Sensory Interaction

5-21 How do our senses interact?

Our senses are not totally separate information channels. In interpreting the world, our brain blends their inputs. Consider what happens to your sense of taste if you hold your nose, close your eyes, and have someone feed you various foods. A slice of apple may be indistinguishable from a chunk of raw potato. A piece of steak may taste like cardboard. Without their smells, a cup of cold coffee may be hard to distinguish from a glass of red wine. To savor a taste, we normally breathe the aroma through our nose—which is why eating is not much fun when you have a bad cold. Smell can also change our perception of taste: A drink’s strawberry odor enhances our perception of its sweetness. Even touch can influence taste. Depending on its texture, a potato chip “tastes” fresh or stale (Smith, 2011). This is sensory interaction at work—the principle that one sense may influence another. Smell + texture + taste = flavor.

Our senses are not totally separate information channels. In interpreting the world, our brain blends their inputs. Consider what happens to your sense of taste if you hold your nose, close your eyes, and have someone feed you various foods. A slice of apple may be indistinguishable from a chunk of raw potato. A piece of steak may taste like cardboard. Without their smells, a cup of cold coffee may be hard to distinguish from a glass of red wine. To savor a taste, we normally breathe the aroma through our nose—which is why eating is not much fun when you have a bad cold. Smell can also change our perception of taste: A drink’s strawberry odor enhances our perception of its sweetness. Even touch can influence taste. Depending on its texture, a potato chip “tastes” fresh or stale (Smith, 2011). This is sensory interaction at work—the principle that one sense may influence another. Smell + texture + taste = flavor.

Vision and hearing may similarly interact. We can see a tiny flicker of light more easily if it is accompanied by a short burst of sound (Kayser, 2007). And we can more easily hear soft sounds if they are paired with visual cues (FIGURE 5.30). If I (as a person with hearing loss) watch a video with on-screen captions, I have no trouble hearing the words I see. But if I then decide I don’t need the captions, and turn them off, I will quickly realize I do need them. The eyes guide the ears.

What do you suppose happens if the eyes and ears disagree? What if we see a speaker saying one syllable while we hear another? Surprise: We may perceive a third syllable that blends both inputs. Seeing the mouth movements for ga while hearing ba, we may perceive da. This is known as the McGurk effect, after one of its discoverers (McGurk & MacDonald, 1976).

We have seen that our perceptions have two main ingredients: Our bottom-up sensations and our top-down cognitions (such as expectations, attitudes, thoughts, and memories). The brain circuits processing our bodily sensations may sometimes interact with brain circuits responsible for cognition.

161

The result is embodied cognition. Some examples:

- Physical warmth may promote social warmth. After holding a warm drink rather than a cold one, people are more likely to rate someone more warmly, feel closer to them, and behave more generously (IJzerman & Semin, 2009; Williams & Bargh, 2008).

- Social exclusion can literally feel cold. After being given the cold shoulder by others in an experiment, people judge the room as colder than do those who were treated warmly (Zhong & Leonardelli, 2008).

- Political expressions may mimic body positions. When leaning to the left—by sitting in a left- rather than right-leaning chair, or squeezing a handgrip with their left hand, or using a mouse with their left hand—people lean more toward the left in their expressed political attitudes (Oppenheimer & Trail, 2010).

In a few rare individuals, the brain circuits for two or more senses become joined in a condition called synesthesia. In these cases, one sort of sensation (such as hearing sound) produces another (such as seeing color). Thus, hearing music may activate color-sensitive cortex regions, triggering a sensation of color (Brang et al., 2008; Hubbard et al., 2005). Seeing the number 3 may evoke a taste sensation (Ward, 2003).

Sensation and cognition, as we have seen, are the two streams that feed the river of perception. If perception is the product of these two sources, what can we say about extrasensory perception, which claims that perception can occur apart from sensory input? For more on that question, see Thinking Critically About: ESP—Perception Without Sensation?

Most of us will never know what it is like to see colorful music, to feel pressure but never pain, or to be unable to recognize the faces of friends and family. But within our ordinary sensation and perception lies much that is truly extraordinary. More than a century of research has revealed many of the secrets of sensation and perception, yet for future generations of researchers, there remain profound and genuine mysteries to solve.

ESP—Perception Without Sensation?

THINKING CRITICALLY ABOUT

5-22 How do ESP claims hold up when put to the test by scientists?

Without sensory input, are we capable of extrasensory perception (ESP)? Nearly half of Americans believe we are (AP, 2007; Moore, 2005).

Are there indeed people—any people—who can read minds, see through walls, or correctly predict the future? Before we evaluate claims of ESP, let’s review them. The most testable and, for this chapter, most relevant ESP claims are

- telepathy: mind-to-mind communication.

- clairvoyance: perceiving remote events, such as a house on fire in another state.

- precognition: perceiving future events, such as an unexpected death in the next month.

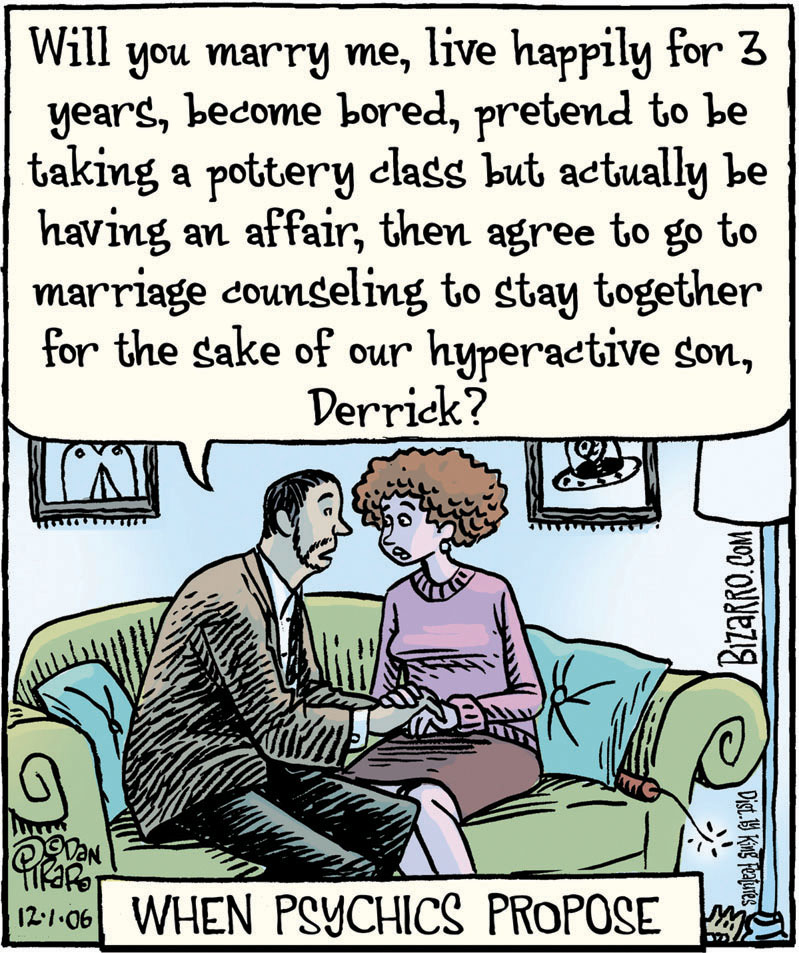

Closely linked with these are claims of psychokinesis, or “mind over matter,” such as using mind power alone to raise a table or affect the roll of a die. (The claim is illustrated by the wry request, “Will all those who believe in psychokinesis please raise my hand?”)

Facts or Fantasies?

Most research psychologists and scientists—including 96 percent of the scientists in one U.S. National Academy of Sciences survey—are skeptical of ESP claims (McConnell, 1991). No greedy—or charitable—psychic has been able to choose the winning lottery jackpot ticket, or make billions on the stock market. In 30 years, unusual predictions have almost never come true, and psychics have virtually never anticipated any of the year’s headline events (Emery, 2004, 2006). The new-century psychics failed to anticipate the big-news events such as the horror of 9/11. (Where were the psychics on 9/10 when we needed them?)

162

What about the hundreds of visions offered by psychics working with the police? When asked, 65 percent of the police departments of America’s 50 largest cities said they had never used psychics (Sweat & Durm, 1993). Of those that had, not one had found them helpful. Psychics’ police work has been no more accurate than guesses made by others (Nickell, 1994, 2005; Reiser, 1982).

Are everyday people’s “visions” any more accurate? Do our dreams predict the future, or do they only seem to do so when we recall or reconstruct them in light of what has already happened? After aviator Charles Lindbergh’s baby son was kidnapped and murdered in 1932 but before the body was discovered, two psychologists invited people to report their dreams about the child (Murray & Wheeler, 1937). How many replied? 1300. How many accurately saw the child dead? 65. How many also correctly anticipated the body’s location—buried among trees? Only 4. Although this number was surely no better than chance, to those 4 dreamers the accuracy of their apparent prior knowledge must have seemed uncanny.

Given the billions of events in the world each day and given enough days, some stunning coincidences are sure to occur. By one careful estimate, chance alone would predict that more than a thousand times a day someone on Earth will think of another person and then within the next five minutes will learn of that person’s death (Charpak & Broch, 2004). With enough time and people, the improbable becomes inevitable.

Testing ESP

When faced with claims of mind reading or out-of-body travel or communication with the dead, how can we separate bizarre ideas from those that sound strange but are true? At the heart of science is a simple answer: Test them to see if they work. If they do, so much the better for the ideas. If they don’t, so much the better for our skepticism.

How might we test ESP claims in a controlled experiment? An experiment differs from a staged demonstration. In the laboratory, the experimenter controls what the “psychic” sees and hears. On stage, the “psychic” controls what the audience sees and hears.

“A person who talks a lot is sometimes right.”

Spanish proverb

Daryl Bem, a respected social psychologist, once joked that “a psychic is an actor playing the role of a psychic” (1984). Yet this one-time skeptic has reignited hopes for scientific evidence of ESP with nine experiments that seemed to show people anticipating future events (2011). In one, for example, people guessed when an erotic scene would appear on a screen in one of two randomly selected positions. Participants guessed right 53.1 percent of the time, beating 50 percent by a small but statistically significant margin.

Bem’s research survived critical reviews by a top-tier journal. But other critics found the methods “badly flawed” (Alcock, 2011) or the statistical analyses “biased” (Wagenmakers et al., 2011). Still others predicted the results could not be repeated by “independent and skeptical researchers” (Helfand, 2011).

Anticipating such skepticism, Bem has made his computer materials available to anyone who wishes to replicate his studies. Regardless of the outcomes, science has done its work. It has been open to a finding that challenges its own worldview, and follow-up research is now assessing the validity of that finding. And that is how science sifts crazy-sounding ideas, leaving most on the historical waste heap while occasionally surprising us.

One skeptic, magician James Randi, has a long-standing offer of $1 million to be given “to anyone who proves a genuine psychic power under proper observing conditions” (Randi, 1999; Thompson, 2010). French, Australian, and Indian groups have made similar offers of up to 200,000 euros (CFI, 2003). Large as these sums are, the scientific seal of approval would be worth far more. To silence those who say there is no ESP, one need only produce a single person who can demonstrate a single, reproducible ESP event. (To silence those who say pigs can’t talk would take but one talking pig.) So far, no such person has emerged.

RETRIEVE + REMEMBER

Question 5.19

If an ESP event occurred under controlled conditions, what would be the next best step to confirm that ESP really exists?

The ESP event would need to be reproduced in other scientific studies.

163