14.4 The Biomedical Therapies

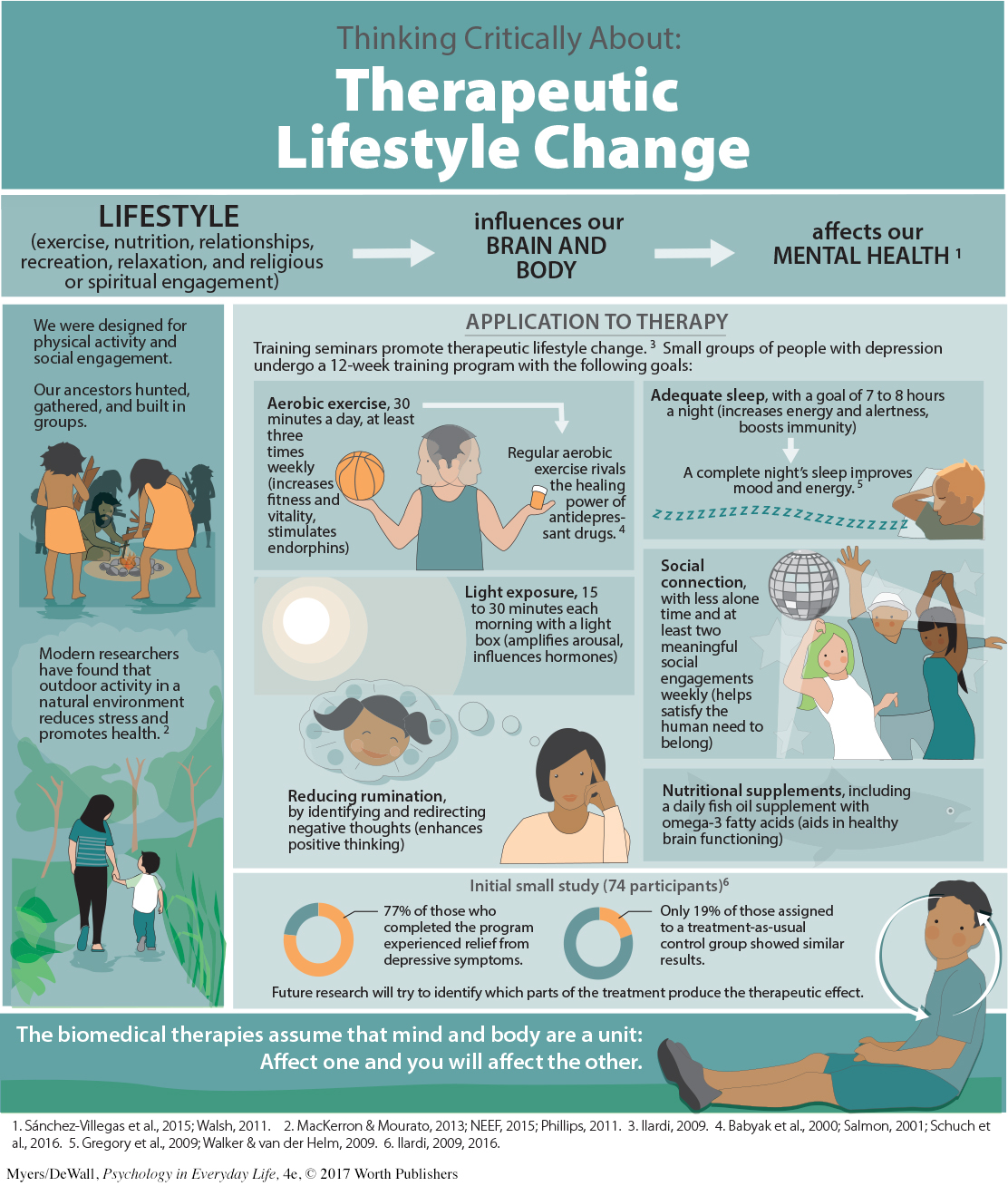

Psychotherapy is one way to treat psychological disorders. The other is biomedical therapy. Biomedical treatments can change the brain’s chemistry with drugs; affect the brain’s circuitry with electrical stimulation, magnetic impulses, or psychosurgery; or influence the brain’s responses with lifestyle changes.

Are you surprised to see lifestyle changes in this list? We find it convenient to talk of separate psychological and biological influences, but everything psychological is also biological. When psychotherapy relieves behaviors associated with obsessive-

The influence is two-

431

LOQ 14-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.12

•What are some examples of lifestyle changes we can make to enhance our mental health?

ANSWER: Exercise regularly, get enough sleep, get more exposure to light (get outside and/or use a light box), nurture important relationships, redirect negative thinking, and eat a diet rich in omega-

Drug Therapies

432

LOQ 14-

By far, the most widely used biomedical treatments today are the drug therapies. Most drugs for anxiety and depression are prescribed by primary care providers, followed by psychiatrists and, in some states, psychologists. Since the 1950s, drug researchers have written a new chapter in the treatment of people with severe disorders. Thanks to drug therapies and support from community mental health programs, today’s resident population of U.S. state and county mental hospitals has dropped to a small fraction of what it was a half-

Almost any new treatment, including drug therapy, is greeted by an initial wave of enthusiasm as many people apparently improve. But that enthusiasm often diminishes on closer examination. To judge the effectiveness of a new treatment, we also need to know:

Do untreated people also improve? If so, how many, and how quickly?

Was recovery due to the drug or to the placebo effect? When patients and/or mental health workers expect positive results, they may see what they expect, not what really happens. Even mere exposure to advertising about a drug’s supposed effectiveness can increase its effect (Kamenica et al., 2013).

To control for these influences when testing a new drug, researchers give half the patients the drug, and the other half a similar-

* * *

The four most common drug treatments for psychological disorders are antipsychotic drugs, antianxiety drugs, antidepressant drugs, and mood-

Antipsychotic Drugs

antipsychotic drugs drugs used to treat schizophrenia and other forms of severe thought disorders.

Accidents sometimes launch revolutions. In this instance, an accidental discovery launched a treatment revolution for people with psychoses. The discovery was that some drugs used for other medical purposes calmed the hallucinations or delusions that are part of these patients’ split from reality. First-

How do antipsychotic drugs work? They mimic certain neurotransmitters. Some block the activity of dopamine by occupying its receptor sites. This finding reinforces the idea that an overactive dopamine system contributes to schizophrenia. Further support for this idea comes from a side effect of another drug. L-

Do antipsychotic drugs also have side effects? Yes, and some are powerful. They may produce sluggishness, tremors, and twitches similar to those of Parkinson’s disease (Kaplan & Saddock, 1989). Long-

Despite their drawbacks, antipsychotics, combined with life-

Antianxiety Drugs

433

antianxiety drugs drugs used to control anxiety and agitation.

Like alcohol, antianxiety drugs, such as Xanax or Ativan, depress central nervous system activity (and so should not be used in combination with alcohol). These drugs are often successfully used in combination with psychological therapy to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-

Some critics fear that antianxiety drugs may reduce symptoms without resolving underlying problems, especially when used as an ongoing treatment. “Popping a Xanax” at the first sign of tension can provide immediate relief, which may reinforce a person’s tendency to take drugs when anxious. Anxiety drugs can also be addictive. Regular users who stop taking these drugs may experience increased anxiety, insomnia, and other withdrawal symptoms.

Antidepressant Drugs

antidepressant drugs drugs used to treat depression, anxiety disorders, obsessive-

The antidepressant drugs were named for their ability to lift people up from a state of depression. These drugs are now also used to treat anxiety disorders, obsessive-

The most commonly prescribed drugs in this group, including Prozac and its cousins Zoloft and Paxil, lift spirits by prolonging the time serotonin molecules remain in the brain’s synapses. They do this by partially blocking the normal reuptake process (see FIGURE 2.4 in Chapter 2). These drugs are called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) because they slow (inhibit) the synaptic vacuuming up (reuptake) of serotonin.

Some professionals prefer the SSRIs over other antidepressants (Jakubovski et al., 2015; Kramer, 2011). SSRIs begin to influence neurotransmission within hours. But their full psychological effect may take four weeks, possibly because these drugs promote the birth of new brain cells (Becker & Wojtowicz, 2007; Jacobs, 2004). Researchers are also exploring the possibility of quicker-

Drugs are not the only way to lift our mood. Aerobic exercise can calm people who feel anxious, energize those who feel depressed, and offer other positive side effects. Cognitive therapy, which helps people reverse their habits of thinking negatively, can boost the drug-

People with depression often improve after a month on antidepressant drugs. But after allowing for natural recovery and the placebo effect, how big is the drug effect? Not big, report some researchers (Kirsch, 2010; Kirsch et al., 2002, 2014; Kirsch & Sapirstein, 1998). In double-

To better understand how clinical researchers have evaluated drug therapies, complete LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know How Well Antidepressants Work?

To better understand how clinical researchers have evaluated drug therapies, complete LaunchPad’s IMMERSIVE LEARNING: How Would You Know How Well Antidepressants Work?

Mood-Stabilizing Medications

In addition to antipsychotic, antianxiety, and antidepressant drugs, psychiatrists have mood-

434

Lithium prevents my seductive but disastrous highs, diminishes my depressions, clears out the wool and webbing from my disordered thinking, slows me down, gentles me out, keeps me from ruining my career and relationships, keeps me out of a hospital, alive, and makes psychotherapy possible.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.13

•How do researchers evaluate the effectiveness of particular drug therapies?

ANSWER: Researchers assign people to treatment and no-

Question 14.14

•The drugs given most often to treat depression are called _______. Schizophrenia is often treated with _______ drugs.

ANSWERS: antidepressants; antipsychotic

Brain Stimulation

LOQ 14-

Electroconvulsive Therapy

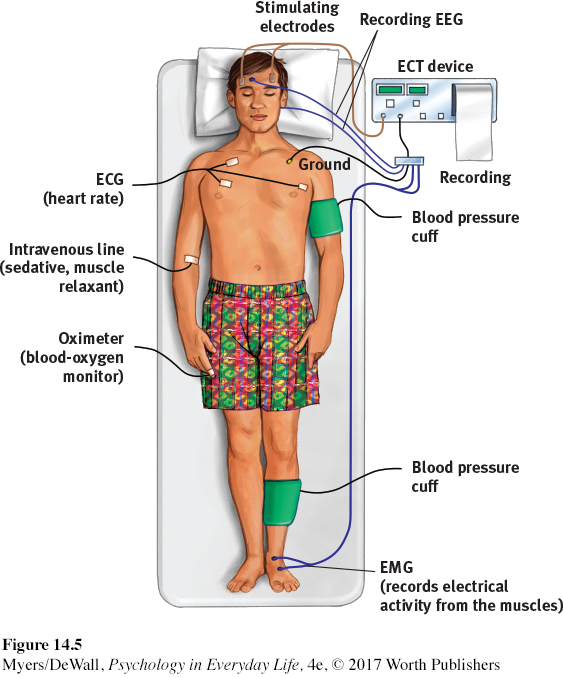

electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) a biomedical therapy for severely depressed patients in which a brief electric current is sent through the brain of an anesthetized patient.

Another biomedical treatment, electro-

Would you agree to ECT for yourself or a loved one? The decision might be difficult, but the treatment works. Surprising as it may seem, study after study confirms that ECT can effectively treat severe depression in patients who have not responded to drug therapy (Bailine et al., 2010; Fink, 2009; Lima et al., 2013; Medda et al., 2015). After three such sessions each week for two to four weeks, 70 percent or more of those receiving ECT improve markedly. They show some memory loss for the treatment period but no apparent brain damage (Bergsholm et al., 1989; Coffey, 1993). Modern ECT causes less memory disruption than earlier versions did (HMHL, 2007). ECT also reduces suicidal thoughts and is credited with saving many from suicide (Kellner et al., 2005). The Journal of the American Medical Association’s conclusion: “The results of ECT in treating severe depression are among the most positive treatment effects in all of medicine” (Glass, 2001).

How does ECT relieve severe depression? After more than 75 years, no one knows for sure. One patient compared ECT to the smallpox vaccine, which was saving lives before we knew how it worked. Perhaps the brief electric current calms neural centers where overactivity produces depression. Some research indicates that ECT works by weakening connections in a “hyperconnected” neural hub in the left frontal lobe (Perrin et al., 2012).

No matter how impressive the results, the idea of electrically shocking a person’s brain still strikes many as barbaric, especially given our ignorance about why ECT works. Moreover, the mood boost may not last long. About 4 in 10 ECT-

435

Nevertheless, in the minds of many psychiatrists and patients, ECT is a lesser evil than severe depression’s misery, anguish, and risk of suicide. As one psychologist reported after ECT relieved his deep depression, “A miracle had happened in two weeks” (Endler, 1982).

Alternative Neurostimulation Therapies

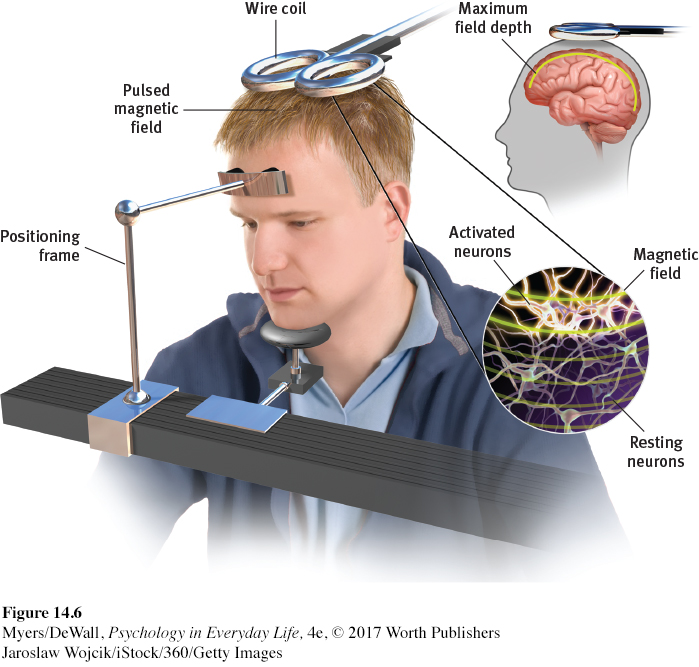

Two other neural stimulation techniques—

repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) the application of repeated pulses of magnetic energy to the brain; used to stimulate or suppress brain activity.

MAGNETIC STIMULATION Depressed moods sometimes improve when repeated pulses surge through a magnetic coil held close to a person’s skull (FIGURE 14.6). The painless procedure—

Initial studies have found a small antidepressant benefit of rTMS (Lepping et al., 2014). How it works is unclear. One possible explanation is that the stimulation energizes the brain’s left frontal lobe, which is relatively inactive during depression (Helmuth, 2001). Repeated stimulation may cause nerve cells to form new functioning circuits through the process of long-

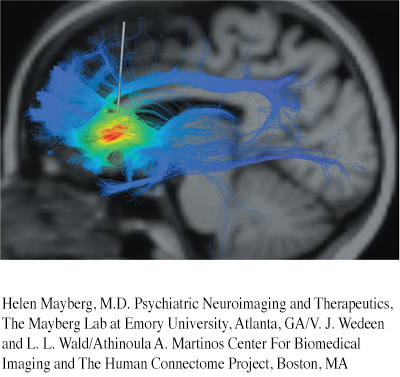

DEEP BRAIN STIMULATION Other patients whose depression has resisted both drugs and ECT have benefited from an experimental treatment pinpointing a brain depression center. Deep brain stimulation manipulates the depressed brain by means of a pacemaker that activates implanted electrodes in brain areas that feed negative emotions and thoughts (Lozano et al., 2008; Mayberg et al., 2005). The stimulation inhibits activity in those brain areas. With deep brain stimulation, some patients have found their depression lifting. Others have become more responsive to drugs or psychotherapy.

436

Deep brain stimulation may also show promise in other treatment areas. Researchers are exploring whether this technique can relieve obsessive-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 14.15

•Severe depression that has not responded to other therapy may be treated with _______ _______, which can cause memory loss for the immediate past. More moderate neural stimulation techniques designed to help alleviate depression include _______ _______ stimulation and _______ magnetic stimulation.

ANSWERS: electroconvulsive therapy (ECT); repetitive transcranial; deep brain

Psychosurgery

psychosurgery surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue in an effort to change behavior.

Psychosurgery is surgery that removes or destroys brain tissue in an attempt to change thoughts and behaviors. Because its effects are irreversible, it is the least-

lobotomy a psychosurgical procedure once used to calm uncontrollably emotional or violent patients. The procedure cut the nerves connecting the frontal lobes to the emotion-

In the 1930s, Portuguese physician Egas Moniz developed what would become the best-

Step 1. Shock the patient into a coma.

Step 2. Hammer an instrument shaped like an icepick through the top of each eye socket. Drive it into the brain.

Step 3. Wiggle the instrument to cut nerves connecting the frontal lobes with the emotion-

controlling centers of the inner brain.

Tens of thousands of severely disturbed people received lobotomies between 1936 and 1954. By that time, some 35,000 people had been lobotomized in the United States alone.

For his work, Moniz received a Nobel Prize (Valenstein, 1986). But today, lobotomies are history. Their intention was simply to disconnect emotion from thought, and indeed, they did usually decrease misery or tension. But their effect was often more drastic, leaving people permanently listless, immature, and uncreative. During the 1950s, when calming drugs became available, psychosurgery became scorned—

Today, more precise micropsychosurgery is sometimes used in extreme cases. For example, if a patient has uncontrollable seizures, surgeons can destroy the specific nerve clusters that cause or transmit the convulsions. MRI-

* * *

TABLE 14.3 summarizes the therapies discussed in this chapter.

| Therapy | Presumed Problem | Therapy Aim | Therapy Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychodynamic | Unconscious conflicts from childhood experiences | Reduce anxiety through self- |

Interpret patients’ memories and feelings. |

| Person- |

Barriers to self- |

Enable growth via unconditional positive regard, genuineness, acceptance, and empathy. | Listen actively and reflect clients’ feelings. |

| Behavior | Dysfunctional behaviors | Learn adaptive behaviors; extinguish problem behaviors | Use classical conditioning (via exposure or aversion therapy) or operant conditioning (as in token economies). |

| Cognitive | Negative, self- |

Promote healthier thinking and self- |

Train people to dispute negative thoughts and attributions. |

| Cognitive- |

Self- |

Promote healthier thinking and adaptive behaviors. | Train people to counter self- |

| Group and family | Stressful relationships | Heal relationships. | Develop an understanding of family and other social systems, explore roles, and improve communication. |

| Therapeutic lifestyle change | Stress and unhealthy lifestyle | Restore healthy biological state. | Alter lifestyle through adequate exercise, sleep, and other changes. |

| Drug therapies | Neurotransmitter malfunction | Control symptoms of psychological disorders. | Alter brain chemistry through drugs. |

| Brain stimulation | Severe, treatment- |

Alleviate depression that is unresponsive to drug therapy. | Stimulate brain through electroconvulsive shock, magnetic impulses, or deep brain stimulation. |

| Psychosurgery | Brain malfunction | Relieve severe disorders. | Remove or destroy brain tissue. |