Reflections on Gender, Sexuality, and Nature–Nurture Interaction

Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

Our ancestral history helped form us as a species. Where there is variation, natural selection, and heredity, there will be evolution. Our genes form us. This is a great truth about human nature.

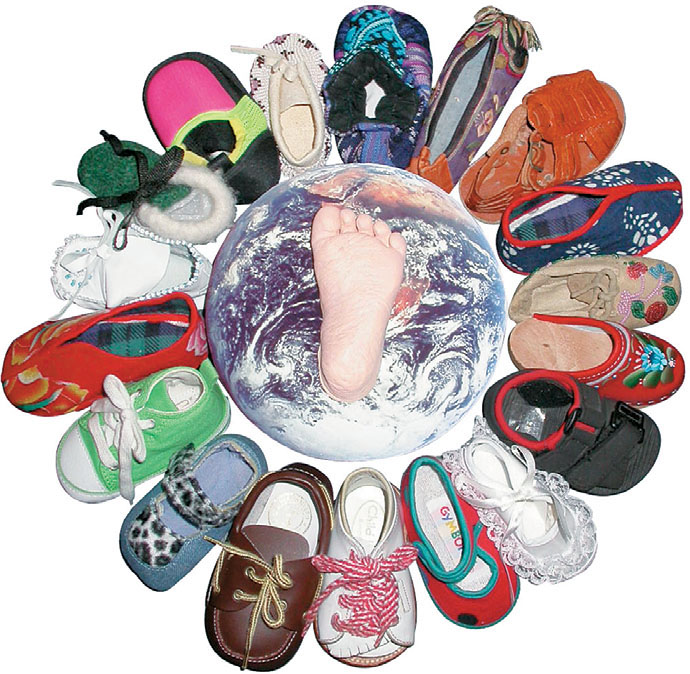

But our culture and experiences also shape us. If their genes and hormones predispose males to be more physically aggressive than females, culture can amplify this gender difference by supporting norms that shower benefits on macho men and on gentle women. If men are encouraged toward roles that demand physical power, and women toward more nurturing roles, each may act accordingly. By exhibiting the actions expected of those who fill such roles, men and women shape their own traits. Presidents in time become more presidential, servants more servile. Gender roles similarly shape us.

In many modern cultures, gender roles are merging. Brute strength is becoming increasingly less important for power and status (think Mark Zuckerberg and Hillary Clinton). From 1960 into the next century, women soared from 6 percent to 50 percent of U.S. medical school students (AMA, 2010). In the mid-1960s, U.S. married women devoted seven times as many hours to housework as did their husbands; by 2003 this gap had shrunk to twice as many (Bianchi et al., 2000, 2006). Such swift changes signal that biology does not fix gender roles.

If nature and nurture jointly form us, are we “nothing but” the product of nature and nurture? Are we rigidly determined?

We are the product of nature and nurture, but we’re also an open system. Genes are all-pervasive but not all-powerful. People may reject their evolutionary role as transmitters of genes and choose not to reproduce. Culture, too, is all-pervasive. Culture bends the genders. But culture is not all-powerful. People may rebel against peer pressures and do the opposite of the expected.

We can’t excuse our failings by blaming them solely on bad genes or bad influences. In reality, we are both the creatures and the creators of our worlds. So many things about us—including our gender identity and mating behaviors—are the products of our genes and environments. Yet the future-shaping stream of causation runs through our present choices. Our decisions today design our environments tomorrow. Mind matters. The human environment is not like the weather—something that just happens randomly. We are its architects. Our hopes, goals, and expectations influence our future. And that is what enables cultures to vary and to change.

129

For Those Troubled by the Scientific Understanding of Human Origins

C L O S E - U P

I [DM] know from my mail that some readers feel troubled by the naturalism and evolutionism of contemporary science. They worry that a science of behavior (and evolutionary science in particular) will destroy our sense of the beauty, mystery, and spiritual significance of the human creature. For those concerned, I offer some reassuring thoughts.

When Isaac Newton explained the rainbow in terms of light of differing wavelengths, British poet John Keats feared that Newton had destroyed the rainbow’s mysterious beauty. Yet, nothing about the science of optics need diminish our appreciation for the drama of a rainbow arching across a rain-darkened sky.

When Galileo assembled evidence that the Earth revolved around the Sun, not vice versa, he did not offer absolute proof for his theory. Rather he offered an explanation that pulled together a variety of observations, such as the changing shadows cast by the Moon’s mountains. His explanation eventually won the day because it described and explained things in a way that made sense, that hung together. Darwin’s theory of evolution likewise offers an organizing principle that makes sense of many observations.

Some people of faith may find the scientific idea of human origins troubling. Many others find that it fits with their own spirituality. Pope John Paul II in 1996 welcomed a science-religion dialogue, finding it noteworthy that evolutionary theory “has been progressively accepted by researchers, following a series of discoveries in various fields of knowledge.”

Meanwhile, many people of science are awestruck at the emerging understanding of the universe and the human creature. It boggles the mind—the entire universe popping out of a point some 14 billion years ago, and instantly inflating to cosmological size. Had the energy of this Big Bang been the tiniest bit less, the universe would have collapsed back on itself. Had it been the tiniest bit more, the result would have been a soup too thin to support life. Had gravity been a teeny bit stronger or weaker, or had the weight of a carbon proton been a wee bit different, our universe just wouldn’t have worked.

What caused this almost-too-good-to-be-true, finely tuned universe? Why is there something rather than nothing? How did it come to be, in the words of Harvard-Smithsonian astrophysicist Owen Gingerich (1999), “so extraordinarily right, that it seemed the universe had been expressly designed to produce intelligent, sentient beings”? Is there a benevolent superintelligence behind it all? On such matters, a humble, awed, scientific silence is appropriate, suggested philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Rather than fearing science, we can welcome its enlarging our understanding and awakening our sense of awe. In a short 4 billion years, life on Earth has come from nothing to structures as complex as a 6-billion-unit strand of DNA and the incomprehensible intricacy of the human brain. Nature seems cunningly and ingeniously devised to produce extraordinary, self-replicating, information-processing systems—us (Davies, 1992, 1999, 2004). Although we appear to have been created from dust, over eons of time, the end result is a priceless creature, one rich with potential beyond our imagining.