42.1 The Fundamental Attribution Error

Our social behavior arises from our social cognition. Especially when the unexpected occurs, we want to understand and explain why people act as they do. After studying how people explain others’ behavior, Fritz Heider (1958) proposed an attribution theory: We can attribute the behavior to the person’s stable, enduring traits (a dispositional attribution), or we can attribute it to the situation (a situational attribution).

For example, in class, we notice that Juliette seldom talks. Over coffee, Jack talks nonstop. That must be the sort of people they are, we decide. Juliette must be shy and Jack outgoing. Such attributions—

David Napolitan and George Goethals (1979) demonstrated the fundamental attribution error in an experiment with Williams College students. They had students talk, one at a time, with a young woman who acted either cold and critical or warm and friendly. Before the conversations, the researchers told half the students that the woman’s behavior would be spontaneous. They told the other half the truth—

Did hearing the truth affect students’ impressions of the woman? Not at all! If the woman acted friendly, both groups decided she really was a warm person. If she acted unfriendly, both decided she really was a cold person. They attributed her behavior to her personal disposition even when told that her behavior was situational—that she was merely acting that way for the purposes of the experiment.

What Factors Affect Our Attributions?

The fundamental attribution error appears more often in some cultures than in others. Individualist Westerners more often attribute behavior to people’s personal traits. People in East Asian cultures are somewhat more sensitive to the power of the situation (Heine & Ruby, 2010; Kitayama et al., 2009). This difference has appeared in experiments that asked people to view scenes, such as a big fish swimming. Americans focused more on the individual fish, and Japanese people more on the whole scene (Chua et al., 2005; Nisbett, 2003).

We all commit the fundamental attribution error. Consider: Is your psychology instructor shy or outgoing?

If you answer “outgoing,” remember that you know your instructor from one situation—

519

When we explain our own behavior, we are sensitive to how behavior changes with the situation (Idson & Mischel, 2001). (An important exception: We more often attribute our intentional and admirable actions not to situations but to our own good reasons [Malle, 2006; Malle et al., 2007].) We also are sensitive to the power of the situation when we explain the behavior of people we know well and have seen in different contexts. We more often commit the fundamental attribution error when a stranger acts badly. Having only seen that red-

As we act, our eyes look outward; we see others’ faces, not our own. If we could take an observer’s point of view, would we become more aware of our own personal style? To test this idea, researchers have filmed two people interacting with a camera behind each person. Then they showed each person a replay of their interaction—

What Are the Consequences of Our Attributions?

Some 7 in 10 college women report having experienced a man misattributing her friendliness as a sexual come-on (Jacques-Tiura et al., 2007).

The way we explain others’ actions, attributing them to the person or the situation, can have important real-

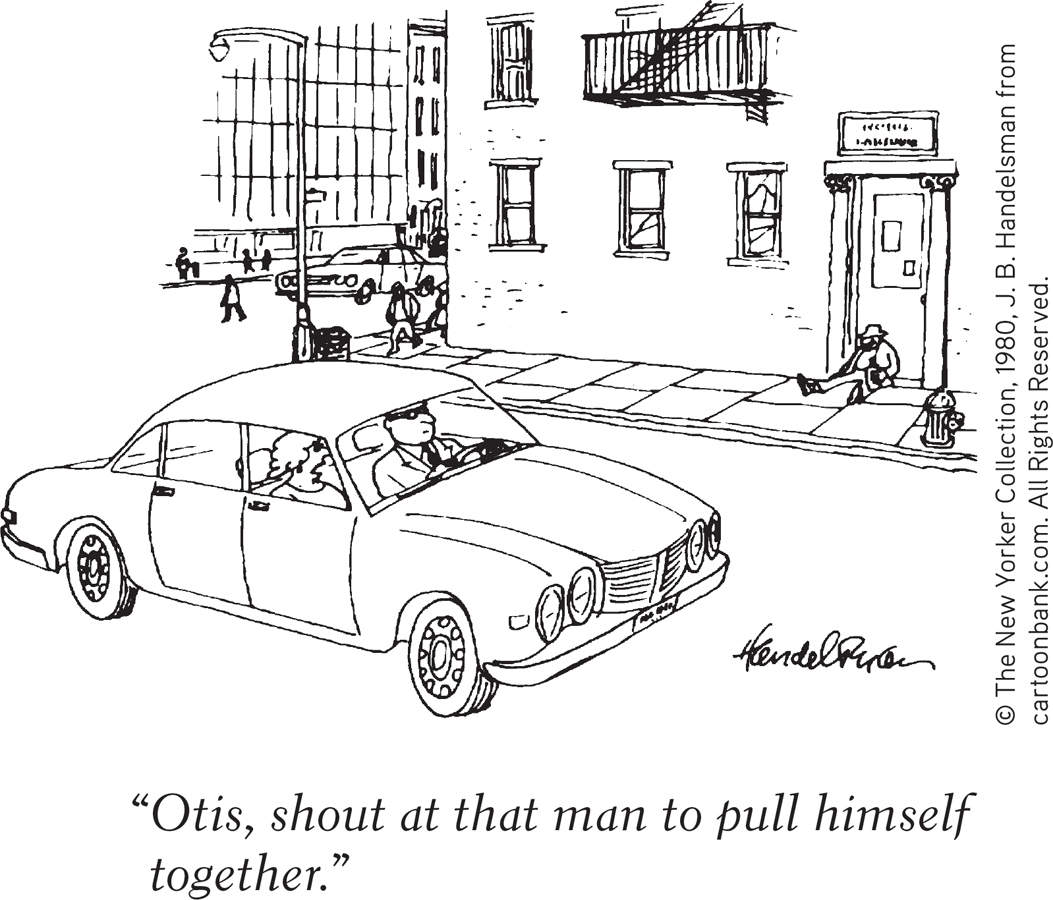

Finally, consider the social and economic effects of attribution. How do we explain poverty or unemployment? In Britain, India, Australia, and the United States (Furnham, 1982; Pandey et al., 1982; Wagstaff, 1982; Zucker & Weiner, 1993), political conservatives have tended to place the blame on the personal dispositions of the poor and unemployed: “People generally get what they deserve. Those who don’t work are freeloaders. Those who take initiative can still get ahead.” After inviting people to reflect on the power of choice—

The point to remember: Our attributions—

520

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.

For a quick interactive tutorial, visit LaunchPad’s Concept Practice: Making Attributions.