10.5 Happiness

LOQ 10-

In The How of Happiness, psychologist Sonja Lyubomirsky (2008) tells the true story of Randy. By any measure, Randy lived a hard life. His dad and best friend both died by suicide. Growing up, his mother’s boyfriend treated him poorly. Randy’s first wife was unfaithful, and they divorced. Despite these setbacks, Randy is a happy person whose endless optimism can light up a room. He remarried and enjoys being a stepfather to three boys. His work life is rewarding. Randy says he survived his life stressors by seeing the “silver lining in the cloud.”

resilience the personal strength that helps most people cope with stress and recover from adversity and even trauma.

Overcoming serious challenges, as Randy did, people may feel a stronger sense of self-

Are you a person who makes everyone around you smile and laugh? Have you, like Randy, bounced back from serious challenges and become stronger because of it? Our state of happiness or unhappiness colors our thoughts and our actions. Happy people perceive the world as a safer place. Their eyes are drawn toward emotionally positive information (Raila et al., 2015). They are more decisive and cooperate more easily. They live healthier and more energized and satisfied lives (Boehm et al., 2015; De Neve et al., 2013; Mauss et al., 2011; Stellar et al., 2015). We all get gloomy sometimes. When that happens, life as a whole may seem depressing and meaningless. Let your mood brighten, and your thinking broadens and becomes more playful and creative (Baas et al., 2008; Forgas, 2008; Fredrickson, 2013). Your relationships, your self-

303

This helps explain why college students’ happiness helps predict their life course. In one study, which surveyed thousands of U.S. college students in 1976 and restudied them at age 37, happy students had gone on to earn significantly more money than their less-

feel-

Moreover—

The reverse is also true: Doing good promotes feeling good. One survey of more than 200,000 people in 136 countries found that, pretty much everywhere, people report feeling happier after spending money on others rather than themselves (Aknin et al., 2013; Dunn et al., 2014). Why does doing good feel so good? It strengthens our social relationships (Aknin et al., 2015; Yamaguchi et al., 2015). Some happiness coaches and instructors harness this force by asking their clients to perform a daily “random act of kindness” and to record how it made them feel.

subjective well-

William James was writing about the importance of happiness (“the secret motive for all [we] do”) as early as 1902. With the rise of positive psychology in the twenty-

The Short Life of Emotional Ups and Downs

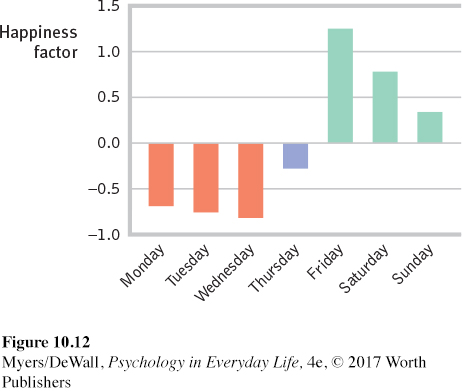

Are some days of the week happier than others? In what may be psychology’s biggest-

304

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

See LaunchPad’s Video: Naturalistic Observation for a helpful tutorial animation about this type of research design.

Over the long run, our emotional ups and downs tend to balance out. This is true even over the course of the day. Positive emotion rises over the early to middle part of most days and then drops off (Kahneman et al., 2004; Watson, 2000). So, too, with day-

Grief over the loss of a loved one or anxiety after a severe trauma can linger. But usually, even tragedy is not permanently depressing. People who have become blind or paralyzed may not completely recover their previous well-

Wealth and Well-

Would you be happier if you made more money? In a 2006 Gallup poll, 73 percent of Americans thought they would be. How important is “Being very well off financially”? “Very important” or “essential,” say 82 percent of entering U.S. college students (Eagen et al., 2016).

305

Money does buy happiness, up to a point. Having enough money to buy your way out of hunger and to enable a sense of control over your life predicts greater happiness (Fischer & Boer, 2011). Money’s power to buy happiness also depends on your current income. A $1000 annual wage increase would do a lot more for the average person in a very poor country than for the average person in a very rich one. But once one has enough money for comfort and security, piling up more and more matters less and less.

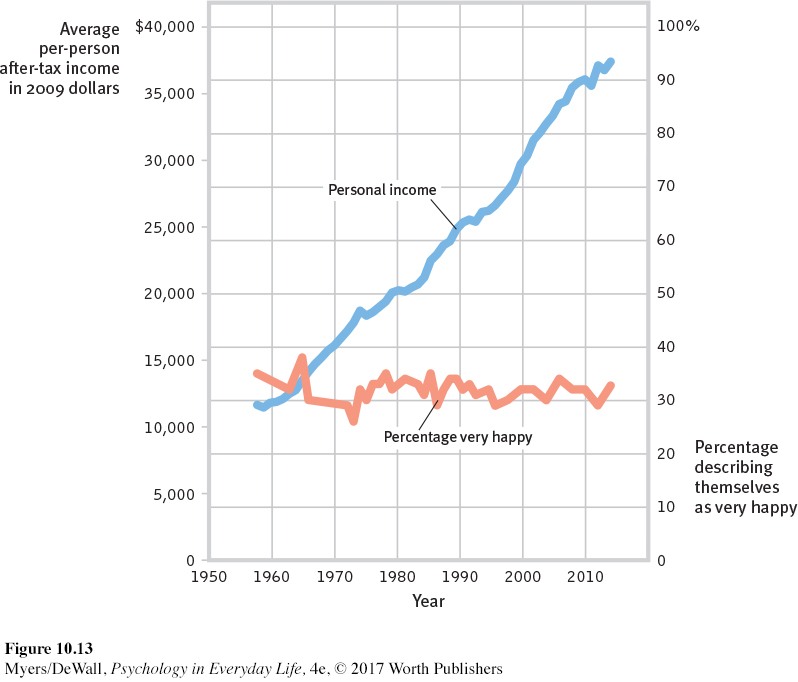

Consider: During the last four decades, the average U.S. citizen’s buying power almost tripled—

Why Can’t Money Buy More Happiness?

Why is it that, for those who are not poor, more and more money does not buy more and more happiness? More generally, why do our emotions seem to be attached to elastic bands that pull us back from highs or lows? Psychology has proposed two answers. Each suggests that happiness is relative.

My Happiness Is Relative to My Own Experience

306

adaptation-

We tend to judge new events by comparing them with our past experiences. Psychologists call this the adaptation-

So, could we ever create a permanent social paradise? Probably not (Campbell, 1975; Di Tella et al., 2010). People who have experienced a recent windfall—

The point to remember: Feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, success and failure are judgments we make about ourselves, based partly on our prior experience (Rutledge et al., 2014).

HI & LOIS

My Happiness Is Relative to Your Success

relative deprivation the perception that we are worse off relative to those with whom we compare ourselves.

For a 6.5-

For a 6.5-

We are always comparing ourselves with others. And whether we feel good or bad depends on our perception of just how successful those others are (Lyubomirsky, 2001). We are slow-

When expectations soar above achievements, we feel disappointed. Thus, the middle-

Just as comparing ourselves with those who are better off creates envy, so counting our blessings as we compare ourselves with those worse off boosts our contentment. In one study, university women considered others’ suffering (Dermer et al., 1979). They viewed vivid images of how grim city life could be in 1900. They imagined and then wrote about various personal tragedies, such as being burned and disfigured. Later, the women expressed greater satisfaction with their own lives. Similarly, when mildly depressed people have read about someone who was even more depressed, they felt somewhat better (Gibbons, 1986). “I cried because I had no shoes,” states a Persian saying, “until I met a man who had no feet.”

Predictors of Happiness

Happy people share many characteristics (TABLE 10.1). But what makes one person so filled with joy, day after day, and others so gloomy? Here, as in so many other areas, the answer is found in the interplay between nature and nurture.

| Researchers Have Found That Happy People Tend to | However, Happiness Seems Not Much Related to Other Factors, Such as |

|---|---|

| Have high self- |

Age. |

| Be optimistic, outgoing, and agreeable. | Gender (women are more often depressed, but also more often joyful). |

| Have close, positive, and lasting relationships. | Physical attractiveness. |

| Have work and leisure that engage their skills. | |

| Have an active religious faith (especially in more religious cultures). | |

| Sleep well and exercise. |

Sources: DeNeve & Cooper, 1998; Diener et al., 2003, 2011; Headey et al., 2010; Lucas et al., 2004; Myers, 1993, 2000; Myers & Diener, 1995, 1996; Steel et al., 2008. Veenhoven (2014) offers a database of 13,000+ correlates of happiness at WorldDatabaseofHappiness.eur.nl.

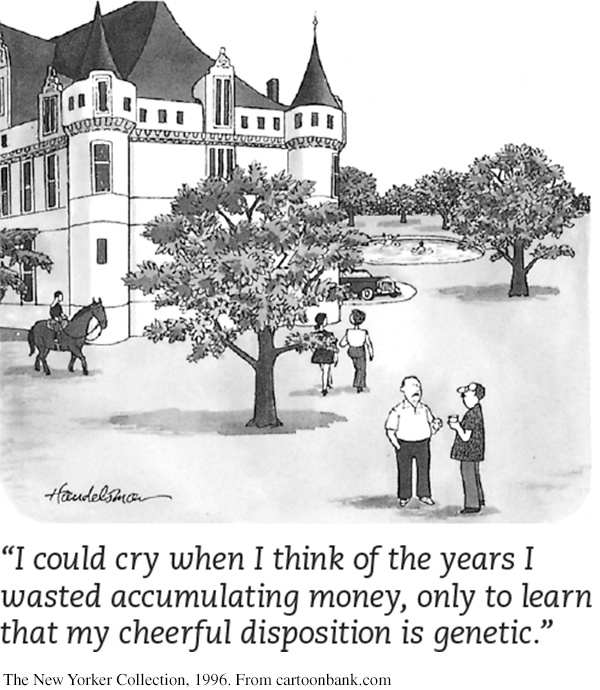

Genes matter. Studies of hundreds of identical and fraternal twins indicate that heredity accounts for about 50 percent of the difference among people’s happiness ratings (Gigantesco et al., 2011; Lykken & Tellegen, 1996). Identical twins raised apart are often similarly happy.

But our personal history and our culture matter, too. On the personal level, as we saw earlier, our emotions tend to balance around a level defined by our experiences. On the cultural level, groups vary in the traits they value. Self-

307

Depending on our genes, our outlook, and our recent experiences, our happiness seems to vary around our “happiness set point.” Some of us seem to be ever upbeat; others, more negative. Even so, our satisfaction with life can change (Lucas & Donnellan, 2007). As researchers studying human strengths will tell you, happiness rises and falls, and we can control some of the factors that make us more or less happy (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

If we can enhance our happiness on an individual level, could we use happiness research to refocus our national priorities? Many psychologists believe we could. Many political leaders agree: 43 nations have begun measuring their citizens’ well-

Scientifically Proven Ways to Have a Happier Life

Your happiness, like your cholesterol level, is genetically influenced. Yet as cholesterol is also influenced by diet and exercise, so happiness is to some extent under your personal control (Nes, 2010; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Here are 10 research-

Take control of your time. Happy people feel in control of their lives. To master your use of time, set goals and divide them into daily aims. This may be frustrating at first, because we all tend to overestimate how much we will accomplish in any given day. The good news is that we generally underestimate how much we can accomplish in a year, given just a little progress every day.

Act happy. As you saw in Chapter 9, people who have been manipulated into a smiling expression felt better. So put on a happy face. Talk as if you feel positive self-

esteem, are optimistic, and are outgoing. We can often act our way into a happier state of mind. Seek work and leisure that engage your skills. Happy people often are in a zone called flow—absorbed in tasks that challenge but don’t overwhelm them. Passive forms of leisure (watching TV) often provide less flow experience than exercising, socializing, or expressing your musical interests. And frequent small positive experiences make for more lasting happiness than big but rare positive events.

308

RubberBall Selects/Alamy

RubberBall Selects/AlamyBuy shared experiences rather than things. Compared with money spent on stuff, money buys more happiness when spent on experiences that you look forward to, enjoy, remember, and talk about (Carter & Gilovich, 2010; Kumar & Gilovich, 2013). This is especially so for socially shared experiences (Caprariello & Reis, 2013). The shared experience of a family vacation may cost a lot, but, as pundit Art Buchwald said, “The best things in life aren’t things.”

Join the “movement” movement. Aerobic exercise can relieve mild depression and anxiety as it promotes health and energy. Sound minds reside in sound bodies.

Give your body the sleep it wants. Happy people live active lives yet save time for renewing sleep. Many people—

high school and college students, especially— suffer from sleep debt. The result is fatigue, diminished alertness, and gloomy moods. If you sleep now, you’ll smile later. Give priority to close relationships. Confiding is good for soul and body. Those who care deeply about you can help you weather difficult times. Compared with unhappy people, happy people engage in less small talk and more meaningful conversations (Mehl et al., 2010). You can nurture your closest relationships by not taking your loved ones for granted. This means being as kind to them as you are to others, affirming them, playing together, and sharing together.

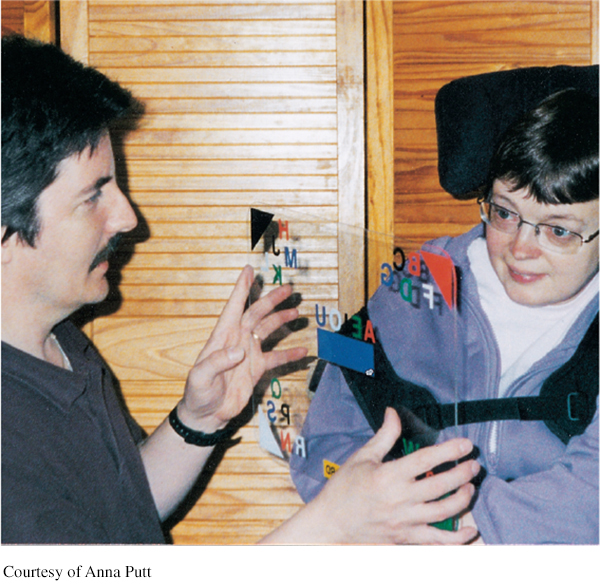

Focus beyond self. Reach out to those in need. Happiness increases helpfulness (those who feel good do good). But doing good also makes us feel good.

Count your blessings and record your gratitude. Keeping a gratitude journal heightens well-

being (Davis et al., 2016). Each day, savor the good moments and positive events and record why they occurred. Express your gratitude to others. Nurture your spiritual self. For many people, faith provides a support community, a reason to focus beyond self, and a sense of purpose and hope. That helps explain why people active in faith communities report greater-

than- average happiness and often cope well with crises.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 10.6

•Which of the following factors does NOT predict self-

Age

Personality traits

Sleep and exercise

Active religious faith

ANSWER: a. Age does NOT effectively predict happiness levels. Better predictors are personality traits, sleep and exercise, and religious faith.