53.3 Eating Disorders

53-

Our bodies are naturally disposed to maintain a steady weight, including stored energy reserves for times when food becomes unavailable. But sometimes psychological influences overwhelm biological wisdom. This becomes painfully clear in three eating disorders.

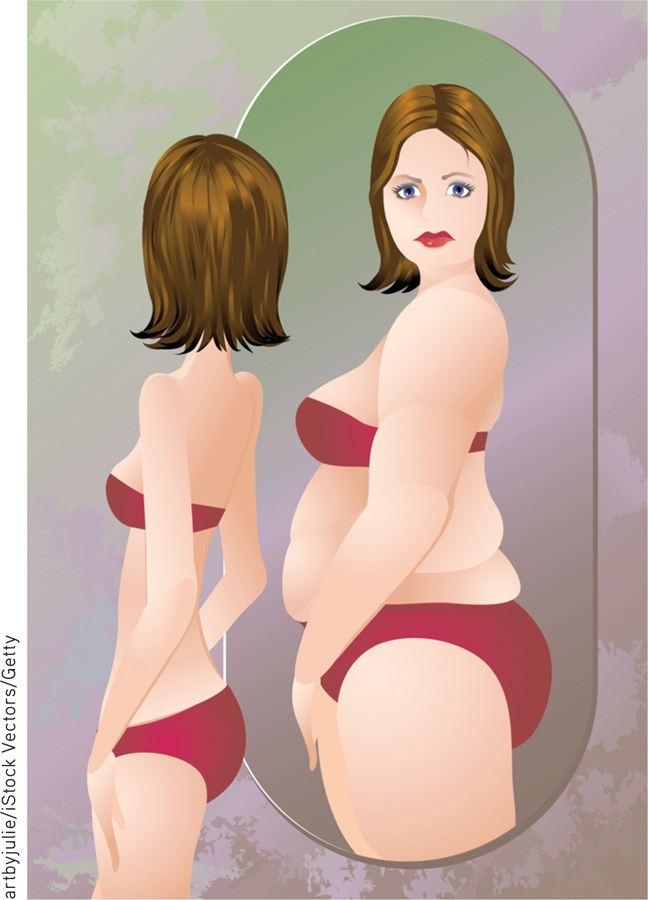

- Anorexia nervosa typically begins as a weight-

loss diet. People with anorexia— usually adolescents and 9 out of 10 times females— drop significantly below normal weight. Yet they feel fat, fear being fat, remain obsessed with losing weight, and sometimes exercise excessively. About half of those with anorexia display a binge- purge- depression cycle. - Bulimia nervosa may also be triggered by a weight-

loss diet, broken by gorging on forbidden foods. Binge- purge eaters— mostly women in their late teens or early twenties— eat in spurts, sometimes influenced by negative emotion or by friends who are bingeing (Crandall, 1988; Haedt- Matt & Keel, 2011). In a cycle of repeating episodes, overeating is followed by compensatory purging (through vomiting or laxative use), fasting, or excessive exercise (Wonderlich et al., 2007). Preoccupied with food (craving sweet and high- fat foods), and fearful of becoming overweight, binge- purge eaters experience bouts of depression, guilt, and anxiety during and following binges (Hinz & Williamson, 1987; Johnson et al., 2002). Unlike anorexia, bulimia is marked by weight fluctuations within or above normal ranges, making the condition easy to hide. - Those with binge-eating disorder engage in significant bouts of overeating, followed by remorse. But they do not purge, fast, or exercise excessively and thus may be overweight.

652

A U.S. National Institute of Mental Health-

Understanding Eating Disorders

Eating disorders do not provide (as some have speculated) a telltale sign of childhood sexual abuse (Smolak & Murnen, 2002; Stice, 2002). The family environment may provide a fertile ground for the growth of eating disorders in other ways, however.

- Mothers of girls with eating disorders tend to focus on their own weight and on their daughters’ weight and appearance (Pike & Rodin, 1991).

- Families of those with bulimia tend to have a higher-than-usual incidence of childhood obesity and negative self-evaluation (Jacobi et al., 2004).

- Families of those with anorexia tend to be competitive, high-achieving, and protective (Berg et al., 2014; Pate et al., 1992; Yates, 1989, 1990).

Those with eating disorders often have low self-

Heredity also matters. Identical twins share these disorders more often than fraternal twins do (Culbert et al., 2009; Klump et al., 2009; Root et al., 2010). Scientists are now searching for culprit genes, which may influence the body’s available serotonin and estrogen (Klump & Culbert, 2007). In one analysis of 15 studies, having a gene that reduced available serotonin added 30 percent to a person’s risk of anorexia or bulimia (Calati et al., 2011).

But these disorders also have cultural and gender components. Ideal shapes vary across culture and time. In impoverished areas of the world, including much of Africa—

“Why do women have such low self-esteem? There are many complex psychological and societal reasons, by which I mean Barbie.”

Dave Barry, 1999

Those most vulnerable to eating disorders are also those (usually women or gay men) who most idealize thinness and have the greatest body dissatisfaction (Feldman & Meyer, 2010; Kane, 2010; Stice et al., 2010). Should it surprise us, then, that when women view real and doctored images of unnaturally thin models and celebrities, they often feel ashamed, depressed, and dissatisfied with their own bodies—

653

There is, however, more to body dissatisfaction and anorexia than media effects (Ferguson et al., 2011). Peer influences, such as teasing, also matter. So does affluence, increased marriage age, and especially, competition for available mates.

Nevertheless, the sickness of today’s eating disorders stems in part from today’s weight-

If cultural learning contributes to eating behavior, then might prevention programs increase acceptance of one’s body? Reviews of prevention studies answer Yes. They seem especially effective if the programs are interactive and focused on girls over age 15 (Beintner et al., 2012; Stice et al., 2007; Vocks et al., 2010).

***

A growing number of people, especially teenagers and young adults are being diagnosed with psychological disorders. Although mindful of their pain, we can also be encouraged by their successes. Many live satisfying lives. Some pursue brilliant careers, as did 18 U.S. presidents, including the periodically depressed Abraham Lincoln, according to one psychiatric analysis of their biographies (Davidson et al., 2006). The bewilderment, fear, and sorrow caused by psychological disorders are real. But, as this text’s discussion of therapy shows, hope, too, is real.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- People with ___________ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) continue to want to lose weight even when they are underweight. Those with ____________ (anorexia nervosa/bulimia nervosa) tend to have weight that fluctuates within or above normal ranges.

anorexia nervosa; bulimia nervosa

654