Four Big Ideas in Psychology

1-3 What four big ideas run throughout this book?

I have used four of psychology's big ideas to organize material in this book.

I have used four of psychology's big ideas to organize material in this book.

- Critical thinking Science supports thinking that examines assumptions, uncovers hidden values, weighs evidence, and tests conclusions. Science-aided thinking is smart thinking.

- The biopsychosocial approach We can view human behavior from three levels—the biological, psychological, and social-cultural. We share a biologically rooted human nature. Yet cultural and psychological influences fine-tune our assumptions, values, and behaviors.

- The two-track mind Today's psychological science explores our dual-processing capacity. Our perception, thinking, memory, and attitudes all operate on two levels: a conscious, aware track, and an unconscious, automatic, unaware track. It has been a surprise to learn how much information processing happens without our awareness.

- Exploring human strengths Psychology today focuses not only on understanding and offering relief from troublesome behaviors and emotions, but also on understanding and building the emotions and traits that help us to thrive.

6

Let's consider these four big ideas, one by one.

Big Idea 1: Critical Thinking Is Smart Thinking

Whether reading a news report or swapping ideas with others, critical thinkers ask questions. How do we know that? Who benefits from this? Is the conclusion based on guesswork and gut feelings, or on evidence? How do we know one event caused the other? How else could we explain things?

In psychology, critical thinking has led to some surprising findings. Believe it or not…

- massive losses of brain tissue early in life may have few long-term effects (see Chapter 2).

- within days, newborns can recognize their mother's odor (Chapter 3).

- some people with brain damage can learn new skills, yet at the mind's conscious level be unaware that they have these skills (Chapter 7).

- most of us—male and female, young and old, wealthy and not wealthy, with and without disabilities—report roughly the same levels of personal happiness (Chapter 10).

- an electric shock delivered to the brain (electroconvulsive therapy) may relieve severe depression when all else has failed (Chapter 14).

This same critical thinking has also debunked some popular beliefs. When we let the evidence speak for itself, we learn that…

- sleepwalkers are not acting out their dreams (Chapter 2).

- our past is not precisely recorded in our brain. Neither brain stimulation nor hypnosis will let us push “play” and relive long-buried memories (Chapter 7).

- most of us do not suffer from low self-esteem, and high self-esteem is not all good (Chapter 11).

- opposites do not generally attract (Chapter 12).

In later chapters, you'll see many more examples of research in which critical thinking has challenged our beliefs and triggered new ways of thinking.

Big Idea 2: Behavior Is a Biopsychosocial Event

Each of us is part of a larger social system—a family, a group, a society. But each of us is also made up of smaller systems, such as our nervous system and body organs, which are composed of still smaller systems—cells, molecules, and atoms.

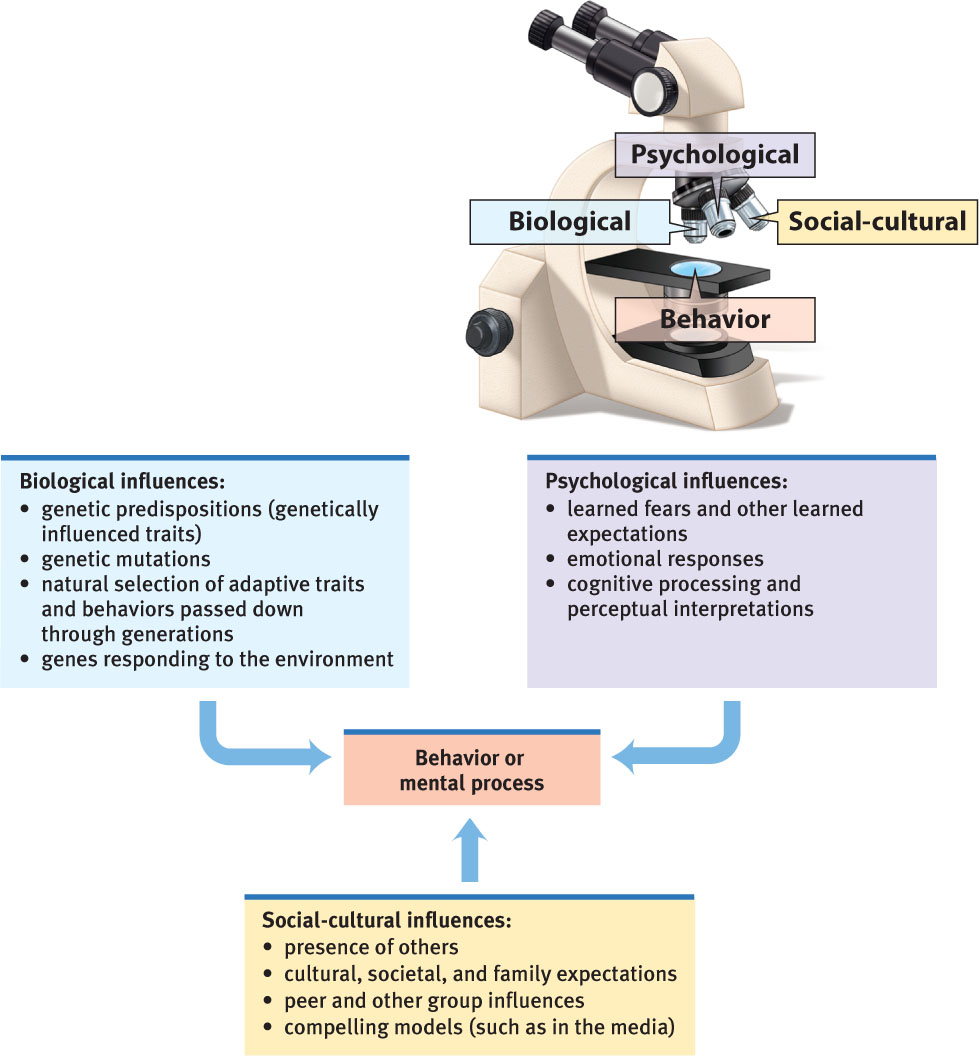

If we study this complexity with simple tools, we may end up with partial answers. Consider: Why do grizzly bears hibernate? Is it because hibernation helped their ancestors to survive and reproduce? Because their biology drives them to do so? Because cold climates hinder food gathering during winter? Each of these is a partial truth, but none is a full answer. For the best possible view, we need to use many levels of analysis. The biopsychosocial approach integrates three levels: biological, psychological, and social-cultural (Figure 1.1). Each level's viewpoint gives us a valuable insight into a behavior or mental process, and together they offer us the most complete picture.

Antonia Brune

Suppose we wanted to study gender differences in a group of men and women. Gender is not the same as sex. Gender refers to the traits and behaviors we expect in a man or a woman. Sex refers to the biological characteristics people inherit, thanks to their genes. To study gender differences, we would want to know as much as possible about biological influences. But we would also want to understand how the group's culture—the shared ideas and behaviors that one generation passes on to the next—defines male and female. Even with this much information, our view would be incomplete. We would also need some understanding of how the individuals in the group differ from one another because of their personal abilities and learning.

Westend61/SuperStock

7

Studying all these influences, researchers have found some gender differences—in what we dream, in how we express and detect emotion, and in our risk for substance abuse, depression, and eating disorders. Psychologically as well as biologically, women and men differ. But the research shows we are also alike. Whether female or male, we learn to walk at about the same age. We experience the same sensations of light and sound. We feel the same pangs of hunger, desire, and fear. We exhibit similar overall intelligence and well-being.

Psychologists have used the biopsychosocial approach to study many of the field's big questions. One of the biggest and most persistent is the nature-nurture issue: How do we judge the contributions of nature (biology) and nurture (experience)? Today's psychologists explore this age-old question by asking, for example:

- How are differences in intelligence, personality, and psychological disorders influenced by heredity and by environment?

- Is our sexual orientation written in our genes or learned through our experiences?

- Can life experiences affect the activity of our heredity (our genes)?

- Should we treat depression as a disorder of the brain or a disorder of thought—or both?

8

In most cases, nurture works on what nature provides. Our species has been graced with a great biological gift: an enormous ability to learn and adapt. Moreover (and you will read this over and over in the pages that follow), every psychological event—every thought, every emotion—is also a biological event.

Big Idea 3: We Operate With a Two-Track Mind (Dual Processing)

Mountains of new research reveal that our brain works on two tracks. Our conscious mind feels like our body's chief executive, and in fact we do process much information on our brain's conscious track, with full awareness. But at the same time, a surprisingly large unconscious, automatic track is processing information outside of our awareness. Thinking, memory, perception, language, and attitudes all operate on these two tracks. Today's researchers call it dual processing. We know more than we know we know. As a fascinating scientific story illustrates, the truth sometimes turns out to be stranger than fiction.

During my time spent at Scotland's University of St. Andrews, I came to know research psychologists Melvyn Goodale and David Milner (2004, 2006). A local woman, whom they call D. F., was overcome by carbon monoxide one day while showering. The resulting brain damage left her unable to consciously perceive objects. Yet she acted as if she could see them. Asked to slip a postcard into a mail slot, she could do so without error. And although she could not report the width of a block in front of her, she could grasp it with just the right finger-thumb distance.

How could this be? How could a woman who is perceptually blind grasp objects accurately? Goodale and Milner knew from animal research that the eye sends information to different brain areas, each of which has a different task. Sure enough, a scan of D. F.'s brain activity revealed normal activity in the area concerned with reaching for and grasping objects, but not in the area concerned with consciously recognizing objects. So, would the reverse damage lead to the opposite symptoms? Indeed, there are a few such patients. They can see and recognize objects, but they have difficulty pointing toward or grasping them.

We think of our vision as one system: We look, we see, we respond to what we see. Actually, vision is a great example of our dual processing. A visual perception track enables us to think about the world—to recognize things and to plan future actions. A visual action track guides our moment-to-moment actions.

This big idea—that much of our everyday thinking, feeling, sensing, and acting operates outside our awareness—may be a weird new idea for you. It was for me. I long believed that my own intentions and deliberate choices ruled my life. In many ways they do. But in the mind's downstairs, as you will see in later chapters, there is much, much more to being human.

Big Idea 4: Psychology Explores Human Strengths as Well as Challenges

Psychology's first hundred years focused on understanding and treating troubles, such as abuse and anxiety, depression and disease, prejudice and poverty. Much of today's psychology continues the exploration of such challenges. Without slighting the need to repair damage and cure disease, Martin Seligman and others (2002, 2005, 2011) have called for more research on human flourishing. These psychologists call their approach positive psychology. They believe that happiness is a by-product of a pleasant, engaged, and meaningful life. Thus, positive psychology focuses on building a “good life” that engages our skills, and a “meaningful life” that points beyond ourselves. Positive psychology uses scientific methods to explore

- positive emotions, such as satisfaction with the past, happiness with the present, and optimism about the future.

- positive character traits, such as creativity, courage, compassion, integrity, self-control, leadership, wisdom, and spirituality. Current research examines the roots and fruits of such qualities, sometimes by studying the lives of individuals who offer striking examples.

- positive institutions, such as healthy families, supportive neighborhoods, effective schools, and socially responsible media.

Will psychology have a more positive mission in this century? Can it help us all to flourish? An increasing number of scientists worldwide believe it can.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.5

What advantage do we gain by using the biopsychosocial approach in studying psychological events?

By considering different levels of analysis, the biopsychosocial approach can provide a more complete view than any one perspective could offer.

Question 1.6

What is contemporary psychology's position on the nature—nurture debate?

Psychological events often stem from the interaction of nature and nurture, rather than from either of them acting alone.

9