Module 6 Introduction

Tools of Discovery and Older Brain Structures

Tools of Discovery and Older Brain Structures

In a jar on a display shelf in Cornell University’s psychology department resides the well-preserved brain of Edward Bradford Titchener, a late-nineteenth-century experimental psychologist and proponent of the study of consciousness. Imagine yourself gazing at that wrinkled mass of grayish tissue, wondering if in any sense Titchener is still in there.1

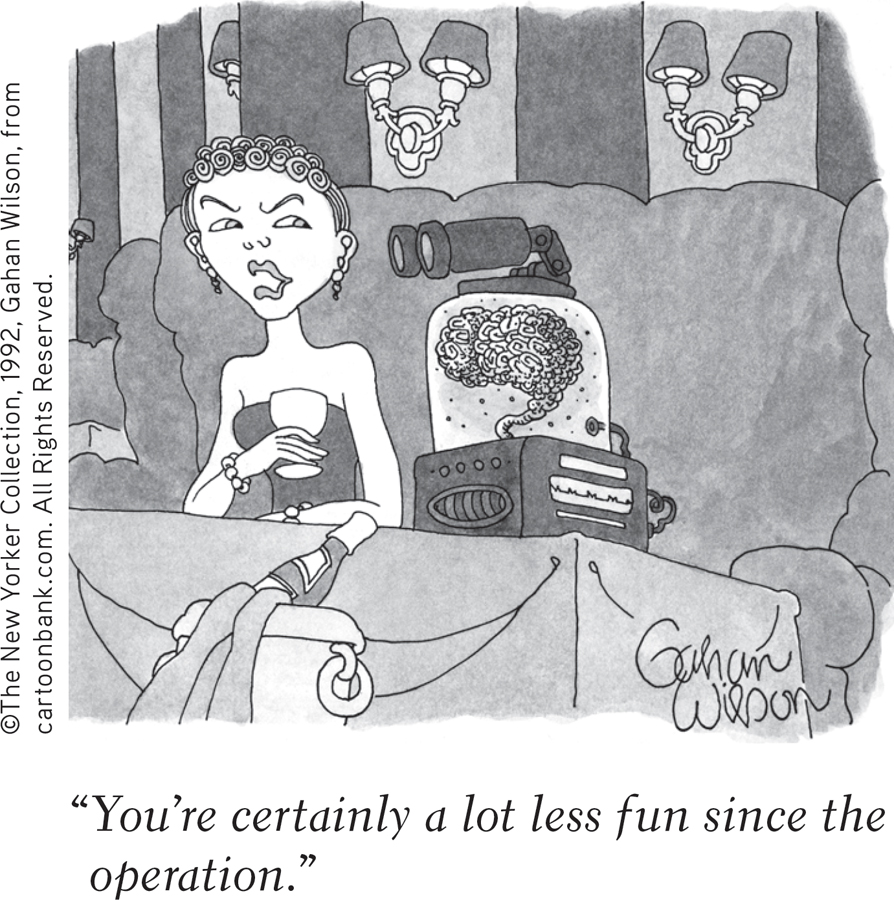

You might answer that, without the living whir of electrochemical activity, there could be nothing of Titchener in his preserved brain. Consider, then, an experiment about which the inquisitive Titchener himself might have daydreamed. Imagine that just moments before his death, someone had removed Titchener’s brain and kept it alive by feeding it enriched blood. Would Titchener still be in there? Further imagine that someone then transplanted the still-living brain into the body of a person whose own brain had been severely damaged. To whose home should the recovered patient return?

“I am a brain, Watson. The rest of me is a mere appendix.”

Sherlock Holmes, in Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone”

That we can imagine such questions illustrates how convinced we are that we live “somewhere north of the neck” (Fodor, 1999). And for good reason: The brain enables the mind—seeing, hearing, smelling, feeling, remembering, thinking, speaking, dreaming. Moreover, it is the brain that self-reflectively analyzes the brain. When we’re thinking about our brain, we’re thinking with our brain—by firing across millions of synapses and releasing billions of neurotransmitter molecules. The effect of hormones on experiences such as love reminds us that we would not be of the same mind if we were a bodiless brain. Brain + body = mind. Nevertheless, say neuroscientists, the mind is what the brain does. Brain, behavior, and cognition are an integrated whole. But precisely where and how are the mind’s functions tied to the brain? Let’s first see how scientists explore such questions.

Tools of Discovery and Older Brain Structures

Tools of Discovery and Older Brain Structures