Anxiety Disorders, OCD, and PTSD

13-5 What are the main anxiety disorders, and how do anxiety disorders differ from the ordinary worries and fears we all experience?

Anxiety is part of life. Have you ever felt anxious when speaking in front of a class, peering down from a high ledge, or waiting to play in a big game? We all feel anxious at times. We may occasionally feel enough anxiety to avoid making eye contact or talking with someone—“shyness,” we call it. Fortunately for most of us, our uneasiness is not intense and persistent.

Anxiety is part of life. Have you ever felt anxious when speaking in front of a class, peering down from a high ledge, or waiting to play in a big game? We all feel anxious at times. We may occasionally feel enough anxiety to avoid making eye contact or talking with someone—“shyness,” we call it. Fortunately for most of us, our uneasiness is not intense and persistent.

Some of us, however, are especially prone to notice and remember threats (Mitte, 2008). This tendency may place us at risk for one of the anxiety disorders, marked by distressing, persistent anxiety or by maladaptive behaviors that reduce anxiety. For example, a man with a fear of social settings may avoid going out. This behavior is maladaptive because it reduces his anxiety but does not help him cope with his world.

In this section we focus on three anxiety disorders:

- Generalized anxiety disorder, in which a person is constantly tense and uneasy for no apparent reason.

- Panic disorder, in which a person experiences sudden episodes of intense dread and often lives in fear of when the next attack might strike.

- Phobias, in which a person feels irrationally and intensely afraid of a specific object or situation.

Two other disorders involve anxiety, though the DSM-5 now classifies them separately:

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder, in which a person is troubled by repetitive thoughts or actions.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder, in which a person has lingering memories, nightmares, and other symptoms for weeks after a severely threatening, uncontrollable event.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Tom is a 27-year-old electrician. For the past two years, he has been bothered by dizziness, sweating palms, irregular heartbeat, and ringing in his ears. He feels on edge and sometimes finds himself shaking. Tom has been fairly successful at hiding his symptoms from his family and co-workers, but sometimes he has to leave work. He allows himself few other social contacts. Neither his family doctor nor a neurologist has been able to find any physical problem.

377

Tom’s restless, unfocused, out-of-control, and agitated feelings suggest generalized anxiety disorder. The symptoms of this disorder are commonplace; their persistence is not. People with this condition worry continually, and they are often jittery, on edge, and sleep deprived. Concentration is difficult, as attention switches from worry to worry. Their tension may leak out through furrowed brows, twitching eyelids, trembling, sweating, or fidgeting.

The person may not be able to identify and therefore relieve or avoid the tension’s cause. To use Sigmund Freud’s term, the anxiety is free-floating (not linked with a specific stressor or threat). Generalized anxiety disorder and depression often go hand in hand, but even without depression this disorder tends to be disabling (Hunt et al., 2004; Moffitt et al., 2007b). Moreover, it may lead to physical problems, such as high blood pressure.

Two-thirds of those with generalized anxiety disorder are women. The anxiety gender difference appeared in a Gallup poll taken eight months after 9/11. More U.S. women (34 percent) than men (19 percent) said they were still less willing than before 9/11 to go into skyscrapers or fly on planes. And in early 2003, more women (57 percent) than men (36 percent) said they were “somewhat worried” about becoming a terrorist victim (Jones, 2003).

Some people with generalized anxiety disorder were treated badly and felt inhibited when they were children (Moffitt et al., 2007a). As time passes, emotions tend to mellow. By age 50, generalized anxiety disorder becomes rare (Rubio & López-Ibor, 2007).

Panic Disorder

In panic disorder, anxiety suddenly escalates into a terrifying panic attack—a minutes-long feeling of intense fear that something horrible is about to happen. Irregular heartbeat, chest pains, shortness of breath, choking, trembling, or dizziness may accompany the fear. One woman recalled suddenly feeling “hot and as though I couldn’t breathe. My heart was racing and I started to sweat and tremble and I was sure I was going to faint. Then my fingers started to feel numb and tingly and things seemed unreal. It was so bad I wondered if I was dying and asked my husband to take me to the emergency room. By the time we got there (about 10 minutes) the worst of the attack was over and I just felt washed out” (Greist et al., 1986). This anxiety tornado strikes suddenly, does its damage, and disappears, but it is not forgotten. After experiencing even a few panic attacks, people may come to fear the fear itself.

Those having (or observing) a panic attack often misread the symptoms as an impending heart attack or other serious physical ailment. Smokers have at least a doubled risk of a panic attack (Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005). Because nicotine is a stimulant, lighting up doesn’t lighten up.

Phobias

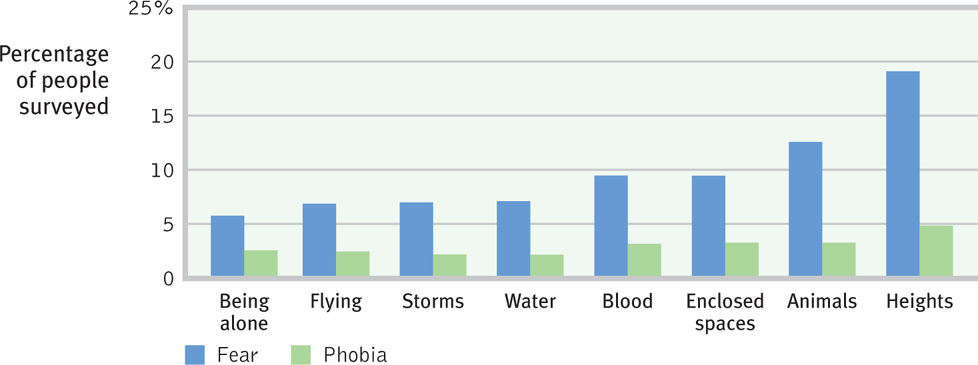

We all live with some fears. People with phobias are consumed by a persistent, irrational fear and avoidance of some object or situation. Marilyn, an otherwise healthy and happy 28-year-old, so fears thunderstorms that she feels anxious as soon as a weather forecast mentions possible storms later in the week. If her husband is away and a storm is forecast, she may stay with a close relative. During a storm, she hides from windows and buries her head to avoid seeing the lightning. Specific phobias such as Marilyn’s typically focus on particular animals, insects, heights, blood, or enclosed spaces (FIGURE 13.1).

378

Not all phobias are so specific. The constant fear of having another panic attack can lead people with panic disorder to avoid situations where panic might strike. Their avoidance itself may lead to a diagnosis of agoraphobia, the fear of again experiencing the dreaded tornado of anxiety. The fear of being unable to escape or get help during an attack may cause people with agoraphobia to avoid being outside the home, in a crowd, or on a bus. Those with social anxiety disorder (formerly called social phobia) may also avoid going out, but for different reasons. Their intense fear of being judged by others may cause them to avoid social situations such as speaking up, eating out, or going to parties, or they may sweat or tremble when doing so.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.4

Unfocused tension, apprehension, and arousal is called __________ __________ disorder. If a person is focusing anxiety on specific feared objects or situations, that person may have a __________. Those who experience unpredictable periods of terror and intense dread, accompanied by frightening physical sensations, may be diagnosed with a __________ disorder.

generalized anxiety; phobia; panic.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

13-6 What is OCD?

As with generalized anxiety and phobias, we can see aspects of our own behavior in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Obsessive thoughts (recall Marc’s focus on cleaning his room) are unwanted and so repetitive it may seem they will never go away. Compulsive behaviors are responses to those thoughts (cleaning and cleaning and cleaning).

All of us are at times obsessed with senseless or offensive thoughts that will not go away. Have you ever caught yourself behaving compulsively, perhaps rigidly checking, ordering, and cleaning before guests arrive, or lining up books and pencils “just so” before you begin studying? On a small scale, obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors are part of everyday life. They cross the fine line between normality and disorder when they interfere with everyday life and cause us distress. Checking to see if you locked the door is normal; checking 10 times is not. Washing your hands is normal; washing so often that your skin becomes raw is not. Normal rehearsals and fussy behaviors become a disorder when the obsessive thoughts are so haunting, the compulsive rituals so senselessly time-consuming, that effective functioning becomes impossible.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

13-7 What is PTSD?

As an Iraq war soldier, Jesse “saw the murder of children and women. It was just horrible for anyone to experience.” After calling in a helicopter strike on one house where he had seen ammunition crates carried in, he heard the screams of children from within. “I didn’t know there were kids there,” he recalled. Back home in Texas, he suffered “real bad flashbacks” (Welch, 2005).

Jesse is not alone. In one study of 103,788 veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, 25 percent were diagnosed with a psychological disorder (Seal et al., 2007). The most frequent diagnosis was posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Typical symptoms include recurring haunting memories and nightmares, a numb feeling of social withdrawal, jumpy anxiety, and trouble sleeping (Hoge et al., 2004, 2006, 2007; Kessler, 2000). Many battle-scarred veterans have been diagnosed with PTSD. Survivors of accidents, disasters, and violent and sexual assaults (including an estimated two-thirds of prostitutes) have also experienced these symptoms (Brewin et al., 1999; Farley et al., 1998; Taylor et al., 1998).

379

The greater one’s emotional distress during a trauma, the higher the risk for posttraumatic symptoms (Ozer et al., 2003). Among American military personnel in Afghanistan, 7.6 percent of combatants and 1.4 percent of noncombatants developed PTSD (McNally, 2012). Among New Yorkers who witnessed or responded to the 9/11 terrorist attacks, most did not experience PTSD (Neria et al., 2011). After experiencing a traumatic life event, about 5 to 10 percent of people develop PTSD (Bonanno et al., 2011). PTSD diagnoses among survivors who had been inside the World Trade Center during the attack were, however, double the rates found among those who were outside (Bonanno et al., 2006).

A $125 million, five-year U.S. Army program is currently assessing the well-being of 800,000 soldiers and training them in emotional resilience (Stix, 2011).

About half of us will experience at least one traumatic event in our lifetime. Why do some people develop PTSD after a traumatic event, but others don’t? Some people may have more sensitive emotion-processing limbic systems that flood their bodies with stress hormones (Kosslyn, 2005; Ozer & Weiss, 2004). The odds of getting this disorder after a traumatic event are higher for women (about 1 in 10) than for men (1 in 20) (Olff et al., 2007; Ozer & Weiss, 2004).

Some psychologists have suggested that PTSD has been overdiagnosed, due partly to a broader definition of trauma (Dobbs, 2009; McNally, 2003). Also, too often, say some critics, PTSD gets stretched to include normal bad memories and dreams after a bad experience. In such cases, some well-intentioned procedures used to treat PTSD may make people feel worse (Wakefield & Spitzer, 2002). For example, survivors may be “debriefed” right after a trauma and asked to revisit the experience and vent their emotions. This tactic has been generally ineffective and sometimes harmful (Devilly et al., 2006; McNally et al., 2003; Rose et al., 2003). Nevertheless, people diagnosed with PTSD can benefit from other therapies, some of which are discussed in Chapter 14.

Most people, male and female, display an impressive survivor resiliency, or ability to recover after severe stress (Bonanno, 2004, 2005, 2006). For more on human resilience, and on the posttraumatic growth that some experience, see Chapter 14.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.5

Those who express anxiety through unwanted repetitive thoughts or actions may have a(n) __________ - __________ disorder. Those with symptoms of recurring memories and nightmares, social withdrawal, jumpy anxiety, numbness of feeling, and/or insomnia for weeks after a traumatic event may be diagnosed with _________________ __________ disorder.

obsessive-compulsive; posttraumatic stress

Understanding Anxiety Disorders, OCD, and PTSD

13-8 How do learning and biology contribute to the feelings and thoughts found in anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD?

Anxiety is both a feeling and a thought—a doubt-laden appraisal of one’s safety or social skill. How do these anxious feelings and thoughts arise? Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory (Chapter 11) proposed that, beginning in childhood, people repress certain impulses, ideas, and feelings. This submerged mental energy sometimes, he thought, leaks out in odd symptoms, such as anxious hand washing. Few of today’s psychologists interpret anxiety this way. Most believe that three modern perspectives—conditioning, cognition, and biology—are more helpful.

Conditioning

We are more likely to develop anxiety or PTSD when bad events happen unpredictably and uncontrollably (Field, 2006; Mineka & Zinbarg, 2006). In experiments, researchers have shown how classical conditioning can link our fear responses to formerly neutral objects and events. You may recall from Chapter 6 that the infant called “Little Albert” learned to fear furry objects that were paired with loud noises. And by giving rats unpredictable electric shocks, researchers have created anxious animals (Schwartz, 1984). The rats, like assault victims who report feeling anxious when returning to the scene of the crime, became uneasy in their lab environment. The lab had become a cue for fear.

380

Such research helps explain how panic-prone people come to associate anxiety with certain cues and why anxious or traumatized people are so attentive to possible threats. In one survey, 58 percent of those with social anxiety disorder said their disorder began after a traumatic event (Ost & Hugdahl, 1981).

Two other conditioning processes, stimulus generalization and reinforcement, can magnify a single painful and frightening event into a full-blown phobia. Stimulus generalization occurs when a person experiences a fearful event and later develops a fear of similar events. My car was once struck by another whose driver missed a stop sign. For months afterward, I felt a twinge of unease when any car approached from a side street. My fear eventually disappeared, but for others, fear may linger and grow. Marilyn’s phobia of thunderstorms (a phobia shared by recording artist Madonna) may have similarly generalized after a terrifying or painful experience during a thunderstorm.

Once phobias develop and generalize, they can be maintained by reinforcement, a part of operant conditioning. Anything that helps us avoid or escape from a feared situation reduces our anxiety. This feeling of relief can reinforce phobic behaviors. Fearing a panic attack, a person may decide not to leave the house. Reinforced by feeling calmer, the person is likely to repeat that maladaptive behavior in the future (Antony et al., 1992). Compulsive behaviors operate similarly. If washing your hands relieves your feelings of anxiety, you may wash your hands again when those feelings return.

Cognition

We learn some fears by observing others. For example, why do nearly all monkeys raised in the wild fear snakes, yet lab-raised monkeys do not? Surely, most wild monkeys do not actually suffer snake bites. Do they learn their fear through observation? To find out, one researcher experimented (Mineka, 1985, 2002). Her study focused on six monkeys raised in the wild (all strongly fearful of snakes) and their lab-raised offspring (none of which feared snakes). The young monkeys repeatedly observed their parents or peers refusing to reach for food in the presence of a snake. Can you predict what happened? The young monkeys also developed a strong fear of snakes. When they were retested three months later, their learned fear persisted. We humans learn many of our own fears by observing others (Olsson et al., 2007).

Our interpretations and expectations also shape our reactions. Whether we panic in response to a creaky sound in an old house depends on whether we interpret the sound as the wind or as a possible knife-wielding intruder. These misinterpretations can develop into irrational beliefs. A pounding heart is seen as a sign of a heart attack. A lone spider near the bed becomes a likely infestation. An everyday disagreement with a partner or boss spells possible doom for the relationship. These thoughts can trigger the overly watchful state known as hypervigilance. Feelings of anxiety are common when people cannot switch off such intrusive thoughts and perceive a loss of control and a sense of helplessness (Franklin & Foa, 2011).

Biology

There is, however, more to anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD than learning. Why will some of us develop lasting phobias or PTSD after suffering traumas? Why are some of us more vulnerable to learned fears? Why do we all learn some fears more easily than others? The biological perspective offers insight.

GENES Genes matter. Among monkeys, fearfulness runs in families. A monkey reacts more strongly to stress if its close biological relatives have sensitive, highstrung temperaments (Suomi, 1986).

So, too, with people. Some of us have genes that make us like orchids—fragile, yet capable of beauty under favorable circumstances. Others of us are like dandelions—hardy, and able to thrive in varied circumstances (Ellis & Boyce, 2008). Thus, some of us are genetically predisposed to anxiety, OCD, and PTSD. If one identical twin has an anxiety disorder, the other is likewise at risk (Hettema et al., 2001; Kendler et al., 2002a,b; Taylor, 2011). Even when raised separately, identical twins may develop similar phobias (Carey, 1990; Eckert et al., 1981). One pair of separated identical twins independently became so afraid of water that, even at age 35, they would wade into the ocean backwards and only up to their knees. Researchers have found genes associated with OCD (Dodman et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2006) and with typical anxiety disorder symptoms (Hovatta et al., 2005).

THE BRAIN Traumatic experiences alter our brain, paving new pathways. These fear pathways create easy inroads for more fear experiences (Armony et al., 1998). Generalized anxiety, panic attacks, phobias, and PTSD reflect a brain danger detection system gone hyperactive—producing anxiety when no danger exists.

381

Generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks, PTSD, and OCD express themselves biologically as overarousal of brain areas involved in impulse control and habitual behaviors. When the disordered brain detects that something is wrong, it seems to generate a mental hiccup of repeating thoughts or actions (Gehring et al., 2000). Our brain’s frontal lobes—where we make plans and form judgments—are among the affected areas. Brain scans of people with OCD show elevated activity in specific frontal lobe brain areas during behaviors such as compulsive hand washing, checking, ordering, or hoarding (Insel, 2010; Mataix-Cols et al., 2004, 2005).

NATURAL SELECTION No matter how fearful or fearless we are, we humans seem biologically prepared to fear the threats our ancestors faced—spiders and snakes, enclosed spaces and heights, storms and darkness. (In the distant past, those who did not fear these threats were less likely to survive and leave descendants.) Thus, even in Britain, which has only one poisonous snake species, people often fear snakes. And we have these fears at very young ages. Preschool children detect snakes in a scene faster than they spot flowers, caterpillars, or frogs (LoBue & DeLoache, 2008). Our Stone Age fears are easy to condition and hard to extinguish (Davey, 1995; Öhman, 1986).

Some of our modern fears may also stem from our evolutionary past. For example, a fear of flying may have grown from a fear of confinement and heights, which can be traced to our biological past. Our phobias focus on dangers our ancestors faced.

Compare these easily conditioned fears to what we humans don’t easily learn to fear. World War II air raids, for example, produced remarkably few lasting phobias. As the air strikes continued, the British, Japanese, and German populations did not become more and more panicked. Rather, they grew more indifferent to planes outside their immediate neighborhood (Mineka & Zinbarg, 1996). Evolution has not prepared us to fear bombs dropping from the sky.

Just as our phobias focus on dangers faced by our ancestors, our compulsive acts typically exaggerate behaviors that contributed to our species’ survival. Grooming gone wild becomes hair pulling. Washing up becomes ritual hand washing. Checking territorial boundaries becomes repeatedly rechecking an already locked door (Rapoport, 1989).

The biological perspective explains a great deal, but it cannot explain the sharp increase in the anxiety levels of U.S. children and college students over the last half-century. That increase appears related to unrealistic expectations, a greater focus on the self than on the community, and a loss of social support (Twenge, 2000). Thus, natural selection shapes our anxious tendencies, but culture and experience also influence our reactions.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 13.6

Researchers believe that anxiety disorders, OCD, and PTSD are influenced by conditioning and cognition. What other factors contribute to these disorders?

Biological factors also play a role. They may include inherited temperament and other gene variations; learned fears that have altered brain pathways; and outdated, inherited responses that had survival value for our distant ancestors.