Abraham Maslow’s Self-Actualizing Person

hierarchy of needs Maslow’s pyramid of human needs; at the base are physiological needs. These basic needs must be satisfied before higher-level safety needs, and then psychological needs, become active.

self-actualization according to Maslow, the psychological need that arises after basic physical and psychological needs are met and self-esteem is achieved; the motivation to fulfill our potential.

ABRAHAM MASLOW “Any theory of motivation that is worthy of attention must deal with the highest capacities of the healthy and strong person as well as with the defensive maneuvers of crippled spirits” (Motivation and Personality, 1970, p. 33).

Abraham Maslow proposed that human motivations form a pyramid-shaped hierarchy of needs (Chapter 9). At the base are bodily needs. If those are met, we become concerned with the next-higher level of need, for personal safety. If we feel secure, we then seek to love, to be loved, and to love ourselves. With our love needs satisfied, we seek self-esteem (feelings of self-worth). Having achieved self-esteem, we strive for the top-level needs for self-actualization and self-transcendence. These motives, at the pyramid’s peak, involve reaching our full potential.

Maslow (1970) formed his ideas by studying healthy, creative people rather than troubled clinical cases. His description of self-actualization grew out of his study of people, such as Abraham Lincoln, who had lived rich and productive lives. They were self-aware and self-accepting. They were open and spontaneous. They were loving and caring. They didn’t worry too much about other people’s opinions. Yet they were not self-centered. Curious about the world, they embraced uncertainties and stretched themselves to seek out new experiences (Kashdan, 2009). Once they focused their energies on a particular task, they often regarded that task as their life mission, or “calling” (Hall & Chandler, 2005). Most enjoyed a few deep relationships rather than many shallow ones. Many had been moved by spiritual or personal peak experiences that were beyond normal consciousness.

Maslow considered these to be mature adult qualities. These healthy people had outgrown their mixed feelings toward their parents. They had “acquired enough courage to be unpopular, to be unashamed about being openly virtuous.” Maslow’s work with college students led him to believe that those likely to become self-actualizing adults were likable, caring young people who were “privately affectionate to those of their elders who deserve it,” and “secretly uneasy about the cruelty, meanness, and mob spirit so often found in young people.”

Carl Rogers’ Person-Centered Perspective

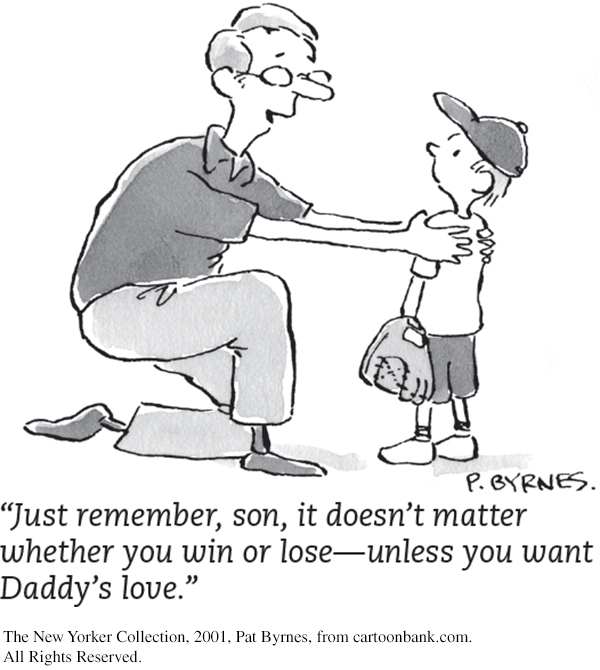

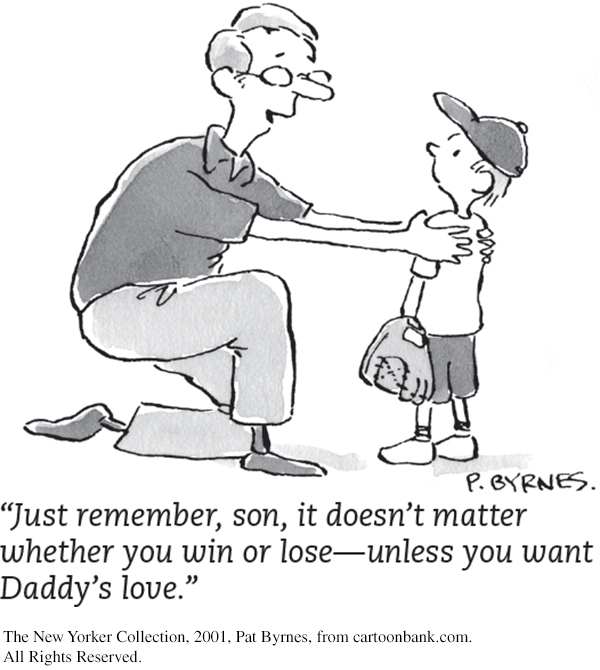

A father not offering unconditional positive regard.

The New Yorker Collection, 2001, Pat Byrnes, from cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

Carl Rogers agreed that people have self-actualizing tendencies. Rogers’ person-centered perspective held that people are basically good. Like plants, we are primed to reach our potential if we are given a growth-promoting environment. People nurture our growth, and we nurture theirs, he said, in three ways (Rogers, 1980).

Being genuine. If we are genuine to another person, we are open with our own feelings. We drop our false fronts and are transparent and self-disclosing.

unconditional positive regard a caring, accepting, nonjudgmental attitude, which Rogers believed would help people develop self-awareness and self-acceptance.

Being accepting. If we are accepting, we offer the other person what Rogers called unconditional positive regard. This is an attitude of total acceptance. We value the person even knowing the person’s failings. We all find it a huge relief to drop our pretenses, confess our worst feelings, and discover that we are still accepted. In a good marriage, a close family, or an intimate friendship, we are free to be ourselves without fearing what others will think.

Being empathic. If we are empathic, we share another’s feelings and reflect that person’s meanings back to them. “Rarely do we listen with real understanding, true empathy,” said Rogers. “Yet listening, of this very special kind, is one of the most potent forces for change that I know.”

Genuineness, acceptance, and empathy are, Rogers believed, the water, sun, and nutrients that enable people to grow like vigorous oak trees. For “as persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude toward themselves” (Rogers, 1980, p. 116). As persons are empathically heard, “it becomes possible for them to listen more accurately to the flow of inner experiencing.”

Rogers called for genuineness, acceptance, and empathy in the relationship between therapist and client. But he also believed that these three qualities nurture growth between any two human beings—between leader and group member, teacher and student, manager and staff member, parent and child, friend and friend.

THE PICTURE OF EMPATHY Being open and sharing confidences is easier when the listener shows real understanding. Within such relationships we can relax and fully express our true selves.

Dylan Martinez/Reuters/Landov

Writer Calvin Trillin (2006) recalls an example of parental genuineness and acceptance at a camp for children with severe disorders, where his wife, Alice, worked. L., a “magical child,” had genetic diseases that meant she had to be tube-fed and could walk only with difficulty. Alice recalled,

One day, when we were playing duck-duck-goose, I was sitting behind her and she asked me to hold her mail for her while she took her turn to be chased around the circle. It took her a while to make the circuit, and I had time to see that on top of the pile [of mail] was a note from her mom. Then I did something truly awful. . . . I simply had to know what this child’s parents could have done to make her so spectacular, to make her the most optimistic, most enthusiastic, most hopeful human being I had ever encountered. I snuck a quick look at the note, and my eyes fell on this sentence: “If God had given us all of the children in the world to choose from, L., we would only have chosen you.” Before L. got back to her place in the circle, I showed the note to Bud, who was sitting next to me. “Quick. Read this,” I whispered. “It’s the secret of life.”

self-transcendence according to Maslow, the striving for identity, meaning, and purpose beyond the self.

self-concept all our thoughts and feelings about ourselves, in answer to the question, “Who am I?”

Maslow and Rogers would have smiled knowingly. For them, a central feature of personality is one’s self-concept—all the thoughts and feelings we have in response to the question, “Who am I?” If our self-concept is positive, we tend to act and perceive the world positively. If it is negative—if in our own eyes we fall far short of our ideal self—we feel dissatisfied and unhappy. A worthwhile goal for therapists, parents, teachers, and friends is therefore to help others know, accept, and be true to themselves, said Rogers.

Assessing the Self

LOQ 12-11 How did humanistic psychologists assess a person’s sense of self?

Humanistic psychologists sometimes assessed personality by asking people to fill out questionnaires that would evaluate their self-concept. One questionnaire, inspired by Carl Rogers, asked people to describe themselves both as they would ideally like to be and as they actually are. When the ideal and the actual self are nearly alike, said Rogers, the self-concept is positive. Assessing his clients’ personal growth during therapy, he looked for closer and closer ratings of actual and ideal selves.

Some humanistic psychologists believed that any standardized assessment of personality, even a questionnaire, is depersonalizing. Rather than forcing the person to respond to narrow categories, these humanistic psychologists presumed that interviews and intimate conversation would provide a better understanding of each person’s unique experiences. Some researchers believe our identity may be revealed using the life story approach—collecting a rich narrative detailing each person’s unique life history (Adler et al., 2016; McAdams & Guo, 2015). A lifetime of stories can show more of a person’s complete identity than can the responses to a few questions.

Evaluating Humanistic Theories

LOQ 12-12 How have humanistic theories influenced psychology? What criticisms have they faced?

Just as Freudian concepts have seeped into modern culture, humanistic psychology has had a far-reaching impact. Maslow’s and Rogers’ ideas have influenced counseling, education, child raising, and management. And they laid the groundwork for today’s scientific positive psychology subfield (Chapter 1).

These theorists have also influenced—sometimes in unintended ways—much of today’s popular psychology. Is a positive self-concept the key to happiness and success? Do acceptance and empathy nurture positive feelings about ourselves? Are people basically good and capable of improving? Many would answer Yes, Yes, and Yes. In 2006, U.S. high school students reported notably higher self-esteem and greater expectations of future career success than did students living in 1975 (Twenge & Campbell, 2008). When you hear talk about the importance of “loving yourself,” you can give some credit to the humanistic theories.

Many psychologists have criticized the humanistic perspective. First, said the critics, its concepts are vague and based on the theorists’ personal opinions, rather than on scientific methods. Consider Maslow’s description of self-actualizing people as open, spontaneous, loving, self-accepting, and productive. Is this a scientific description? Or is it merely a description of Maslow’s own values and ideals, as viewed in his own personal heroes (Smith, 1978)? Imagine another theorist with a different set of heroes, such as the French military conqueror Napoleon and former U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney. This theorist might have described self-actualizing people as “desiring power,” “willing to go to war,” and “self-assured.”

Other critics objected to the attitudes that humanistic psychology encourages. Rogers, for example, said, “The only question which matters is, ‘Am I living in a way which is deeply satisfying to me, and which truly expresses me?’” (quoted by Wallach & Wallach, 1985). Imagine working on a group project with people who refuse to complete any task that is not deeply satisfying or does not truly express their identity. Such attitudes could lead to self-indulgence, selfishness, and a lack of moral restraint (Campbell & Specht, 1985; Wallach & Wallach, 1983).

Humanistic psychologists have replied that a secure, nondefensive self-acceptance is the important first step toward loving others. Indeed, people who recall feeling liked and accepted by a romantic partner—for who they are, not just for their achievements—report being happier in their relationships and acting more kindly toward their partner (Gordon & Chen, 2010).

A final criticism has been that humanistic psychology fails to appreciate our human capacity for evil (May, 1982). Faced with global climate change, overpopulation, terrorism, and the spread of nuclear weapons, we may be paralyzed by either of two ways of thinking. One is a naive optimism that denies the threat (“People are basically good; everything will work out”). The other is a dark despair (“It’s hopeless; why try?”). Action requires enough realism to fuel concern and enough optimism to provide hope. Humanistic psychology, said the critics, encourages the needed hope but not the equally necessary realism about threats.

Retrieve + Remember

Question

12.6

•How did humanistic psychology provide a fresh perspective?

ANSWER: This movement sought to turn psychology’s attention away from drives and conflicts and toward our growth potential. This focus on the way healthy people strive for self-determination and self-realization was in contrast to Freudian theory and strict behaviorism.

Question

12.7

•What does it mean to be empathic? How about self-actualized? Which humanistic psychologists used these terms?

ANSWERS: To be empathic is to share and mirror another person’s feelings. Carl Rogers believed that people nurture growth in others by being empathic. Abraham Maslow proposed that self-actualization is the motivation to fulfill one’s potential, and one of the ultimate psychological needs (the other is self-transcendence).