10.2 Stress Effects and Health

LOQ 10-

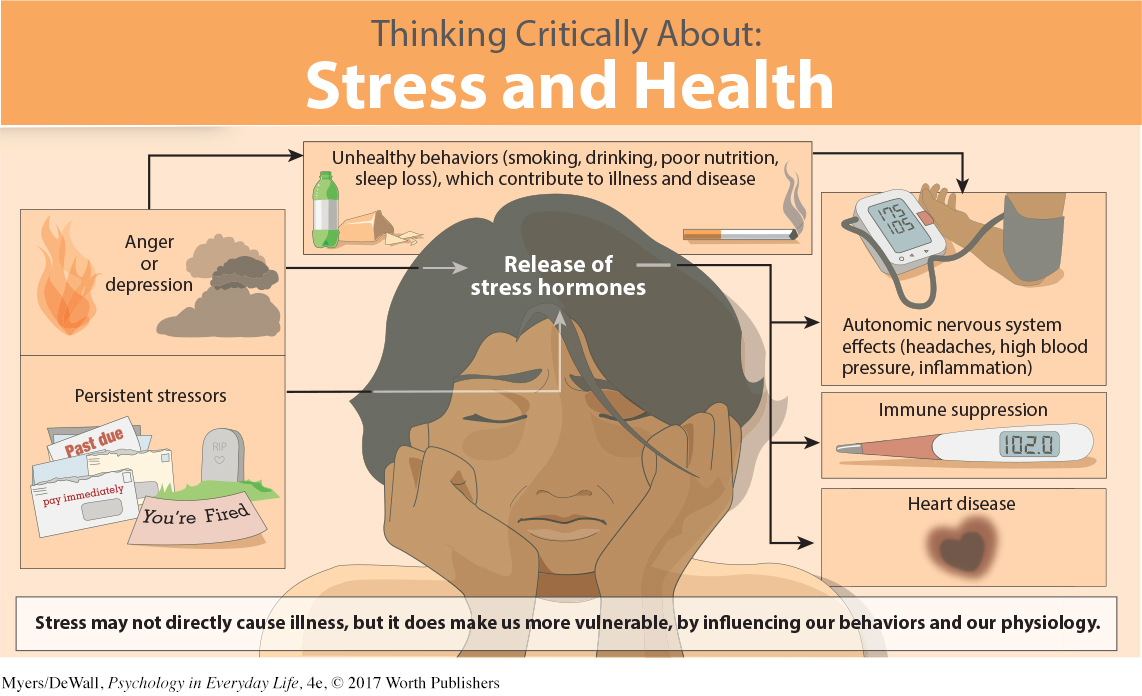

How do you try to stay healthy? Avoid sneezers? Get extra rest? Wash your hands? You should add stress management to that list. Why? Because, as we have seen throughout this text, everything psychological is also biological. Stress is no exception. Stress contributes to high blood pressure and headaches. Stress also leaves us less able to fight off disease. To manage stress, we need to understand these connections.

psychoneuroimmunology the study of how psychological, neural, and endocrine processes combine to affect our immune system and health.

The field of psychoneuroimmunology studies our mind-

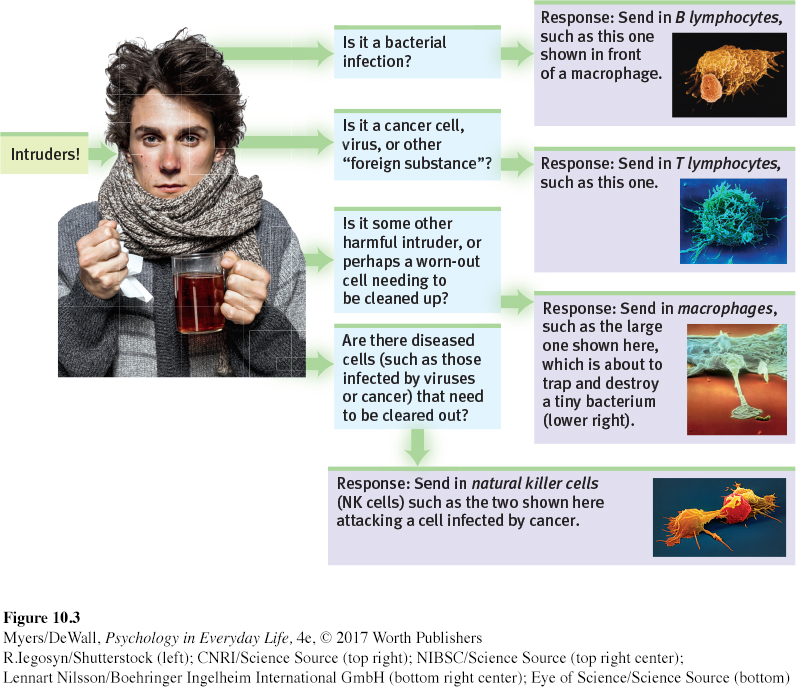

Your immune system resembles a complex security system. When it functions properly, it keeps you healthy by capturing and destroying bacteria, viruses, and other invaders. Four types of cells carry out these search-

B lymphocytes release antibodies that fight bacterial infections.

T lymphocytes attack cancer cells, viruses, and foreign substances—

even “good” ones, such as transplanted organs. Macrophage (“big eater”) cells identify, trap, and destroy harmful invaders and worn-

out cells. Natural killer cells (NK cells) attack diseased cells (such as those infected by viruses or cancer).

Your age, nutrition, genetics, body temperature, and stress all influence your immune system’s activity. When your immune system doesn’t function properly, it can err in two directions:

Responding too strongly, it may attack the body’s own tissues, causing some forms of arthritis or an allergic reaction. Women have stronger immune systems than men do, making them less likely to get infections. But this very strength also puts women at higher risk for self-

attacking diseases, such as lupus and multiple sclerosis (Nussinovitch & Schoenfeld, 2012; Schwartzman- Morris & Putterman, 2012). Underreacting, the immune system may allow a bacterial infection to flare, a dormant herpes virus to erupt, or cancer cells to multiply. Surgeons may deliberately suppress a patient’s immune system to protect transplanted organs (which the body treats as foreign invaders).

289

A flood of stress hormones can also suppress the immune system. In laboratories, immune suppression appears when animals are stressed by physical restraints, unavoidable electric shocks, noise, crowding, cold water, social defeat, or separation from their mothers (Maier et al., 1994). In one such study, monkeys were housed with new roommates—

Human immune systems react similarly. Three examples:

Surgical wounds heal more slowly in stressed people. In one experiment, two groups of dental students received punch wounds (small holes punched in the skin). Punch-

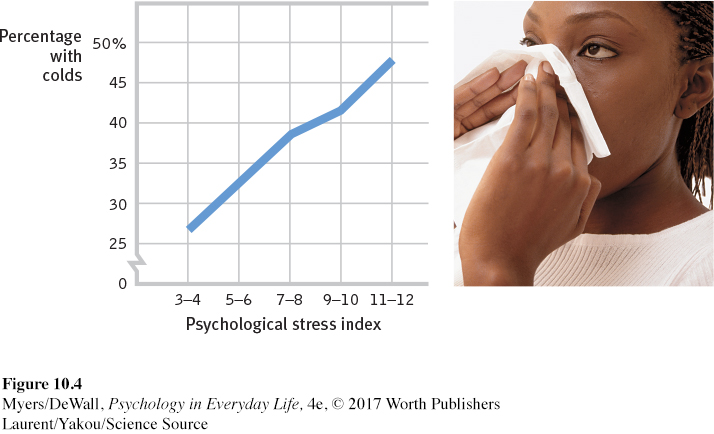

wound healing was 40 percent slower in the group wounded three days before a major exam than in the group wounded during summer vacation (Kiecolt- Glaser et al., 1998). Stressed people develop colds more readily. Researchers dropped a cold virus in the noses of people with high and low life-

stress scores (FIGURE 10.4). Among those living stress- filled lives, 47 percent developed colds. Among those living relatively free of stress, only 27 percent did (Cohen et al., 2003, 2006; Cohen & Pressman, 2006).  Figure 10.4: FIGURE 10.4 Stress and colds People with the highest life stress scores were also most vulnerable when exposed to an experimentally delivered cold virus (Cohen et al., 1991).Laurent/Yakou/Science Source

Figure 10.4: FIGURE 10.4 Stress and colds People with the highest life stress scores were also most vulnerable when exposed to an experimentally delivered cold virus (Cohen et al., 1991).Laurent/Yakou/Science SourceVaccines are less effective with stress. Nurses gave older adults a flu vaccine and then measured how well their bodies fought off bacteria and viruses. The vaccine was most effective among those who experienced low stress (Segerstrom et al., 2012).

290

The stress effect on immunity makes sense. It takes energy to track down invaders, produce swelling, and maintain fevers (Maier et al., 1994). Stress hormones drain this energy away from the disease-

The bottom line: Stress does not make us sick. But it does reduce our immune system’s ability to function, and that leaves us less able to fight infection.

Let’s look now at how stress might affect AIDS, cancer, and heart disease.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 10.2

•________ focuses on mind-

ANSWER: Psychoneuroimmunology

Question 10.3

•What general effect does stress have on our health?

ANSWER: Stress tends to reduce our immune system’s ability to function properly. So, those who regularly experience higher stress also have a higher risk of physical illness.

Stress and AIDS

We know that stress suppresses immune system functioning. What does this mean for people suffering from AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome)? People with AIDS already have a damaged immune system. The name of the virus that triggers AIDS tells us that. “HIV” stands for human immunodeficiency virus.

Stress can’t give people AIDS. But could stress and negative emotions speed the transition from HIV infection to AIDS in someone already infected? Might stress predict a faster decline in those with AIDS? An analysis of 33,252 participants from around the world suggests the answer to both questions is Yes (Chida & Vedhara, 2009). The greater the stress that HIV-

Could reducing stress help control AIDS? The answer again appears to be Yes. Although drug treatments are more effective, educational programs, grief support groups, talk therapy, relaxation training, and exercise programs that reduce distress have all had good results for HIV-

Stress and Cancer

Stress does not create cancer cells. But in a healthy, functioning immune system, lymphocytes, macrophages, and NK cells search out and destroy cancer cells and cancer-

“I didn’t give myself cancer.”

Mayor Barbara Boggs Sigmund (1939–

Does this stress-

There is a danger in overstating the link between attitudes and cancer. Can you imagine how a woman dying of breast cancer might react to a report on the effects of stress on the speed of decline in cancer patients? She could wrongly blame herself for her illness. (“If only I had been more expressive, relaxed, and hopeful.”) Her loved ones could become haunted by the notion that they caused her illness. (“If only I had been less stressful for my mom.”)

For a 7-

For a 7-

It’s important enough to repeat: Stress does not create cancer cells. At worst, stress may affect their growth by weakening the body’s natural defenses against multiplying cancer cells (Lutgendorf et al., 2008; Nausheen et al., 2010; Sood et al., 2010). Although a relaxed, hopeful state may enhance these defenses, we should be aware of the thin line that divides science from wishful thinking. The powerful biological processes at work in advanced cancer or AIDS are not likely to be completely derailed by avoiding stress or maintaining a relaxed but determined spirit (Anderson, 2002; Kessler et al., 1991).

Stress and Heart Disease

LOQ 10-

Depart from reality for a moment. In this new world, you wake up each day, eat your breakfast, and check the news. Among the headlines, you see that four 747 jumbo jet airplanes crashed again yesterday, killing another 1642 passengers. You finish your breakfast, grab your bag, and head out the door. It’s just an average day.

291

coronary heart disease the clogging of the vessels that nourish the heart muscle; the leading cause of death in the United States and many other countries.

Replace airplane crashes with coronary heart disease, the United States’ leading cause of death, and you have re-

Stress and personality also play a big role in heart disease. The more psychological trauma people experience, the more their bodies generate inflammation, which is associated with heart and other health problems, as well as depression (Haapakoski et al., 2015; O’Donovan et al., 2012). Plucking a hair and measuring its level of cortisol (a stress hormone) can help indicate whether a child has experienced prolonged stress or predict whether an adult will have a future heart attack (Karlén et al., 2015; Pereg et al., 2011; Vliegenthart et al., 2016).

The Effects of Personality Type

In a classic study, Meyer Friedman, Ray Rosenman, and their colleagues measured the blood cholesterol level and clotting speed of 40 U.S. male tax accountants during unstressful and stressful times of year (Friedman & Ulmer, 1984). From January through March, the accountants showed normal results. But as the accountants began scrambling to finish their clients’ tax returns before the April 15 filing deadline, their cholesterol and clotting measures rose to dangerous levels. In May and June, with the deadline passed, their health measures returned to normal. Stress predicted heart attack risk for the accountants, with rates going up during their most stressful times. Blood pressure also rises as students approach stressful exams (Conley & Lehman, 2012).

Type A Friedman and Rosenman’s term for competitive, hard-

Type B Friedman and Rosenman’s term for easygoing, relaxed people.

So, are some of us at high risk of stress-

Nine years later, 257 men in the study had suffered heart attacks, and 69 percent of them were Type A. Moreover, not one of the “pure” Type Bs—

As often happens in science, this exciting discovery provoked enormous public interest. But after that initial honeymoon period, researchers wanted to know more. Was the finding reliable? If so, what exactly is so toxic about the Type A profile: Time-

“The fire you kindle for your enemy often burns you more than him.”

Chinese proverb

Hundreds of other studies of young and middle-

In recent years, another personality type has interested stress and heart disease researchers. Type A individuals direct their negative emotion toward dominating others. People with another personality type—

The Effects of Pessimism and Depression

292

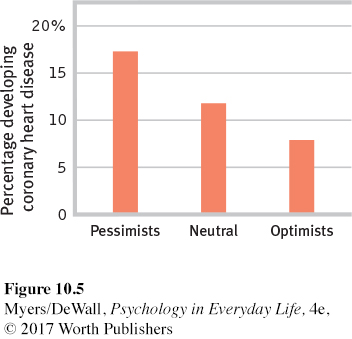

Pessimism, the tendency to judge a glass as half empty instead of half full, increases the risk for heart attack. One U.S. longitudinal study of 1306 men (ages 40 to 90) measured pessimism levels. Those who reported higher levels of pessimism were twice as likely to experience a fatal or nonfatal heart attack ten years later (Kubzansky et al., 2001) (FIGURE 10.5).

Depression, too, can be lethal, as the evidence from many studies has shown (Wulsin et al., 1999). Three examples:

Nearly 4000 English adults (ages 52 to 79) provided mood reports from a single day. Compared with those in a good mood on that day, those in a blue mood were twice as likely to be dead five years later (Steptoe & Wardle, 2011).

In a U.S. survey of 164,102 adults, those who had experienced a heart attack were twice as likely to report also having been depressed at some point in their lives (Witters & Wood, 2015).

People with high scores for depression in the years following a heart attack were four times more likely than their low-

scoring counterparts to develop further heart problems (Frasure- Smith & Lesperance, 2005).

It is still unclear why depression poses such a serious risk for heart disease, but this much seems clear: Depression is disheartening.

To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

To consider how researchers have studied these issues, visit LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know If Stress Increases Risk of Disease?

* * *

In many ways stress can affect our health. (See Thinking Critically About: Stress and Health.) Our stress-

LOQ 10-