54.3 Humanistic Therapies

54-

The humanistic perspective emphasizes people’s inherent potential for self-

- Humanistic therapists aim to boost people’s self-fulfillment by helping them grow in self-awareness and self acceptance.

- Promoting this growth, not curing illness, is the therapy focus. Thus, those in therapy became “clients” or just “persons” rather than “patients” (a change many other therapists have adopted).

- The path to growth is taking immediate responsibility for one’s feelings and actions, rather than uncovering hidden determinants.

- Conscious thoughts are more important than the unconscious.

- The present and future are more important than the past. The goal is to explore feelings as they occur, rather than achieve insights into the childhood origins of the feelings.

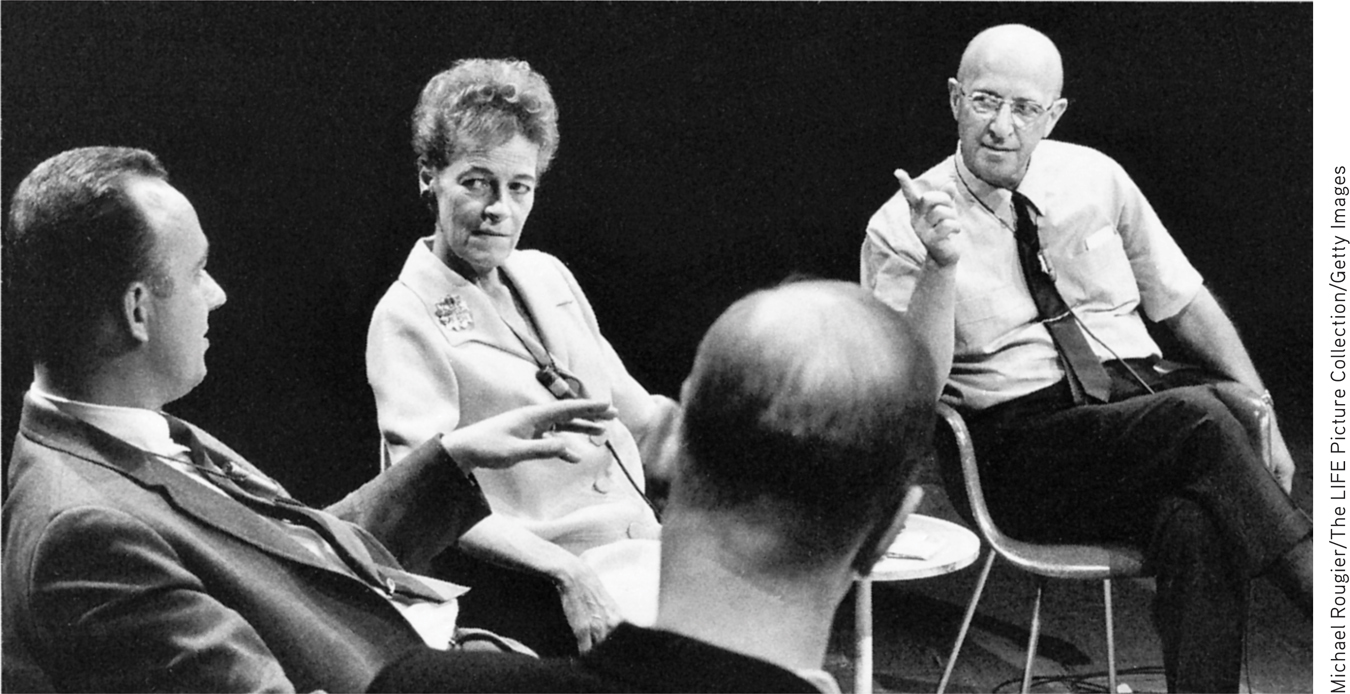

Carl Rogers (1902–

Believing that most people possess the resources for growth, Rogers (1961, 1980) encouraged therapists to exhibit genuineness, acceptance, and empathy. When therapists drop their facades and genuinely express their true feelings, when they enable their clients to feel unconditionally accepted, and when they empathically sense and reflect their clients’ feelings, the clients may deepen their self-

Hearing has consequences. When I truly hear a person and the meanings that are important to him at that moment, hearing not simply his words, but him, and when I let him know that I have heard his own private personal meanings, many things happen. There is first of all a grateful look. He feels released. He wants to tell me more about his world. He surges forth in a new sense of freedom. He becomes more open to the process of change.

I have often noticed that the more deeply I hear the meanings of the person, the more there is that happens. Almost always, when a person realizes he has been deeply heard, his eyes moisten. I think in some real sense he is weeping for joy. It is as though he were saying, “Thank God, somebody heard me. Someone knows what it’s like to be me.”

“We have two ears and one mouth that we may listen the more and talk the less.”

Zeno, 335–263 B.C.E., Diogenes Laertius

“Hearing” refers to Rogers’ technique of active listening—echoing, restating, and seeking clarification of what the person expresses (verbally or nonverbally) and acknowledging the expressed feelings. Active listening is now an accepted part of therapeutic counseling practices in many schools, colleges, and clinics. The counselor listens attentively and interrupts only to restate and confirm feelings, to accept what is being expressed, or to seek clarification. The following brief excerpt between Rogers and a male client illustrates how he sought to provide a psychological mirror that would help clients see themselves more clearly.

Rogers: Feeling that now, hm? That you’re just no good to yourself, no good to anybody. Never will be any good to anybody. Just that you’re completely worthless, huh?—Those really are lousy feelings. Just feel that you’re no good at all, hm?

662

Client: Yeah. (Muttering in low, discouraged voice) That’s what this guy I went to town with just the other day told me.

Rogers: This guy that you went to town with really told you that you were no good? Is that what you’re saying? Did I get that right?

Client: M-

Rogers: I guess the meaning of that if I get it right is that here’s somebody that—

Client: (Rather defiantly) I don’t care though.

Rogers: You tell yourself you don’t care at all, but somehow I guess some part of you cares because some part of you weeps over it.

(Meador & Rogers, 1984, p. 167)

Can a therapist be a perfect mirror, without selecting and interpreting what is reflected? Rogers conceded that one cannot be totally nondirective. Nevertheless, he believed that the therapist’s most important contribution is to accept and understand the client. Given a nonjudgmental, grace-

If you want to listen more actively in your own relationships, three Rogers-

- Paraphrase. Rather than saying “I know how you feel,” check your understandings by summarizing the person’s words in your own words.

- Invite clarification. “What might be an example of that?” may encourage the person to say more.

- Reflect feelings. “It sounds frustrating” might mirror what you’re sensing from the person’s body language and intensity.