53.1 Dissociative Disorders

53-1 What are dissociative disorders, and why are they controversial?

Multiple personalities Chris Sizemore’s story, told in the book and movie, The Three Faces of Eve, gave early visibility to what is now called dissociative identity disorder.

Among the most bewildering disorders are the rare dissociative disorders, in which a person’s conscious awareness dissociates (separates) from painful memories, thoughts, and feelings. The result may be a fugue state, a sudden loss of memory or change in identity, often in response to an overwhelmingly stressful situation. Such was the case for one Vietnam veteran who was haunted by his comrades’ deaths, and who had left his World Trade Center office shortly before the 9/11 attack. Later, he disappeared on the way to work. Six months later, when he was discovered in a Chicago homeless shelter, he reported no memory of his identity or family (Stone, 2006).

Dissociation itself is not so rare. Any one of us may have a sense of being unreal, of being separated from our body, of watching ourselves as if in a movie. Sometimes we may say, “I was not myself at the time.” Perhaps you can recall getting up to go somewhere and ending up at some unintended location while your mind was preoccupied. Or perhaps you can play a well-practiced tune on a guitar or piano while talking to someone. When we face trauma, dissociative detachment may protect us from being overwhelmed by emotion.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

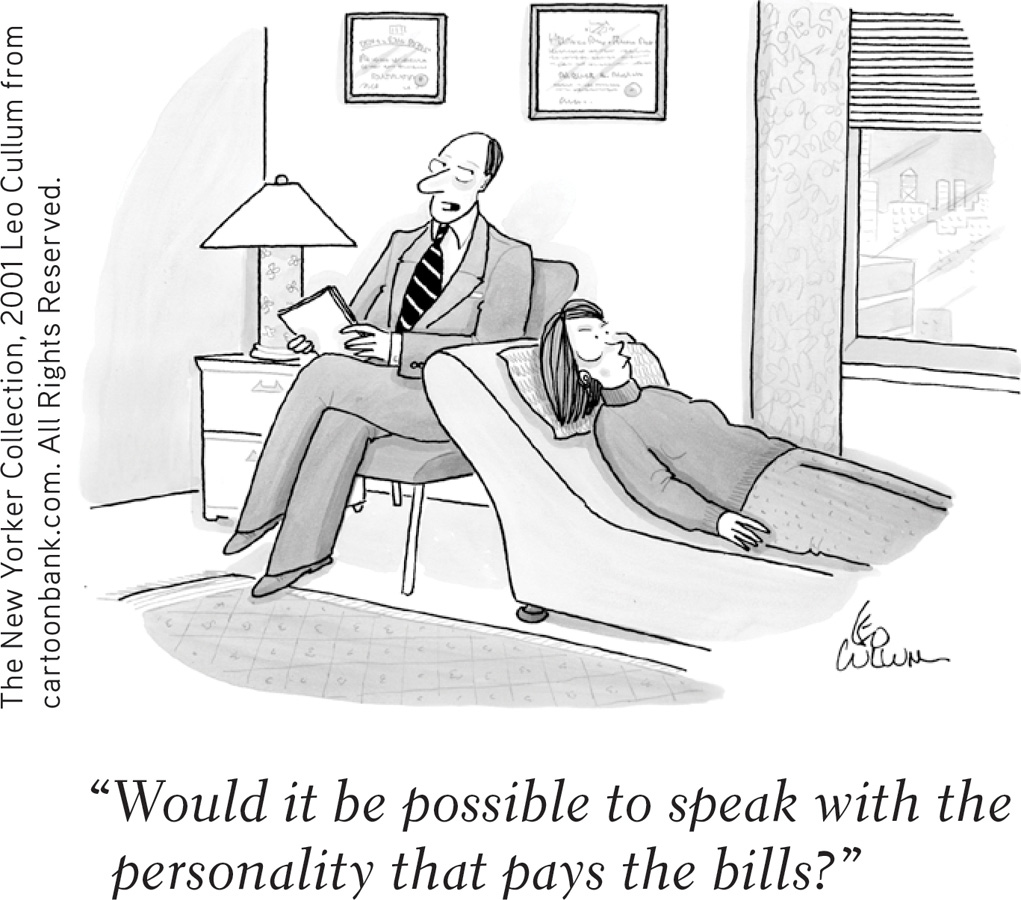

The “Hillside Strangler” Kenneth Bianchi is shown here at his trial.

A massive dissociation of self from ordinary consciousness occurs in dissociative identity disorder (DID), in which two or more distinct identities—each with its own voice and mannerisms—seem to control a person’s behavior at different times. Thus, the person may be prim and proper one moment, loud and flirtatious the next. Typically, the original personality denies any awareness of the other(s).

People diagnosed with DID (formerly called multiple personality disorder) are rarely violent. But cases have been reported of dissociations into a “good” and a “bad” (or aggressive) personality—a modest version of the Dr. Jekyll–Mr. Hyde split immortalized in Robert Louis Stevenson’s story. One unusual case involved Kenneth Bianchi, accused in the “Hillside Strangler” rapes and murders of 10 California women. During a hypnosis session, Bianchi’s psychologist “called forth” a hidden personality: “I’ve talked a bit to Ken, but I think that perhaps there might be another part of Ken that … maybe feels somewhat differently from the part that I’ve talked to…. Would you talk with me, Part, by saying, ‘I’m here’?” Bianchi answered “Yes” and then claimed to be “Steve” (Watkins, 1984).

Speaking as Steve, Bianchi stated that he hated Ken because Ken was nice and that he (Steve), aided by a cousin, had murdered women. He also claimed Ken knew nothing about Steve’s existence and was innocent of the murders. Was Bianchi’s second personality a trick, simply a way of disavowing responsibility for his actions? Indeed, Bianchi—a practiced liar who had read about multiple personality in psychology books—was later convicted.

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Skeptics have raised serious concerns about DID. First, instead of being a true disorder, could DID be an extension of our normal capacity for personality shifts? Nicholas Spanos (1986, 1994, 1996) asked college students to pretend they were accused murderers being examined by a psychiatrist. Given the same hypnotic treatment Bianchi received, most spontaneously expressed a second personality. This discovery made Spanos wonder: Are dissociative identities simply a more extreme version of our capacity to vary the “selves” we present—as when we display a goofy, loud self while hanging out with friends, and a subdued, respectful self around grandparents? Are clinicians who discover multiple personalities merely triggering role playing by fantasy-prone people? Do these patients, like actors who commonly report “losing themselves” in their roles, then convince themselves of the authenticity of their own role enactments? Spanos was no stranger to this line of thinking. In a related research area, he had also raised these questions about the hypnotic state. Because most DID patients are highly hypnotizable, whatever explains one condition—dissociation or role playing—may help explain the other.

“Pretense may become reality.”

Skeptics also find it suspicious that the disorder has such a short and localized history. Between 1930 and 1960, the number of North American DID diagnoses averaged 2 per decade. By the 1980s, when the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) contained the first formal code for this disorder, the number exploded to more than 20,000 (McHugh, 1995a). The average number of displayed personalities also mushroomed—from 3 to 12 per patient (Goff & Simms, 1993). This disorder is much less prevalent outside North America, although in other cultures people may be said to be “possessed” by an alien spirit (Aldridge-Morris, 1989; Kluft, 1991). In Britain, DID—which some have considered “a wacky American fad” (Cohen, 1995)—is rare. In India and Japan, it is essentially nonexistent (or at least unreported).

Widespread dissociation Shirley Mason was a psychiatric patient diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder. Her life formed the basis of the bestselling book, Sybil (Schreiber, 1973), and of two movies. Some argue that the book and movies’ popularity fueled the dramatic rise in diagnoses of dissociative identity disorder. Skeptics wonder whether she actually had dissociative identity disorder (Nathan, 2011).

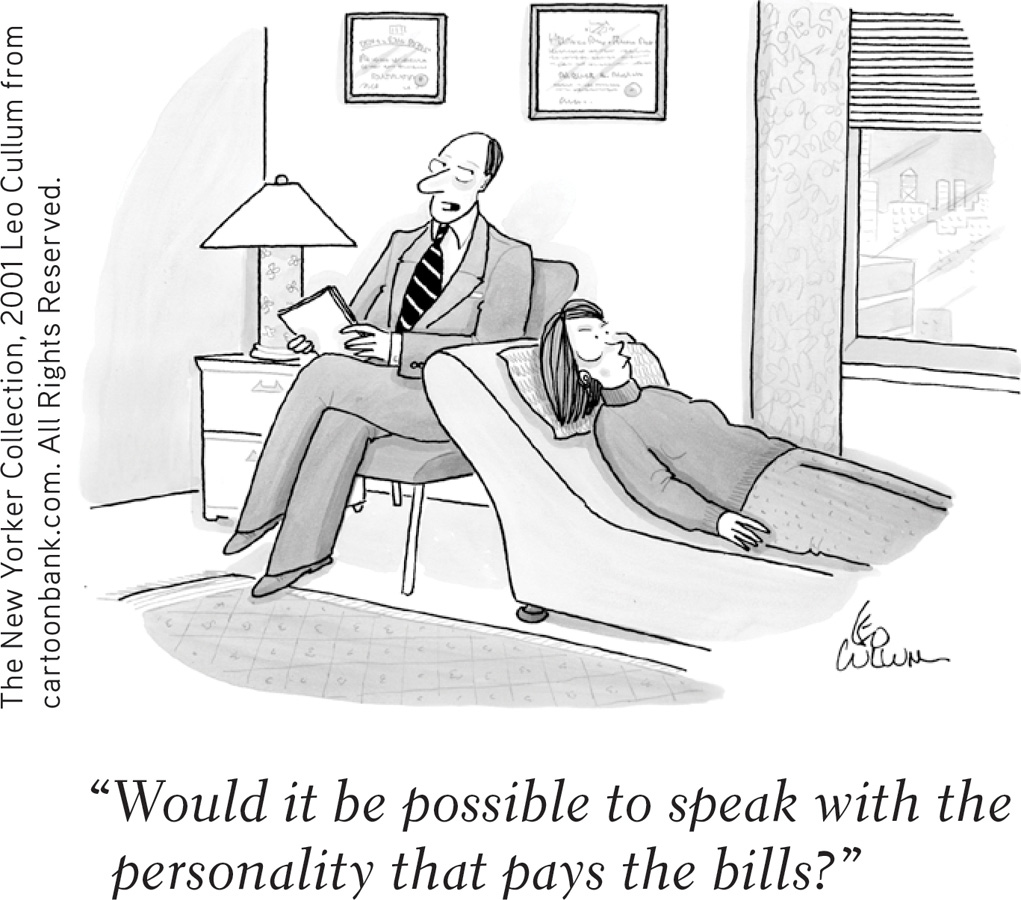

Such findings, skeptics note, point to a cultural phenomenon—a disorder created by therapists in a particular social context (Merskey, 1992). Rather than being provoked by trauma, dissociative symptoms tend to be exhibited by suggestible, fantasy-prone people (Giesbrecht et al., 2008, 2010). Patients do not enter therapy saying “Allow me to introduce myselves.” Instead, charge the critics, some therapists go fishing for multiple personalities: “Have you ever felt like another part of you does things you can’t control? Does this part of you have a name? Can I talk to the angry part of you?” Once patients permit a therapist to talk, by name, “to the part of you that says those angry things,” they begin acting out the fantasy. The result may be the experience of another self.

Other researchers and clinicians believe DID is a real disorder. They find support for this view in the distinct body and brain states associated with differing personalities (Putnam, 1991). Handedness sometimes switches with personality (Henninger, 1992). Shifts in visual acuity and eye-muscle balance have been recorded as patients switched personalities, but not as control group members tried to simulate DID behavior (Miller et al., 1991). Abnormal brain anatomy and activity can also accompany DID. Brain scans show shrinkage in areas that aid memory and detection of threat (Vermetten et al., 2006). Heightened activity appears in brain areas associated with the control and inhibition of traumatic memories (Elzinga et al., 2007).

“Though this be madness, yet there is method in ‘t.”

William Shakespeare, Hamlet, 1600

Both the psychodynamic and learning perspectives have interpreted DID symptoms as ways of coping with anxiety. Some psychodynamic theorists see them as defenses against the anxiety caused by the eruption of unacceptable impulses. In this view, a second personality enables the discharge of forbidden impulses. Learning theorists see dissociative disorders as behaviors reinforced by anxiety reduction.

Some clinicians include dissociative disorders under the umbrella of posttraumatic stress disorder—a natural, protective response to traumatic experiences during childhood (Putnam, 1995; Spiegel, 2008). Many DID patients recall being physically, sexually, or emotionally abused as children (Gleaves, 1996; Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In one study of 12 murderers diagnosed with DID, 11 had suffered severe, torturous child abuse (Lewis et al., 1997). One had been set afire by his parents. Another had been used in child pornography and was scarred from being made to sit on a stove burner. Some critics wonder, however, whether vivid imagination or therapist suggestion contributed to such recollections (Kihlstrom, 2005).

So the debate continues. On one side are those who believe multiple personalities are the desperate efforts of people trying to detach from a horrific existence. On the other are the skeptics who think DID is a condition constructed out of the therapist-patient interaction and acted out by fantasy-prone, emotionally vulnerable people. If the skeptics’ view wins, predicted psychiatrist Paul McHugh (1995b), “this epidemic will end in the way that the witch craze ended in Salem. The [multiple personality phenomenon] will be seen as manufactured.”

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- The psychodynamic and learning perspectives agree that dissociative identity disorder symptoms are ways of dealing with anxiety. How do their explanations differ?

The psychodynamic explanation of DID symptoms is that they are defenses against anxiety generated by unacceptable urges. The learning perspective attempts to explain these symptoms as behaviors that have been reinforced by relieving anxiety in the past.