16.1 Social Thinking

OUR SOCIAL BEHAVIOR arises from our social cognition. Especially when the unexpected occurs, we analyze why people act as they do. Does her warmth reflect romantic interest, or is that how she relates to everyone? Does his absenteeism signify illness? Laziness? A stressful work atmosphere? Was the horror of 9/11 the work of crazed people, or of ordinary people corrupted by life events?

16.1.1 Attributing Behavior to Persons or to Situations

1: How do we tend to explain others’ behavior and our own?

After studying how people explain others’ behavior, Fritz Heider (1958) proposed an attribution theory. Heider noted that people usually attribute others’ behavior either to their internal dispositions or to their external situations. A teacher, for example, may wonder whether a child’s hostility reflects an aggressive personality (a dispositional attribution) or a reaction to stress or abuse (a situational attribution).

In class, we notice that Juliette seldom talks; over coffee, Jack talks nonstop. Attributing their behaviors to their personal dispositions, we decide Juliette is shy and Jack is outgoing. Because people do have enduring personality traits, such attributions are sometimes valid. However, we often fall prey to the fundamental attribution error, by overestimating the influence of personality and underestimating the influence of situations. In class, Jack may be as quiet as Juliette. Catch Juliette at a party and you may hardly recognize your quiet classmate.

An experiment by David Napolitan and George Goethals (1979) illustrated the phenomenon. They had Williams College students talk, one at a time, with a young woman who acted either aloof and critical or warm and friendly. Beforehand, they told half the students that the woman’s behavior would be spontaneous. They told the other half the truth—that she had been instructed to act friendly (or unfriendly). What do you suppose was the effect of being told the truth?

There was no effect. The students disregarded the information. If the woman acted friendly, they inferred she really was a warm person. If she acted unfriendly, they inferred she really was a cold person. In other words, they attributed her behavior to her personal disposition even when told that her behavior was situational—that she was merely acting that way for the purposes of the experiment. Although the fundamental attribution error occurs in all cultures studied, this tendency to attribute behavior to people’s dispositions runs especially strong in individualistic Western countries. In East Asian cultures, for example, people are more sensitive to the power of the situation (Masuda & Kitayama, 2004).

Question 16.1

Write a question that focuses on a key concept in the section you just read, then compose an answer to this question.

+LS3gOJVJp29YZDDrcjjQlH9+Pd6Tv57OzTh89AMk0w7tryEoAfmWi0zaI9xdTPz +JOm5G4OK5HlV1pyreTv1G2GVHHJFZzHko20iZzNoqdRNKI4aiuCkA71TBEyXd41zeEarWv0MsY4QKZAxYUDVQ==16.1.2 The Fundamental Attribution Error

You have surely committed the fundamental attribution error. In judging whether your psychology instructor is shy or outgoing, you have perhaps by now inferred that he or she has an outgoing personality. But you know your instructor only from the classroom, a situation that demands outgoing behavior. Catch the instructor in a different situation and you might be surprised. Outside their assigned roles, professors seem less professorial, presidents less presidential, servants less servile.

The instructor, on the other hand, observes his or her own behavior in many different situations—in the classroom, in meetings, at home—and so might say, “Me, outgoing? It all depends on the situation. In class or with good friends, yes, I’m outgoing. But at conventions I’m really rather shy.” When explaining our own behavior, or the behavior of those we know well and see in varied situations, we are sensitive to how behavior changes with the situation (Idson & Mischel, 2001). (An important exception is our own intentional and admirable actions, which we more often attribute to our own good reasons than to situational causes [Malle, 2006; Malle et al., 2007]).

When explaining others’ behavior, particularly the behavior of strangers we have observed in only one type of situation, we often commit the fundamental attribution error: We disregard the situation and leap to unwarranted conclusions about their personality traits. Many people initially assumed the 9/11 terrorists were obviously crazy, when actually they went unnoticed in their neighborhoods, health clubs, and favorite restaurants.

Researchers who have reversed the perspectives of actor and observer—by having each view a replay of the situation filmed from the other’s perspective—have also reversed the attributions (Lassiter & Irvine, 1986; Storms, 1973). Seeing the world from the actor’s perspective, the observers better appreciate the situation. (As you act, your eyes look outward; you see others’ faces, not your own.) Taking the observer’s point of view, the actors better appreciate their own personal style. Reflecting on our past selves of 5 or 10 years ago also switches our perspective. We now adopt an observer’s perspective and attribute our behavior mostly to our traits (Pronin & Ross, 2006). Likewise, in another 5 or 10 years, our today’s self may seem like another person.

16.1.3 The Effects of Attribution

• Some 7 in 10 college women report having experienced a man misattributing her friendliness as a sexual come-on (Jacques-Tiura et al., 2007). •

In everyday life we often struggle to explain others’ actions. A jury must decide whether a shooting was malicious or in self-defense. An interviewer must judge whether the applicant’s geniality is genuine. A person must decide whether to attribute another’s friendliness to sexual interest. When we make such judgments, our attributions—either to the person or to the situation—have important consequences (Fincham & Bradbury, 1993; Fletcher et al., 1990). Happily married couples attribute a spouse’s tart-tongued remark to a temporary situation (“She must have had a bad day at work”). Unhappily married couples attribute the same remark to a mean disposition (“Why did I marry such a hostile person?”).

Or consider the political effects of attribution. How do you explain poverty or unemployment? Researchers in Britain, India, Australia, and the United States (Furnham, 1982; Pandey et al., 1982; Wagstaff, 1982; Zucker & Weiner, 1993) report that political conservatives tend to attribute such social problems to the personal dispositions of the poor and unemployed themselves: “People generally get what they deserve. Those who don’t work are often freeloaders. Anybody who takes the initiative can still get ahead.” “Society is not to blame for crime, criminals are,” said one conservative U.S. presidential candidate (Dole, 1996). Political liberals (and social scientists) are more likely to blame past and present situations: “If you or I had to live with the same poor education, lack of opportunity, and discrimination, would we be any better off?” To understand and prevent terrorism, they say, consider the situations that breed terrorists. Better to drain the swamps than swat the mosquitoes.

Managers’ attributions also have effects. In evaluating employees, they are likely to attribute poor performance to personal factors, such as low ability or lack of motivation. But remember the actor’s viewpoint: Workers doing poorly on a job recognize situational influences, such as inadequate supplies, poor working conditions, difficult co-workers, or impossible demands (Rice, 1985).

The point to remember: Our attributions—to individuals’ dispositions or to their situations—should be made carefully. They have real consequences.

16.1.4 Attitudes and Actions

2: Does what we think affect what we do, or does what we do affect what we think?

Attitudes are feelings, often influenced by our beliefs, that predispose our reactions to objects, people, and events. If we believe someone is mean, we may feel dislike for the person and act unfriendly.

16.1.5 Attitudes Affect Actions

Our attitudes often predict our behavior. Al Gore’s movie An Inconvenient Truth and the Alliance for Climate Protection it has spawned have a simple premise: Public opinion about the reality and dangers of global climate change can change, with effects on both personal behaviors and public policies. Indeed, by the end of 2007, an analysis of international opinion surveys by WorldPublicOpinion.org showed “widespread and growing concern about climate change. Large majorities believe that human activity causes climate change and favor policies designed to reduce emissions.” Thanks to the mass persuasion campaign, many corporations, as well as campuses, are now “going green.”

This tidal wave of change has occurred as people have engaged scientific evidence and arguments and responded with favorable thoughts. Such central route persuasion occurs mostly when people are naturally analytical or involved in the issue. When issues don’t engage systematic thinking, persuasion may occur through a faster peripheral route, as people respond to incidental cues, such as endorsements by respected people, and make snap judgments. Because central route persuasion is more thoughtful and less superficial, it is more durable and more likely to influence behavior.

Other factors, including the external situation, also influence behavior. Strong social pressures can weaken the attitude-behavior connection (Wallace et al., 2005). For example, the American public’s overwhelming support for President George W. Bush’s preparation to attack Iraq motivated Democratic leaders to vote to support Bush’s war plan, despite their private reservations (Nagourney, 2002). Nevertheless, attitudes do affect behavior when external influences are minimal, especially when the attitude is stable, specific to the behavior, and easily recalled (Glasman & Albarracín, 2006). One experiment used vivid, easily recalled information to persuade people that sustained tanning put them at risk for future skin cancer. One month later, 72 percent of the participants, and only 16 percent of those in a waitlist control group, had lighter skin (McClendon & Prentice-Dunn, 2001).

16.1.6 Actions Affect Attitudes

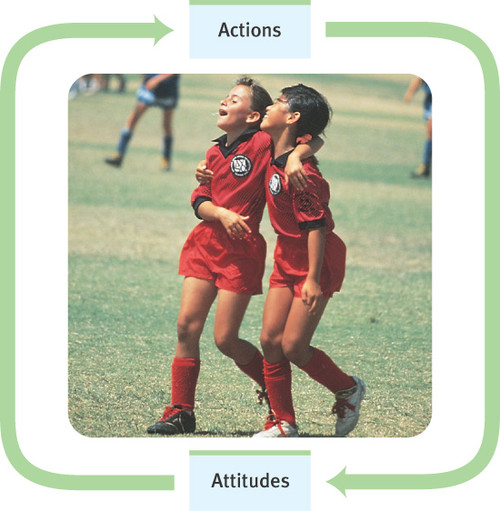

Now consider a more surprising principle: Not only will people sometimes stand up for what they believe, they will also come to believe in the idea they have supported. Many streams of evidence confirm that attitudes follow behavior (Figure 16.1).

16.1.7 The Foot-in-the-Door Phenomenon

Inducing people to act against their beliefs can affect their attitude. During the Korean War, many captured U.S. soldiers were imprisoned in war camps run by Chinese communists. Without using brutality, the captors secured the prisoners’ collaboration in various activities. Some merely ran errands or accepted favors. Others made radio appeals and false confessions. Still others informed on fellow prisoners and divulged military information. When the war ended, 21 prisoners chose to stay with the communists. More returned home “brainwashed”—convinced that communism was a good thing for Asia.

A key ingredient of the Chinese “thought-control” program was its effective use of the foot-in-the-door phenomenon—a tendency for people who agree to a small action to comply later with a larger one. The Chinese began with harmless requests but gradually escalated their demands (Schein, 1956). Having “trained” the prisoners to speak or write trivial statements, the communists then asked them to copy or create something more important—noting, perhaps, the flaws of capitalism. Then, perhaps to gain privileges, the prisoners participated in group discussions, wrote self-criticisms, or uttered public confessions. After doing so, they often adjusted their beliefs toward consistency with their public acts.

The point is simple: To get people to agree to something big, “start small and build,” said Robert Cialdini (1993). Knowing this, you can be wary of those who would exploit you with the tactic. This chicken-and-egg spiral, of actions-feeding-attitudes-feeding-actions, enables behavior to escalate. A trivial act makes the next act easier. Succumb to a temptation and you will find the next temptation harder to resist.

“If the King destroys a man, that’s proof to the King it must have been a bad man.”

Thomas Cromwell, in Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons, 1960

Dozens of experiments have simulated part of the war prisoners’ experience by coaxing people into acting against their attitudes or violating their moral standards. The nearly inevitable result: Doing becomes believing. When people are induced to harm an innocent victim—by making nasty comments or delivering electric shocks—they then begin to disparage their victim. If induced to speak or write on behalf of a position they have qualms about, they begin to believe their own words.

Fortunately, the attitudes-follow-behavior principle works as well for good deeds as for bad. The foot-in-the-door tactic has helped boost charitable contributions, blood donations, and product sales. In one experiment, researchers posing as safe-driving volunteers asked Californians to permit the installation of a large, poorly lettered “Drive Carefully” sign in their front yards. Only 17 percent consented. They approached other home owners with a small request first: Would they display a 3-inch-high “Be a Safe Driver” sign? Nearly all readily agreed. When reapproached two weeks later to allow the large, ugly sign in their front yards, 76 percent consented (Freedman & Fraser, 1966). To secure a big commitment, it often pays to put your foot in the door: Start small and build.

Racial attitudes likewise follow behavior. In the years immediately following the introduction of school desegregation in the United States and the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, White Americans expressed diminishing racial prejudice. And as Americans in different regions came to act more alike—thanks to more uniform national standards against discrimination—they began to think more alike. Experiments confirm the observation: Moral action strengthens moral convictions.

Question 16.2

Write a question that focuses on a key concept in the section you just read, then compose an answer to this question.

+LS3gOJVJp29YZDDrcjjQlH9+Pd6Tv57OzTh89AMk0w7tryEoAfmWi0zaI9xdTPz +JOm5G4OK5HlV1pyreTv1G2GVHHJFZzHko20iZzNoqdRNKI4aiuCkA71TBEyXd41zeEarWv0MsY4QKZAxYUDVQ==16.1.8 Role-Playing Affects Attitudes

“Fake it until you make it.”

Alcoholics Anonymous saying

When you adopt a new role—when you become a college student, marry, or begin a new job—you strive to follow the social prescriptions. At first, your behaviors may feel phony, because you are acting a role. The first weeks in the military feel artificial—as if one is pretending to be a soldier. The first weeks of a marriage may feel like “playing house.” Before long, however, what began as play-acting in the theater of life becomes you.

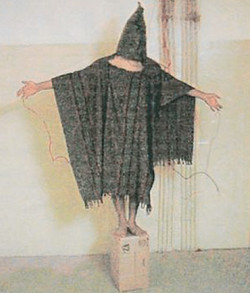

Researchers have confirmed this effect by assessing people’s attitudes before and after they adopt a new role, sometimes in laboratory situations, sometimes in everyday situations, such as before and after taking a job. In one famous laboratory study, male college students volunteered to spend time in a simulated prison devised by psychologist Philip Zimbardo (1972). Some he randomly designated as guards; he gave them uniforms, billy clubs, and whistles and instructed them to enforce certain rules. The remainder became prisoners; they were locked in barren cells and forced to wear humiliating outfits. After a day or two in which the volunteers self-consciously “played” their roles, the simulation became real—too real. Most of the guards developed disparaging attitudes, and some devised cruel and degrading routines. One by one, the prisoners broke down, rebelled, or became passively resigned, causing Zimbardo to call off the study after only six days. More recently, similar situations have played themselves out in the real world—as in Iraq at the Abu Ghraib Prison (see Close-Up: Abu Ghraib Prison: An “Atrocity-Producing Situation”?).

Greece’s military junta during the early 1970s took advantage of the effects of role-playing to train men to become torturers (Staub, 1989). The men’s indoctrination into their roles occurred in small steps. First, the trainee stood guard outside the interrogation cells—the “foot in the door.” Next, he stood guard inside. Only then was he ready to become actively involved in the questioning and torture. As the nineteenth-century writer Nathaniel Hawthorne noted, “No man, for any considerable period, can wear one face to himself and another to the multitude without finally getting bewildered as to which may be true.” What we do, we gradually become.

Regarding President Lyndon Johnson’s commitment to the Vietnam War: “A president who justifies his actions only to the public might be induced to change them. A president who has justified his actions to himself, believing that he has the truth, becomes impervious to self-correction.”

Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson, Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me),2007

Psychologists add a cautionary note: In Zimbardo’s prison simulation, at Abu Ghraib Prison, and in other atrocity-producing situations, some people succumb to the situation and others do not (Carnahan & McFarland, 2007; Haslam & Reicher, 2007; Mastroianni & Reed, 2006;Zimbardo, 2007). Person and situation interact. Water has the power to dissolve some substances, notes John Johnson (2007), but not all. In a watery situation, salt dissolves, sand does not. So also, when put in with rotten apples, some people, but not others, become bad apples.

16.1.9 CLOSE-UP: Abu Ghraib Prison: An “Atrocity-Producing Situation”?

As the first photos emerged in 2004 from Iraq’s Abu Ghraib Prison, the civilized world was shocked. The photos showed U.S. military guards stripping prisoners naked, placing hoods on them, stacking them in piles, prodding them with electricity, taunting them with attack dogs, and subjecting them to sleep deprivation, humiliation, and extreme stress. Was the problem, as so many people initially supposed, a few bad apples—a few irresponsible or sadistic guards? That was the U.S. Army’s seeming verdict when it court-martialed and imprisoned some of the guards, and then cleared four of the five top commanding officers responsible for Abu Ghraib’s policies and operations. The lower-level military guards were “sick bastards,” explained the defense attorney for one of the commanding officers (Tarbert, 2004).

Many social psychologists, however, reminded us that a toxic situation can make even good apples go bad (Fiske et al., 2004). “When ordinary people are put in a novel, evil place, such as most prisons, Situations Win, People Lose,” offered Philip Zimbardo (2004), adding, “That is true for the majority of people in all the relevant social psychological research done over the past 40 years.”

Consider the situation, explained Zimbardo. The guards, some of them model soldier-reservists with no prior criminal or sadistic history, were exhausted from working 12-hour shifts, seven days a week. They were dealing with an enemy, and their prejudices were heightened by fears of lethal attacks and by the violent deaths of many fellow soldiers. They were put in an understaffed guard role, with minimal training and supervision. They were then encouraged to “soften up” for interrogation detainees who had been denied access to the Red Cross. “When you put that set of horrendous work conditions and external factors together, it creates an evil barrel. You could put virtually anybody in it and you’re going to get this kind of evil behavior” (Zimbardo, 2005). Atrocious behaviors often emerge in atrocious situations.

16.1.10 Cognitive Dissonance: Relief From Tension

So far we have seen that actions can affect attitudes, sometimes turning prisoners into collaborators, doubters into believers, mere acquaintances into friends, and compliant guards into abusers. But why? One explanation is that when we become aware that our attitudes and actions don’t coincide, we experience tension, or cognitive dissonance. (I am aware of the threats posed by global climate change, and am aware, with some discomfort, that I often fly in CO2-spewing planes—and thus appreciate airlines that let me reduce my dissonance by purchasing a carbon offset.) To relieve this tension, according to the cognitive dissonance theory proposed by Leon Festinger, we often bring our attitudes into line with our actions. It is as if we rationalize, “If I chose to do it (or say it), I must believe in it.” The less coerced and more responsible we feel for a troubling act, the more dissonance we feel. The more dissonance we feel, the more motivated we are to find consistency, such as changing our attitudes to help justify the act.

The U.S. invasion of Iraq was mainly premised on the presumed threat of Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction (WMD). As the war began, only 38 percent of Americans surveyed said the war was justified even if Iraq did not have WMD (Gallup, 2003). Nearly 80 percent believed such weapons would be found (Duffy, 2003; Newport et al., 2003). When no WMD were found, many Americans felt dissonance, which was heightened by their awareness of the war’s financial and human costs, by scenes of chaos in Iraq, and by inflamed anti-American and pro-terrorist sentiments in some parts of the world.

To reduce dissonance, some people revised their memories of the main rationale for going to war, which then became liberating an oppressed people and promoting democracy in the Middle East. Before long, the once-minority opinion became the majority view: 58 percent of Americans said they supported the war even if there were no WMD (Gallup, 2003). “Whether or not they find weapons of mass destruction doesn’t matter,” explained Republican pollster Frank Luntz (2003), “because the rationale for the war changed.” It was not until late 2004, when hopes for a flourishing peace waned, that Americans’ support for the war dropped below 50 percent.

Dozens of experiments have explored cognitive dissonance by making people feel responsible for behavior that is inconsistent with their attitudes and that has foreseeable consequences. As a subject in one of these experiments, you might agree for a measly $2 to help a researcher by writing an essay that supports something you don’t believe in (perhaps a tuition increase). Feeling responsible for the statements (which are not consistent with your attitudes), you would probably feel dissonance, especially if you thought an administrator would be reading your essay. How could you reduce the uncomfortable dissonance? One way would be to start believing your phony words. Your pretense would become your reality.

The attitudes-follow-behavior principle has a heartening implication: Although we cannot directly control all our feelings, we can influence them by altering our behavior. (Recall from Chapter 12 the emotional effects of facial expressions and of body postures.) If we are down in the dumps, we can do as cognitive therapists advise and talk in more positive, self-accepting ways with fewer self–put-downs. If we are unloving, we can become more loving by behaving as if we were so—by doing thoughtful things, expressing affection, giving affirmation. “Assume a virtue, if you have it not,” says Hamlet to his mother. “For use can almost change the stamp of nature.”

“Sit all day in a moping posture, sigh, and reply to everything with a dismal voice, and your melancholy lingers…. If we wish to conquer undesirable emotional tendencies in ourselves, we must… go through the outward movements of those contrary dispositions which we prefer to cultivate.”

William James, Principles of Psychology, 1890

The point to remember: Cruel acts shape the self. But so do acts of good will. Act as though you like someone, and you soon will. Changing our behavior can change how we think about others and how we feel about ourselves.

Question 16.3

Write a question that focuses on a key concept in the section you just read, then compose an answer to this question.

+LS3gOJVJp29YZDDrcjjQlH9+Pd6Tv57OzTh89AMk0w7tryEoAfmWi0zaI9xdTPz +JOm5G4OK5HlV1pyreTv1G2GVHHJFZzHko20iZzNoqdRNKI4aiuCkA71TBEyXd41zeEarWv0MsY4QKZAxYUDVQ==