Managing Stress Effects

Having a sense of control, nurturing an optimistic outlook, building our social support, and finding meaning can help us experience less stress and thus improve our health. What do we do when we cannot avoid stress? At such times, we need to manage our stress. Aerobic exercise, relaxation, meditation, and active spiritual engagement may help us gather inner strength and lessen stress effects.

Having a sense of control, nurturing an optimistic outlook, building our social support, and finding meaning can help us experience less stress and thus improve our health. What do we do when we cannot avoid stress? At such times, we need to manage our stress. Aerobic exercise, relaxation, meditation, and active spiritual engagement may help us gather inner strength and lessen stress effects.

Aerobic Exercise

10-9 How well does aerobic exercise help manage stress and improve well-being?

It’s hard to find a medicine that works for most people most of the time. But aerobic exercise—sustained activity that increases heart and lung fitness—is one of these rare near-perfect “medicines.” By one estimate, moderate exercise adds not only to your quantity of life—two additional years, on average—but also to your quality of life, with more energy and better mood (Seligman, 1994; Wang et al., 2011).

Alice DeWall

Throughout this book, we have revisited one of psychology’s basic themes: Heredity and environment interact. Physical activity can weaken the influence of genetic risk factors for obesity. In one analysis of 45 studies, that risk fell by 27 percent (Kilpeläinen et al., 2012). Exercise also helps fight heart disease. It strengthens your heart, increases bloodflow, keeps blood vessels open, lowers overall blood pressure, and reduces the hormone and blood pressure reaction to stress (Ford, 2002; Manson, 2002). Compared with inactive adults, people who exercise suffer half as many heart attacks (Powell et al., 1987; Visich & Fletcher, 2009). Exercise makes the muscles hungry for the fats that, if not used by the muscles, contribute to clogged arteries (Barinaga, 1997).

297

Many studies suggest that aerobic exercise reduces stress, depression, and anxiety. For example, half of Americans have reported exercising at least 30 minutes three times a week (Mendes, 2009). People at this level of activity manage stressful situations better, show more self-confidence and energy, and feel less depressed and anxious than their inactive peers (McMurray, 2004; Puetz et al., 2006; Smits et al., 2011). Going from active exerciser to couch potato can increase risk for depression—by 51 percent in two years for the women in one study (Wang et al., 2011). But we could state these observations another way: Stressed and depressed people exercise less. It’s that old correlation problem again—cause and effect are not clear.

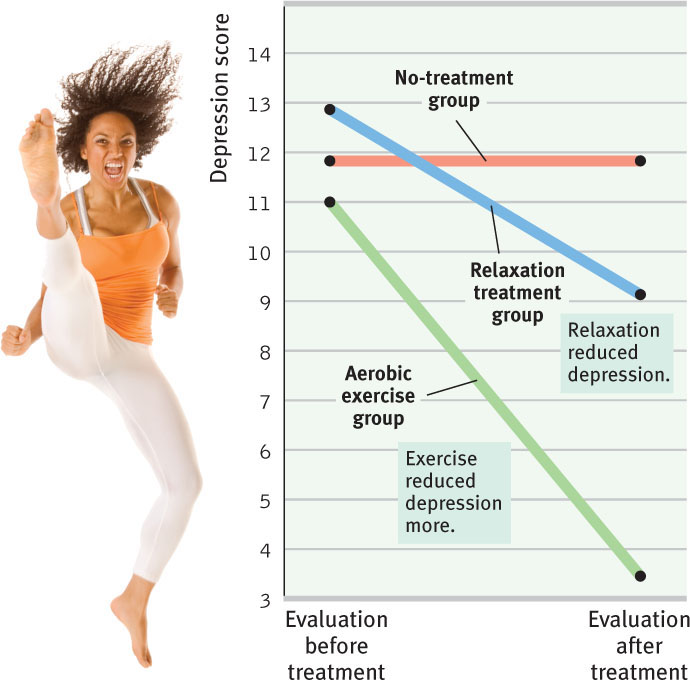

To sort out cause and effect, researchers experiment. They randomly assign people either to an aerobic exercise group or to a control group. Next, they measure whether aerobic exercise (compared with a control activity) produces a change in stress, depression, anxiety, or some other health-related outcome. In one such experiment (McCann & Holmes, 1984), researchers randomly assigned mildly depressed female college students to one of three groups:

- Group 1 completed an aerobic exercise program.

- Group 2 completed a relaxation program.

- Group 3 functioned as a pure control group and did not complete any special activity.

As FIGURE 10.7 shows, 10 weeks later the women in the aerobic exercise program reported the greatest decrease in depression. Many of them had, quite literally, run away from their troubles.

Another experiment randomly assigned depressed people to an exercise group, an antidepressant group, or a placebo pill group. Again, exercise diminished depression levels. And it did so as effectively as antidepressants, with longer-lasting effects (Hoffman et al., 2011). Aerobic exercise counteracts depression in two ways. First, it increases arousal. Second, it does naturally what some prescription drugs do chemically: It increases the brain’s serotonin activity.

More than 150 other studies have confirmed that exercise reduces depression and anxiety. Aerobic exercise has therefore taken a place, along with antidepressant drugs and psychotherapy, on the list of effective treatments for depression and anxiety (Arent et al., 2000; Berger & Motl, 2000; Dunn et al., 2005).

Relaxation and Meditation

10-10 In what ways might relaxation and meditation influence stress and health?

Sit with your back straight, getting as comfortable as you can. Breathe a deep, single breath of air through your nose. Now exhale that air through your mouth as slowly as you can. As you exhale, repeat a focus word, phrase, or prayer—something from your own belief system. Do this five times. Do you feel more relaxed?

298

Why Relaxation Is Good

Like aerobic exercise, relaxation can improve our well-being. Did you notice in Figure 10.7 that women in the relaxation treatment group also experienced reduced depression? More than 60 studies have found that relaxation procedures can also provide relief from headaches, high blood pressure, anxiety, and insomnia (Nestoriuc et al., 2008; Stetter & Kupper, 2002).

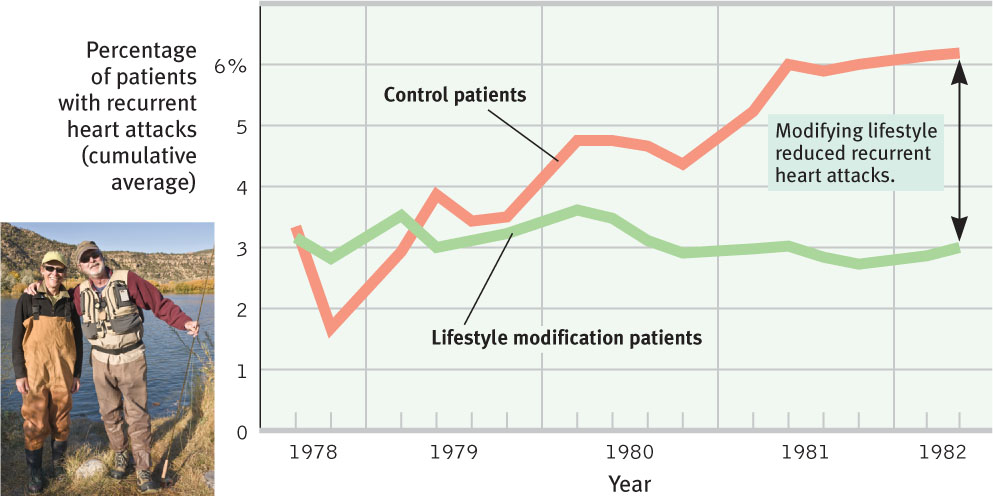

Researchers have even used relaxation to help Type A heart attack survivors reduce their risk of future attacks (Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). They randomly assigned hundreds of these middle-aged men to one of two groups. The first group received standard advice from cardiologists about medications, diet, and exercise habits. The second group received similar advice, but they also were taught ways of modifying their lifestyle. They learned to slow down and relax by walking, talking, and eating more slowly. They learned to smile at others and laugh at themselves. They learned to admit their mistakes, to take time to enjoy life, and to renew their religious faith. The training paid off spectacularly (FIGURE 10.8). During the next three years, the lifestyle modification group had half as many repeat heart attacks as did the first group. A British study supported this finding. Lifestyle modification cut the risk of heart attack in half over 13 years for heart-attack-prone people (Eysenck & Grossarth-Maticek, 1991).

Time may heal all wounds, but relaxation can help speed that process. In one study, surgery patients were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups received standard treatment, but the second group also experienced a 45-minute relaxation exercise and received relaxation recordings to use before and after surgery. A week after surgery, patients in the second group reported lower stress and showed better wound healing (Broadbent el al., 2012).

Learning to Reflect and Accept

Meditation is a modern practice with a long history in a variety of world religions. Meditation was originally used to reduce suffering and improve awareness, insight, and compassion. Today, it has found a new home in stress management programs, such as mindfulness meditation. If you were taught this practice, you would relax and silently attend to your inner state, without judging it (Kabat-Zinn, 2001). You would sit down, close your eyes, and mentally scan your body from head to toe. Zooming your focus on certain body parts and responses, you would remain aware and accepting. You would also pay attention to your breathing, attending to each breath as if it were a material object.

299

Practicing mindfulness may improve many health measures. One study analyzed 39 experiences, involving 1140 people. Some received mindfulness-based therapy for several weeks. Others did not. Levels of anxiety and depression were lower among those who received the therapy (Hofmann et al., 2010). In another study, mindfulness training improved immune system functioning and coping in a group of women newly diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer (Witek-Janusek et al., 2008). Mindfulness practices have also been linked with improvements in other areas, including reducing sleep problems, cigarette use, binge eating, and alcohol and other substance abuse (Bowen et al., 2006; Brewer et al., 2011; Cincotta et al., 2011; de Dios et al., 2012; Kristeller et al., 2006).

So, what’s going on in the brain as we practice mindfulness? Correlational and experimental studies offer three explanations for how mindfulness helps us make positive changes:

- It strengthens connections among regions in our brain. The affected regions are those associated with focusing our attention, processing what we see and hear, and being reflective and aware (Ives-Deliperi et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2011).

- It activates brain regions associated with more reflective awareness (Davidson et al., 2003; Way et al., 2010). When labeling emotions, “mindful people” show less activation in the amygdala, a brain region associated with fear, and more activation in the prefrontal cortex, which aids emotion regulation (Creswell et al., 2007).

- It calms brain activation in emotional situations. This lower activation was clear in one study in which participants watched two movies—one sad, one neutral. Those in the control group, who were not trained in mindfulness, showed strong differences in brain activation when watching the two movies. Those who had received mindfulness training showed little change in brain response to the two movies (Farb et al., 2010). Emotionally unpleasant images also trigger weaker electrical brain responses in mindful people than in their less mindful counterparts (Brown et al., 2013). A mindful brain is strong, reflective, and soothing.

Exercise and meditation are not the only routes to healthy relaxation. Massage helps relax both premature infants (Chapter 3) and those suffering pain (Chapter 5). An analysis of 17 experiments revealed another benefit: Massage therapy relaxes muscles and helps reduce depression (Hou et al., 2010).

Faith Communities and Health

10-11 Does religious involvement relate to health?

A wealth of studies has revealed another curious correlation, called the faith factor. Religiously active people tend to live longer than those who are not religiously active. In one 16-year study, researchers tracked 3900 Israelis living in one of two groups of communities (Kark et al., 1996). The first group contained 11 religiously orthodox collective settlements. The second group contained 11 matched, nonreligious collective settlements. The researchers found that “belonging to a religious collective was associated with a strong protective effect” not explained by age or economic differences. In every age group, religious community members were about half as likely to have died as were those in the nonreligious community.

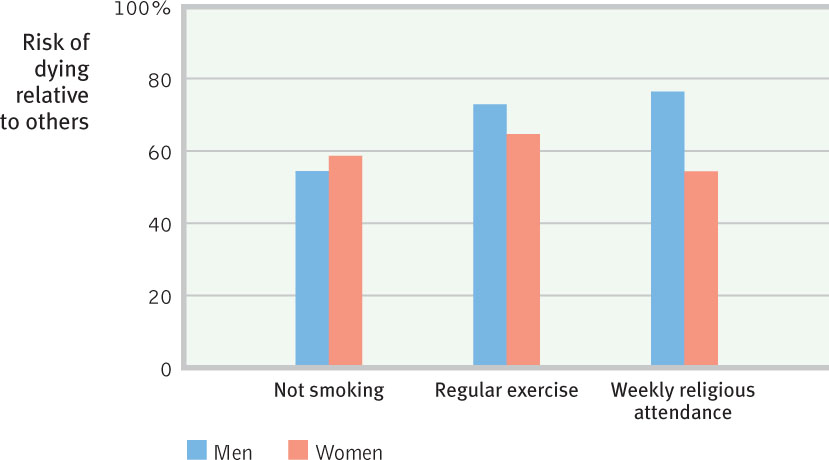

How should we interpret such findings? Remember that correlation does not mean causation. What other factors might explain these protective effects? Here’s one possibility: Women are more religiously active than men, and women outlive men. Does religious involvement reflect this gender-longevity link? No. Although the spirituality-longevity correlation is stronger among women, it also appears among men (McCullough et al., 2000, 2005). In study after study—some lasting 28 years, and some studying more than 20,000 people—the faith factor holds (Chida et al., 2009; Hummer et al., 1999; Schnall et al., 2010). And it holds after researchers control for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education, and region. In one study, this effect translated into a life expectancy at age 20 of 83 years for attenders at religious services (more than weekly) and only 75 years for nonattenders (FIGURE 10.9).

Does this mean that nonattenders who start attending services and change nothing else will live longer? Again, the answer is No. But we can say that religious involvement predicts health and longevity, just as nonsmoking and exercise do. Religiously active people have demonstrated healthier immune functioning, fewer hospital admissions, and, for AIDS patients, fewer stress hormones and longer survival (Ironson et al., 2002; Koenig & Larson, 1998; Lutgendorf et al., 2004).

300

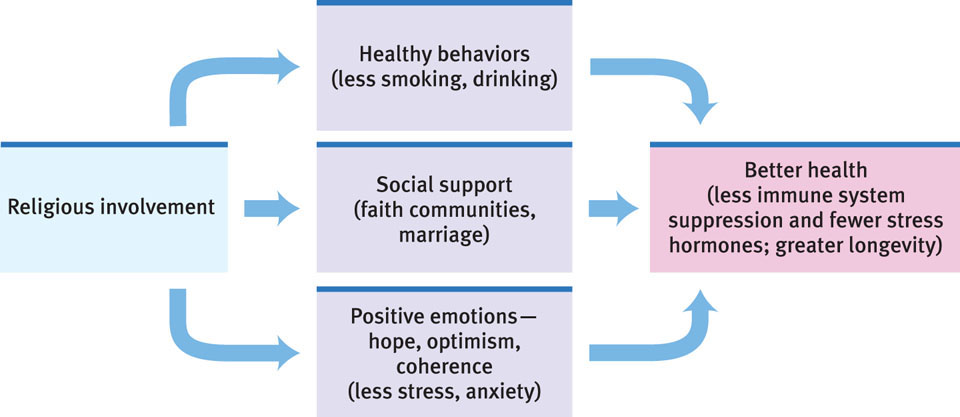

Can you imagine why religiously active people might be healthier and live longer than others? Here are three factors that help explain the correlation:

- Healthy lifestyles Religiously active people have healthier lifestyles. For example, they smoke and drink less (Islam & Johnson, 2003; Koenig & Vaillant, 2009; Koopmans et al., 1999). In one Gallup survey of 550,000 Americans, 15 percent of the very religious were smokers, compared with 28 percent of nonreligious people (Newport et al., 2010). But healthy lifestyles are not the complete answer. In studies that have controlled for unhealthy behaviors, such as inactivity and smoking, about 75 percent of the life-span difference remained (Musick et al., 1999).

- Social support Those who belong to a faith community have access to a support network. When misfortune strikes, religiously active people can turn to each other for support. Moreover, religions encourage marriage, another predictor of health and longevity. In the Israeli religious settlements, for example, divorce has been almost nonexistent. But even after controlling for social support, gender, unhealthy behaviors, and preexisting health problems, much of the original religious engagement correlation remains (Chida et al., 2009; George et al., 2000; Powell et al., 2003).

- Positive emotions Researchers speculate that a third set of influences help protect religiously active people from stress and enhance their well-being (FIGURE 10.10). Religiously active people have a stable worldview, a sense of hope for the long-term future, and feelings of ultimate acceptance. They may also benefit from the relaxed meditation of prayer or Sabbath observance. Taken together, these positive emotions and expectations may have a protective effect on well-being.

FIGURE 10.10 Possible explanations for the correlation between religious involvement and health/longevity

FIGURE 10.10 Possible explanations for the correlation between religious involvement and health/longevity

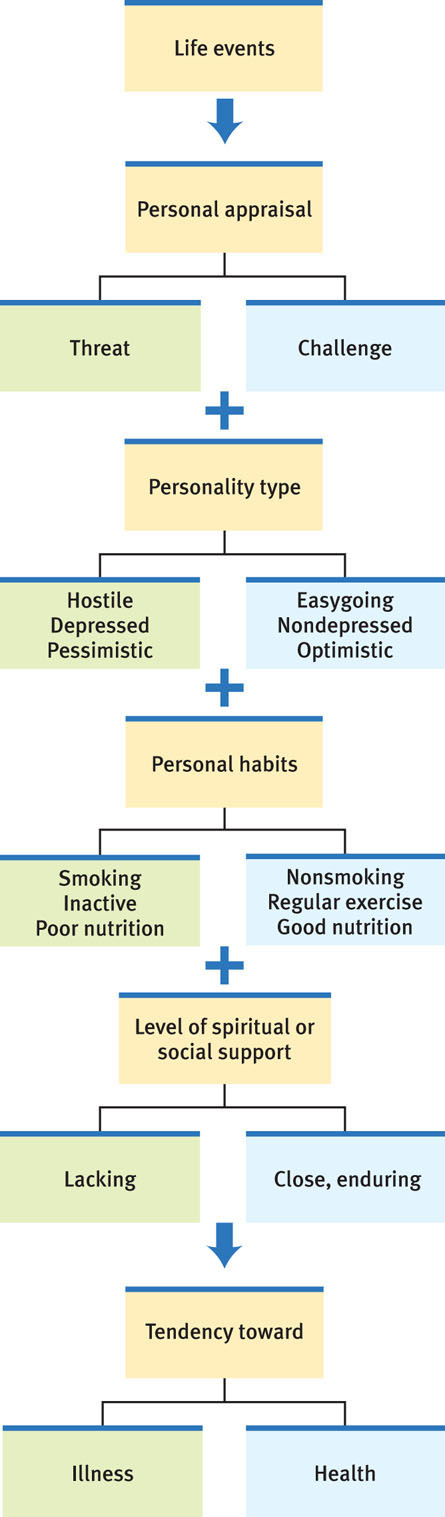

Let’s summarize what we’ve learned so far: Sustained emotional reactions to stressful events can be damaging. However, some qualities and influences can help us cope with life’s challenges by making us emotionally and physically stronger. These include a sense of control, an optimistic outlook, relaxation, healthy habits, social support, a sense of meaning, and spirituality (FIGURE 10.11).

In the remainder of this chapter, we’ll take a closer look at our pursuit of happiness and how it relates to our human flourishing.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 10.6

What are some of the tactics that help people manage the stress they cannot avoid?

Aerobic exercise, relaxation procedures, mindfulness meditation, and religious engagement

301