The Biomedical Therapies

Psychotherapy is one way to treat psychological disorders. The other, often used with the most serious disorders, is biomedical therapy, which changes the brain’s chemistry with drugs or affects the brain’s circuitry with electrical stimulation, magnetic impulses, or psychosurgery. Primary care providers prescribe most drugs for anxiety and depression, followed by psychiatrists and, in some states, psychologists.

Psychotherapy is one way to treat psychological disorders. The other, often used with the most serious disorders, is biomedical therapy, which changes the brain’s chemistry with drugs or affects the brain’s circuitry with electrical stimulation, magnetic impulses, or psychosurgery. Primary care providers prescribe most drugs for anxiety and depression, followed by psychiatrists and, in some states, psychologists.

Drug Therapies

14-13 What are the drug therapies? How do double-blind studies help researchers evaluate a drug’s effectiveness?

By far the most widely used biomedical treatments today are the drug therapies. Since the 1950s, drug researchers have written a new chapter in the treatment of people with severe disorders. Thanks to drug therapies and support from community mental health programs, the resident population of U.S. state and county mental hospitals has dropped to a small fraction of what it was a half-century ago. In one decade alone (1996 to 2005), the number of Americans prescribed antidepressant drugs doubled, from 13 million to 27 million (Olfson & Marcus, 2009).

425

Almost any new treatment, including drug therapy, is greeted by an initial wave of enthusiasm as many people apparently improve. But that enthusiasm often diminishes on closer examination. To judge the effectiveness of a new treatment, we also need to know more:

- Do untreated people also improve? If so, how many, and how quickly?

- Was recovery due to the drug or to the placebo effect? When patients and/or mental health workers expect positive results, they may see what they expect, not what really happens.

To control for these influences when testing a new drug, researchers give half the patients the drug, and the other half a similar-appearing placebo. Because neither the staff nor the patients know who gets which, this is called a double-blind technique. The good news: In double-blind studies, several types of drugs have proven useful in treating psychological disorders.

The four most common drug treatments for psychological disorders are antipsychotic drugs, antianxiety drugs, antidepressant drugs, and mood-stabilizing medications. Let’s consider each of these in more detail.

Antipsychotic Drugs

Accidents sometimes launch revolutions. In this instance, an accidental discovery launched a treatment revolution for people with psychoses. The discovery was that some drugs used for other medical purposes calmed the hallucinations or delusions that are part of the split from reality for these patients. Antipsychotic drugs, such as chlorpromazine (sold as Thorazine), reduce patients’ overreactions to irrelevant stimuli. Thus, they provide the most help to schizophrenia patients experiencing symptoms such as auditory hallucinations and paranoia (Lehman et al., 1998; Lenzenweger et al., 1989). (Antipsychotic drugs are not equally effective in changing symptoms such as apathy and withdrawal.)

How do antipsychotic drugs work? They mimic certain neurotransmitters. Some block the activity of dopamine by occupying its receptor sites. This finding reinforces the idea that an overactive dopamine system contributes to schizophrenia. Further support for this idea comes from a side effect of another drug. L-dopa is a drug sometimes given to people with Parkinson’s disease to boost their production of dopamine, which is too low in Parkinson’s. L-dopa raises dopamine levels, but can you guess its occasional side effect? If you guessed hallucinations, you’re right.

Do antipsychotic drugs also have side effects? Yes, and some are powerful. They may produce sluggishness, tremors, and twitches similar to those of Parkinson’s disease (Kaplan & Saddock, 1989). Long-term use of antipsychotics can also produce tardive dyskinesia, with involuntary movements of the facial muscles (such as grimacing), tongue, and limbs. Although not more effective in controlling schizophrenia symptoms, many of the newer-generation antipsychotics (such as risperidone and olanzapine) have fewer of these effects. These drugs may, however, increase the risk of obesity and diabetes (Buchanan et al., 2010; Tiihonen et al., 2009).

Despite their drawbacks, antipsychotics, combined with life-skills programs and family support, have given new hope to many people with schizophrenia (Guo, 2010). Hundreds of thousands of patients have left the wards of mental hospitals and returned to work and to near-normal lives (Leucht et al., 2003). Elyn Saks, a University of Southern California law professor, knows what it means to live with schizophrenia. Thanks to her treatment, which combines an antipsychotic drug and psychotherapy, “Now I’m mostly well. I’m mostly thinking clearly. I do have episodes, but it’s not like I’m struggling all of the time to stay on the right side of the line” (Saks, 2007).

426

Antianxiety Drugs

Like alcohol, antianxiety drugs, such as Xanax or Ativan, depress central nervous system activity (and so should not be used in combination with alcohol). These drugs are often used in combination with psychological therapy to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. They calm anxiety as the person learns to cope with frightening situations and fear-triggering stimuli.

Some critics fear that antianxiety drugs may reduce symptoms without resolving underlying problems, especially when used as an ongoing treatment. “Popping a Xanax” at the first sign of tension can provide immediate relief, which may reinforce a person’s tendency to take drugs when anxious. Regular heavy use can also lead, when the person stops taking the drugs, to physical problems, such as increased anxiety and insomnia.

Antidepressant Drugs

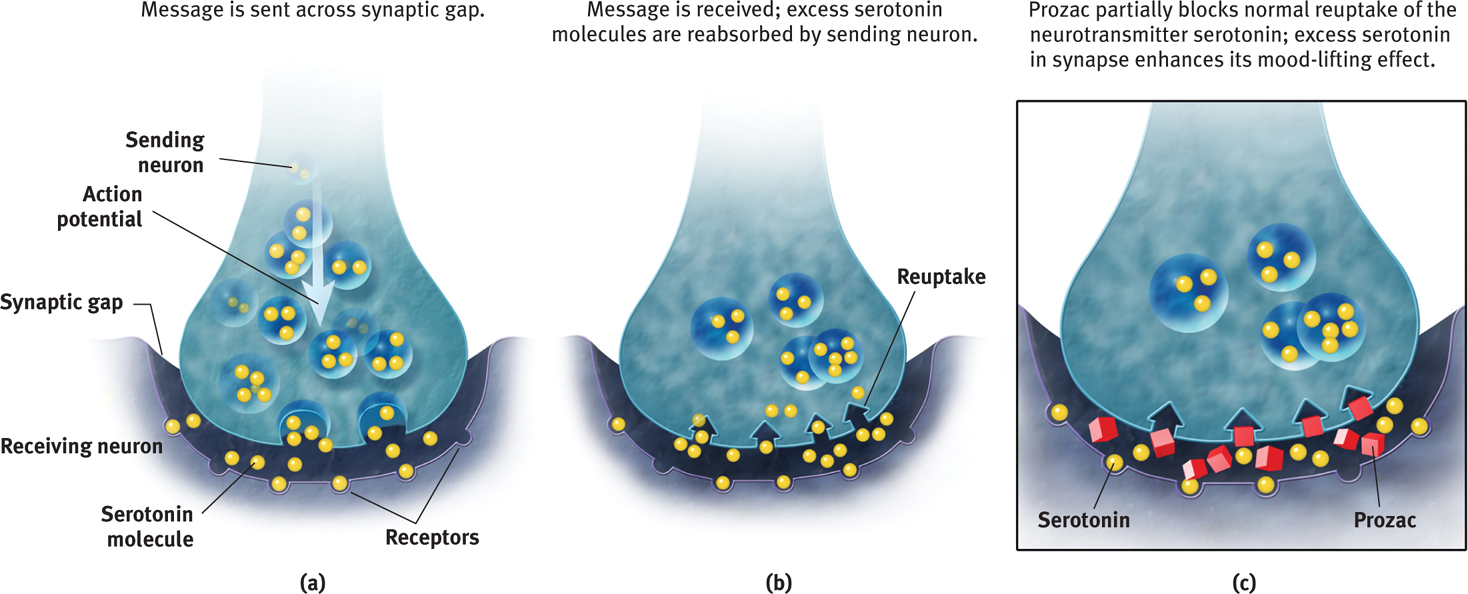

The antidepressant drugs were named for their ability to lift people up from a state of depression. These drugs are now also used to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder. They work by increasing the availability of norepinephrine or serotonin. These neurotransmitters elevate arousal and mood and are scarce when a person experiences feelings of depression or anxiety.

Fluoxetine, which tens of millions of users worldwide have known as Prozac, lifts spirits by prolonging the time serotonin molecules remain in the brain’s synapses. It does this by partially blocking the normal reuptake process (FIGURE 14.5). Prozac and its cousins Zoloft and Paxil are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) because they slow (inhibit) the synaptic vacuuming up (reuptake) of serotonin.

Given their widening use, some professionals prefer the SSRI drugs, rather than antidepressants (Kramer, 2011). SSRIs begin to influence neurotransmission within hours. But their full psychological effect may take four weeks, possibly because these drugs promote the birth of new brain cells (Becker & Wojtowicz, 2007; Jacobs, 2004).

Drugs are not the only way to lift our mood. Aerobic exercise can calm people who feel anxious, energize those who feel depressed, and offer other positive side effects. (More about that later in this chapter.) Cognitive therapy, which helps people reverse their habits of thinking negatively, can boost the drug-aided relief from depression and reduce post-treatment relapses (Hollon et al., 2002; Keller et al., 2000; Vittengl et al., 2007). The best approach seems to be attacking depression (and anxiety) from both above and below (Cuijpers et al., 2010; Walkup et al., 2008). Cognitive-behavioral therapy works from the top down to change thought processes. Antidepressant drugs work from the bottom up to affect the emotionforming limbic system.

People with depression often improve after a month on antidepressant drugs. But after allowing for natural recovery (the return to normal called spontaneous recovery) and the placebo effect, how big is the drug effect? Not big, report some researchers (Kirsch et al., 1998, 2002, 2010). In double-blind clinical trials, placebos produced improvement comparable to about 75 percent of the active drug’s effect. In a follow-up review that included unpublished clinical trials, the antidepressant effect was again modest (Kirsch et al., 2008). The placebo effect was less for those with severe depression, which made the added benefit of the drug somewhat greater for them (Fournier et al., 2010; Kirsch et al., 2008; Olfson & Marcus, 2009). “Given these results, there seems little reason to prescribe antidepressant medication to any but the most severely depressed patients, unless alternative treatments have failed,” concluded one researcher (BBC, 2008).

427

Mood-Stabilizing Medications

In addition to antipsychotic, antianxiety, and antidepressant drugs, psychiatrists have mood-stabilizing drugs in their arsenal. One of them, Depakote, was originally used to treat epilepsy. It was also found effective in controlling the manic episodes associated with bipolar disorder. Another, the simple salt lithium, effectively levels the emotional highs and lows of this disorder. Australian physician John Cade discovered this in the 1940s when he administered lithium to a patient with severe mania and the patient became perfectly well in less than a week (Snyder, 1986). Although we do not understand why, lithium works. About 7 in 10 people with bipolar disorder benefit from a long-term daily dose of this cheap salt (Solomon et al., 1995). Their risk of suicide is but one-sixth that of patients with bipolar disorder not taking lithium (Tondo et al., 1997). Kay Redfield Jamison (1995, pp. 88–89) described the effect:

Lithium prevents my seductive but disastrous highs, diminishes my depressions, clears out the wool and webbing from my disordered thinking, slows me down, gentles me out, keeps me from ruining my career and relationships, keeps me out of a hospital, alive, and makes psychotherapy possible.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.12

How do researchers evaluate the effectiveness of particular drug therapies?

Researchers assign people to treatment and no-treatment conditions to see if those who receive the drug therapy improve more than those who don’t. Double-blind controlled studies are most effective. If neither the therapist nor the patient knows which participants have received the drug treatment, then any difference between the treated and untreated groups will reflect the drug treatment’s actual effect.

Question 14.13

The drugs given most often to treat depression are called ____________. The drugs that are now often given to treat anxiety disorders are called ____________. Schizophrenia is often treated with ____________ drugs.

antidepressants; antidepressants (The antidepressants have been shown to be effective at treating both depression and anxiety.); antipsychotic

Brain Stimulation

14-14 How are brain stimulation and psychosurgery used in treating specific disorders?

Electroconvulsive Therapy

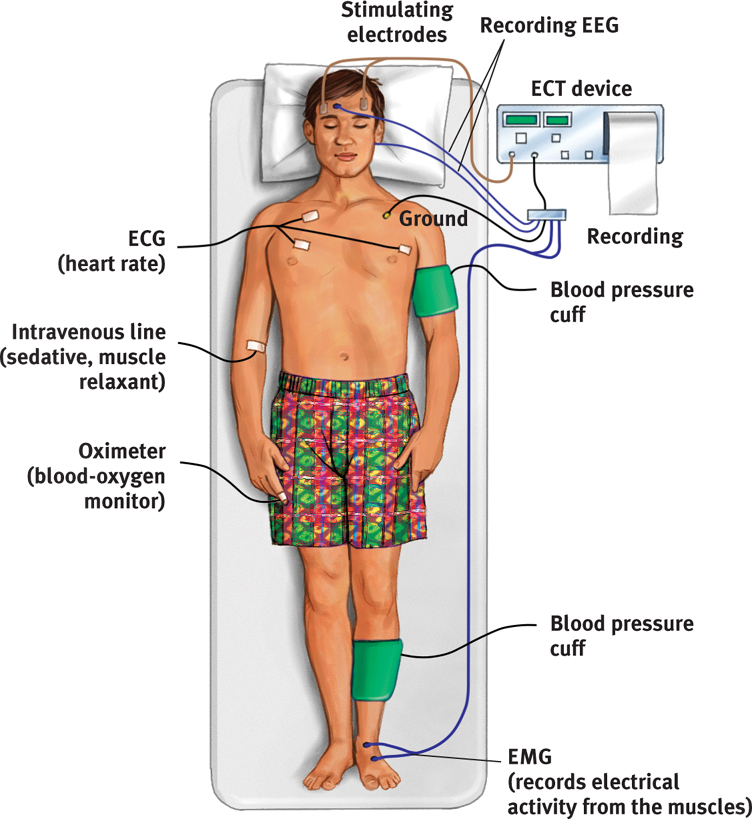

Another biomedical treatment, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), manipulates the brain by shocking it. When ECT was first introduced in 1938, the wide-awake patient was strapped to a table and jolted with roughly 100 volts of electricity to the brain. The procedure, which produced racking convulsions and brief unconsciousness, gained a barbaric image. Although that image lingers, ECT has changed. Today, the patient receives a general anesthetic and a muscle relaxant to prevent convulsions. A psychiatrist then delivers to the patient’s brain 30 to 60 seconds of electric current, in briefer pulses, sometimes only to the brain’s right side (FIGURE 14.6). Within 30 minutes, the patient awakens and remembers nothing of the treatment or of the preceding hours.

Would you agree to ECT for yourself or a loved one? The decision might be difficult, but the treatment works. Shocking as it may seem, study after study confirms that ECT can effectively treat severe depression in patients who have not responded to drug therapy (Bailine et al., 2010; Fink, 2009; UK ECT Review Group, 2003). After three such sessions each week for two to four weeks, 80 percent or more of those receiving ECT improve markedly. They show some memory loss for the treatment period but no apparent brain damage (Bergsholm et al., 1989; Coffey, 1993). Modern ECT causes less memory disruption than earlier versions did (HMHL, 2007).

A Journal of the American Medical Association editorial concluded that “the results of ECT in treating severe depression are among the most positive treatment effects in all of medicine” (Glass, 2001). ECT reduces suicidal thoughts and is credited with saving many from suicide (Kellner et al., 2005).

How does ECT relieve severe depression? After more than 75 years, no one knows for sure. One patient compared ECT to the smallpox vaccine, which was saving lives before we knew how it worked. Perhaps the brief electric current calms neural centers where overactivity produces depression. ECT, like antidepressant drugs and exercise, also appears to boost the production of new brain cells (Bolwig & Madsen, 2007). ECT and antidepressants also share similarity in how they influence serotonin (Yatham et al., 2010).

Skeptics have offered another possible explanation: ECT may trigger a placebo effect. Most ECT studies have failed to include a control group of patients who were randomly assigned to receive the same general anesthesia and to undergo simulated ECT, but without the shock. When given this placebo treatment, patients’ expectation of positive results is therapeutic without the shock (Read & Bentall, 2010). Nevertheless, a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2011) research review concluded that ECT is more effective than a placebo, especially in the short run.

428

No matter how impressive the results, the idea of electrically shocking a person’s brain still strikes many as barbaric, especially given our ignorance about why ECT works. Moreover, the mood boost may not last long. About 4 in 10 ECT-treated patients have relapsed into depression within six months, with or without follow-up drug therapy (Kellner et al., 2006; Tew et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, in the minds of many psychiatrists and patients, ECT is a lesser evil than severe depression’s misery, anguish, and risk of suicide. As one psychologist reported after ECT relieved his deep depression, “A miracle had happened in two weeks” (Endler, 1982).

Alternative Neurostimulation Therapies

To jump-start the depressed brain, scientists have developed some gentler alternatives (Moreines et al., 2011). Vagus nerve stimulation stimulates a nerve in the neck, via an electrical device implanted in the chest. The device periodically sends signals to the brain’s mood-related limbic system, increasing available serotonin by boosting the firing rates of some neurons (Fitzgerald & Daskalakis, 2008; Marangell et al., 2007).

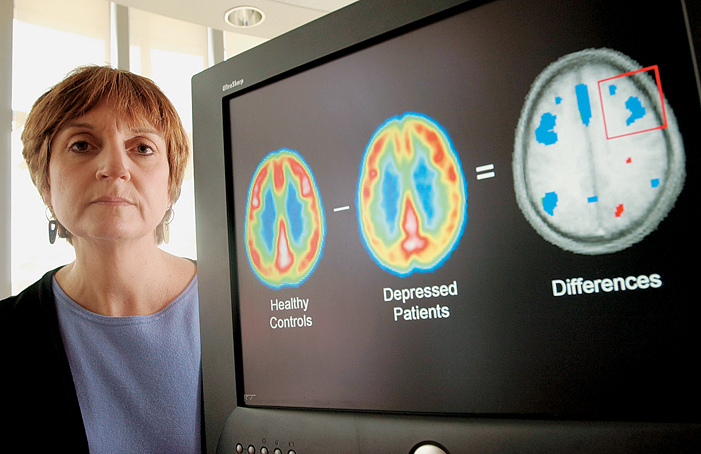

Another experimental procedure, deep-brain stimulation, manipulates the depressed brain by means of a pacemaker that activates implanted electrodes in brain areas that feed negative emotions and thoughts (Lozano et al., 2008; Mayberg et al., 2005). The stimulation inhibits activity in those brain areas. With deep-brain stimulation, some patients whose depression did not respond to drugs or ECT have found their depression lifting. Others have become more responsive to drugs or psychotherapy.

Deep-brain stimulation may show promise in other treatment areas. By inhibiting activity in areas associated with pleasure and reward, it may curb an addict’s urges to use drugs and alcohol (Luigjes et al., 2012). But investigators caution that the science is new and more research is needed (Hamani et al., 2009; Rabins et al., 2009).

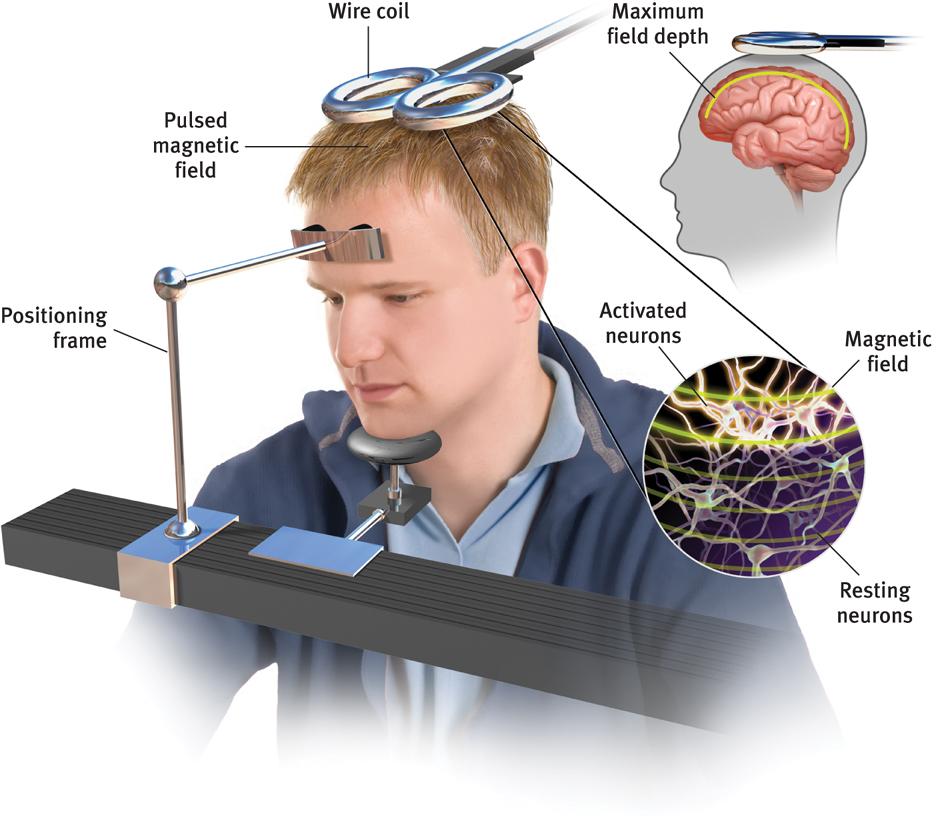

Depressed moods also seem to improve when repeated pulses of magnetic energy are applied to a person’s brain. In a painless procedure called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), a coiled wire held close to the skull sends a magnetic field to the brain (FIGURE 14.7). Unlike deep-brain stimulation, the magnetic energy penetrates only to the brain’s surface. And unlike ECT, the rTMS procedure produces no memory loss or other serious side effects. (Headaches can result.) Wide-awake patients receive this treatment daily for two to four weeks.

429

Initial studies have found “modest” positive benefits of rTMS (Daskalakis et al., 2008; George et al., 2010; López-Ibor et al., 2008). In one study, a woman with bipolar disorder benefited more from rTMS than from ECT (Zeeuws et al., 2011). How it works is not yet clear. One possible explanation is that the stimulation energizes the brain’s left frontal lobe, which is relatively inactive during depression (Helmuth, 2001). Repeated stimulation may cause nerve cells to form new functioning circuits through the process of long-term potentiation. (For more on long-term potentiation, see Chapter 7.)

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.14

Severe depression that has not responded to other therapy may be treated with _________ __________, which can cause memory loss. More moderate neural stimulation techniques designed to help alleviate depression include _________ _________ stimulation, ____________-____________ stimulation, and ____________ magnetic stimulation.

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); vagus nerve; deep-brain; repetitive transcranial

Psychosurgery

Psychosurgery is surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue in an attempt to change thoughts and behaviors. Because its effects are irreversible, it is the least-used biomedical therapy.

In the 1930s, Portuguese physician Egas Moniz developed what would become the best-known psychosurgical operation: the lobotomy. He (and, later, other neurosurgeons) used it to calm uncontrollably emotional and violent patients. His crude but easy and inexpensive procedure took only about 10 minutes:

- Step 1. Shock the patient into a coma.

- Step 2. Hammer an instrument shaped like an icepick through each eye socket. Drive it into the brain.

- Step 3. Wiggle the instrument to cut nerves connecting the frontal lobes with the emotion-controlling centers of the inner brain.

430

Tens of thousands of severely disturbed people received lobotomies between 1936 and 1954. By that time, some 35,000 people had been lobotomized in the United States alone.

For his work, Moniz received a Nobel Prize (Valenstein, 1986). But today, lobotomies are history. Their intention was simply to disconnect emotion from thought, and indeed, they did usually decrease misery or tension. But their effect was often more drastic, leaving people permanently listless, immature, and uncreative. During the 1950s, when calming drugs became available, psychosurgery was largely abandoned. Today, more precise micropsychosurgery is sometimes used in extreme cases. For example, if a patient has uncontrollable seizures, surgeons can destroy the specific nerve clusters that cause or transmit the convulsions. MRI-guided precision surgery is also occasionally done to cut the circuits involved in severe obsessive-compulsive disorder (Carey, 2009, 2011; Sachdev & Sachdev, 1997). Because these procedures cannot be reversed, neurosurgeons perform them only as a last resort.

Therapeutic Lifestyle Change

14-15 How, by adopting a healthier lifestyle, might people find some relief from depression?

The effectiveness of the biomedical therapies reminds us of a fundamental lesson. We find it convenient to talk of separate psychological and biological influences, but everything psychological is also biological. Every thought and feeling depends on the functioning brain. Every creative idea, every moment of joy or anger, every period of depression emerges from the electrochemical activity of the living brain. The influence is two-way. When psychotherapy relieves behaviors associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder or schizophrenia, PET scans reveal a calmer brain (Habel et al., 2010; Schwartz et al., 1996).

For years, we have considered the health of our body and mind separately. That neat separation no longer seems valid. Stress affects body chemistry and health. And chemical imbalances, whatever their cause, can produce psychological disorders.

That lesson is now being applied in training seminars promoting therapeutic lifestyle change (Ilardi, 2009). Two basic ideas behind these sessions are that human brains and bodies were designed for physical activity and social engagement, and that our ancestors hunted, gathered, and built in groups, with little evidence of disabling depression.

Those whose way of life includes regular physical activity, strong community ties, sunlight exposure, and plenty of sleep rarely experience major depression. Depression is nearly absent in America’s Amish farming communities. Whether we are children or adults, outdoor activity in a natural environment—perhaps a walk in the woods—can reduce stress and promote health (NEEF, 2011; Phillips, 2011).

Research shows that regular aerobic exercise rivals the healing power of antidepressant drugs (Babyak et al., 2000; Salmon, 2001). And a complete night’s sleep boosts mood and energy (Gregory et al., 2009; Walker & van der Helm, 2009). In the lifestyle change sessions, small groups of people with depression undergo a 12-week training program with the following goals:

- Aerobic exercise, 30 minutes a day, at least three times weekly (increases fitness and vitality, stimulates endorphins)

- Adequate sleep, with a goal of 7 to 8 hours a night (increases energy and alertness, boosts immunity)

- Light exposure, at least 30 minutes each morning with a light box (amplifies arousal, influences hormones)

- Social connection, with less alone time and at least two meaningful social engagements weekly (helps satisfy the human need to belong)

- Antirumination, by identifying and redirecting negative thoughts (enhances positive thinking)

- Nutritional supplements, including a daily fish oil supplement with omega-3 fatty acids (aids in healthy brain functioning)

In one study of 74 people, 77 percent of those who completed the program experienced relief from depressive symptoms. In contrast, only 19 percent of those assigned to a treatment-as-usual control group showed similar results. Though in need of replication, these results are striking. Future research will try to identify which parts of the treatment produce the therapeutic effect. But there seems little reason to doubt the truth of the Latin saying, Mens sana in corpore sano: “A healthy mind in a healthy body” (FIGURE 14.8).

* * *

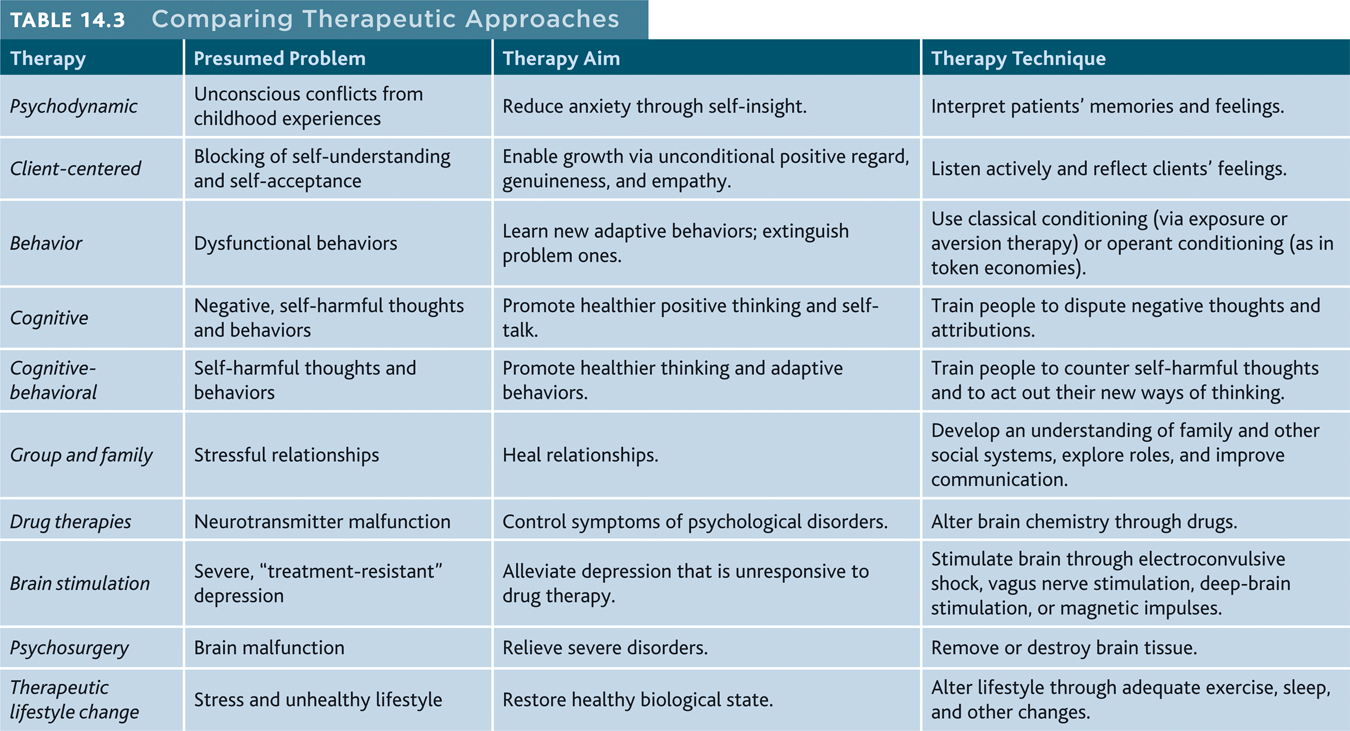

TABLE 14.3 summarizes the therapies discussed in this chapter.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 14.15

What are some examples of lifestyle changes we can make to enhance our mental health?

Exercise regularly, get enough sleep, get more exposure to light, nurture important relationships, redirect negative thinking, and eat a diet rich in omega-3 fatty acids.