56.4 Therapeutic Lifestyle Change

56-

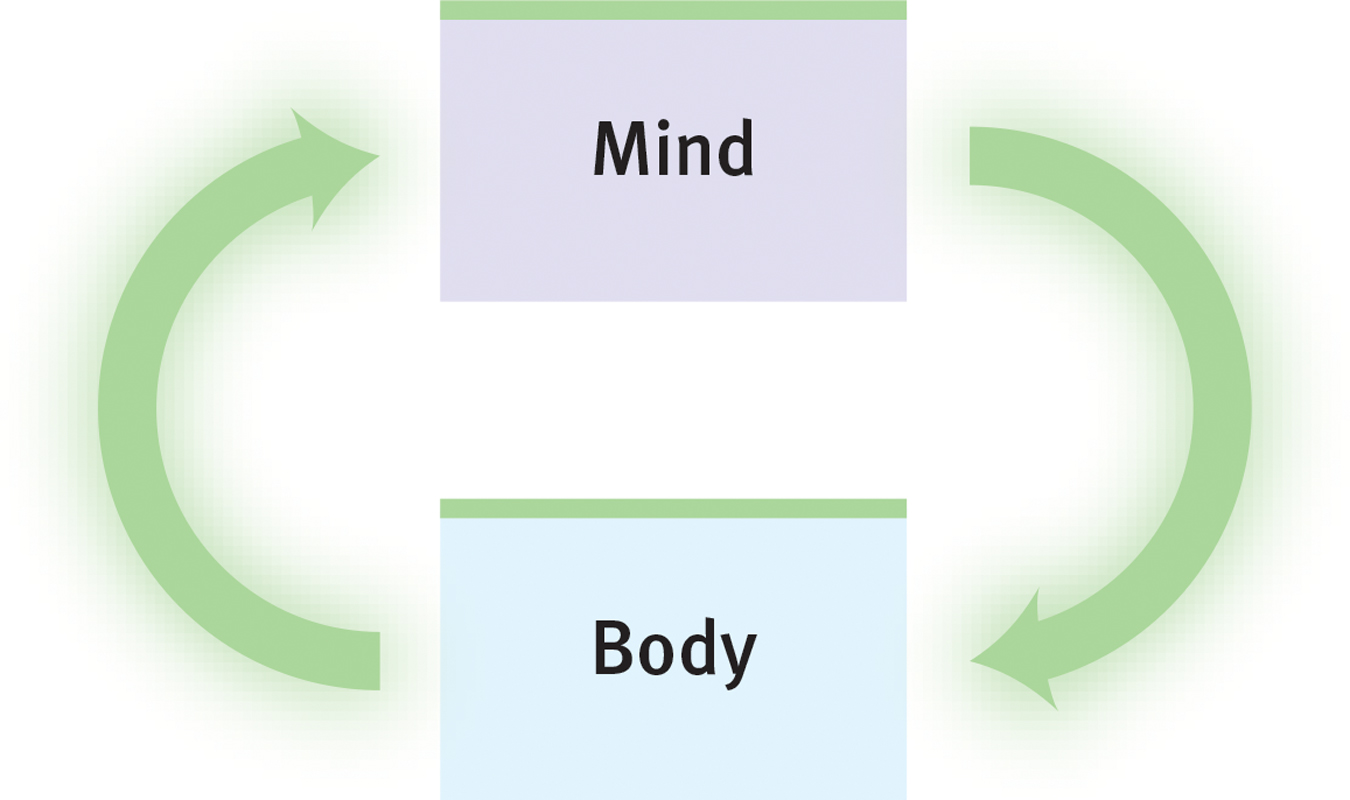

The effectiveness of the biomedical therapies reminds us of a fundamental lesson: We find it convenient to talk of separate psychological and biological influences, but everything psychological is also biological (FIGURE 56.4). Every thought and feeling depends on the functioning brain. Every creative idea, every moment of joy or anger, every period of depression emerges from the electrochemical activity of the living brain. The influence is two-

Figure 56.4

Figure 56.4Mind-

Anxiety disorders, obsessive-

That lesson is being applied by Stephen Ilardi (2009) in training seminars promoting therapeutic lifestyle change. Human brains and bodies were designed for physical activity and social engagement, he notes. Our ancestors hunted, gathered, and built in groups. Indeed, those whose way of life entails strenuous physical activity, strong community ties, sunlight exposure, and plenty of sleep (think of foraging bands in Papua New Guinea, or Amish farming communities in North America) rarely experience depression. For both children and adults, outdoor activity in natural environments—

The Ilardi team was also impressed by research showing that regular aerobic exercise rivals the healing power of antidepressant drugs, and that a complete night’s sleep boosts mood and energy. So they invited small groups of people with depression to undergo a 12-

689

- Aerobic exercise, 30 minutes a day, at least 3 times weekly (increasing fitness and vitality, stimulating endorphins)

- Adequate sleep, with a goal of 7 to 8 hours a night (increasing energy and alertness, boosting immunity)

- Light exposure, at least 30 minutes each morning with a light box (amplifying arousal, influencing hormones)

- Social connection, with less alone time and at least two meaningful social engagements weekly (satisfying the human need to belong)

- Anti-rumination, by identifying and redirecting negative thoughts (enhancing positive thinking)

- Nutritional supplements, including a daily fish oil supplement with omega-3 fatty acids (supporting healthy brain functioning)

In one study of 74 people, 77 percent of those who completed the program experienced relief from depressive symptoms, compared with 19 percent in those assigned to a treatment-

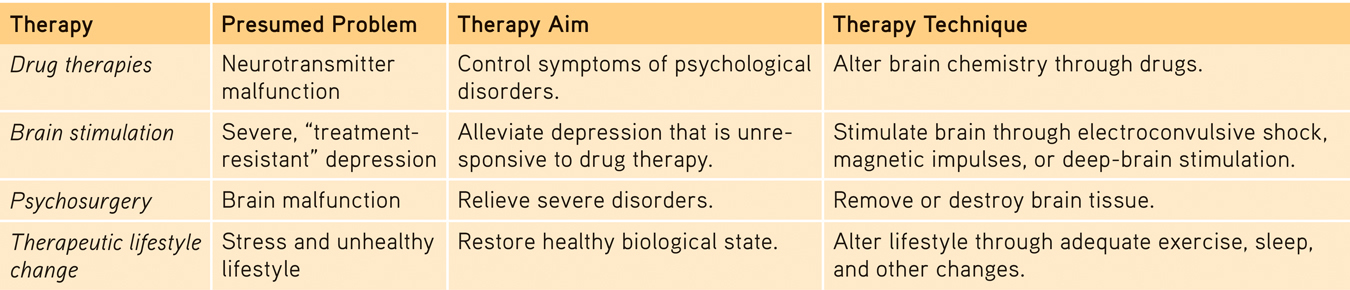

TABLE 56.1 summarizes some aspects of the biomedical therapies we’ve discussed.

Table 56.1

Table 56.1Comparing Biomedical Therapies

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE

- What are some examples of lifestyle changes we can make to enhance our mental health?

Exercise regularly, get enough sleep, get more exposure to light (get outside and/or use a light box), nurture important relationships, redirect negative thinking, and eat a diet rich in omega-