4.2 Human Sexuality

116

asexual having no sexual attraction to others.

In a British survey of 18,876 people, 1 percent were seemingly asexual, having “never felt sexually attracted to anyone at all” (Bogaert, 2004, 2006b, 2012, 2015). People identifying as asexual are, however, nearly as likely as others to report masturbating, noting that it feels good, reduces anxiety, or “cleans out the plumbing.”

As you’ve probably noticed, we can hardly talk about gender without talking about our sexuality. For all but the tiny fraction of us considered asexual, dating and mating become a high priority from puberty on. Our sexual feelings and behaviors reflect both physiological and psychological influences.

The Physiology of Sex

Unlike hunger, sex is not an actual need. (Without it, we may feel like dying, but we will not.) Yet sex is a part of life. Had this not been so for all your ancestors, you would not be reading this book. Sexual motivation is nature’s clever way of making people procreate, thus enabling our species’ survival. As the pleasure we take in eating is nature’s method of ensuring we nourish our bodies, so the desires and pleasures of sex are nature’s way of driving us to preserve and spread our genes. Life is sexually transmitted.

Hormones and Sexual Behavior

LOQ 4-

estrogens sex hormones, such as estradiol, that contribute to female sex characteristics and are secreted in greater amounts by females than by males. Estrogen levels peak during ovulation. In nonhuman mammals this promotes sexual receptivity.

Among the forces driving sexual behavior are the sex hormones. As we noted earlier, the main male sex hormone is testosterone. The main female sex hormones are the estrogens, such as estradiol. Sex hormones influence us at many points in the life span:

During the prenatal period, they direct our development as males or females.

During puberty, a sex hormone surge ushers us into adolescence.

After puberty and well into the late adult years, sex hormones facilitate sexual behavior.

In most mammals, sexual interest and fertility overlap. Females become sexually receptive when their estrogen levels peak at ovulation. By injecting female animals with estrogens, researchers can increase their sexual interest. Hormone injections do not affect male animals’ sexual behavior as easily because male hormone levels are more constant (Piekarski et al., 2009). Nevertheless, male hamsters that have had their testosterone-

Hormones do influence human sexuality, but more loosely. Researchers are exploring and debating whether women’s mating preferences change across the menstrual cycle (Gildersleeve et al., 2014; Wood et al., 2014). At ovulation, women’s estrogens surge, as does their testosterone, though not as much. (Recall that women have testosterone, though less than men have.) Some evidence suggests that, among women with mates, sexual desire rises slightly at this time—

More than other mammalian females, women are responsive to their testosterone levels (van Anders, 2012). If a woman’s natural testosterone level drops, as happens with removal of the ovaries or adrenal glands, her sexual interest may plummet (Davison & Davis, 2011; Lindau et al., 2007). But testosterone-

Testosterone-

Large hormonal surges or declines do affect men’s and women’s desire. These shifts take place at two predictable points in the life span, and sometimes at an unpredictable third point:

During puberty, the surge in sex hormones triggers development of sex characteristics and sexual interest. If this hormonal surge is prevented, sex characteristics and sexual desire do not develop normally (Peschel & Peschel, 1987). This happened in Europe during the 1600s and 1700s, when boy sopranos were castrated to preserve their high voices for Italian opera.

In later life, estrogen and testosterone levels fall. Women experience menopause, males a more gradual change (Chapter 3). Sex remains a part of life, but as sex hormone levels decline, sexual fantasies and intercourse decline as well (Leitenberg & Henning, 1995).

For some, surgery or drugs may cause hormonal shifts. After surgical castration, men’s sex drive typically falls as testosterone levels decline sharply (Hucker & Bain, 1990). When male sex offenders took a drug that reduced their testosterone level to that of a boy before puberty, they also lost much of their sexual urge (Bilefsky, 2009; Money et al., 1983).

To recap, we might compare human sex hormones, especially testosterone, to the fuel in a car. Without fuel, a car will not run. But if the fuel level is at least adequate, adding more won’t change how the car runs. This isn’t a perfect comparison, because hormones and sexual motivation influence each other. But it does suggest that biology alone cannot fully explain human sexual behavior. Hormones are the essential fuel for our sex drive. But psychological stimuli turn on the engine, keep it running, and shift it into high gear. Let’s now see just where that drive usually takes us.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.4

•The primary male sex hormone is _______. The primary female sex hormones are the _______.

ANSWERS: testosterone; estrogens

The Sexual Response Cycle

117

LOQ 4-

sexual response cycle the four stages of sexual responding described by Masters and Johnson—

As we noted in Chapter 1, science often begins by carefully observing behavior. Sexual behavior is no exception. In the 1960s, two researchers—

Excitement: The genital areas fill with blood, causing a woman’s clitoris and a man’s penis to swell. A woman’s vagina expands and secretes lubricant. Her breasts and nipples may enlarge.

Plateau: Excitement peaks as breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates continue to rise. A man’s penis becomes fully engorged—

to an average 5.6 inches, among 1661 men who measured themselves for condom fitting (Herbenick et al., 2014). Some fluid— frequently containing enough live sperm to enable conception— may appear at its tip. A woman’s vaginal secretion continues to increase, and her clitoris retracts. Orgasm feels imminent. Orgasm: Muscles contract all over the body. Breathing, pulse, and blood pressure rates continue to climb. Men and women don’t differ much in the delight they receive from sexual release. PET scans have shown that the same brain regions were active in men and women during orgasm (Holstege et al., 2003a,b).

refractory period in human sexuality, a resting pause that occurs after orgasm, during which a man cannot achieve another orgasm.

Resolution: The body gradually returns to its unaroused state as genital blood vessels release their accumulated blood. This happens relatively quickly if orgasm has occurred, relatively slowly otherwise. (It’s like the nasal tickle that goes away rapidly if you have sneezed, slowly otherwise.) Men then enter a refractory period, a resting period that lasts from a few minutes to a day or more. During this time, they cannot achieve another orgasm. Women have a much shorter refractory period, enabling them to have more orgasms if restimulated during or soon after resolution.

As you learned in Chapter 2’s discussion of neural processing, the “refractory period” is also a brief resting pause that occurs after a neuron has fired.

A nonsmoking 50-

Sexual Dysfunctions

sexual dysfunction a problem that consistently impairs sexual arousal or functioning.

erectile disorder inability to develop or maintain an erection due to insufficient bloodflow to the penis.

female orgasmic disorder distress due to infrequently or never experiencing orgasm.

Masters and Johnson had two goals: to describe the human sexual response cycle, and to understand and treat problems that prevent people from completing that cycle. Sexual dysfunctions consistently impair sexual arousal or functioning. Some involve sexual motivation—

Psychological and medical therapies can help people with sexual dysfunctions (Frühauf et al., 2013). Behaviorally oriented therapy, for example, can help men learn ways to control their urge to ejaculate, or help women learn to bring themselves to orgasm. Starting with the introduction of Viagra in 1998, erectile disorder has been routinely treated by taking a pill. Some modestly effective drug treatments for female sexual interest/arousal disorder are also available.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

118

LOQ 4-

Every day, more than 1 million people worldwide acquire a sexually transmitted infection (STI; also called STD, for sexually transmitted disease) (WHO, 2013). “Compared with older adults,” reports the Centers for Disease Control (2016b), “sexually active adolescents aged 15–

To understand the mathematics of infection, imagine this scenario. Over the course of a year, Pat has sex with 9 people. By that time, each of Pat’s partners has had sex with 9 other people, who in turn have had sex with 9 others. How many partners—

Condoms are very effective in blocking the spread of some STIs. The effects were clear when Thailand promoted condom use by commercial sex workers. Over a 4-

AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome) a life-

Condoms offer only limited protection against certain skin-

Half of all humans with HIV (and one-

Just over half of Americans with AIDS are between ages 30 and 49 (CDC, 2013). Given AIDS’ long incubation period, this means that many were infected in their teens and twenties. In 2012, the death of 1.6 million people with AIDS worldwide left behind countless grief-

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.5

•Someone who is distressed by impaired sexual arousal may be diagnosed with a _______ _______.

ANSWER: sexual dysfunction

Question 4.6

•From a biological perspective, HIV is passed more readily from women to men than from men to women. True or false?

ANSWER: False. HIV is transmitted more easily and more often from men to women.

The Psychology of Sex

LOQ 4-

Biological factors powerfully influence our sexual motivation and behavior. But despite our shared biology, human sexual motivation and behavior vary widely—

What motivates people to have sex? The 281 (by one count) expressed reasons have ranged widely—

External Stimuli

Men and women become aroused when they see, hear, or read erotic material (Heiman, 1975; Stockton & Murnen, 1992). In men more than in women, feelings of sexual arousal closely mirror their (more obvious) physical genital responses (Chivers et al., 2010).

People may find sexual arousal either pleasing or disturbing. (Those who wish to control their arousal often limit their exposure to arousing material, just as those wishing to avoid overeating limit their exposure to tempting food cues.) With repeated exposure to any stimulus, including an erotic stimulus, our response lessens—

Can exposure to sexually explicit material have lingering negative effects? Researchers have found that it can, in two areas especially.

Believing rape is acceptable: In some studies, people have viewed scenes in which women were forced to have sex and appeared to enjoy it. Those viewers were more accepting of the false idea that many women want to be overpowered. Male viewers also expressed more willingness to hurt women and to commit rape after viewing these scenes (Allen et al., 1995, 2000; Foubert et al., 2011; Malamuth & Check, 1981; Zillmann, 1989).

119

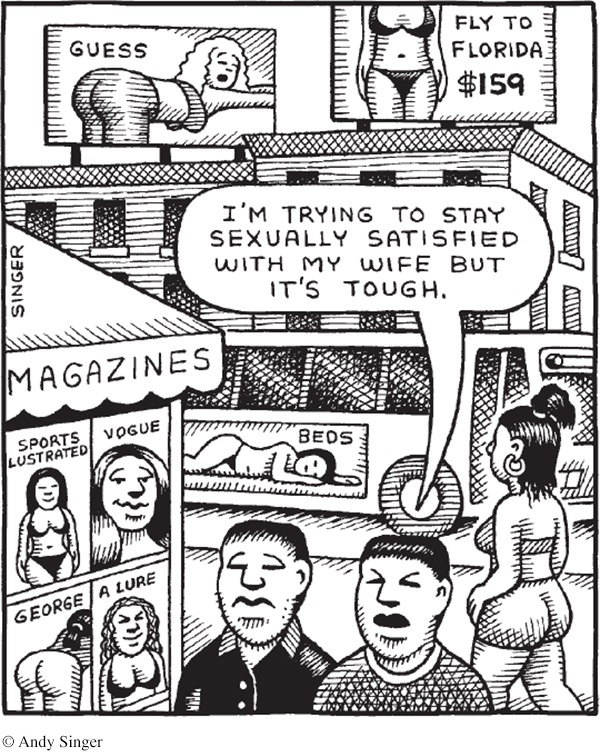

Reducing satisfaction with a partner’s appearance or with a relationship: After viewing images or X-

rated films of sexually attractive women and men, people have judged an average person, their own partner, or their spouse as less attractive. And they have found their own relationship less satisfying (Kenrick & Gutierres, 1980; Kenrick et al., 1989; Lambert et al., 2012; Weaver et al., 1984). Perhaps reading or watching erotica’s unlikely scenarios may create expectations few men and women can fulfill.

Imagined Stimuli

Sexual arousal and desire can also be products of our imagination. People left with no genital sensation after a spinal cord injury can still feel sexual desire, and many engage in sexual intercourse (Donohue & Gebhard, 1995; Sipski et al., 1999; Willmuth, 1987).

Both men and women (about 95 percent of each) report having sexual fantasies, which for a few women can produce orgasms (Komisaruk & Whipple, 2011). Men, regardless of sexual orientation, tend to have more frequent, more physical, and less romantic fantasies (Schmitt et al., 2012). They also prefer less personal and faster-

Does fantasizing about sex indicate a sexual problem or dissatisfaction? No. If anything, sexually active people have more sexual fantasies.

Sexual Risk Taking and Teen Pregnancy

LOQ 4-

Thanks to decreased sexual activity and increased protection, teen pregnancy rates are declining (CDC, 2016b). Yet compared with European teens, American teens have a higher pregnancy rate (Sedgh et al., 2015). What environmental factors contribute to sexual risk taking among teens?

MINIMAL COMMUNICATION ABOUT BIRTH CONTROL Many teens are uncomfortable discussing birth control with parents, partners, and peers. But teens who talk freely and openly with their parents and with their partner in an exclusive relationship are more likely to use contraceptives (Aspy et al., 2007; Milan & Kilmann, 1987).

“Condoms should be used on every conceivable occasion.”

Anonymous

IMPULSIVE SEXUAL BEHAVIOR Among sexually active 12-

ALCOHOL USE Among late teens and young adults, most sexual hook-

social script culturally modeled guide for how to act in various situations.

MASS MEDIA INFLUENCES The more sexual content adolescents and young adults view or read, the more likely they are to perceive their peers as sexually active, to develop sexually permissive attitudes, and to experience early intercourse (Escobar-

120

Media influences can either increase or decrease sexual risk taking. One long-

What are the characteristics of teens who delay having sex?

High intelligence Teens with high rather than average intelligence test scores more often delayed sex, partly because they considered possible negative consequences and were more focused on future achievements than on here-

and- now pleasures (Harden & Mendle, 2011). Religious engagement Actively religious teens, especially young women, often reserve sexual activity for adulthood (Hull et al., 2011; Štulhofer et al., 2011). The most common reason U.S. teens give for not having sex is that it conflicts with their “religion or morals” (Guttmacher Institute, 2012).

Father presence Studies that followed hundreds of New Zealand and U.S. girls from age 5 to 18 found that having Dad around reduces the risk of teen pregnancy. A father’s presence was linked to lower sexual activity before age 16 and to lower teen pregnancy rates (Ellis et al., 2003).

Participation in service learning programs Teens who volunteered as tutors or teachers’ aides, or participated in community projects, have had lower pregnancy rates than other teens randomly assigned to control groups (Kirby, 2002; O’Donnell et al., 2002). Does service learning promote a sense of personal competence, control, and responsibility? Does it encourage more future-

oriented thinking? Or does it simply reduce opportunities for unprotected sex? Researchers don’t have those answers yet.

* * *

In the rest of this chapter, we will consider two special topics: sexual orientation (the direction of our sexual interests), and evolutionary psychology’s explanation of our sexuality.

Retrieve + Remember

Question 4.7

•What factors influence our sexual motivation and behavior?

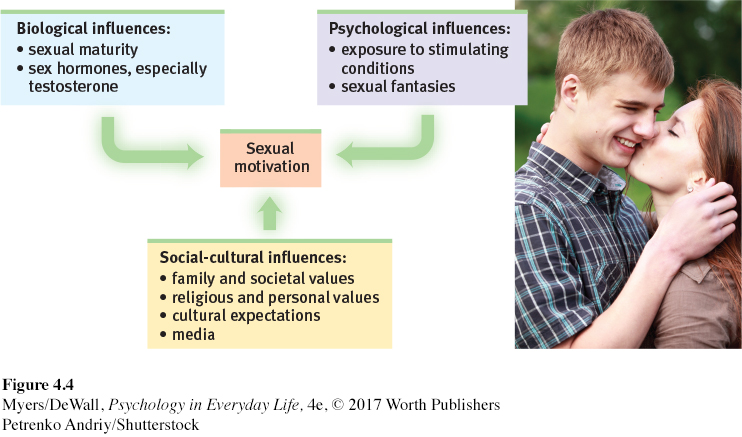

ANSWER: Influences include biological factors such as sexual maturity and sex hormones, psychological factors such as environmental stimuli and fantasies, and social-

Question 4.8

•Which THREE of the following five factors contribute to unplanned teen pregnancies?

Alcohol use

Higher intelligence level

Father absence

Mass media models

Participating in service learning programs

ANSWERS: a, c, d