3.4 Adolescence

88

adolescence the transition period from childhood to adulthood, extending from puberty to independence.

During adolescence we morph from child to adult. Adolescence starts with a physical event—

Physical Development

LOQ 3-

puberty the period of sexual maturation, during which a person becomes capable of reproducing.

Adolescence begins with puberty, the time when we mature sexually. Puberty follows a surge of hormones, which may intensify moods and which trigger a series of bodily changes, outlined in Chapter 4.

Early versus late maturing. Just as in the earlier life stages, we all go through the same sequence of changes in puberty. All girls, for example, develop breast buds and pubic hair before menarche, their first menstrual period. The timing of such changes is less predictable. Some girls start their growth spurt at 9, some boys as late as age 16. How do girls and boys experience early versus late maturation?

For boys, early maturation has mixed effects. Boys who are stronger and more athletic during their early teen years tend to be more popular, self-

The teenage brain. An adolescent’s brain is also a work in progress. This is the time when unused neurons and their connections are pruned (Blakemore, 2008). What we don’t use, we lose.

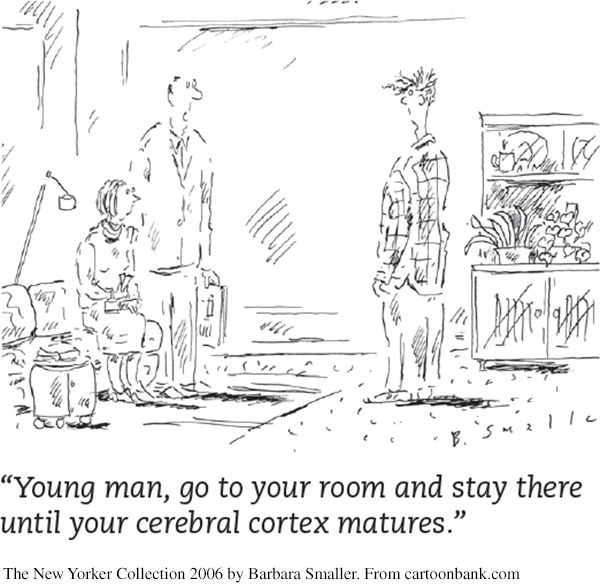

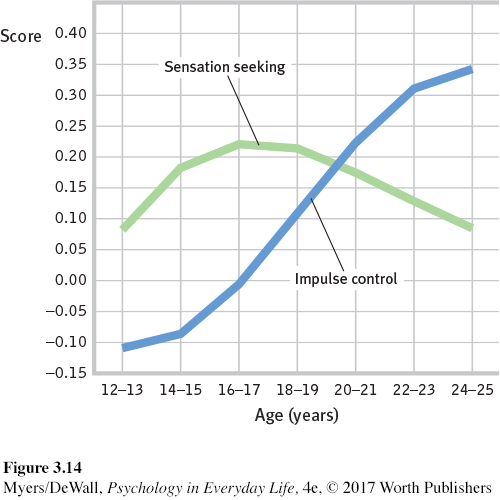

As teens mature, their frontal lobes also continue to develop. But frontal lobe maturation lags behind the development of the emotional limbic system. When puberty’s hormonal surge combines with limbic system development and unfinished frontal lobes, it’s no wonder teens feel stressed. Impulsiveness, risky behaviors, and emotional storms—

“I helped a so-

M. H., Michigan prison inmate, personal correspondence, 2015

89

So, when Junior drives recklessly and academically self-

In 2004, the American Psychological Association (APA) joined seven other medical and mental health associations in filing U.S. Supreme Court briefs arguing against the death penalty for 16-

Cognitive Development

LOQ 3-

During the early teen years, reasoning is often self-

Developing Reasoning Power

When adolescents achieve the intellectual peak Jean Piaget called formal operations, they apply their new abstract thinking tools to the world around them. They may debate human nature, good and evil, truth and justice. Having left behind the concrete images of early childhood, they may search for spirituality and a deeper meaning of life (Boyatzis, 2012; Elkind, 1970). They can now reason logically. They can spot hypocrisy and detect inconsistencies in others’ reasoning (Peterson et al., 1986). (Can you remember having a heated debate with your parents? Did you perhaps even vow silently never to lose sight of your own ideals?)

Developing Morality

90

Two crucial tasks of childhood and adolescence are determining right from wrong and developing character—

MORAL REASONING Piaget (1932) believed that children’s moral judgments build on their cognitive development. Agreeing with Piaget, Lawrence Kohlberg (1981, 1984) sought to describe the development of moral reasoning, the thinking that occurs as we consider right and wrong. Kohlberg posed moral dilemmas—

| Level (approximate age) | Focus | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Preconventional morality (before age 9) | Self- |

“If you save your dying wife, you’ll be a hero.” |

| Conventional morality (early adolescence) | Uphold laws and rules to gain social approval or maintain social order. | “If you steal the drug for her, everyone will think you’re a criminal.” |

| Postconventional morality (adolescence and beyond) | Actions reflect belief in basic rights and self- |

“People have a right to live.” |

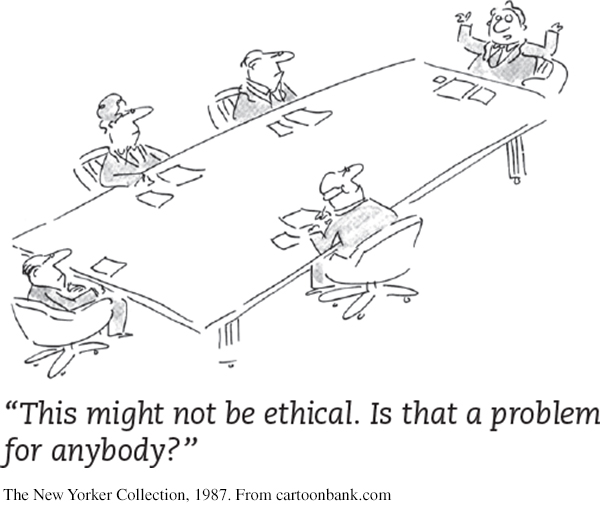

MORAL INTUITION According to psychologist Jonathan Haidt [HITE] (2002, 2006, 2010) much of our morality is rooted in moral intuitions—

This viewpoint on morality finds support in a study of moral decisions. Imagine seeing a runaway trolley headed for five people. All will certainly be killed unless you throw a switch that diverts the trolley onto another track, where it will kill one person. Should you throw the switch? Most say Yes. Kill one, save five.

Now imagine the same dilemma, with one change. This time, your opportunity to save the five requires you to push a large stranger onto the tracks, where he will die as his body stops the trolley. Kill one, save five? The logic is the same, but most say No. Seeking to understand why, researchers used brain imaging to spy on people’s neural responses as they considered such problems (Greene et al., 2001). Despite the identical logic, only the body-

While the new research shows that moral intuitions can beat moral reasoning, other research reaffirms the importance of moral reasoning (Johnson, 2014). The religious and moral reasoning of the Amish, for example, shapes their practices of forgiveness, communal life, and modesty (Narvaez, 2010). Joshua Greene (2010) likens our moral cognition to our phone’s camera. Usually, we rely on the automatic point-

MORAL ACTION Today’s character-

91

These programs also teach the self-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.11

•According to Kohlberg, _________ morality focuses on self-

ANSWERS: preconventional; postconventional; conventional

Question 3.12

•How has Kohlberg’s theory of moral reasoning been criticized?

ANSWER: Kohlberg’s work reflected an individualist worldview, so his theory is less culturally universal than he supposed.

Social Development

LOQ 3-

Erik Erikson (1963) believed that we must resolve a specific crisis at each stage of life. Thus, each stage has its own psychosocial task. Young children wrestle with issues of trust, then autonomy (independence), then initiative. School-

| Stage (approximate age) | Issue | Description of Task |

|---|---|---|

| Infancy (to 1 year) | Trust vs. mistrust | If needs are dependably met, infants develop a sense of basic trust. |

| Toddlerhood (1 to 3 years) | Autonomy vs. shame and doubt | Toddlers learn to exercise their will and do things for themselves, or they doubt their abilities. |

| Preschool (3 to 6 years) | Initiative vs. guilt | Preschoolers learn to initiate tasks and carry out plans, or they feel guilty about their efforts to be independent. |

| Elementary school (6 years to puberty) | Competence vs. inferiority | Children learn the pleasure of applying themselves to tasks, or they feel inferior. |

| Adolescence (teen years into 20s) | Identity vs. role confusion | Teenagers work at refining a sense of self by testing roles and then integrating them to form a single identity, or they become confused about who they are. |

| Young adulthood (20s to early 40s) | Intimacy vs. isolation | Young adults struggle to form close relationships and to gain the capacity for intimate love, or they feel socially isolated. |

| Middle adulthood (40s to 60s) | Generativity vs. stagnation | In middle age, people discover a sense of contributing to the world, usually through family and work, or they may feel a lack of purpose. |

| Late adulthood (late 60s and up) | Integrity vs. despair | Reflecting on their lives, older adults may feel a sense of satisfaction or failure. |

Forming an Identity

identity our sense of self; according to Erikson, the adolescent’s task is to solidify a sense of self by testing and blending various roles.

To refine their sense of identity, adolescents in Western cultures usually try out different “selves” in different situations. They may act out one self at home, another with friends, and still another at school or online. Sometimes these separate worlds overlap. Do you remember having your friend world and family world bump into each other, and wondering, “Which self should I be? Which is the real me?” Most of us make peace with our various selves. In time, we blend them into a stable and comfortable sense of who we are—

92

social identity the “we” aspect of our self-

For both adolescents and adults, our group identities are often formed by how we differ from those around us. When living in Britain, I [DM] become conscious of my Americanness. When spending time in Hong Kong, I [ND] become conscious of my minority White race. When surrounded by women, we are both mindful of our male gender identity. For international students, for those of a minority ethnic group, for gay and transgender people, or for people with a disability, a social identity often forms around their distinctiveness.

But not always. Erikson noticed that some adolescents bypass this period. Some forge their identity early, simply by taking on their parents’ values and expectations. Others may adopt the identity of a particular peer group—

Cultural values may influence teens’ search for an identity. Traditional, more collectivist cultures teach adolescents who they are, rather than encouraging them to decide on their own. In individualist Western cultures, young people may continue to try out possible roles well into their late teen years, when many people begin attending college or working full time. During the early to mid-

intimacy in Erikson’s theory, the ability to form close, loving relationships; a primary developmental task in early adulthood.

For an interactive self-

For an interactive self-

Erikson believed that adolescent identity formation (which continues into adulthood) is followed in young adulthood by a developing capacity for intimacy, the ability to form emotionally close relationships. With a clear and comfortable sense of who you are, said Erikson, you are ready for close relationships. Such relationships are, for most of us, a source of great pleasure.

Parent and Peer Relationships

LOQ 3-

As adolescents in Western cultures seek to form their own identities, they begin to pull away from their parents (Shanahan et al., 2007). The preschooler who can’t be close enough to her mother, who loves to touch and cling to her, becomes the 14-

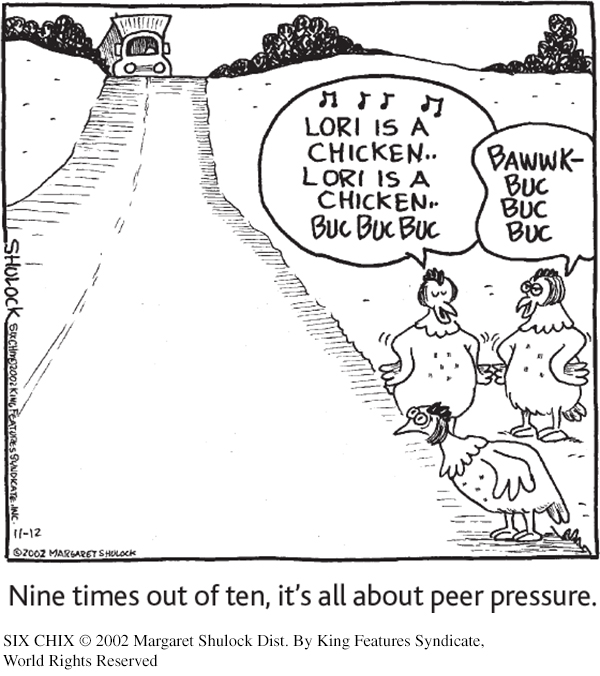

When researchers used a beeper to sample the daily experiences of American teens, they found them unhappiest when alone and happiest when with friends (Csikszentmihalyi &?Hunter, 2003). Teens who start smoking typically have smoker friends who offer cigarettes (J. S. Rose et al., 1999; R. J. Rose et al., 2003). A selection effect partly influences this; those who smoke (or don’t) may select as friends those who also smoke (or don’t). Put two teens together and their brains become supersensitive to reward (Albert et al., 2013). This increased activation helps explain why teens take more driving risks when with friends than they do alone (Chein et al., 2011).

By adolescence, parent-

Positive parent-

As we saw earlier, heredity does much of the heavy lifting in forming individual temperament and personality differences. Parents and peers influence teens’ behaviors and attitudes.

When with peers, teens discount the future and focus more on immediate rewards (O’Brien et al., 2011). Most teens are herd animals. They talk, dress, and act more like their peers than their parents. What their friends are, they often become, and what “everybody’s doing,” they often do. Part of what everybody’s doing is networking—

93

Both online and in real life, for those who feel bullied and excluded by their peers, the pain is acute. Most excluded teens “suffer in silence. . . . A small number act out in violent ways against their classmates” (Aronson, 2001). The pain of exclusion also persists. In one large study, those who were bullied as children showed poorer physical health and greater psychological distress 40 years later (Takizawa et al., 2014)! Peer approval matters.

Teens see their parents as having more influence in other areas—

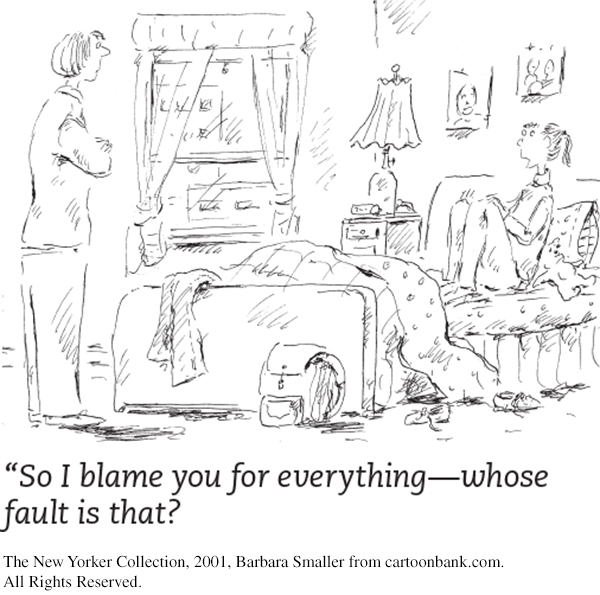

HOW MUCH CREDIT OR BLAME DO PARENTS DESERVE? Parents usually feel enormous satisfaction in their children’s successes, and feel guilt or shame over their failures. They beam over the child who wins an award. They wonder where they went wrong with the child who is repeatedly called into the principal’s office. Freudian psychiatry and psychology have been among the sources of such ideas, by blaming problems from asthma to schizophrenia on “bad mothering.” Society has reinforced parent blaming. Believing that parents shape their offspring as a potter molds clay, people readily praise parents for their children’s virtues and blame them for their children’s vices.

But do parents really damage these future adults by being (take your pick from the toxic-

Parents do matter. The power of parenting is clearest at the extremes: the abused who become abusive, the neglected who become neglectful, the loved but firmly handled children who become self-

Yet in personality measures, shared environmental influences from the womb onward typically account for less than 10 percent of children’s personality differences. In the words of Robert Plomin and Denise Daniels (1987; Plomin, 2011), “Two children in the same family are [apart from their shared genes] as different from one another as are pairs of children selected randomly from the population.” To developmental psychologist Sandra Scarr (1993), this meant that “parents should be given less credit for kids who turn out great and blamed less for kids who don’t.” Knowing that children are not easily sculpted by parental nurture, perhaps parents can relax a bit more and love their children for who they are.

The genetic leash may limit the family environment’s influence on personality, but does it mean that adoptive parenting is a fruitless venture? No. As a new adoptive parent, I [ND] especially find it heartening to know that parents do influence their children’s attitudes, values, manners, politics, and faith (Reifman & Cleveland, 2007). A pair of adopted children or identical twins will, if raised together, have more similar religious beliefs, especially during adolescence (Kelley & De Graaf, 1997; Koenig et al., 2005; Rohan & Zanna, 1996).

Child neglect, abuse, and parental divorce are rare in adoptive homes, in part because adoptive parents are carefully screened. Despite a slightly greater risk of psychological disorder, most adopted children thrive, especially when adopted as infants (Benson et al., 1994; Wierzbicki, 1993). Seven in eight report feeling strongly attached to one or both adoptive parents. As children of self-

94

The investment in raising a child buys many years of joy and love, but also of worry and irritation. Yet for most people who become parents, a child is one’s biological and social legacy—

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.13

•What is the selection effect, and how might it affect a teen’s decision to join sports teams at school?

ANSWER: Adolescents tend to select similar others and to sort themselves into like-

Emerging Adulthood

LOQ 3-

In the Western world, adolescence now roughly equals the teen years. At earlier times, and in other parts of the world today, this slice of life has been much smaller (Baumeister & Tice, 1986). Shortly after sexual maturity, teens would assume adult responsibilities and status. The event might be celebrated with an elaborate initiation—

Where schooling became compulsory, independence was put on hold until after graduation. And as educational goals rose, so did the age of independence. Adolescents are now taking more time to finish college, leave the nest, and establish careers. In 1960, three-

emerging adulthood a period from about age 18 to the mid-

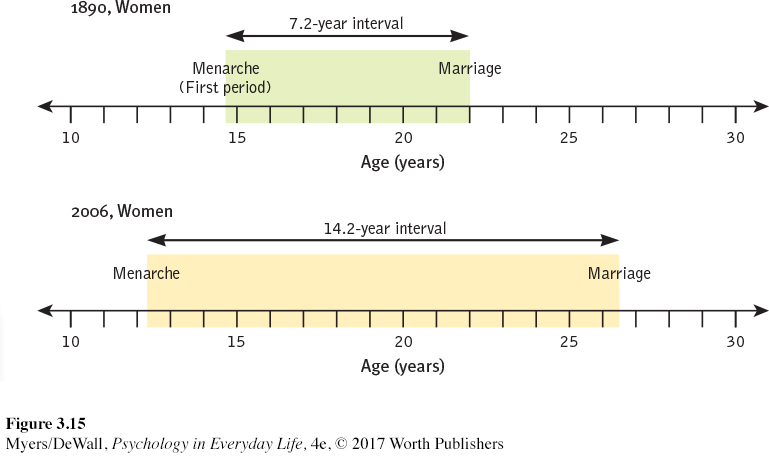

Delayed independence has overlapped with an earlier onset of puberty, widening the once-

95

Retrieve + Remember

Question 3.14

•Match the psychosocial development stage below (1–

Infancy

Toddlerhood

Preschool

Elementary school

Adolescence

Young adulthood

Middle adulthood

Late adulthood

Generativity vs. stagnation

Integrity vs. despair

Initiative vs. guilt

Intimacy vs. isolation

Identity vs. role confusion

Competence vs. inferiority

Trust vs. mistrust

Autonomy vs. shame and doubt

ANSWERS: 1. g, 2. h, 3. c, 4. f, 5. e, 6. d, 7. a, 8. b