1.5 Psychology’s Research Ethics

LOQ 1-

We have reflected on how a scientific approach can restrain hidden biases. We have seen how case studies, naturalistic observations, and surveys help us describe behavior. We have noted that correlational studies assess the association between two factors, showing how well one predicts the other. We have examined the logic underlying experiments, which use controls and random assignment to isolate the effects of independent variables on dependent variables.

Hopefully, you are now prepared to understand what lies ahead and to think critically about psychological matters. But before we plunge in, let’s address some common questions about psychology’s ethics and values.

Studying and Protecting Animals

22

Many psychologists study nonhuman animals because they find them fascinating. They want to understand how different species learn, think, and behave. Psychologists also study animals to learn about people. We humans are not like animals; we are animals, sharing a common biology. Animal experiments have therefore led to treatments for human diseases—

Humans are more complex. But the same processes by which we learn are present in rats, monkeys, and even sea slugs. The simplicity of the sea slug’s nervous system is precisely what makes it so revealing of the neural mechanisms of learning.

“Rats are very similar to humans except that they are not stupid enough to purchase lottery tickets.”

Dave Barry, July 2, 2002

Sharing such similarities, should we respect rather than experiment on our animal relatives? The animal protection movement protests the use of animals in psychological, biological, and medical research. Out of this heated debate, two issues emerge.

The basic question: Is it right to place the well-

If we decide to give human life top priority, a second question emerges: What safeguards should protect the well-

Animals have themselves benefited from animal research. After measuring stress hormone levels in samples of millions of dogs brought each year to animal shelters, research psychologists devised handling and stroking methods to reduce stress and ease the dogs’ move to adoptive homes (Tuber et al., 1999). Other studies have helped improve care and management in animals’ natural habitats. By revealing our behavioral kinship with animals and the remarkable intelligence of chimpanzees, gorillas, and other animals, experiments have led to increased empathy and protection for other species. At its best, a psychology concerned for humans and sensitive to animals serves the welfare of both.

Studying and Protecting Humans

What about human participants? Does the image of white-

Occasionally, though, researchers do temporarily stress or deceive people. This happens only when they believe it is unavoidable. Some experiments won’t work if participants know everything beforehand. (Wanting to be helpful, they might try to confirm the researcher’s predictions.)

The APA and Britain’s BPS ethics codes urge researchers to

informed consent giving people enough information about a study to enable them to decide whether they wish to participate.

obtain the participants’ informed consent to participate.

protect participants from out-

of- the- ordinary harm and discomfort. keep information about individual participants confidential.

debriefing after an experiment ends, explaining to participants the study’s purpose and any deceptions researchers used.

fully debrief participants (explain the research afterward).

As noted earlier in relation to nonhuman animals, most universities have ethics committees that screen research proposals and safeguard participants’ well-

Values in Psychology

23

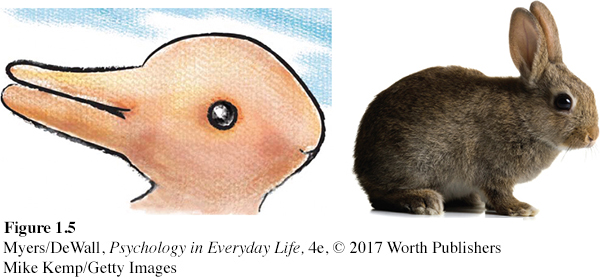

Values affect what we study, how we study it, and how we interpret results. Consider our choice of research topics. Should we study worker productivity or worker morale? Sex discrimination or gender differences? Conformity or independence? Values can also color “the facts”—our observations and interpretations. Sometimes we see what we want or expect to see (FIGURE 1.5).

Even the words we use to describe traits and tendencies can reflect our values. Labels describe and labels evaluate. One person’s rigidity is another’s consistency. One person’s “undocumented worker” is another’s “illegal alien.” One person’s faith is another’s fanaticism. One country’s enhanced interrogation techniques become torture when practiced by an enemy. Our words—

Applied psychology also contains hidden values. If you defer to “professional” guidance—

Others have a different worry about psychology: that it is becoming dangerously powerful. Might psychology, they ask, be used to manipulate people? Knowledge, like all power, can be used for good or evil. Nuclear power has been used to light up cities—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 1.18

•How are animal subjects and human research participants protected?

ANSWER: Animal protection laws, laboratory regulation and inspection, and local and university ethics committees (which screen research proposals) attempt to safeguard animal welfare. International psychological organizations urge researchers to obtain informed consent from human participants, and to protect them from greater-