Frequently Asked Questions About Psychology

We have reflected on how a scientific approach can restrain, or limit, biases. We have seen how case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys help us describe behavior. We have also noted that correlational studies assess the association between two factors, showing how well one predicts the other. We have examined the logic underlying experiments, which use controls and random assignment to isolate the effects of independent variables on dependent variables.

We have reflected on how a scientific approach can restrain, or limit, biases. We have seen how case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys help us describe behavior. We have also noted that correlational studies assess the association between two factors, showing how well one predicts the other. We have examined the logic underlying experiments, which use controls and random assignment to isolate the effects of independent variables on dependent variables.

Hopefully, you are now prepared to understand what lies ahead and to think critically about psychological matters. Before we plunge in, let's address some frequently asked questions about psychology.

1-10 How do simplified laboratory conditions help us understand general principles of behavior?

Do you ever wonder whether people's behavior in a research laboratory will predict their behavior in real life? For example, does detecting the blink of a faint red light in a dark room have anything useful to say about flying a plane at night? Or, after viewing a violent, sexually explicit film, does an aroused man's increased willingness to deliver what he thinks are electrical shocks to a woman help us learn whether violent pornography makes a man more likely to abuse a woman?

21

Before you answer, consider this. The experimenter intends to simplify reality—to create a mini-environment that imitates and controls important features of everyday life. Just as a wind tunnel lets airplane designers re-create airflow forces under controlled conditions, a laboratory experiment lets psychologists re-create psychological forces under controlled conditions.

An experiment's purpose is not to re-create the exact behaviors of everyday life but to test theoretical principles (Mook, 1983). In aggression studies, deciding whether to push a button that delivers a shock may not be the same as slapping someone in the face, but the principle is the same. It is the resulting principles—not the specific findings—that help explain everyday behaviors. Many investigations have shown that principles derived in the laboratory do typically generalize to the everyday world (Anderson et al., 1999).

The point to remember: Psychologists are less interested in particular behaviors than in the general principles that help explain many behaviors.

1-11 Why do psychologists study animals, and what ethical guidelines safeguard human and animal research participants?

Many psychologists study animals because they find them fascinating. They want to understand how different species learn, think, and behave. Psychologists also study animals to learn about people. We humans are not like animals; we are animals, sharing a common biology. Animal experiments have therefore led to treatments for human diseases—insulin for diabetes, vaccines to prevent polio and rabies, transplants to replace defective organs.

Humans are more complex. But the same processes by which we learn are present in rats, monkeys, and even sea slugs. The simplicity of the sea slug's nervous system is precisely what makes it so revealing of the neural mechanisms of learning.

“Rats are very similar to humans except that they are not stupid enough to purchase lottery tickets.”

Dave Barry, July 2, 2002

Sharing such similarities, should we respect rather than experiment on our animal relatives? The animal protection movement protests the use of animals in psychological, biological, and medical research.

Out of this heated debate, two issues emerge. The basic one is whether it is right to place the well-being of humans above that of other animals. In experiments on stress and cancer, is it right that mice get tumors in the hope that people might not? Should some monkeys be exposed to an HIV-like virus in the search for an AIDS vaccine? Is our use and consumption of other animals as natural as the behavior of carnivorous hawks, cats, and whales? The answers to such questions vary by culture. In Gallup surveys in Canada and the United States, about 6o percent of adults have said that medical testing on animals is “morally acceptable.” In Britain, only 37 percent have (Mason, 2003).

If we give human life first priority, what safeguards should protect the well-being of animals in research? One survey asked animal researchers if they supported government regulations protecting research animals. Ninety-eight percent supported such protection for primates, dogs, and cats. And 74 percent backed regulations providing for the humane care of rats and mice (Plous & Herzog, 2000). Many professional associations and funding agencies already have such guidelines. British Psychological Society guidelines call for housing animals under reasonably natural living conditions, with companions for social animals (Lea, 2000). American Psychological Association (APA) guidelines state that researchers must ensure the “comfort, health, and humane treatment” of animals and minimize “infection, illness, and pain” (APA, 2002). The European Parliament has set standards for animal care and housing (Vogel, 2010).

22

Animals have themselves benefited from animal research. One Ohio team of research psychologists measured stress hormone levels in samples of millions of dogs brought each year to animal shelters. They devised handling and stroking methods to reduce stress and ease the dogs' move to adoptive homes (Tuber et al., 1999). Other studies have helped improve care and management in animals' natural habitats. Experiments have revealed our behavioral kinship with animals and the remarkable intelligence of chimpanzees, gorillas, and other animals. Experiments have also led to increased empathy and protection for other species. At its best, a psychology concerned for humans and sensitive to animals serves the welfare of both.

What about human participants? Does the image of white-coated scientists delivering electric shocks trouble you? If so, you'll be relieved to know that most psychological studies are free of such stress. With people, blinking lights, flashing words, and pleasant social interactions are more common. Moreover, psychology's experiments are mild compared with the stress and humiliation often inflicted by reality TV shows. In one episode of The Bachelor, a man dumped his new fiancée—on camera, at the producers' request—for the woman who earlier had finished second (Collins, 2009).

Occasionally, though, researchers do temporarily stress or deceive people. This happens only when they believe it is unavoidable. Some experiments, such as those about understanding and controlling violent behavior or studying mood swings, won't work if participants know everything beforehand. (Wanting to be helpful, they might try to confirm the researcher's predictions.)

The APA ethics code urges researchers to

- obtain the participants' informed consent.

- protect them from harm and discomfort.

- keep information about individual participants confidential.

- fully debrief participants (explain the research afterward).

Moreover, most universities now have ethics committees that screen research proposals and safeguard participants' well-being.

1-12 How do personal values influence psychologists' research and application? Does psychology aim to manipulate people?

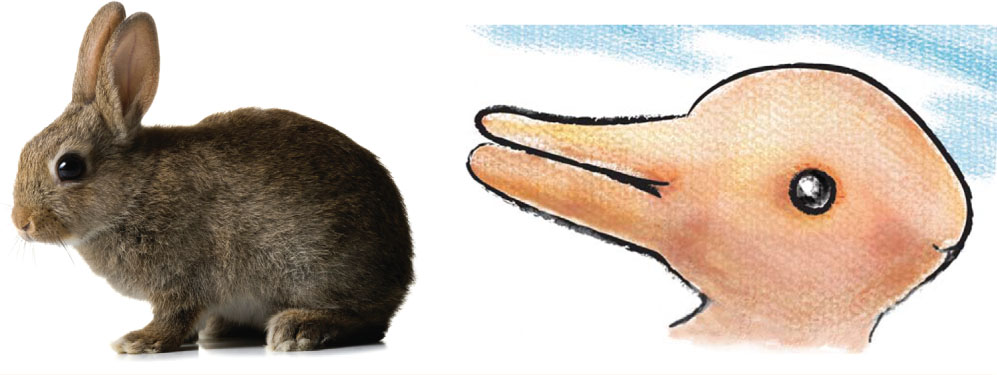

Psychology is definitely not value free. Values affect what we study, how we study it, and how we interpret results. Consider: Researchers' values influence their choice of topics. Should we study worker productivity or worker morale? Sex discrimination or gender differences? Conformity or independence? Our values can also color “the facts.” As noted earlier, what we want or expect to see can bias our observations and interpretations Figure 1.6.

Even the words we use to describe something can reflect our values. Are the sex acts we do not practice perversions or sexual variations? Labels describe and labels evaluate. One person's rigidity is another's consistency. One person's faith is another's fanaticism. One country's enhanced interrogation techniques, such as cold-water immersion, become torture when practiced by its enemies. Our words—firm or stubborn, careful or picky, discreet or secretive—reveal our attitudes.

Applied psychology also contains hidden values. If you defer to “professional” guidance—on raising children, achieving self-fulfillment, coping with sexual feelings, getting ahead at work—you are accepting value-laden advice. A science of behavior and mental processes can certainly help us reach our goals, but it cannot decide what those goals should be.

Some have a different concern: They worry that psychology is becoming dangerously powerful. Is it an accident that astronomy is the oldest science and psychology the youngest? To these questioners, exploring the external universe seems far safer than exploring our own inner universe.

Might psychology, they ask, be used to manipulate people? Knowledge, like all power, can be used for good or evil. Nuclear power has been used to light up cities—and to demolish them. Persuasive power has been used to educate people—and to deceive them. Although psychology does indeed have the power to deceive, its purpose is to enlighten. Every day, psychologists are exploring ways to enhance learning, creativity, and compassion. Psychology speaks to many of our world's great problems—war, climate change, prejudice, family crises, crime—all of which involve attitudes and behaviors. Psychology also speaks to our deepest longings—for nourishment, for love, for happiness. And, as you have seen, one of the new developments in this field—positive psychology—has as its goal exploring and promoting human strengths. Many of life's questions are beyond psychology, but even a first psychology course can shine a bright light on some very important ones.

23

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 1.20

How are human research participants protected?

Researchers using human participants should obtain informed consent, protect them from harm and discomfort, treat personal information confidentially, and fully debrief them after their participation. Ethical principles have been developed by international psychological organizations, and most universities also have ethics committees that safeguard participants' well-being.