Trait Theories

11-12 How do psychologists use traits to describe personality?

Freudian and humanistic theories shared a common goal: Explain how our personality develops. They focused on the forces that act upon us. Trait researchers, led by the work of Gordon Allport (1897–1967), have been less concerned with explaining traits than with describing them. They define personality as a stable and enduring pattern of behavior, such as Lady Gaga’s consistent sociability, openness to new experiences, and self-discipline. These three traits help describe her personality.

Freudian and humanistic theories shared a common goal: Explain how our personality develops. They focused on the forces that act upon us. Trait researchers, led by the work of Gordon Allport (1897–1967), have been less concerned with explaining traits than with describing them. They define personality as a stable and enduring pattern of behavior, such as Lady Gaga’s consistent sociability, openness to new experiences, and self-discipline. These three traits help describe her personality.

Exploring Traits

Imagine that you’ve been hired by an Internet dating service. Your job is to construct a questionnaire that will help people describe themselves to those seeking dates and mates. With millions of people using such services each year, the need to understand and incorporate psychological science grows more important (Finkel et al, 2012a,b). What personality traits might give an accurate sense of the person filling out the questionnaire? You might begin by thinking of how we describe a pizza. We place it along several trait dimensions. It’s small, medium, or large; it has one or more toppings; it has a thin or thick crust. By likewise placing people on trait dimensions, we can begin to describe them.

Basic Factors

An even better way to identify our personality is to identify factors —clusters of behavior tendencies that occur together. People who describe themselves as outgoing, for example, may also say that they like excitement and practical jokes and dislike quiet reading. This cluster of behaviors reflects a basic factor, or trait—in this case, extraversion. (For more about extraversion’s opposite, see Thinking Critically About: The Stigma of Introversion.)

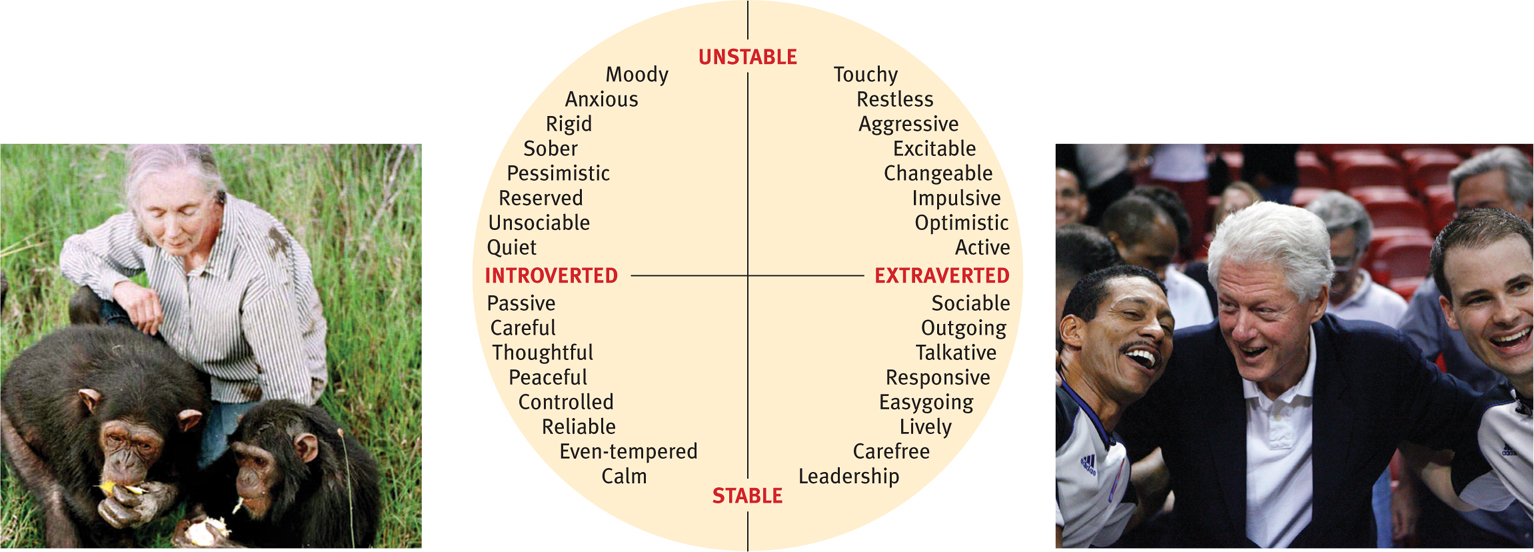

So how many traits will be just the right number for your Internet dating questionnaire? If psychologists Hans Eysenck and Sybil Eysenck [EYE-zink] had been hired to do your job, they would have said two. They believed that we can reduce many normal human variations to two basic factors: Extraversion–introversion and emotional stability–instability (FIGURE 11.3). People in 35 countries, from China to Uganda to Russia, have taken the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire. The extraversion and emotionality factors emerged as basic personality dimensions (Eysenck, 1990, 1992).

Andrew Innerarity/REUTERS

323

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

The Stigma of Introversion

Psychologists describe personality, but they don’t advise which traits people should or should not have. Society does this. Western cultures prize extraversion more than all personality traits. Being introverted means that you don’t have the “right stuff” (Cain, 2012).

Our superheroes have extraverted personalities. Extraverted Superman is bold and energetic. His introverted alter ego, Clark Kent, is mild-mannered and writes for a living. The message is clear: To show people you’re a superhero, show them you’re an extravert.

TV shows also portray heartthrobs and examples of success as extraverts. Donald Draper, the highly successful, attractive advertising executive in the hit show Mad Men is a classic extravert. He is dominant and charismatic. Women clamor for his attention. Again, the message is plain: Extraversion equals success, and introversion doesn’t.

Why does our culture celebrate extraversion and belittle introversion? Many people may not understand what introversion really is. People tend to equate introversion with shyness, but the two concepts are quite different. Introverted people seek low levels of stimulation from their environment because they’re very sensitive. One classic study suggested that introverted people even have greater taste sensitivity. When given lemon juice, introverted people salivated more than extraverted people (Corcoran, 1964). Shy people, in contrast, remain quiet because they fear others will evaluate them negatively.

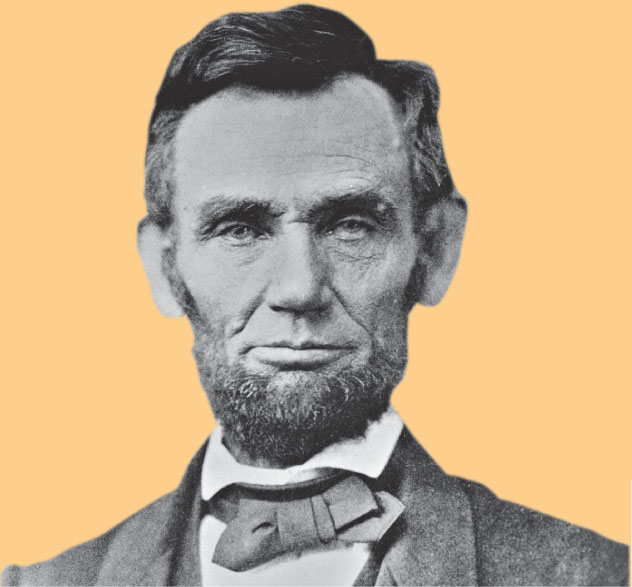

People may also believe that introversion acts as a barrier to success. On the contrary, introverts experience tremendous achievement. They show greater receptiveness when their employees voice their ideas, challenge existing norms, and take charge. Under these circumstances, introverted leaders outperform extraverted ones (Grant et al., 2011). Perhaps the best example of the misperception that introversion hinders career success lies in the American presidency. The American president who is most consistently ranked number one of all time was introverted. His name was Abraham Lincoln.

So, introversion should not be a sign of disgrace. Those who need a quiet break from a loud party are not broken, unacceptable, or incapable of great things. They simply know how to pick an environment where they can thrive. It’s important for extraverts to understand that not everyone needs the high levels of stimulation that they do. It’s not a crime to unwind.

Biology and Personality

As you may recall from the twin and adoption studies discussed in Chapter 3, our genes have much to say about the temperament and behavioral style that help define our personality. Children’s shyness, for example, seems related to differences in their autonomic nervous systems. Infants with reactive autonomic nervous systems respond to stress with greater anxiety and inhibition (Kagan, 2010).

Brain activity appears to vary with personality as well. Brain-activity scans suggest that extraverts seek stimulation because their normal brain arousal is relatively low. Also, a frontal lobe area involved in restraining behavior is less active in extraverts than in introverts (Johnson et al., 1999).

Personality differences among dogs are as obvious to researchers as they are to dog owners. Such differences (in energy, affection, reactivity, and curious intelligence) are as evident, and as consistently judged, as personality differences among humans (Gosling et al., 2003; Jones & Gosling, 2005). Monkeys, chimpanzees, orangutans, and even birds also have stable personalities (Weiss et al., 2006). Among the Great Tit (a European relative of the American chickadee), bold birds more quickly inspect new objects and explore trees (Groothuis & Carere, 2005; Verbeek et al., 1994). By selective breeding, researchers can produce bold or shy birds. Both have their place in natural history. In lean years, bold birds are more likely to find food; in abundant years, shy birds feed with less risk.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.8

Which two primary dimensions did Hans and Sybil Eysenck propose for describing personality variation?

introversion–extraversion and emotional stability–instability

324

Assessing Traits

11-13 What are personality inventories?

It helps to know that a potential date is an introvert or an extravert, or even that the person is emotionally stable or unstable. But wouldn’t you like more information about the test-taker’s personality before matching people as romantic partners? The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) might help. Personality inventories, including the famous MMPI, are long sets of questions covering a wide range of feelings and behaviors. Although the MMPI was originally developed to identify emotional disorders, it also assesses people’s personality traits. Unlike projective tests such as the Rorschach, personality inventories are scored objectively—so objectively that a computer can administer and score them. Objectivity does not, however, guarantee validity. People taking the MMPI for employment purposes can give the answers they know will create a good impression. But in so doing they may also score high on a lie scale that assesses faking (as when people respond False to a universally true statement, such as “I get angry sometimes”). The objectivity of the MMPI has contributed to its popularity and to its translation into more than 100 languages.

The Big Five Factors

11-14 Which traits seem to provide the most useful information about personality variation?

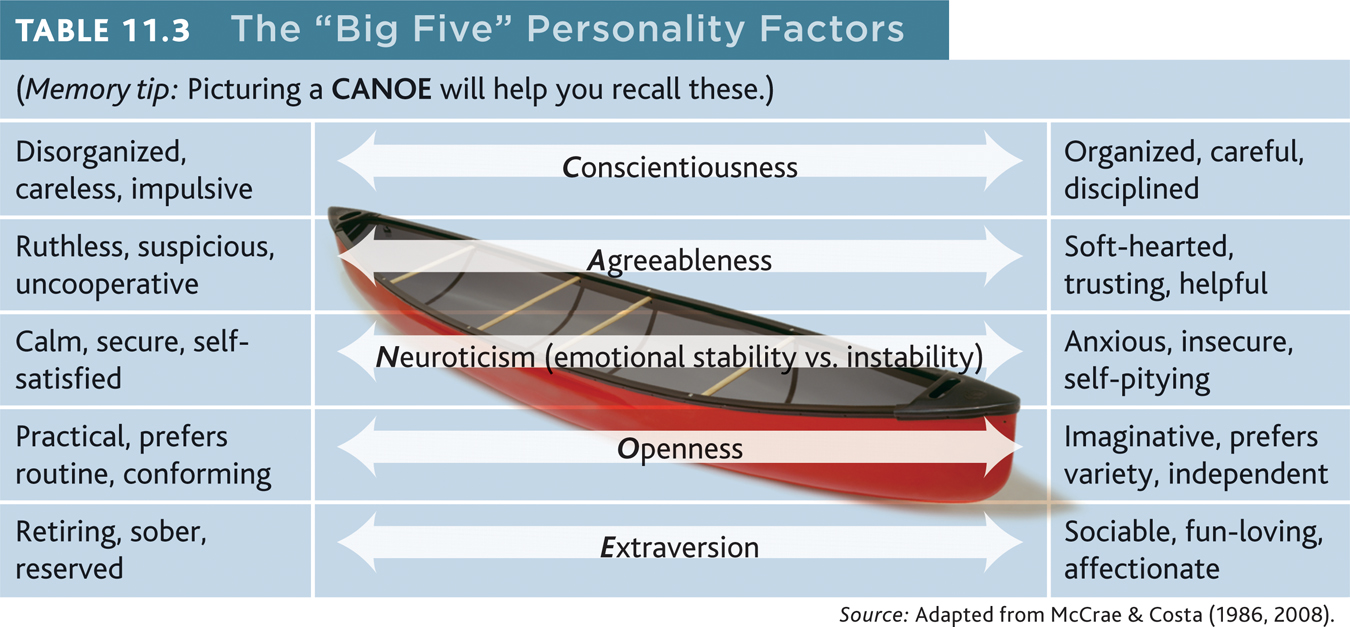

Today’s trait researchers rely on five factors (called the Big Five) to understand personality—conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness, and extraversion (TABLE 11.3) (Costa & McCrae, 2011; John & Srivastava, 1999). Work by Paul Costa, Robert McCrae, and others shows that where we fall on these five dimensions reveals much of what there is to say about our personality.

As the dominant model in personality psychology, Big Five research has explored various questions:

- How stable are these traits? One research team analyzed 1.25 million participants ages 10 to 65. They learned that personality continues to develop and change through late childhood and adolescence. By adulthood, our traits have become fairly stable, though conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness, and extraversion continue to increase over the life span, and neuroticism (emotional instability) decreases (Soto et al., 2011). Some other dimensions of the Big Five (in addition to neuroticism) decrease as people become older (Lucas & Donnellan, 2011).

- Have these traits changed over time? Cultures change over time, which can influence shifts in personality. Within the United States and the Netherlands, extraversion and conscientiousness have increased over time (Mroczek & Spiro, 2003; Smits et al., 2011; Twenge, 2001).

- Do we inherit these traits? Roughly 50 percent of our individual differences on the Big Five can be credited to our genes (Jang et al., 2006; Krueger & Johnson, 2008; Loehlin et al., 1998).

- Do these traits reflect differing brain structure or function? The size of different brain regions does correlate with several Big Five traits (DeYoung et al., 2010). For example, those who score high on conscientiousness tend to have a larger frontal lobe area that aids in planning and controlling behavior. Brain connections also influence the Big Five traits (Adelstein et al., 2011). For example, people high in openness have brains that are wired to experience intense imagination, curiosity, and fantasy.

- How well do these traits apply to various cultures? The Big Five dimensions describe personality in various cultures reasonably well (Schmitt et al., 2007; Yamagata et al., 2006). “Features of personality traits are common to all human groups,” concluded Robert McCrae and 79 co-researchers (2005) from their 50-culture study.

- Do the Big Five traits predict our actual behavior? Yes. For example, our traits appear in our language patterns. In blog posts, extraversion predicts use of personal pronouns (we, our, us). Agreeableness predicts positive-emotion words. Neuroticism predicts negative-emotion words (Yarkoni, 2010).

If you work the Big Five traits into your dating questionnaire, your mission should be accomplished—assuming people act the same way at all times and in all situations. Next, we ask, do they?

325

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.9

What are the Big Five personality factors, and why are they scientifically useful?

The Big Five personality factors are conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism (emotional stability vs. instability), openness, and extraversion (CANOE). These factors may be objectively measured, and research suggests that these factors are relatively stable across the life span and apply to all cultures in which they have been studied.

Evaluating Trait Theories

11-15 Does research support the consistency of personality traits over time and across situations?

To be useful indicators of personality, traits would have to persist over time and across situations. Friendly people, for example, would have to act friendly at different times and places. In some ways, our personality seems stable. Cheerful, friendly children tend to become cheerful, friendly adults. But it’s also true that a fun-loving jokester can suddenly be serious and respectful at a job interview. The personality traits we express change from one situation to another.

The Person-Situation Controversy

Many researchers have studied personality stability over the life span. A group of 152 long-term studies compared early trait scores with scores for the same traits seven years later. These comparisons were done for several different age groups, and for each group, the scores were positively correlated. But the correlations were strongest for comparisons done in adulthood. For young children, the correlation between early and later scores was +0.3. For collegians, the correlation was +0.54. For 70-year-olds, the correlation was +0.73. (Remember that 0 indicates no relationship, and +1.0 would mean that one score perfectly predicts the other.)

As we grow older, our personality traits stabilize. Interests may change—the devoted collector of tropical fish may become the devoted gardener. Careers may change—the determined salesperson may become a determined social worker. Relationships may change—the hostile spouse may start over with a new partner. But most people recognize their traits as their own.

The consistency of specific behaviors from one situation to the next is another matter. People are not always predictable. What relationship would you expect to find between a student’s being conscientious on one occasion (say, showing up for class on time) and being conscientious on another occasion (say, turning in assignments on time)? If you’ve noticed how outgoing you are in some situations and how reserved you are in others, perhaps you said, “very little.” That’s what researchers have found—only a small correlation (Mischel, 1968, 1984, 2004). This inconsistency makes personality traits weak predictors of behaviors. Personality traits predict a person’s behavior across many different situations. They do not neatly predict a person’s behavior in any one specific situation (Mischel, 1968, 1984; Mischel & Shoda, 1995).

If we remember such results, we will be more careful about labeling other people (Mischel, 1968, 2004). We will recognize how difficult it is to predict whether someone is likely to violate parole, commit suicide, or be an effective employee. Years in advance, science can tell us the distance of the Earth from the Sun for any given date. A day in advance, meteorologists can often predict the weather. Yet psychologists have not yet solved the riddle of how you will feel and act tomorrow, or even a few hours from now.

Does this mean that psychological science has nothing meaningful to say about personality traits? No! Remember that traits do a good job at predicting people’s average behavior (outgoingness, happiness, carelessness) over many situations (Epstein, 1983a,b).

Even when we try to restrain them, our traits may assert themselves. During my [DM] noontime pickup basketball games with friends, I keep vowing to cut back on my jabbering and joking. But without fail, the irrepressible chatterbox reoccupies my body moments later. I [ND] have a similar experience each time I try to stay quiet when riding in taxis, but somehow always end up chatting!

Our personality traits lurk in some unexpected places.

326

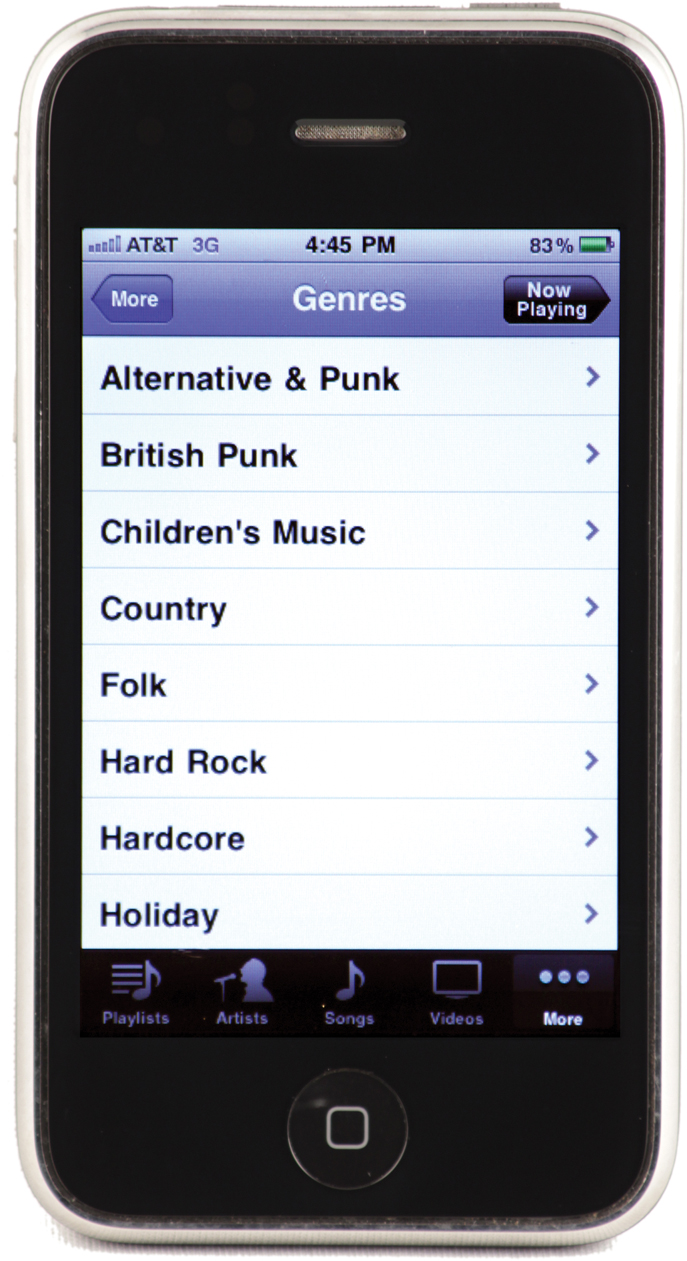

- Music preferences: Your playlist says a lot about who you are. Classical, jazz, blues, and folk music lovers tend to be open to experience and verbally intelligent. Extraverts tend to prefer upbeat and energetic music. Country, pop, and religious music lovers tend to be cheerful, outgoing, and conscientious (Langmeyer et al., 2012; Rentfrow & Gosling, 2003).

- Bedrooms and offices: Our personal spaces—our scattered papers or neat surfaces—display our personality. After just a few minutes’ inspection of someone’s living and working spaces, you could give a fairly accurate summary of their conscientiousness, openness to new experience, and even emotional stability (Gosling, 2008).

- Electronic communications: Have you ever felt you could detect others’ personality from their writing voice? You are right!! What a cool, exciting finding!!! (If you catch my drift.) You can predict levels of extraversion, neuroticism, and agreeableness by analyzing the content of a person’s last 20 texts (Holtgraves, 2011). For example, those who score high in extraversion draw attention to themselves by using more first-person singular pronouns (for example, “I” and “me”). Those high in neuroticism use more negative emotion words. And those high in agreeableness use fewer swear words. You can also gauge a person’s extraversion and neuroticism by reading their e-mails (Gill et al., 2006; Oberlander & Gill, 2006).

- Social networking sites: Online profiles and personal websites are a canvas for self-expression. They offer clues to a person’s extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness (Back et al., 2010). Even mere photos, with their associated clothes, expressions, and postures, can give clues to personality (Naumann et al., 2009).

In unfamiliar, formal situations—perhaps as a guest in the home of a person from another culture—our traits remain hidden as we carefully attend to social cues. In familiar, informal situations—just hanging out with friends—we feel more relaxed, and our traits emerge (Buss, 1989). In these informal situations, our expressive styles—our animation, manner of speaking, and gestures—are impressively consistent. Viewing “thin slices” of someone’s behavior—such as seeing a photo for a mere fraction of a second or seeing three 2-second video clips of a teacher in action—can tell us a lot about the person’s basic personality traits (Ambady, 2010; Rule et al., 2009).

To sum up, we can say that the immediate situation powerfully influences our behavior, especially when the situation makes clear demands (Cooper & Withey, 2009). We can better predict drivers’ behavior at traffic lights from knowing the color of the lights than from knowing the drivers’ personalities. Averaging our behavior across many occasions does, however, reveal distinct personality traits. Traits exist, and they leave tracks in our lives. We differ. And our differences matter.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 11.10

How well do personality test scores predict our behavior? Explain.

Our scores on personality tests predict our average behavior across many situations much better than they predict our specific behavior in any given situation.