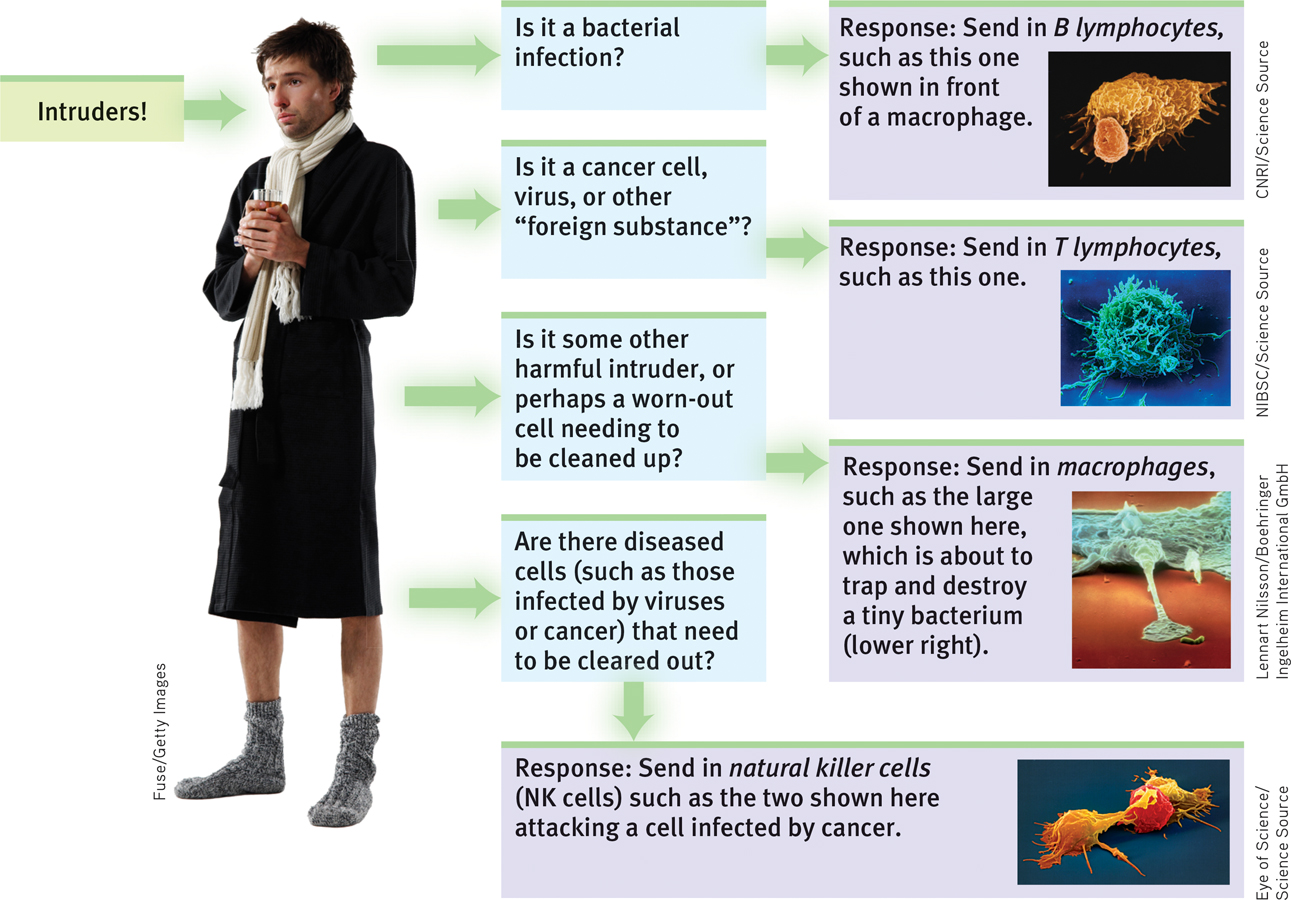

If you’ve ever had a stress headache, or felt your blood pressure rise with anger, you don’t need to be convinced that our psychological states have physiological effects. Stress can even leave you less able to fight off disease because your nervous and endocrine systems influence your immune system (Sternberg, 2009). You can think of the immune system as a complex surveillance system. When it functions properly, it keeps you healthy by isolating and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other invaders. Four types of cells are active in these search-

Figure 40.4

Figure 40.4A simplified view of immune responses

- B lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the bone marrow and release antibodies that fight bacterial infections.

- T lymphocytes (white blood cells) mature in the thymus and other lymphatic tissue and attack cancer cells, viruses, and foreign substances.

- Macrophages (“big eaters”) identify, pursue, and ingest harmful invaders and worn-out cells.

- Natural killer cells (NK cells) pursue diseased cells (such as those infected by viruses or cancer).

Your age, nutrition, genetics, body temperature, and stress all influence your immune system’s activity. When your immune system doesn’t function properly, it can err in two directions:

- Responding too strongly, it may attack the body’s own tissues, causing an allergic reaction or a self-attacking disease, such as lupus, multiple sclerosis, or some forms of arthritis. Women, who are immunologically stronger than men, are more susceptible to self-attacking diseases (Nussinovitch & Schoenfeld, 2012; Schwartzman-Morris & Putterman, 2012).

- Underreacting, the immune system may allow a bacterial infection to flare, a dormant virus to erupt, or cancer cells to multiply. To protect transplanted organs, which the recipient’s system would view as a foreign body, surgeons may deliberately suppress the patient’s immune system.

494

Stress can also trigger immune suppression by reducing the release of disease-

Human immune systems react similarly. Some examples:

- Surgical wounds heal more slowly in stressed people. In one experiment, dental students received punch wounds (precise small holes punched in the skin). Compared with wounds placed during summer vacation, those placed three days before a major exam healed 40 percent more slowly (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 1998). In other studies, marriage conflict has also slowed punch-wound healing (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2005).

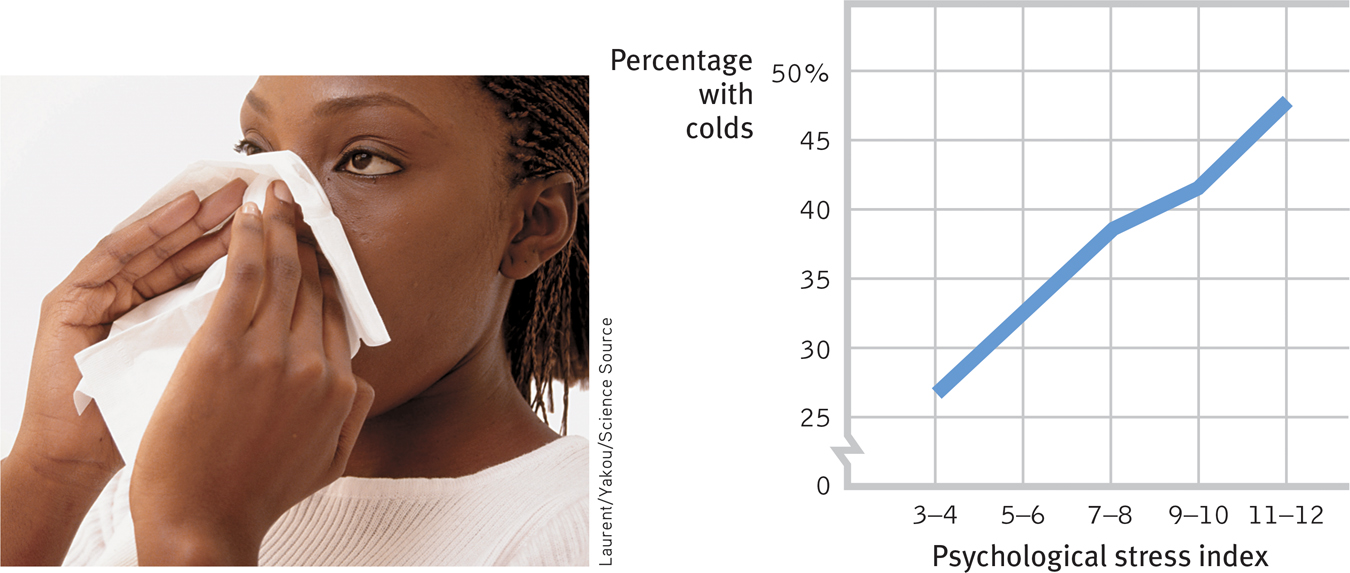

- Stressed people are more vulnerable to colds. Major life stress increases the risk of a respiratory infection (Pedersen et al., 2010). When researchers dropped a cold virus into the noses of stressed and relatively unstressed people, 47 percent of those living stress-filled lives developed colds (FIGURE 40.5). Among those living relatively free of stress, only 27 percent did. In follow-

up research, the happiest and most relaxed people were likewise markedly less vulnerable to an experimentally delivered cold virus (Cohen et al., 2003; Cohen & Pressman, 2006).

Figure 40.5

Figure 40.5

Stress and colds In an experiment by Sheldon Cohen and colleagues (1991), people with the highest life stress scores were also most vulnerable when exposed to an experimentally delivered cold virus. (Data from Cohen et al., 1991.) - Low stress may increase the effectiveness of vaccinations. Nurses gave older adults a flu vaccine and then measured how well their bodies fought off bacteria and viruses. The vaccine was most effective among older adults who experienced low stress (Segerstrom et al., 2012).

The stress effect on immunity makes physiological sense. It takes energy to track down invaders, produce swelling, and maintain fevers. Thus, when diseased, your body reduces its muscular energy output by decreasing activity and increasing sleep. Stress does the opposite. It creates a competing energy need. During an aroused fight-

495

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The field of ______________ studies mind-body interactions, including the effects of psychological, neural, and endocrine functioning on the immune system and overall health.

psychoneuroimmunology

- What general effect does stress have on our overall health?

Stress tends to reduce our immune system’s ability to function properly, so that higher stress generally leads to greater incidence of physical illness.

Stress and AIDS

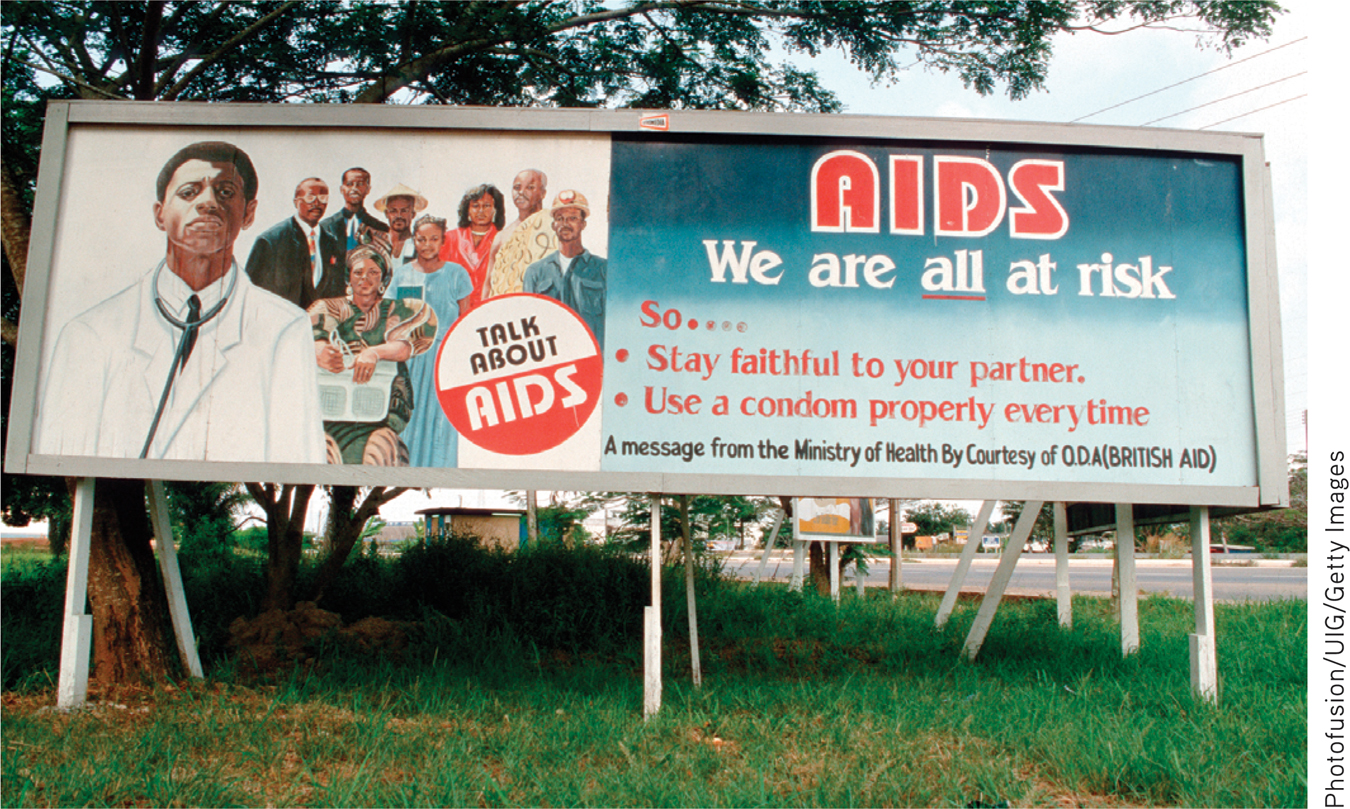

We know that stress suppresses immune system functioning. What does this mean for people with AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome)? As its name tells us, AIDS is an immune disorder, caused by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although AIDS-

Ironically, if a disease is spread by human contact (as AIDS is, through the exchange of bodily fluids, primarily semen and blood), and if it kills slowly (as AIDS does), it can be lethal to more people. Those who acquire HIV often spread it in the highly contagious first few weeks before they know they are infected. Worldwide, some 2.3 million people—

Stress cannot give people AIDS. But could stress and negative emotions speed the transition from HIV infection to AIDS? And might stress predict a faster decline in those with AIDS? An analysis of 33,252 participants from around the world suggest the answer to both questions is Yes (Chida & Vedhata, 2009). The greater the stress that HIV-

Would efforts to reduce stress help control the disease? Again, the answer appears to be Yes. Educational initiatives, bereavement support groups, cognitive therapy, relaxation training, and exercise programs that reduce distress have all had positive consequences for HIV-

Although AIDS is now more treatable than ever before, preventing HIV infection is a far better option. This is the focus of many educational programs, such as the ABC (Abstinence, Be faithful, Condom use) program that has been used with seeming success in Uganda (Altman, 2004; UNAIDS, 2005). In addition to such programs that seek to influence sexual norms and behaviors, today’s combination prevention programs also include medical strategies (such as drugs and male circumcision that reduce HIV transmission) and efforts to reduce social inequalities that increase HIV risk (UNAIDS, 2010).

Stress and Cancer

Stress does not create cancer cells. But in a healthy, functioning immune system, lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells search out and destroy cancer cells and cancer-

496

Does this stress-

“I didn’t give myself cancer.”

Mayor Barbara Boggs Sigmund (1939–1990), Princeton, New Jersey

One danger in hyping reports on emotions and cancer is that some patients may then blame themselves for their illness: “If only I had been more expressive, relaxed, and hopeful.” A corollary danger is a “wellness macho” among the healthy, who take credit for their “healthy character” and lay a guilt trip on the ill: “She has cancer? That’s what you get for holding your feelings in and being so nice.” Dying thus becomes the ultimate failure.

When organic causes of illness are unknown, it is tempting to invent psychological explanations. Before the germ that causes tuberculosis was discovered, personality explanations of TB were popular (Sontag, 1978).

It’s important enough to repeat: Stress does not create cancer cells. At worst, it may affect their growth by weakening the body’s natural defenses against multiplying malignant cells (Antoni & Lutgendorf, 2007). Although a relaxed, hopeful state may enhance these defenses, we should be aware of the thin line that divides science from wishful thinking. The powerful biological processes at work in advanced cancer or AIDS are not likely to be completely derailed by avoiding stress or maintaining a relaxed but determined spirit (Anderson, 2002; Kessler et al., 1991). And that explains why research has consistently indicated that psychotherapy does not extend cancer patients’ survival (Coyne et al., 2007, 2009; Coyne & Tennen, 2010).

For a 7-minute demonstration of the links between stress, cancer, and the immune system, visit LaunchPad’s Video—Fighting Cancer: Mobilizing the Immune System.

For a 7-minute demonstration of the links between stress, cancer, and the immune system, visit LaunchPad’s Video—Fighting Cancer: Mobilizing the Immune System.

Stress and Heart Disease

40-

Depart from reality for a moment. In this new world, you wake up each day, eat your breakfast, and check the news. Political coverage buzzes, local events snap up airtime, and your favorite sports team occasionally wins. But there is a fourth story: Four 747 jumbo jet airlines crashed yesterday and all 1642 passengers died. You finish your breakfast, grab your books, and head to class. It’s just an average day.

Replace airline crashes with coronary heart disease, the United States’ leading cause of death, and you have re-

Stress and personality also play a big role in heart disease. The more psychological trauma people experience, the more their bodies generate inflammation, which is associated with heart and other health problems (O’Donovan et al., 2012). Plucking a hair and measuring its level of cortisol (a stress hormone) can help predict whether a person will have a future heart attack (Pereg et al., 2011).

497

Type A PersonalityIn a now-

In both India and America, Type A bus drivers are literally hard-driving: They brake, pass, and honk their horns more often than their more easygoing Type B colleagues (Evans et a l., 1987).

So, are some of us at high risk of stress-

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.”

Chinese proverb

Nine years later, 257 men had suffered heart attacks, and 69 percent of them were Type A. Moreover, not one of the “pure” Type Bs—

As often happens in science, this exciting discovery provoked enormous public interest. After that initial honeymoon period, researchers wanted to know more. Was the finding reliable? If so, what was the toxic component of the Type A profile: Time-

More than 700 studies have now explored possible psychological correlates or predictors of cardiovascular health (Chida & Hamer, 2008; Chida & Steptoe, 2009). These reveal that Type A’s toxic core is negative emotions—

Hundreds of other studies of young and middle-

498

Type D PersonalityIn recent years, another personality type has interested stress and heart disease researchers. Type A individuals direct their negative emotion toward dominating others. People with another personality type—

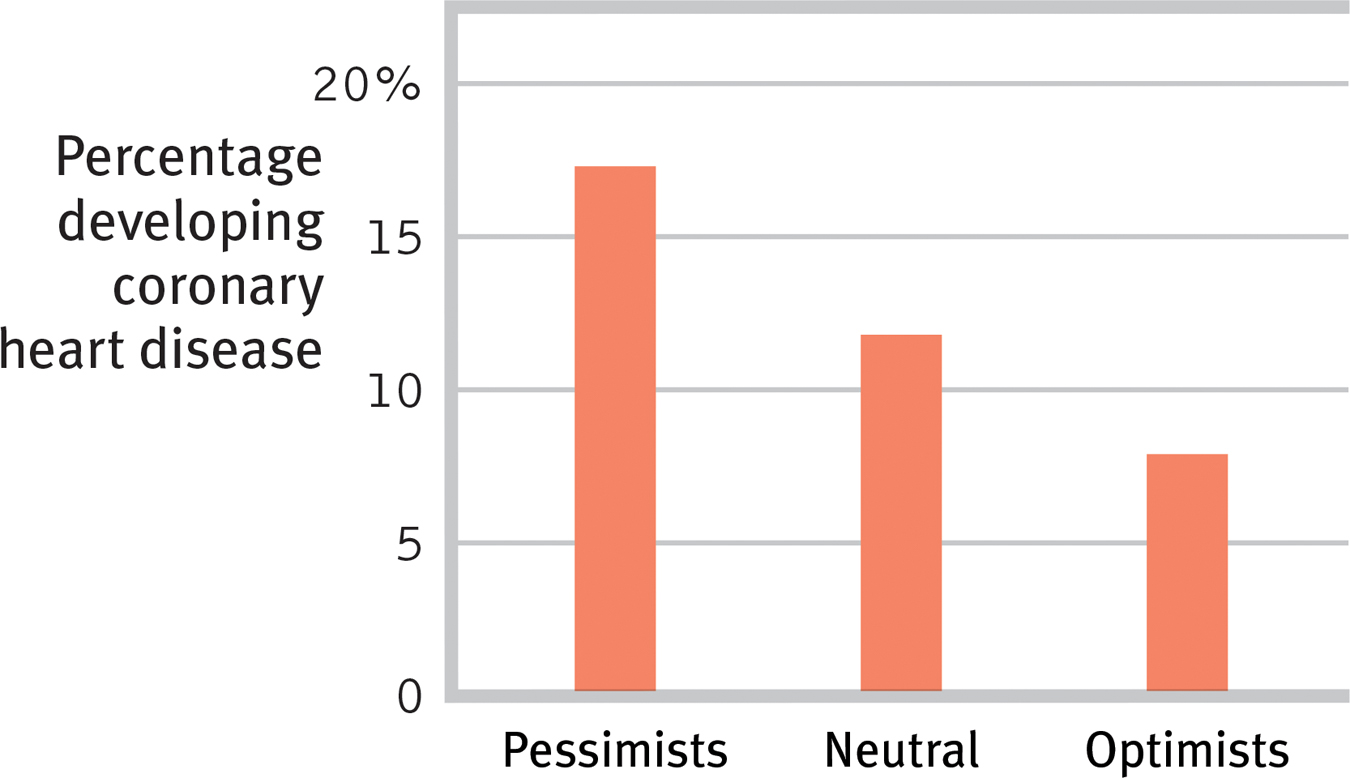

Effects of Pessimism and DepressionPessimism seems to be similarly toxic. Laura Kubzansky and her colleagues (2001) studied 1306 initially healthy men who a decade earlier had scored as optimists, pessimists, or neither. Even after other risk factors such as smoking had been ruled out, pessimists were more than twice as likely as optimists to develop heart disease (FIGURE 40.6).

Figure 40.6

Figure 40.6Pessimism and heart disease A Harvard School of Public Health team found pessimistic men at doubled risk of developing heart disease over a 10-

“A cheerful heart is a good medicine, but a downcast spirit dries up the bones.”

Proverbs 17:22

Depression, too, can be lethal. Happy people tend to be healthier and to outlive their unhappy peers (Diener & Chan, 2011; Siahpush et al., 2008). Even a big, happy smile predicts longevity, as researchers discovered when they examined the photographs of 150 Major League Baseball players who had appeared in the 1952 Baseball Register and had died by 2009 (Abel & Kruger, 2010). On average, the nonsmilers had died at 73, compared with an average 80 years for those with a broad, genuine smile. People with broad smiles tend to have extensive social networks, which predict longer life (Hertenstein, 2009).

To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit Launch-Pad’s How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

The accumulated evidence suggests that “depression substantially increases the risk of death, especially death by unnatural causes and cardiovascular disease” (Wulsin et al., 1999). After following 63,469 women over a dozen years, researchers found more than a doubled rate of heart attack death among those who initially scored as depressed (Whang et al., 2009). In the years following a heart attack, people with high scores for depression were four times more likely than their low-

Stress and InflammationDepressed people tend to smoke more and exercise less (Whooley et al., 2008), but stress itself is also disheartening:

- When following 17,415 middle-aged American women, researchers found an 88 percent increased risk of heart attacks among those facing significant work stress (Slopen et al., 2010).

- In Denmark, a study of 12,116 female nurses found that those reporting “much too high” work pressures had a 40 percent increased risk of heart disease (Allesøe et al., 2010).

- In the United States, a 10-year study of middle-aged workers found that involuntary job loss more than doubled their risk of a heart attack (Gallo et al., 2006). A 14-year study of 1059 women found that those with five or more trauma-related stress symptoms had three times the normal risk of heart disease (Kubzansky et al., 2009).

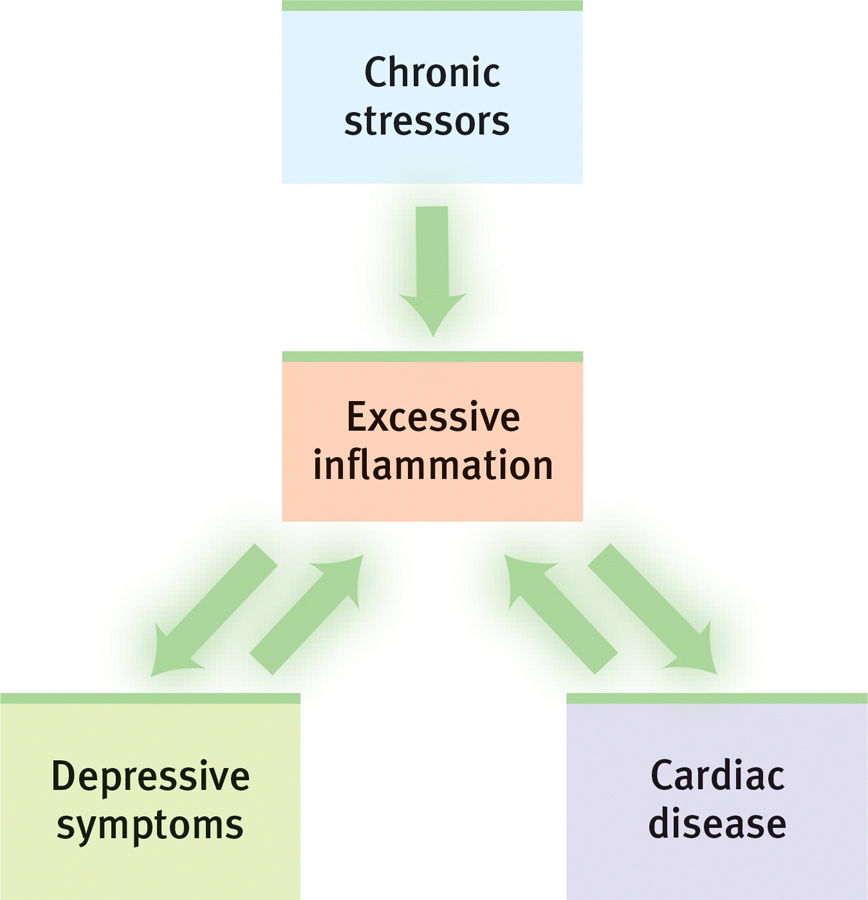

As FIGURE 40.7 illustrates, both heart disease and depression may result when chronic stress triggers persistent inflammation (Matthews, 2005; Miller & Blackwell, 2006). After a heart attack, stress and anxiety increase the risk of death or of another attack (Roest et al., 2010). As we have seen, stress disrupts the body’s disease-

Figure 40.7

Figure 40.7Stress→inflammation→heart disease and depression Gregory Miller and Ekin Blackwell (2006) report that chronic stress leads to persistent inflammation, which heightens the risk of both depression and clogged arteries.

499

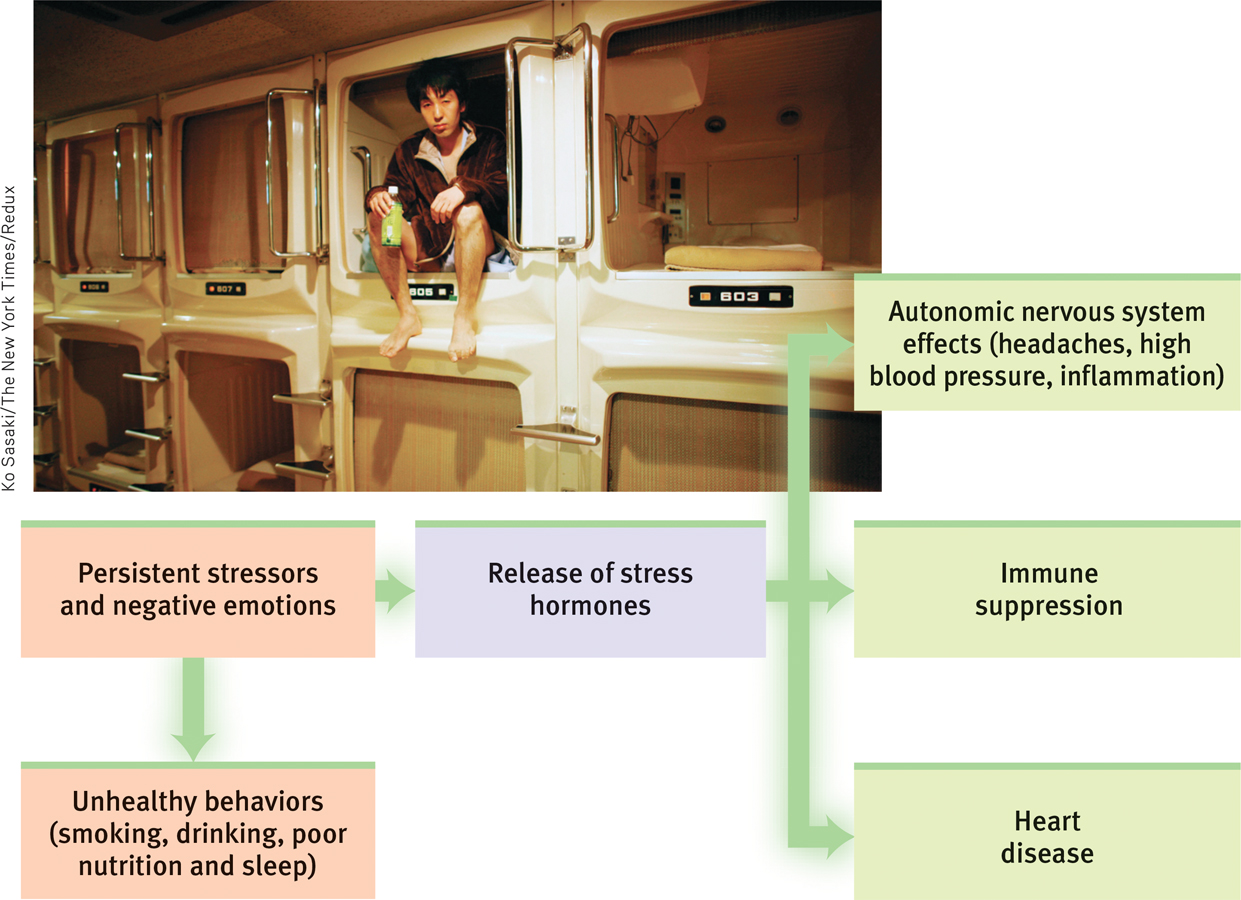

We can view the stress effect on our disease resistance as a price we pay for the benefits of stress (FIGURE 40.8). Stress invigorates our lives by arousing and motivating us. An unstressed life would hardly be challenging or productive.

Figure 40.8

Figure 40.8Stress can have a variety of health-

* * *

Psychological states are physiological events that influence other parts of our physiological system. Just pausing to think about biting into an orange section—

500

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- Which component of the Type A personality has been linked most closely to coronary heart disease?

Feeling angry and negative much of the time.

- How does Type D personality differ from Type A?

Type D individuals experience distress rather than anger, and they tend to suppress their negative emotions to avoid social disapproval.